Hal Chase and the Black Sox Scandal

This article was originally published in the June 2023 edition of the SABR Black Sox Scandal Committee Newsletter.

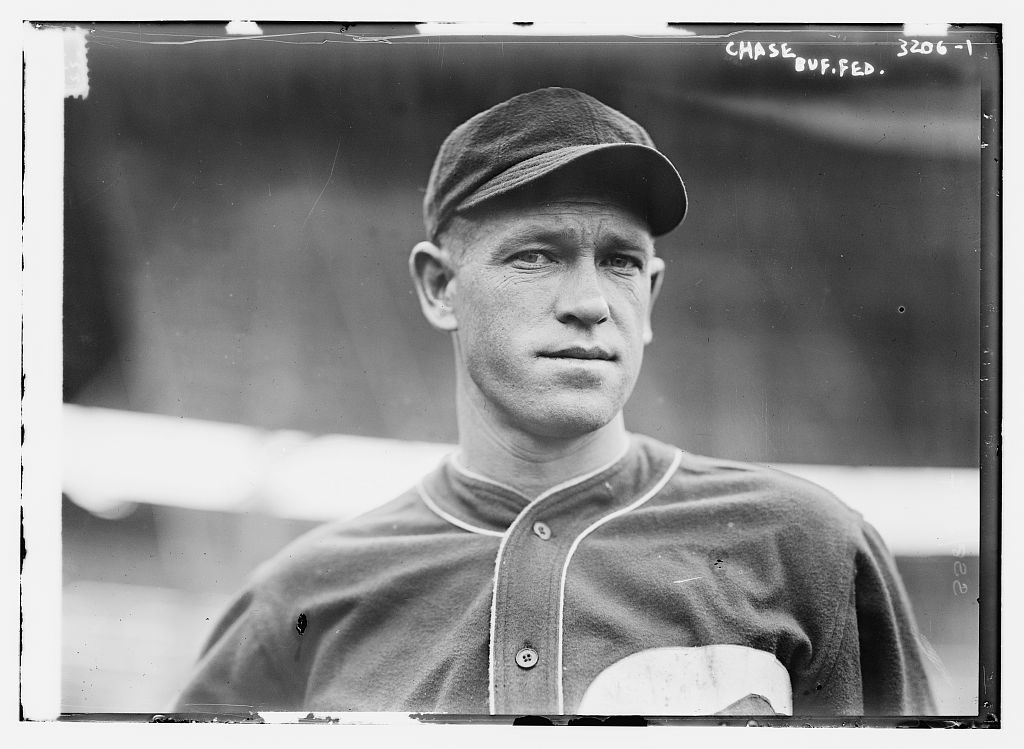

First baseman Hal Chase was implicated in the Black Sox Scandal and the subject of many accusations of game-fixing during his major-league career. But how crucial was his role in the fixing of the 1919 World Series? (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Slick-fielding first baseman Hal Chase has been described as “the most notoriously corrupt player in baseball history.”1 And few game-fixing incidents of the Deadball Era were complete without him.

It was predictable that when the corruption of the 1919 World Series was exposed, Chase was implicated in the affair. In this essay, the extent of Chase’s involvement in the Black Sox Scandal will be examined. Was he an important actor in the Series fix conspiracy or merely a bit player? Or was Chase even less than that, just an in-the-know bettor who cleaned up on advance knowledge that the White Sox were going to dump the Series, as Chase himself claimed?

Superimposed upon the degree of Chase’s participation in the fix is his possible status as scandal role model. In 1918, he was officially exonerated by National League president John Heydler on charges that he had fixed games while playing for the Cincinnati Reds. Did this whitewashing embolden the Black Sox conspirators and prompt their belief that fixing the 1919 World Series was a low risk/high reward proposition?

*****

In 1905, Chase began his 15-season career as a major leaguer playing first base for the New York Highlanders. Although a good, if not exceptional, right-handed batter and an excellent baserunner, it was the left-handed Chase’s fielding that attracted immediate attention. Graceful, athletic, quick thinking, and innovative, “Prince Hal” soon revolutionized the way his position was played. Even decades after his departure from the game, Chase was still being cited as baseball’s finest defensive first baseman by qualified observers (including Babe Ruth.)2

Chase’s psyche was another matter, and one that no essay-length narrative can do adequate justice.3 Charming, charismatic, self-centered, amoral, and utterly corrupt are descriptives that have been applied to him. Doubts about the integrity of Chase’s playing performance surfaced as early as 1908. But in its beginnings, Chase’s “laying down” has been ascribed to pique, hangovers, sulking over being disciplined, or trying to undermine New York managers, particularly George Stallings (1909-1910) and Frank Chance (1913). Although suspicions to the contrary exist, throwing games for money still lay in a young Chase’s future.

Following his trade to the Chicago White Sox in June 1913, Chase predictably jumped to the new Federal League the following year. He performed well, batting a career-high .347 in 75 games for the Buffalo Blues. In 1915, he led the Federal League in home runs (17).

But there was no great rush to sign Chase when the outlaw circuit collapsed over the winter. By now, Chase’s reputation for unreliability, sowing discord among teammates, and suspect on-field performance made him anathema to most American and National League clubs. Eventually, the Cincinnati Reds decided to take a chance on him, and the 33-year-old Chase repaid his new team with an outstanding season, leading the NL in base hits (184) and batting average (.339) in 1916.

Meanwhile, world events pushed the country toward the conflict long raging in Europe. Coinciding with formal American entry into World War I in April 1917 was the incidental effect mobilization had on gambling. Horse racing and boxing, the only sports other than baseball that attracted much wagering activity, were promptly affected. Many, although not all, American racetracks shuttered for the duration while boxing matches were also greatly curtailed.4 In the short run, however, baseball was pretty much unscathed by the war effort, quickly turning major league ballparks into a magnet for professional gamblers. And in short order, long dormant game-fixing returned to major league baseball, largely courtesy of Hal Chase.5

Perhaps in cahoots with gamblers but more likely on his own initiative, the chronically cash-strapped Chase – he was a compulsive gambler in his own right with an expensive lifestyle, to boot – began wagering on ball games, at times against his own team. Measures to ensure that he did not lose such bets included urging Reds teammates, particularly the starting pitcher, not to overexert themselves. Although the extent of Chase game-fixing efforts is modest when compared to the 1,919 major league games that he appeared in, his suspicious performance did not escape the attention of Reds manager Christy Mathewson. By June 1918, rumor was rampant that Chase was dumping games.6 Two months later, Mathewson suspended Chase indefinitely for “indifferent playing.”7

A formal hearing on the Chase suspension was conducted by National League president John Heydler in late January 1919. Fortuitously for the defendant, Mathewson was overseas on military duty and Heydler found the testimony of Jimmy Ring, a young Cincinnati pitcher propositioned by Chase, to be inconsistent and unpersuasive. While declaring that Chase had acted in “a foolish and careless manner both on the field and among players,” Heydler found “no proof that he intentionally violated the rules” or engaged in game fixing. Chase was, therefore, acquitted of the charges, with his playing eligibility immediately reinstated.8

Shortly thereafter, Prince Hal was signed by New York Giants manager John McGraw, a longtime Chase admirer. In Chicago and elsewhere, both players and the baseball press took notice of this turn of events, a widespread conclusion reflected in a newspaper headline that read “Same Old Game; Hal Chase Gets Whitewashed.”9

*****

Late on the afternoon of October 9, 1919, a ground out to second by Chicago White Sox star Shoeless Joe Jackson brought down the curtain on the World Series and made the Cincinnati Reds baseball’s champions. Unbeknownst to fans, that outcome had been prearranged. Indeed, there had been two separate plots to fix the Series — both initiated by Chicago players, not gamblers.10

Hard-nosed White Sox first baseman Chick Gandil was the original fix mastermind. Gandil consulted with Boston bookmaker Joseph “Sport” Sullivan on how the throwing of the 1919 Series might be financed. He also recruited teammates, including staff ace Eddie Cicotte, for the fix; presided over pre-Series fix meetings; and acted as fix paymaster while the Series was in progress.

New York underworld financier Arnold Rothstein, using Sullivan and trusted business associate Nat Evans as a buffer between himself and the corrupted White Sox players, bankrolled the plot, likely to the tune of $80,000.

No evidence connects Hal Chase to the Rothstein-financed fix scheme. Rather, Chase is implicated in a different World Series fix plot that revolved around “Sleepy” Bill Burns, a former major league pitcher who had turned to dabbling in oil leases.

Burns’s true avocation was gambling. In September 1919, Burns was informed by Cicotte that White Sox players were amenable to throwing the upcoming World Series when the two encountered each other at the Ansonia Hotel in New York City. Burns himself, however, did not have the $100,000 price tag that Cicotte placed on the fix proposal, and attempts by Burns sidekick Billy Maharg to raise the necessary cash from gambling interests in Philadelphia proved fruitless.

Thereafter, Burns and Maharg approached Rothstein about underwriting the fix scheme, first at Aqueduct Racetrack and thereafter in the grill room of a Manhattan hotel. But Rothstein brusquely turned them down.

While all this was going on, Hal Chase was sitting on the bench for the New York Giants, a leg injury having confined him to sporadic pinch-hitting duty. During an unplanned late-September encounter with Burns at the Polo Grounds, Chase was informed of the World Series fix proposition and offered his assistance. Shortly after, Chase connected Sleepy Bill to a figure whose reputation was about as unsavory as his own: former featherweight boxing champ Abe Attell, an occasional Rothstein bodyguard and a fulltime hustler constantly on the lookout for a score.

According to Burns, he met Chase, Attell, and a gambler introduced as “Bennett” in the Ansonia Hotel lobby shortly before the World Series began. Attell falsely informed Burns that Rothstein had changed his mind and would now bankroll the fix.11

From that point on, Burns worked in tandem with Attell and “Bennett” (Des Moines gambler David Zelcer). But there is little evidence that Hal Chase did anything after that to advance either Series fix scheme.

For example, Chase was not in attendance when Sullivan and Nat Evans (using the alias “Brown”)12 met with Gandil, Cicotte, Lefty Williams, Buck Weaver, and Happy Felsch at the Warner Hotel in Chicago to solidify the Rothstein fix. Nor was Chase present when the Black Sox (minus Joe Jackson) conferred with Burns and Attell at the Hotel Sinton in Cincinnati on the eve of Game One.

While the World Series was taking place, Chase was far removed from the action, having accompanied New York Giants teammates on a postseason barnstorming tour of upstate New York and New England. Long-distance betting on the Series, however, reputedly put some $40,000 in Chase’s pocket.13

*****

The public exposure of Hal Chase’s game-fixing proclivities had nothing to do with the Black Sox Scandal. Rather, he had Cincinnati Reds teammate Lee Magee to thank for that.

Back in 1918, Magee and Chase had placed substantial bets with Boston bookie James Costello, wagering that the Reds would lose a July 25 game to the Boston Braves. The two had then done their worst to deliver that result. When Boston won anyway, Magee provided Costello with a $500 personal check to cover his bet, but then stopped payment on the check before Costello could collect.14

In time, Costello brought his collection problems to baseball authorities, whose inquiries into the matter led to the uncovering of the fix attempt and the discreet cashiering of Chase and Magee from the game.

The first inkling that something scandalous was afoot emerged when Chase, penciled in as the Giants’ first baseman for the 1920 season, failed to appear at spring training camp. Soon it was revealed that Prince Hal had been quietly dropped from the New York roster.

The Chicago Cubs, Magee’s employer in 1919, unconditionally released him. Accompanied by noise about being unfairly blackballed by baseball, Magee retaliated by filing a hare-brained lawsuit against the Cubs. After testimony from Costello revealed Chase and Magee’s perfidy, a jury required only 44 minutes to no-cause the Magee suit.15

Meanwhile out on the West Coast, Chase was up to his old tricks, including an attempt to rig a Pacific Coast League game. By mid-season, he was persona non grata, unemployable anywhere in professional baseball.16

In September 1920, Chase’s troubles mushroomed when a grand jury in Chicago impaneled to investigate other baseball-related matters shifted its inquiries to the long-rumored corruption of the 1919 World Series.17 Early proceedings, scattershot and largely directionless, segued into alleged game-fixing in the National League.

Considerable attention was devoted to testimony by pitcher Rube Benton, recently a teammate of Chase with the Giants. According to Benton, Chase and Chicago Cubs second baseman Buck Herzog offered Benton a bribe to throw an August 1919 game between the Giants and Cubs,18 an accusation that Herzog adamantly denied in the press.19 For good measure, Herzog alleged that Benton had also won $3,800 betting on the 1919 World Series, his wagering guided by tips from Hal Chase.20

When it came to the World Series fix, the incoherence of early grand jury proceedings led two of the nation’s leading newspapers to identify different villains as the font of the corruption. According to the Chicago Tribune, Hal Chase and Abe Attell were the fix masterminds,21 while the New York Times placed Attell and Chick Gandil, assisted by Bill Burns, in that role.22

Days later, however, clarity and focus were supplied to the proceedings by a Philadelphia newspaper interview of ballplayer-turned-gambler Billy Maharg. According to Maharg, Games One, Two, and Eight of the Series were thrown by eight White Sox players in return for a promised $100,000 payoff from gamblers.23 Eddie Cicotte, Bill Burns, Abe Attell, Arnold Rothstein, and Maharg himself played the principal parts in this telling of the Series fix.

Hal Chase went unmentioned in the Maharg exposé. And the absence of Chase’s name would become a minor but noteworthy feature in the confessions of scandal actors that followed.

One day after Maharg’s interview was published, first Eddie Cicotte and then Joe Jackson were swiftly summoned for interrogation at the law office of Alfred S. Austrian, corporate counsel for the Chicago White Sox. Both men testified before the Cook County grand jury and admitted to accepting a cash payoff in return for agreeing to participate in the World Series fix. This author’s forensic analysis of the Cicotte and Jackson statements/testimony can be found elsewhere.24 For our purposes here, it is significant that no mention of Hal Chase can be found in either Cicotte’s or Jackson’s accounts of the fix.

The interrogation process subsequently repeated itself the next day with Lefty Williams, who also failed to mention Chase’s name in his grand jury testimony. Like Jackson, Williams identified Chick Gandil, Bill Burns, and Abe Attell as the fix promoters in Cincinnati. And earlier at the Warner Hotel in Chicago, Williams said, Sox players had been propositioned by Sullivan and Brown, the gamblers from New York.25 Chase appears in neither scenario.

Later that week, Happy Felsch confessed to his involvement in a newspaper interview. Felsch knew little about the World Series fix financing, but was willing to believe published reports that Abe Attell (whom he did not know) was behind the plot. But like Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams, Happy made no mention of Hal Chase being involved.26

However inexact and tenuous the evidence against him before the grand jury, Chase was among the five gamblers charged with World Series-related conspiracy and fraud in the original Black Sox indictments returned in late October 1920. And he remained among the accused when superseding indictments expanding the roster of gambler defendants were filed in March 1921.

Any inquiry into Chase’s connection to the Series fix that might have been pursued during a trial, however, was stymied by Cook County prosecutors’ inability to procure Chase’s extradition from California. Applications to that end were denied.27 As long as he stayed out of Illinois, Chase was effectively immune from prosecution.

Hal Chase was virtually a cipher during the Black Sox criminal trial proceedings. The only apparent mention of his name came during the testimony of gambler defendant-turned-State’s star witness Bill Burns. Sleepy Bill placed Chase at the hotel meeting where Abe Attell and Bennett/Zelcer represented themselves to Burns and Billy Maharg as the fix agents of Arnold Rothstein.28 Otherwise, nothing.

Notwithstanding presentation of a strong and unrefuted prosecution case against defendants Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, and Lefty Williams, and substantial, if largely circumstantial, proof against Chick Gandil, Swede Risberg, and gambler David Zelcer, the Black Sox jury returned swift not-guilty verdicts on all charges against all the accused on August 2, 1921.29

Days later, Cook County State’s Attorney Robert E. Crowe administratively dismissed the indictments still pending against Hal Chase and the other fugitive defendants. Chase was not among the ballplayers banished from organized baseball by the draconian edict of Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, and he was never formally placed on baseball’s permanently ineligible list either.

Nevertheless, Chase was an untouchable, forced to play out the waning days of his career in forsaken outlaw baseball circuits. He then slipped into near-oblivion. Suffering from the effects of alcoholism and other maladies, Chase died in California in May 1947. He was 64.

*****

Given the passage of time and gaps in the historical record, some aspects of the 1919 World Series fix will forever remain unsettled. This applies to the role of Hal Chase in the Black Sox Scandal. But from the available evidence, it is difficult to assign Chase anything other than a modest supporting role in the corruption.

If viewed in theatrical terms, the leading parts in our drama would belong to Chick Gandil and Arnold Rothstein, the two indispensable actors in the fix. Without Gandil (and perhaps the counsel of Sport Sullivan), there would have been no player conspiracy to lose the 1919 Series. It was also Gandil who recruited his teammates, most importantly staff ace Eddie Cicotte, to join the cabal. Gandil served as payoff paymaster during the Series, and it was Gandil who kept the fix operational, notwithstanding the post-Game Two collapse of the collaboration with the Burns/Attell syndicate.

As for Rothstein, he was likely the only one with the ready-cash bankroll necessary to finance the fix of the World Series on relatively short notice. In short, Rothstein made the Gandil-Sullivan fix proposal a reality, supplying the seed money needed to cement enlistment of the skittish Cicotte before the Series commenced and the post-Game Four cash (probably about $40,000) that kept the fix going when the corrupted Sox may have gotten restless.

Major supporting roles, obviously, must be allotted to Cicotte and Sullivan, and to malleable Lefty Williams, as well. With the 1919 Series elongated to a best five-of-nine match, two White Sox starting pitchers, not just one, were needed if success of the fix plot was to be assured.30 And having Williams join the fix conspiracy achieved that goal, as he and Cicotte managed the five necessary World Series game losses entirely between themselves.

Another significant scandal actor is Bill Burns – not because of his part in the secondary conspiracy to fix the Series result, but his status as star prosecution witness at the Black Sox criminal trial. Without the Burns testimony, even less of the fix dynamics would be known than is the case now.

That said, even if the Burns/Attell conspiracy never gone through, the 1919 World Series would still have been corrupted. Remember, prior to accepting the fix proposition of Bill Burns and Abe Attell, eight Sox players had already joined a conspiracy to throw the Series in return for payoffs offered by agents of Arnold Rothstein. And once those players took Rothstein’s money, the fix could not be undone as AR was not a man lightly to be double-crossed.

This reality reduces Hal Chase to, at most, a subsidiary role in the Black Sox Scandal. Though Chase may have facilitated the short-lived Burns/Attell conspiracy, that plot had relatively little effect. The Rothstein-financed plot was the scandal’s main event. If the players followed through on their agreement with the Rothstein forces, the World Series fix die was cast. The White Sox would lose the Series regardless of any secondary fix agreement mediated or brokered by Chase. Again, in dramatic terms, this reduces Chase’s role to that of a secondary actor in a Series corruption spinoff.

The fact that Chase, like other fix insiders, may have profited handsomely from informed Series wagering does not change this assessment, or elevate him to a position of importance in the hierarchy of Series fix figures. Same for the notion that Chase served as a fix role model and/or that his exoneration by NL President Heydler in February 1919 inspired the ensuing Series fix. That is no more than fanciful speculation, unsupported by any tangible evidence.31

The historical record provides no basis for attributing the corruption of the 1919 World Series to anything other than player/gambler greed and the assumption that corruption of the Series outcome was a low risk/high reward venture. In the final analysis, and however fascinating a character he may have been, Hal Chase played no more than a bit role in the Black Sox Scandal.

Notes

1 Martin Kohout, “Hal Chase,” SABR BioProject, accessed online at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/hal-chase on May 5, 2023. An earlier version of the Chase profile originally appeared in Deadball Stars of the American League, David Jones, ed. (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2004).

2 Babe Ruth, Cy Young, Bill Dinneen, Ed Barrow, and Pants Rowland were among the baseball peers who considered Chase the best fielding first baseman that they had ever seen, per Kohout.

3 Fuller treatment of Chase is provided in Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of the Game (Toronto: Sports Classic Books, 2004), and Martin Donell Kohout, Hal Chase: The Defiant Life and Turbulent Times of Baseball’s Biggest Crook (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2001). Also of interest is Ed Dinger, A Prince at First: The Fictional Autobiography of Baseball’s Hal Chase (McFarland, 2002).

4 Reigning heavyweight champion Jess Willard for example, was absent from the ring after his March 25, 1916 successful title defense against Frank Moran until his third-round knockout by challenger Jack Dempsey on July 4, 1919.

5 The ebb-and-flow of game fixing is best left for another essay. For here, suffice it to say that after the expulsion of four Louisville players for game-fixing during the 1877 National League pennant race, verifiable instances of major league game fixing became few and isolated until 1917.

6 Dewey and Acocella, 263-268.

7 “Matty Suspends Hal Chase for Indifferent Playing,” Chicago Tribune, August 8, 1918: 14; “Hal Chase Suspended by Christy Mathewson,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, August 8, 1918: 10; and elsewhere.

8 “Chase Not Guilty,” Baltimore Sun, February 6, 1919: 9; “Hal Chase Cleared of Gambling Charge,” Chattanooga News, February 6, 1919: 12; and elsewhere.

9 (Lima, Ohio) Times-Democrat, February 6, 1919: 10. A baseball gambling scholar has described the Heydler ruling as “without a doubt the greatest whitewash in the history of baseball.” Daniel E. Ginsburg, The Fix Is In (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1995): 92.

10 This does not include reputed mid-Series efforts to reinvigorate the fix by a coterie of Midwestern gamblers after the White Sox unexpectedly won Game Three.

11 Deposition of Bill Burns for Joe Jackson’s civil breach of contract lawsuit against the White Sox, October 5, 1922.

12 The true identity of “Brown” was long a mystery. Neither the corrupted Sox players nor Chicago prosecutors knew who he was. In October 1920, this shadowy figure was indicted under the name “Rachael Brown,” the pseudonym of Abraham Braunstein, a small-time Manhattan gambler unconnected to the fix. That “Brown” was actually Rothstein lieutenant Nat Evans only came to light decades later. For more, see Bruce Allardice, “Nat Evans: More Than Rothstein’s Associate,” Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter, Vol. 6, No. 1 (June 2014), 14-18; William F. Lamb, “A Black Sox Mystery: The Identity of Defendant Rachael Brown,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Fall 2010), 5-11.

13 According to the grand jury testimony of New York Giants pitcher Rube Benton.

14 More detail on the Magee fiasco is contained in Kohout, Hal Chase, 227-234. See also, Ginsburg, 93-96, and Dewey and Acocella, 263-264.

15 See William F. Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Proceedings (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013), 25-26.

16 See Dewey and Acocella, 314-320; Ginsburg, 264-265.

17 The original subject of grand jury investigation was the report that a meaningless late August 1920 game between the Chicago Cubs and Philadelphia Phillies had been rigged. The panel was also charged with probing Chicago’s lucrative baseball pool selling rackets.

18 The wholesale disregard of the mandate that grand jury proceedings remain confidential allowed publication of Benton’s testimony, as well as newspaper revelation of virtually everything else said behind closed doors.

19 Chicago Daily Journal, September 23, 1920. A story about crookedness in baseball with a Rube Benton byline appeared the same day in the Chicago Evening American.

20 As reported in the Chicago Daily News, Chicago Evening Post, and elsewhere, September 24, 1920.

21 “Inside Story of Plot to Buy World’s Series,” Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1920: 1.

22 “Grand Jury Hears World Series Plot,” New York Times, September 25, 1920: 19.

23 James C. Isaminger, “Gamblers Promised White Sox $100,000 To Lose,” (Philadelphia) North American, September 28, 1920: 1.

24 See William F. Lamb, “Reluctant or Ringleader? Eddie Cicotte’s Role in the Fix,” Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter, Vol. 12, No. 2 (December 2020), 3-9; “An Ever-Changing Story: Exposition and Analysis of Shoeless Joe Jackson’s Public Statements on the Black Sox Scandal,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2019, 37-48.

25 See transcript of Williams grand jury testimony at GJT 26-29 to GJT 27-17; GJT 28-11 to GJT 29-4; and GJT 31-30 to GJT 32-8 in Chicago History Museum, Black Sox Scandal Collection.

26 “‘I Got Mine, $5,000’ – Felsch,” Chicago Evening American, September 29, 1920: 1.

27 The Cook County State’s Attorneys Office forwarded a copy of the indictment rather than the requisite governor’s warrant to authorities in California, and then inexplicably failed to cure this defect in their papers during ensuing courtroom proceedings. The request to extradite Chase to stand trial in Chicago was therefore denied by a California Superior Court sitting in San Jose.

28 Only fragments of the Black Sox criminal trial record have survived, but verbatim accounts of the testimony of prosecution star witness Bill Burns were published in newspapers nationwide. See e.g., “Burns Now Says Sox Formulated Sell-Out Plan,” Albuquerque (New Mexico) Morning Journal, July 2, 1921: 4; “Baseball Players Made Sell-Out Proposition,” Norwich (Connecticut) Bulletin, July 21, 1921: 1.

29 The writer’s view regarding certain of the acquittals is explained in “Jury Nullification and the Not Guilty Verdicts in the Black Sox Case,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2015.

30 The writer is among the Black Sox Scandal researchers who believe that corruption of the 1919 Series would have been difficult, if not impossible, had 1917 World Series standout Red Faber been healthy and able to assume the spot of the White Sox’s number two starter instead of Lefty Williams.

31 A September 28, 1920 affidavit prepared for but never signed by Eddie Cicotte alleged that discussion of the Series fix was prompted by “talk that somebody offered” $10,000 to Chicago Cubs players to throw the 1918 World Series to the Boston Red Sox. Cicotte’s statement in Alfred Austrian’s office and his subsequent grand jury testimony do not make this assertion.