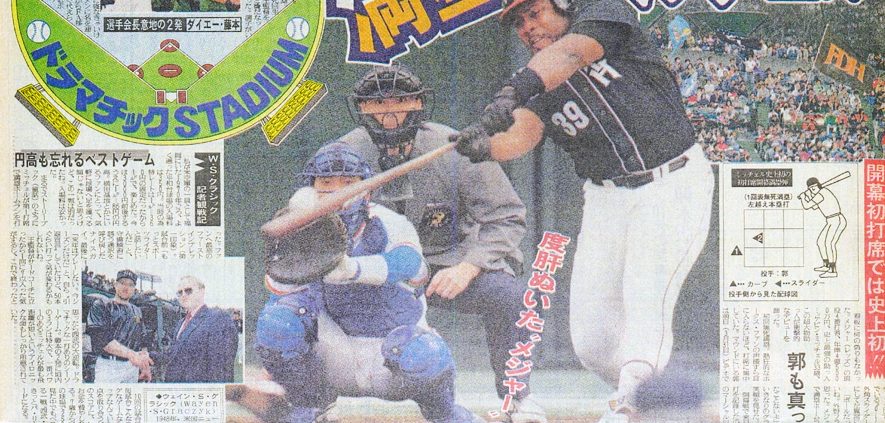

Kevin Mitchell’s Grand Slam Debut in Japan

In an image captured on the front page of the Hochi Shinbun newspaper, Kevin Mitchell hits a grand slam in his Japanese debut on April 1, 1995. (Courtesy of Tomotada Yamamoto)

Baseball was established in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. Some Cubans might say “Batos” is the origin of baseball, but I believe this sport is based on democracy, the soul of the United States of America, so I am sure it was established in the United States. Baseball was imported to Japan in the late nineteenth century, then soon was transformed to “Yakyu” in the early twentieth century.

“Yakyu” has a different foundation from American baseball, because it is based on “Konjyo” — the guts forced to show to obey the orders from the managers or coaches. Yakyu is not based on a democratic philosophy.

Historically, Japanese baseball players, generally the elites from the famous universities – Waseda, Keio, or Meiji – fanatically imported the newest baseball technologies from the United States, to catch up to the strength of American baseball teams.

This continues to the modern day. In 2024 it is still common in Japanese baseball to place a high regard on imports from US baseball — or the Meee-Jyaa-Liigu, as Japanese speakers pronounce “Major League Baseball.”

In 1987, Japanese baseball fans experienced the great “shock” of Bob Horner’s arrival. The former Atlanta Braves star came to Japan “accidentally” — due to illegal collusion by MLB owners during the free agent signing period — and joined the Yakult Swallows. He appeared in only 93 games but hit .327 with 31 home runs and 73 RBIs. This phenomenon was called “Horner Senpu (Storm).”

Horner’s resume was similar to that of Kevin Mitchell, a former National League MVP with the San Francisco Giants. During the 1994 season, shortened by a labor dispute that cancelled the World Series, Mitchell hit .326 with 30 home runs and 77 RBIs in 95 games as the cleanup hitter for the Cincinnati Reds. That offseason, Mitchell decided to come to Japan to play for the Fukuoka Daiei Hawks as the highest-paid player in Japanese professional baseball history at the time, at almost $5 million annually.

Baseball fans in Japan expected him to dominate professional baseball, as Bob Horner did in 1987.

And that day came. On April 1, 1995, Mitchell gave a thrill to Japanese baseball fans in his very first at-bat with the Hawks. In the bottom of the first inning, with the bases loaded and on a 1-and-0 count, Mitchell swung at a slider from Seibu Lions ace pitcher Taigen Kaku. Mitchell drilled a missile into the left-field bleachers. Through 2023, it was the only grand slam in a first at-bat in the first inning in Japanese professional baseball history.

“Japanese baseball is wonderful. I love the fans in Japan,” Mitchell said afterward.

But the acclaimed Japanese baseball magazine Weekly Baseball of Japan had warned about Mitchell’s behavior in a March 20 article:

“He is a real superstar of MLB. But he is not the role model. He is rude to keep in times, and rude to make promises. He was almost accused of domestic violence, and he was raised in the manner of gangsters in San Diego. He dropped out of school, and he is so notorious for rude behavior. He is obviously a talented person, praised by Tony Gwynn, or Matt Williams, and he will dedicatedly play for a manager who understands him, Dusty Baker, but it is not sure that the most famous role model in Japanese professional baseball, Sadaharu Oh, would be loved by him.”

The article accurately predicted Mitchell’s future. He left a Hawks game on April 14 because of a fever, and in his next game, he suddenly felt pain in his right knee while running to catch the ball. He was seen by the team doctor, but when the doctor reported uncertainty about his knee problem, Mitchell decided to go to a doctor he knew in the United States. He suddenly left Japan on May 26, without permission from the Hawks.

Mitchell’s actions provoked anger in Japan. He was criticized by the media and despised by many fans. The Hawks decided to void his contract, but he suddenly came back to Japan on July 21 and the team reinstated him. He recorded 15 hits, including two home runs, and drove in nine runs in 33 plate appearances from July 29 to August 8. Then he injured his right knee again and returned to the United States on August 11 –without the team’s permission again. This time, he didn’t come back.

Almost everybody in Japan was angry at Mitchell, but this reaction may not have been fair. His right-knee problem should have been thoroughly checked by an American doctor, even if the doctors in Japan could not solve the problem. The Hawks should have given him permission to go back to the United States. But in 1995, “Konjyo” was still dominant in Japan, so many thought Mitchell should have stayed and obeyed orders, hiding his pain for the sake of the team.

In all, Mitchell appeared in 37 games for the Fukuoka Daiei Hawks, batting .300 with eight home runs and 28 RBIs. One still ponders, if he had stayed healthy and spent a full season with the team, how many wonders he would have shown in Japan. Mitchell was definitely a dream at that time, but this dream faded away in 1995, while pitcher Hideo Nomo gave wonders to baseball fans in the United States.