Sunday Baseball Comes to Shibe Park — Very Late

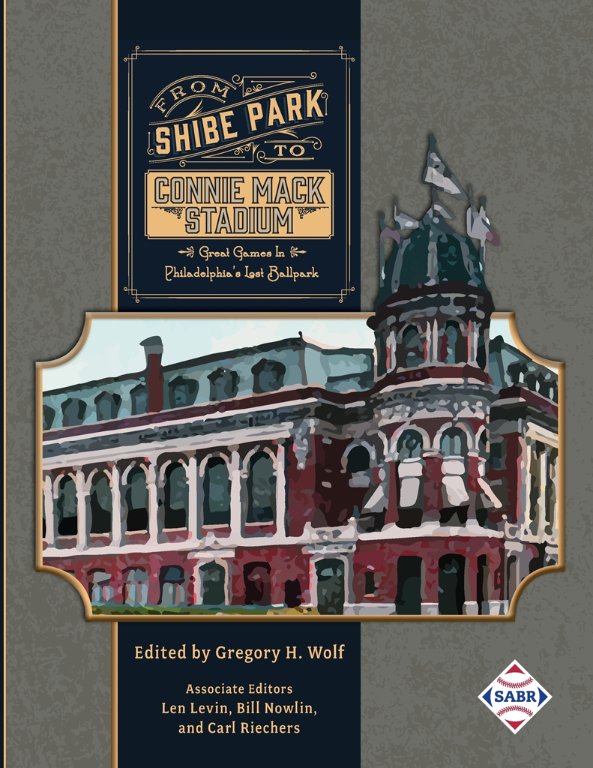

This article was originally published in “From Shibe Park to Connie Mack Stadium: Great Games in Philadelphia’s Lost Ballpark” (SABR, 2022), edited by Gregory H. Wolf.

“You see, Mr. Gaffney, in 1794, when this law was passed, the communities were very small, consisting of little towns and villages where they had cock-fighting, dog-fighting, and other sports and games which no doubt did create a noise which disturbed the entire community. But conditions have changed since that time and I don’t believe they had any baseball games in 1794. You see we must view this subject in a sensible light. – Judge Frank Smith comments to Philadelphia City Solicitor Joseph Gaffney at a hearing in Philadelphia, August 19, 19261

Dating back to the nineteenth century, cities and towns were uncomfortable with baseball being played on what was, and is, to most Americans, the Sabbath, a day for rest and prayer. Laws impacted play in both the major leagues and the minor leagues. Battles over Sunday baseball continued into the twentieth century and many of us can still remember that when we were growing up, there was little if any Sunday night baseball, and that Pennsylvania law dictated that no inning could commence after 7:00 P.M. on Sundays.

Dating back to the nineteenth century, cities and towns were uncomfortable with baseball being played on what was, and is, to most Americans, the Sabbath, a day for rest and prayer. Laws impacted play in both the major leagues and the minor leagues. Battles over Sunday baseball continued into the twentieth century and many of us can still remember that when we were growing up, there was little if any Sunday night baseball, and that Pennsylvania law dictated that no inning could commence after 7:00 P.M. on Sundays.

During the early days of Organized baseball, several major-league teams would venture to remote beach locations for Sunday games. Philadelphia was no exception.

The Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association ventured to Gloucester Point in New Jersey to play on Sundays for three seasons after the Gloucester City Council approved the games on May 19, 1888.2 Of course, this met with some opposition. These words appeared in the Harrisburg Independent on June 27, 1888: “Sunday baseball and Sunday beer go hand in hand, the one being necessary to invigorate the other and both being of the character of a defilement of a day which all laws, divine and human, demand shall be kept holy.”3 By July 1888 there was talk of impeaching the mayor of Gloucester for failing to enforce laws against beer and baseball. Boats would ferry fans to the resort where not only was there a ballgame, but an opportunity to buy beer. As noted in the Philadelphia Inquirer, “Every Sunday evening, the ferry boats landing at Christian and South streets emit hundreds of drunken, quarreling, swearing discordant men and women, who create disturbances and street fights and generally wind up by obtaining a rest in the station house cells.”4 On September 1, 1889, Frank Fennelly, then playing with the Athletics, hit the 32nd of his 34 major-league homers at Gloucester Point.

Sunday-play bans in most major-league cities continued into the twentieth century. Only six of the 16 major-league teams played Sunday home games in 1902. During the first two decades of the twentieth century, one by one, the bans were lifted.

During the First World War, Connie Mack offered a suggestion that Shibe Park be used for Sunday games to benefit the war effort. The idea was to open the ballpark on Sundays for the 20,000 servicemen stationed in Philadelphia and have games between enlisted men and professional teams.5 But the idea met with opposition from the clergy. Reverend James M.S. Isenberg said, “I think it is a poor way to teach our young men to violate the Lord’s day when we believe our cause is right.”6 Nothing came of the effort and Sunday baseball did not come to Philadelphia in 1918.

However, in 1918, Washington hosted Sunday baseball for the first time, and in 1919 the three New York teams followed suit. The last two states holding out against Sunday baseball were those cradles of democracy, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania.

In Philadelphia, the Athletics decided to rail against the state’s Blue Laws, enacted on April 22, 1794, and the first Sunday game was played at Shibe Park on August 22, 1926. Lefty Grove pitched the Athletics to a 3-2 win over the White Sox.

On August 19, the Thursday before the game, the pros and cons of Sunday baseball were argued at a hearing after Connie Mack sought an injunction preventing any interference by the authorities, including Mayor Freeland Kendrick. During the hearing, Charles G. Gartling, the Athletics’ counsel, argued that the police had no right to enter the grounds and break up a game. He maintained that the only recourse of the police would be to arrest the players the next day and fine them $4. A contrary view was expressed by Philadelphia City Solicitor Joseph P. Gaffney. Gaffney maintained that professional baseball games on Sunday constituted a breach of peace, and thus could be stopped by the police.7

Among those who gave testimony was Connie Mack. An impressive figure on the witness stand, he said that at the Sunday games he had witnessed in other cities, fans were better dressed and better behaved than crowds on other days. Hearing that, Gaffney came up with a hypothetical situation. “Suppose in the ninth inning, two men were out, three were on base, the home team two runs behind, and the batter hits a home run. Would the crowd lose his control and respect for Sunday?” Mack responded, “I can see the crowd just rising quietly and leaving.” The courtroom broke into laughter and the judge had to use his gavel.8

The injunction was issued by Judge Frank Smith, who held that “baseball does not tend to immorality or the corruption of youth” and added that baseball took a person “out into the open, who might otherwise spend his time to his own disadvantage.”9 The game was played in somewhat intemperate weather, but Mack was pleased that the fans had the opportunity to witness the event. He said, “The most severe critics and opponents of Sunday baseball, at the game, would, I am sure, be satisfied that the club gave everything it had for the enjoyment of a large number of people and, as a result, their feelings toward Sunday baseball would be changed. I wish all those who oppose Sunday baseball could have been here today. They would see that we are not causing a lessening in Church attendance.”10

As with much of the debate concerning Sunday baseball, there was some levity displayed in the reporting. This notice appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer on August 21, 1926: “(On August 20) Members of the Germantown Boys Club were guests of Cornelius McGillicuddy, that wicked advocate of Sunday baseball. The loud rooting disturbed the peace of an organ grinder with a monkey, who was working the east side of Twentieth Street between Lehigh and Somerset.”11

On Sunday, August 22, more than 12,000 fans braved the elements and saw the Athletics defeat the White Sox, 3-2, in 1 hour and 45 minutes. Rain had intermittently pelted Philadelphia for the week leading up to the game and most observers were surprised that the game was played at all. As noted by James C. Isaminger in the Philadelphia Inquirer, the game “was played under distressing weather conditions and started in an exasperating drizzle that threated at any minute to turn into such a fury of a storm as to quickly chase the players off the field. There was some luck left for the wicked Sunday exploiters of baseball for the ominous downpour never came, and rain stopped entirely by the middle of the game to be renewed later in the form of a scotch mist.”12 (In weather jargon, scotch mist is a light, steady drizzle.)

Injunction or not, the opponents of Sunday baseball in Philadelphia were not about to allow Sunday baseball to continue without a court battle. The game on August 22 was the only Sunday game scheduled and played in Philadelphia that season. Mayor Kendrick and City Solicitor Joseph Gaffney were openly opposed to Sunday baseball and noted that Judge Smith’s ruling came in a preliminary hearing. No arrests were made on Sunday because a Pennsylvania law enacted in 1705 made it illegal to arrest people on Sunday except for felony or breach of peace. The city officials vowed to seek a reversal of Judge Smith’s ruling and the clergy was adamant. Reverend William B. Forney of the Philadelphia Sabbath Association said, “Sunday’s game was the most outrageous thing put on in any civilized community. The crowds yelled and screamed enough to disgust any one. I was ashamed that such an exhibition could be held on the Sabbath.”13

The matter did wind up in the courts. On October 28 the Dauphin County Court ruled that professional Sunday baseball constituted “worldly entertainment” and was therefore illegal. On June 25, 1927, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, in a 5-to-2 decision upheld the ruling that professional baseball is a business and worldly entertainment and, as such, was in violation of the Blue Laws of 1794. Thus, Sunday baseball remained banned in Pennsylvania.14

After a referendum in 1928, the ban in Boston was lifted in 1929, leaving the three Pennsylvania teams as the only teams without Sunday baseball.

But the Blue Laws were not uniformly applied in Pennsylvania. Minor-league baseball was played on Sunday in various locations, but the courts would not allow Sunday baseball at the major-league level. In Philadelphia on Sunday June 14, 1931, the Penn Athletic Club hosted the Englewood (New Jersey) Athletic Club in a game at the Baker Bowl, the Phillies ballpark. It was a poorly played affair with seemingly as many errors as hits as the hosts won 14-12.15

Sunday baseball became an economic necessity, especially for the Athletics. During the court hearing in 1926, the Athletics president, John R. Shibe, had testified that the team could make an additional $20,000 per game on Sundays. Although they had been in the World Series from 1929 through 1931, their attendance slipped as the Depression worsened. It declined from 839,176 in 1929 to 721,636 in 1930 and 627,464 in 1931. In 1933, attendance was down to 297,138.

In 1931 a bill allowing Sunday baseball was introduced in the state legislature by South Philadelphia’s Stephen C. Denning, but the opposition remained strong. Despite the extraordinary measure of bringing one pro-Sunday-ball legislator, who had been ill, to the pivotal vote by ambulance, the measure failed to pass.

Connie Mack maintained that his Athletics, despite winning pennants from 1929 through 1931, were losing potential revenue by the absence of Sunday baseball, necessitating the selling of Al Simmons, Jimmy Dykes, and Mule Haas to the Chicago White Sox for $100,000 after the 1932 season.

But the forces against the 1794 Blue Laws had picked up momentum, and the bills enabling Sunday baseball and other types of recreation moved forward. No fewer than six anti-Blue Laws bills were introduced in the early ’30s. Rallies supporting the measures included a large gathering at the Elks Club, meeting at the behest of the Association for the Encouragement and Regulation of Sunday Sports and featuring Philadelphia Councilman W. W. Roper.

At the rally, James J. Walsh, managing secretary of the Market Street Merchants Association, tried to strike a conciliatory tone. He said, “Our country is getting diminishing returns from its youth, diminishing returns from its home life, diminishing returns from its laws, while restrictive and prohibitive legislation, or the demand for it, is ever mounting. The Blue Laws of Pennsylvania should be revised – and by such a revision we do not by any means intend a ‘wide-open city.’ A good baseball game on Sunday is not a crime; a good musical concert certainly should not be disallowed.”16

A public hearing on a bill sponsored by state Representative Louis Schwartz of Philadelphia was scheduled for January 31. This bill, limited in scope, allowed for the playing of baseball and other outdoor sports (excluding boxing, wrestling, hunting, and fishing) on Sundays between 2:00 P.M. and 6:00 P.M. The bill called for referendums to sanction these activities. Proponents of the legislation (including Roper, Walsh, Adolph Hirschburg of the American Federation of Labor, Edward A. Kelly, and Connie Mack) were heard as were opponents led by Reverend W.D. Forney of the Lords Day Alliance.17 Mack testified that it had been his experience that in seven American League cities, Sunday games were played with no disorder. He said, “If I felt for a moment that Sunday baseball was going to be detrimental to morals of people of Philadelphia, our gates would never open.”18

Councilman W.W. Roper’s testimony was compelling. He said, “The Pennsylvania Blue Laws of 1794 undoubtedly reflected the spirit of those times. Conditions today are totally different from what they were 150 years ago. Regulations designed for the primitive society of the eighteenth century cannot be inflicted upon us in this age without injury to the health and welfare of our people. Respect for law is somewhat like respect for an individual. Neither is given gratuitously – they must both be earned. And respect for law can only be earned through its appeal to the sense of justice. Today, a large majority of the people demand the right to enjoy orderly healthful recreation on their day of rest.”19

Dr. Robert Bagnell of the State Council of Churches countered by saying, “We are opposed to any effort to lessen the sanctity of the day or open it to the inroads of commercialism. Don’t let the camel get his nose under the tent. Once the camel gets inside the tent, Sunday motion pictures will follow.”20

The legislation was passed in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, but was stalled in the Senate. Indeed, the bill was voted down on March 14. But proponents did not give up the fight. The bill was reconsidered in the Senate and amendments were added, the key one being a call for a statewide referendum the following November, killing the idea of Sunday baseball for 1933. On April 11, 1933, the amended bill was passed. After much deliberation, and at the urging of Connie Mack, Governor Gifford Pinchot signed the bill into law on April 25.21

“While the spectators uncorked some healthy American rooting, it was an orderly crowd, and not one untoward event marked the first game under the law sponsored by Representative Louis Schwartz, who watched the game from a box.” – Philadelphia Inquirer, April 8, 193422

In November of 1933, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh said “yes” to allowing Sunday baseball. The first legal Sunday baseball game in Philadelphia was played on April 8, 1934, as the Phillies took on the Athletics in an exhibition game at Shibe Park. A week later the teams opposed each other at the Baker Bowl. The Athletics hosted Washington in the first legal regular-season Sunday game on April 22. Before the game, as 20,306 spectators looked on, Connie Mack gave a silver loving cup to Representative Schwartz for his role in passing the enabling legislation.23 One week later, the Pittsburgh Pirates hosted Cincinnati and the Philadelphia Phillies hosted the Dodgers in the first National League Sunday games in those cities.

SOURCES

For further reading on the subject of Sunday baseball, the author recommends:

Bevis, Charlie. Sunday Baseball: The Major Leagues’ Struggle to Play Baseball on the Lord’s Day, 1876-1934 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2003).

DeMotte, Charles. Bat, Ball, and Bible: Baseball and Sunday Observance in New York (Washington: Potomac Books, 2013).

1 “Court Will Decide if Sunday Baseball Is Breach of Peace,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 20, 1926: 7.

2 “Sunday Baseball Games at Gloucester,” New York Tribune, May 20, 1888: 2.

3 Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Independent, June 27, 1888: 1.

4 “Still Defying the Law,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 2, 1888: 5.

5 “Sunday Baseball in Quaker City?” Reading Times, May 1, 1918: 11.

6 “Church Opposes Sunday Games,” Harrisburg Telegraph, May 3, 1918: 18.

7 “Court Will Decide if Sunday Baseball Is Breach of Peace,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 20, 1926: 1.

8 “Court Will Decide if Sunday Baseball Is Breach of Peace,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 20, 1926: 7.

9 “Court Restrains Police from Stopping Sunday Ball Game,” Sunday News (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), August 22, 1926: 2.

10 “First Sunday Major league Ball Game in Phila. Goes Over with a Bang,” Boston Herald, August 23, 1926: 6.

11 “Macaroons,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 21, 1926: 10.

12 James C. Isaminger, “Grove Hurls Mackmen to Victory in First Sunday Major Game Played Here,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 23, 1926: 16.

13 “Mayor to Continue Sunday Ball Fight,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 24, 1926: 2.

14 “Shibe Inspects Jersey Site for Sunday Games,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 29, 1931: 6.

15 “Pennacs Biff Out Win Over Englewood Rival in Phillies’ Park Fuss,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 15, 1931: 13.

16 “Blue Law Foes Mass to Voice Protest,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 31, 1933: 12.

17 John M. Cummings, “Early Report Scheduled on Sunday Sport,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 31, 1933: 1.

18 Cummings, “Committee Votes for Legalization of Sunday Sport,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 1, 1933: 1, 6, 7.

19 “Committee Votes for Legalization of Sunday Sport.”

20 “Committee Votes for Legalization of Sunday Sport.”

21 “Pinchot Approves Sunday Baseball Ballot by People,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Record, April 26, 1933: 1.

22 Isaminger, “Haslin and Allen Lead Phil Parade in Series Starter,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 9, 1934: 13.

23 Isaminger, “Infield Miscue, Schulte Clout, Send Down A’s,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 23, 1934: 15.