The Chicago American Giants: A History

This article was originally published in “The First Negro League Champion: The 1920 Chicago American Giants” (SABR, 2022).

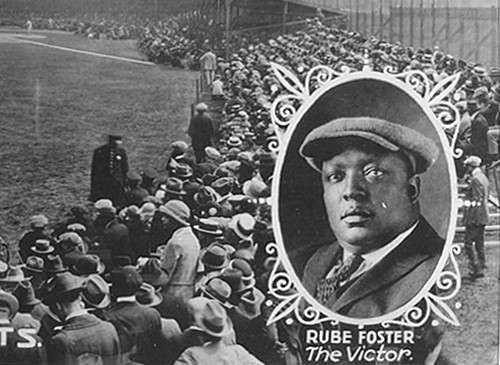

Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants played home games at Schorling Park in Chicago (NoirTech Research, Inc.)

The arc of the history of the Chicago American Giants follows closely with the arc of Black and Negro League baseball in the United States. The story of one cannot be told without the other. The American Giants were born from the baseball genius and business acumen of Rube Foster, a titanic figure without whom any history of the Negro Leagues would also be incomplete. While the name “Chicago American Giants” might be time-stamped with 1911, their history effectively stretches backward an approximate quarter-century to the Chicago Unions from the early years of Black baseball in the Windy City.

The Unions emerged as the city’s top Black team around 1886, and the club soon came under the sponsorship of Frank Leland and other Black businessmen, including W.S. Peters.1 Leland became an influential figure in the establishment of baseball as an institution in Chicago’s Black community. By 1896, the Unions had become a professional club, and Leland’s connections helped to secure playing fields in Chicago at a time when grounds could not be taken for granted. The Unions soon had company when the Page Fence Giants, one of the early powers of Black baseball, moved from Michigan to Chicago in 1899 and adopted the name Columbia Giants.

The Unions and Columbia Giants both enjoyed success and competed in championship series with top Black clubs from New York. By 1901, the Union club split apart with Frank Leland consolidating his faction with the financially tottering Columbia Giants to form the Chicago Union Giants. The following year, a young Texas pitcher already in possession of an outsized reputation joined the Union Giants: Rube Foster. Though Foster joined the Philadelphia Giants in 1904, he returned within a few seasons. Meanwhile, Leland’s team adopted the name Leland Giants in 1905 and, through formation of the Leland Giants Baseball and Amusement Company, secured the financial backing that stabilized the ballclub and positioned Leland as the top Black baseball owner in the Midwest.2

Leland recruited Foster back to Chicago in 1907, and Foster brought several Philadelphia Stars teammates with him, including outfielder Pete Hill and catcher Pete Booker. The American Giants began playing games at South Side Park, attracting good crowds at the home of Charles Comiskey’s White Sox. As Leland became more active in Chicago politics and dealt with health issues, Foster consolidated his position over on-field and off-field affairs. As manager, Foster swapped out players originally brought in by Leland with his own men, an effort that resulted in the 1909 Chicago City League championship.

While learning the business and collecting fees as a booking agent, Foster also aligned himself with Beauregard Mosely, the lead lawyer for the Leland Giants Baseball and Amusement Company, and Major R.R. Jackson, a previous financial backer of Leland. Tensions between Leland and Foster festered and by 1910 the Foster-Mosely-Jackson combination forced Leland out of his own company. Leland announced his plans to form a new baseball club but shockingly lost a lawsuit over the use of the Leland Giants name. Foster and Mosely maintained control over the Leland Giants while Leland formed the Chicago Giants.

The 1910 Leland Giants may have been the finest team Foster assembled for a baseball season, with second baseman Grant Johnson, shortstop John Henry Lloyd, pitcher Frank Wickware, and catcher Bruce Petway supplementing an already strong team. Foster claimed the Black world championship for the Leland Giants with 123 wins against a mere six losses.3

By the following season, 1911, Foster had left the Leland Giants and launched the Chicago American Giants. After barnstorming in the spring, the American Giants played their home opener on May 13 at South Side Park, by now the former home of the White Sox. Foster secured the grounds through a partnership with John Schorling, who had control of the site through his connections to Comiskey.

He renamed the field Schorling Park, which was appropriate considering his layout of $10,000 on renovations4 that included a new 9,000-seat grandstand. Mosely and the Leland Giants gradually withdrew into local baseball, and Leland himself took more interest in politics before his death in 1914. The field was effectively cleared in Chicago for Foster and the American Giants, and Schorling Park became the stage for their ambitions.

Foster signed pitcher Bill Gatewood and third baseman Candy Jim Taylor for the 1912 season, one in which Foster claimed 112 wins from 132 games as well as the “colored” championship. Foster took the American Giants to the West Coast for the 1912-13 winter season, and the team won the California Winter League championship. That became the pattern for much of the decade: The American Giants combined winter barnstorming through the West and South with summer series against the leading clubs of the East and Midwest for unofficial championships of Black baseball.

For the 1913 season, the American Giants returned an almost intact roster except for Wickware. Foster agreed to a championship series with the Lincoln Giants of New York. The teams battled in a tightly contested series in Chicago over a three-week period with outfielder-pitcher Judy Gans outdueling Gatewood in the deciding match to secure a 4-1 victory and the “World’s Colored Championship” for the Lincoln Giants.

Foster soon had competition in his Midwestern backyard as the Indianapolis ABCs emerged as a credible rival. Managed by C.I. Taylor, the club aggressively recruited talent in the face of local competition from the Federal League’s Indianapolis Hoosiers. With a lineup that included C.I.’s brothers Candy Jim, Steel Arm, and Ben, as well as George Shively, the ABCs challenged the American Giants to a championship series. Chicago won seven of 11 games against Indianapolis in 1914 and then claimed another “Colored Championship” after sweeping four games from the Brooklyn Royal Giants. In response, Taylor added Oscar Charleston, Bingo DeMoss, and Dizzy Dismukes in preparation for a 1915 rematch.

After the American Giants won three of five games at Schorling Park in June, the series shifted to Indianapolis in July. The Indianapolis leg was characterized by chippy play on the field and heated rhetoric between Foster and Taylor. The first game was forfeited to the ABCs by the umpires due to alleged stalling by Foster, the specific events of which were hotly disputed. The next day, police intervened twice in an ABCs victory. After Chicago dropped two more games and thus the series, a war of words in the Black press erupted between Foster and Taylor. Despite the results, Foster tried to claim the championship of Black baseball.

Foster set about improving the American Giants ahead of a 1915-16 winter barnstorming tour, adding first baseman (and ex-American Giant) Leroy Grant. The ABCs remained the primary thorn in Foster’s side in 1916, and a series of games in Indianapolis in October and November ended again in controversy. Foster removed his team from the field in one game after an argument with an umpire about whether he could wear a glove in the coaching box. The question of the championship remained the subject of recriminations between the two managers, with the budding rivalry providing mixed publicity for Black baseball.

Before the 1917 season, Foster signed second baseman Bingo DeMoss and pitcher Cannonball Dick Redding. The American Giants seemed poised for success, but World War I affected baseball as players were drafted into the armed forces and reductions in playing schedules were necessitated. Nonetheless, between the American Giants and his fledgling booking agency, Foster squeezed in enough baseball to keep the turnstiles moving at Schorling Park. To assist with the war effort, the American Giants and ABCs barnstormed through major-league ballparks, with Chicago taking 15 of 19 games.5

Lloyd and Wickware moved east with the Brooklyn Royal Giants, furthering weakening the team, although former foe Judy Gans was now in the fold. Chicago scheduled games in the East to take on emerging powers in Hilldale and the Bacharach Giants, but the depleted American Giants were swept for their troubles. Foster added outfielders Oscar Charleston and Cristobal Torriente for the 1919 season, but by this time, a new Midwestern rival was emerging. With several former American Giants in the fold, including player-manager Pete Hill, the Detroit Stars became the next contender for the throne. In a series between the clubs, the American Giants claimed five wins in the first six games before the Stars stormed back with five straight wins. After a delay of a few weeks because of race riots in Chicago, the American Giants won the final two games, 2-1 and 5-3, to take the series in Detroit. The American Giants headed farther east, swinging through New York and Pennsylvania for games against leading Eastern clubs. The successful tours generated a profit of $15,000 for the 1919 season,6 putting the American Giants on solid financial footing.

In the offseason, Foster penned a series of articles in the Chicago Defender on the state of Black baseball. The “Pitfalls of Baseball” became a launching point for another attempt at forming a Black baseball league. This time the efforts proved successful.

After a series of meetings in Kansas City in February 1920 for a league to start play in 1921, the Negro National League brought forward its plans by a year and started play in May 1920. As part of the effort to achieve competitive balance, players were moved across teams. That effort required Chicago to sacrifice Charleston, who returned to Indianapolis.

The American Giants assembled a formidable squad. Dave Malarcher emerged as the regular third baseman, Torriente returned to play center field, and Tom Williams, Dave Brown, and Tom Johnson anchored a solid pitching staff. Chicago won the inaugural NNL pennant with a .717 winning percentage (43-17-2), besting nearest challenger, Kansas City (44-33-2, .571, 7½ games behind) and Detroit (37-27, .578, 8 games behind) by a comfortable margin. After the season, Chicago traveled east to play the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants in a precursor to a Black World Series that matched the top teams from the East and West, with the two clubs staging a series of games at Ebbets Field and Shibe Park.

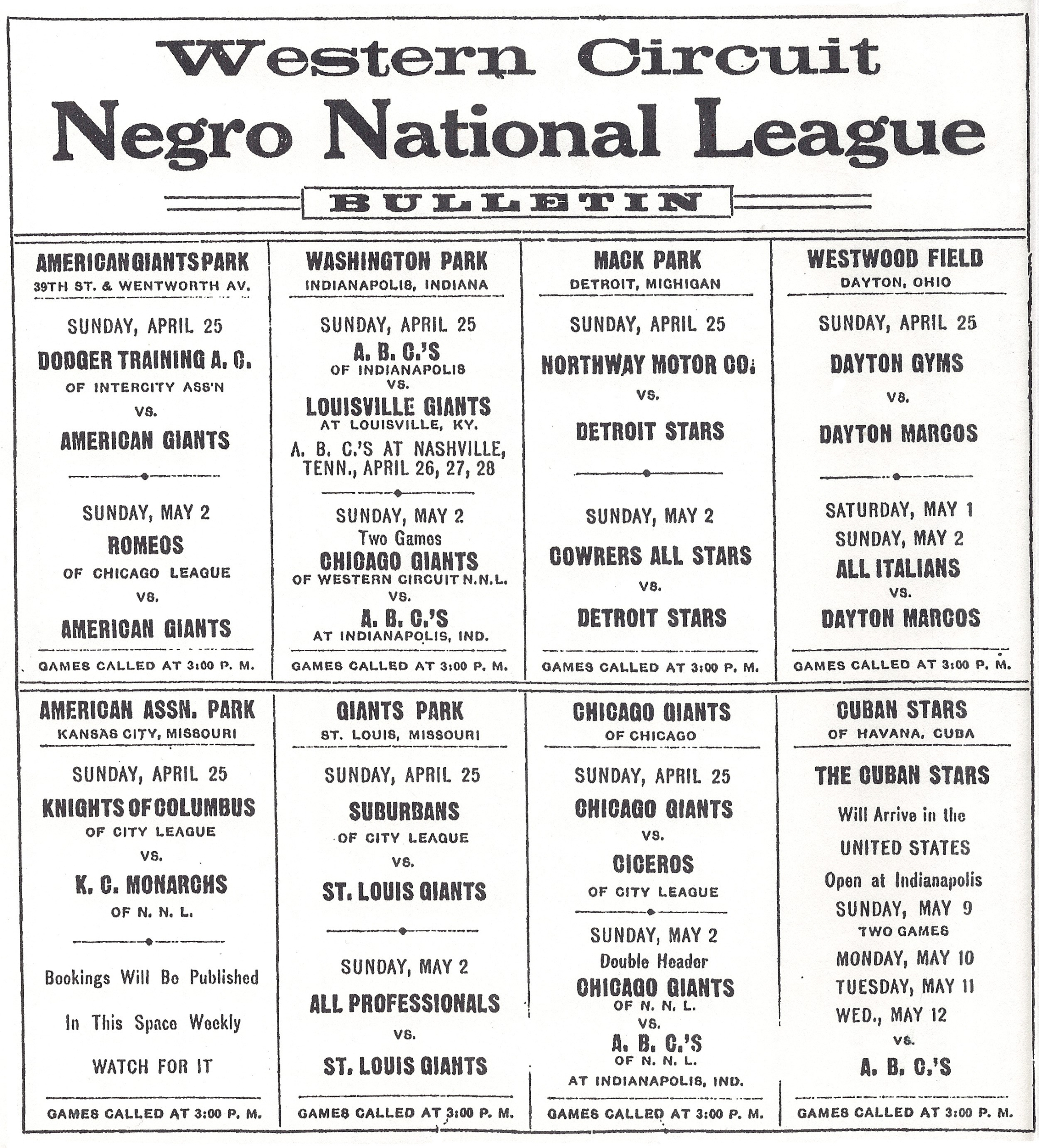

Published on the eve of Opening Day of the Negro National League’s first season in 1920, the Chicago Defender ran a schedule showing the array of games planned for the day. (Chicago Defender, April 24, 1920).

Heading into 1921, Gans left Chicago to become manager of the Lincoln Giants and was replaced in the outfield by Jimmie Lyons from Detroit. Chicago claimed another NNL pennant but this time with a smaller margin over the St. Louis Stars. For 1922, Foster revamped his pitching staff with Ed “Huck” Rile signing from Columbus, former American Giant Dick Whitworth rejoining from Hilldale, and Cuban pitcher Juan Luis Padron landing in Chicago. The purchase of infielder John Beckwith from the Chicago Giants bolstered the lineup for a competitive pennant race. The American Giants narrowly won their third straight pennant on a percentage points basis ahead of Indianapolis, Kansas City, and Detroit.

With the founding of the Eastern Colored League for the 1923 season, the NNL had competition for players, and the American Giants were no exception. Rile and Brown defected to ECL clubs, leaving Chicago without a pitching ace. Rile returned in response to Foster’s edict banning ECL defectors who did not return to their NNL clubs, and led the club with 15 wins. The NNL remained generally stable in the face of ECL competition, with Chicago, Detroit, Indianapolis, Kansas City, and St. Louis on decent footing. To shore up the circuit, Foster recruited the Memphis Red Sox and Birmingham Black Barons as associate members, and he acquired his half-brother, pitcher Willie Foster, from Memphis in the process. In the end, the Monarchs claimed their first pennant, just ahead of the second-place American Giants. An anonymous letter was published in Black newspapers purportedly written by American Giants players, stating that they did not play hard because Foster did not pay well; Foster disputed the letter’s contents.7

The NNL and the American Giants continued to suffer ECL defections before the 1924 season. Oscar Charleston left Indianapolis for Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and the ABCs folded in midseason. To prevent similar actions, Foster used the relative financial largess of the American Giants to keep other clubs afloat.8 The American Giants were not immune to losses to ECL clubs, as Beckwith and Lyons joined the Baltimore Black Sox and Washington Potomacs, respectively, and Chicago again finished runner-up to the pennant-winning Monarchs. It was unclear how long the NNL-ECL war could continue, and a compromise seemed necessary. Indeed, the two leagues agreed to cease player raiding and to compensate for past contract-jumping, accommodations that made possible a Colored World Series between the two league champions. Kansas City defeated Hilldale in a 10-game Series that was staged in multiple cities before disappointing crowds.

The NNL adopted a split-season format for 1925, in which the winners of each 50-game half were to meet in a championship series. Huck Rile was shipped to the revived Indianapolis ABCs to assist with roster balance, but Padron led the staff and even won the Schorling Park home opener with a shutout against Kansas City. The American Giants took three of five against the defending NNL champs, but the auspicious start did not last. During a road trip to Indianapolis in May, Foster was found on the floor of a boarding house bathroom after he had apparently been overcome by natural gas. Neither Foster nor the American Giants seemed to recover as Chicago finished both halves of the NNL season in third place. Kansas City defeated St. Louis for the NNL title, but Hilldale avenged the prior season’s loss in the World Series.

After the season, Foster conducted a makeover of the American Giants. Torriente, DeMoss, and Williams, who had been lineup fixtures since the pre-NNL days, were traded. The Torriente trade yielded George Sweatt from Kansas City; DeMoss and Williams were traded to the ABCs, where the latter was to become player-manager but kept heading east to join Homestead. Padron also departed for Indianapolis, clearing the way for Willie Foster to assume the role of staff ace. When Memphis and Birmingham left the NNL for the Negro Southern League – a circuit not included in the NNL-ECL detente – Foster poached second baseman Charley Williams and third baseman Sanford Jackson from the Memphis Red Sox and outfielder Sandy Thompson from the Birmingham Black Barons, moves that contributed directly to another championship in 1926.

The American Giants had a promising start, but the Monarchs dominated in head-to-head games, leading to a fourth-place finish in the first half of Chicago’s 1926 season. More disconcerting, Foster’s increasingly erratic behavior necessitated his taking a sabbatical to start the second half. Malarcher assumed the managerial duties, the first American Giants skipper other than Foster, and led Chicago to a second-half championship and a date against Kansas City for the NNL title. After falling behind four games to one, the American Giants won the next two to set up a decisive doubleheader on September 29. Willie Foster and Bullet Rogan threw shutout baseball through eight innings before Jackson’s winning run in the ninth leveled the series for Chicago. With darkness approaching, the teams agreed to play five innings to decide the NNL title. Foster and Rogan again took to the mound, with Foster tossing zeros in a championship-clinching 5-0 win. The American Giants next faced the ECL champion Bacharach Giants in an 11-game Colored World Series. The first six games were played in Atlantic City, Baltimore, and Philadelphia, with the Bacharach Giants achieving a 3-1 advantage (with two tied) before the series moved to Chicago. The American Giants won three of the next four to set up a decisive Game Eleven. With Willie Foster on the mound, the game was decided in the ninth inning when Thompson’s liner scored Jelly Gardner for the series-winning run. It is not clear to what extent Rube Foster enjoyed the American Giants’ World Series triumph; he had been committed to an institution and spent his remaining years in care until his death in 1930. Without Foster’s leadership, Black baseball lost an anchor in the face of coming challenges that led to the collapse of both leagues.

Schorling and Foster’s wife, Sarah, jointly represented the American Giants at the combined NNL-ECL winter meetings in advance of the 1927 season, but Schorling began to assert the dominant hand over club matters. Although Thompson and Gardner departed (they returned the following season), Malarcher guided the American Giants to a first-half victory and then an NNL series win over second-half victor Birmingham. The Bacharach Giants again provided the opposition in the 1927 World Series. The best-of-nine series opened in Chicago, and the American Giants swept the first four games before the series headed east. The Bacharach Giants won three of the next four, with the other game ending in a tie. Chicago claimed the ninth and final game to secure another Black baseball championship, but this series was to be the last of its kind. The ECL was on the brink of collapse as economic conditions were declining, a circumstance that had particularly adverse effects for African Americans. With fewer patrons buying tickets, the ECL’s finances suffered, and the league folded in the middle of the 1928 season.

Concerned about making ends meet and fearing that other owners were trying to freeze out his ballpark from staging games,9 Schorling sold out to William Trimble, a White racetrack owner and florist. As Black baseball’s belts tightened in response to challenging economic conditions, the NNL followed suit. Rosters were reduced to 14 players across the league and Trimble closely watched expenses. The club lost Gardner to the Homestead Grays and Sweatt to the US Postal Service; the latter chose steady civil-service work over the low wages offered by Trimble.10 Malarcher departed in midseason because of his own salary dispute. Under outfielder-manager George Harney, Chicago secured the second-half title to force a championship playoff with St. Louis. The Stars edged the American Giants five games to four for the NNL pennant.

Trimble exhibited an increasingly distant style of ownership,11 a notable change from the hands-on approach of Rube Foster. Additional players left for better-paying Postal Service jobs, playing only on weekends, if at all.12 Harney was among the postal workers moonlighting on ball fields, and catcher-first baseman Jim Brown took over in the dugout. Brown could not steer the American Giants back to the postseason as the Monarchs claimed both halves of the 1929 NNL season to obviate the need for a championship playoff. Amid declining attendance, the American Giants scheduled postseason series to make up the shortfall. Strengthened by players from other NNL clubs, the American Giants swept the Homestead Grays in a six-game series at Schorling Park in October and then took four of six against an aggregation of White major-league players.

As the Depression gripped the country, baseball everywhere experimented with lighting systems to stimulate night-game attendance. After the Monarchs brought their portable lighting system to Schorling Park to favorable reviews, Trimble installed his own system.13 The American Giants finished fourth overall in 1930, just above .500 in NNL play. The mediocrity was not inspiring admissions at Schorling Park, and the club again turned to barnstorming as night baseball proved underwhelming. With new owner Charles Bidwill signing the checks, a veritable all-star team in American Giants flannels won three of four games against White major leaguers.

The American Giants were in a state of chaos ahead of the 1931 season. Bidwill seemed unsure what to do with his new asset, and several players, including Willie Foster, left the club. A group of former American Giants emerged under Malarcher’s leadership as the Columbia American Giants, but this club dropped out of the NNL for independent status midway through the season. In fact, there appears to have been little roster consistency across the two seasons, and there are only 24 recorded NNL games for 1931 against 102 league games for 1930.

After the completion of the 1931 season, the NNL collapsed. The Malarcher-led team wound up in the Negro Southern League for the 1932 season, eschewing the East-West League organized by Homestead Grays owner Cum Posey. Robert Cole, a Black businessman who made his money in funeral burial insurance, acquired the lease on Schorling Park. Cole provided a home for the Malarcher club, which was identified as Cole’s American Giants and then as the Chicago American Giants. Willie Foster rejoined the team and Turkey Stearnes was signed to play center field. By whatever prefix, the American Giants rode a first-half championship into a playoff against the Nashville Elite Giants. With a 4-3 series win, the American Giants claimed what was to be their final league championship.

The remaining two decades of American Giants did not come close to replicating the success of the 1910s and 1920s. Schorling Park had provided the American Giants with a benefit enjoyed by few Black ballclubs: an established and permanent home in proximity to where many Black patrons resided. That changed when Cole gave up the lease, which was assumed by White promoters who converted the venue into a dog track. Cole moved the Chicago American Giants to Indianapolis for the 1933 season (and the ABCs were shipped to Detroit). The club joined the revived Negro National League, which included many teams from the short-lived East-West League. Cole signed catcher Larry Brown, first baseman Mule Suttles, shortstop Willie Wells, and pitcher Willie “Sug” Cornelius, and kept the American Giants among the contenders for a while longer. The American Giants and Pittsburgh Crawfords battled each other for the pennant, easily outclassing the rest of the league. In a show of their hegemony for the 1933 season, the teams also dominated the West and East rosters for the inaugural All-Star Game at Comiskey Park on September 10; Willie Foster pitched a complete game in the West’s 11-7 win. The pennant, however, went east as the Crawfords topped the American Giants.

The American Giants returned to Schorling Park in 1934. The dog-track venture had failed when the Illinois legislature had refused to legalize such racing,14 and the ground had been reconverted for baseball. After two seasons with the Chicago Cardinals, Joe Lillard played a more prominent role with the American Giants as the NFL’s own color barrier took hold. Lillard became the regular left fielder and Ted Trent led the pitching staff. The NNL opted for a split season and a season-ending championship series. The American Giants won the first-half title, and again supplied most of the players for the West’s All-Star Game roster; Foster lost this time, dropping a 1-0 decision to the East’s Satchel Paige. The NNL championship series with the Philadelphia Stars was not without problems, however. There was a lengthy delay between the fourth and fifth games and the sixth was marred by a controversy because Stars slugger Jud Wilson was allowed to remain in the game after hitting umpire Bert Gholston. Although Gholston argued initially that he did not see who struck him, Malarcher protested the decision; however, the league caved in even after the assault was verified and Wilson kept playing. After splitting the first six games, Game Seven ended with a 4-4 score because of a local curfew. One more game was played to decide the championship, and Stars ace Slim Jones capped his stellar season by outdueling Sug Cornelius, 2-0.

Malarcher left the manager’s spot after four seasons in his second stint, and catcher Larry Brown took over as player-manager in 1935. The American Giants once again returned a settled core, although Lillard departed the club. Suttles may have provided the season’s highlight with his walk-off home run that decided the All-Star Game. Otherwise, Chicago sank to sixth place in league play. Cole had been losing interest in the American Giants in deference to other business interests, which became an issue with other owners such as Greenlee.15 The American Giants had been losing fans, which made road treks by Eastern clubs much less lucrative than they had been in the Rube Foster days. Cole stepped away from team affairs, and his associate, Horace Hull, assumed control. Citing travel costs, Hull withdrew the American Giants from the NNL before the 1936 season in hopes of anchoring a new alliance of Midwestern clubs.16 That effort failed to materialize, and a mere 18 games are formally recorded for that year as an independent club. Moreover, without league protection, Chicago was raided by NNL teams, with Suttles, Stearnes, Foster, and Alex Radcliffe among those American Giants who found new homes in the East.

Something closer to the normality of a league reason returned with the formation of the Negro American League in 1937. Hull served as chair of the NAL, which occupied a similar footprint as the original NNL. Hull hired Candy Jim Taylor to manage the American Giants, but the Negro Leagues now faced competition from the Dominican Republic in recruiting players. Herman Dunlap and newly returned Alex Radcliffe provided what passed for offense on this weak-hitting team while Cornelius, Trent, and Foster provided consistent pitching. It was enough for the American Giants to qualify for a championship playoff in the NAL’s split-season format, but the Kansas City Monarchs took five out of seven games from Chicago to earn their first of many NAL crowns.

Taylor managed the keep the American Giants competitive over the next two seasons, with first-division finishes among a revolving door of teams in the NAL. Kansas City’s supremacy remained a constant, however. Cornelius and Trent continued to supply innings and Dunlap, Radcliffe, and Wilson Redus led the offense. Pepper Basset joined the American Giants for 1939 after the Crawfords folded in Pittsburgh. Basset, Cornelius, and Radcliffe left after the season, as did Taylor. Redus then replaced Taylor as manager for the 1940 season, but he lasted only one season. The emergence of Donald Reeves as a power-hitting right fielder and Lefty Bowe as a potential ace could not stop the American Giants from settling into mediocrity. In fact, Bowe left during the season to join the traveling Ethiopian Clowns exhibition club. New competition from the Mexican League placed greater pressure on Negro League owners to maintain talent at reasonable wages. The year ended with a Christmas Eve arson that destroyed Schorling Park. The ballpark had been deteriorating for years, emblematic of the debt and decline that had overtaken the once great club.

Memphis native J.B. Martin, who had been active with his hometown Red Sox and eventually assumed the NAL presidency, joined a consortium that invested in the American Giants as a prelude to an eventual takeover. Martin rented Comiskey Park as a replacement for Schorling Park; however, rental costs limited the American Giants to a mere four home games in 1941.17 Martin rejected offers from businessmen to build a new ballpark in Chicago, and the club continued to founder as Martin evinced a greater interest in Chicago politics than in the American Giants. Taylor returned as manager, and he was joined by other recent players such as Basset, Cornelius, and Radcliffe in a partial reunion of the 1939 team. Right fielder and former Crawford Jimmie Crutchfield also was added to the fold. Despite an otherwise creditable roster, the American Giants managed only a fifth-place finish in a six-team league. Taylor recruited Cool Papa Bell, returning from a stint in the Mexican League, for the 1942 season, but the team sank further as a 7-29 record marked the first time the team had finished in last place in the league era of Black baseball.

Taylor left Chicago again to become manager of the Homestead Grays, where he was joined by Bell. Center fielder Lloyd Davenport came west in the Bell trade, and 41-year-old Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Alex’s brother, signed from Memphis as catcher-manager. Double Duty stabilized the team in 1943 and even claimed a first-half championship. Davenport emerged as a top offensive contributor along with Alex Radcliffe (still going at 37) and left fielder John Bissant. Twenty-year-old Art Pennington started to emerge as a key player, and Gentry Jessup assumed the role of ace that he occupied for several seasons. With Birmingham claiming the second-half title, Kansas City’s four-season reign atop the NAL ended; however, the NAL crown was claimed by the Birmingham Black Barons in a five-game series win over Chicago.

Martin’s takeover was complete by the 1944 season, but the club could not build on the success of the prior season. Double Duty departed for Birmingham, with DeMoss returning as manager in his stead. The American Giants slumped in a season of managerial merry-go-round as DeMoss was fired in June and replaced by Davenport. Davenport attempted to join the new iteration of the Pittsburgh Crawfords but ended up being traded to Cleveland as Bissant guided the club through the remainder of a sixth-place season. Martin lured Taylor back as skipper for 1945. With Gentry Jessup, Walter McCoy, and Gready McKinnis leading the staff, and Pennington leading the offense, Chicago improved to fourth place.

The Negro Leagues were turned upside down when the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson before the 1946 season. As is well known, Robinson spent the year in Montreal and made his major-league debut in 1947. As was the case with other Negro League owners, Martin became focused on protecting the Negro Leagues from encroachments by White major-league clubs.18 Foreign leagues also remained a threat, as was evidenced by the American Giants losing second baseman Jesse Douglass, McKinnis, and Pennington to Mexico. Jessup and third baseman Clyde Nelson represented Chicago in the All-Star Game, providing the “highlight” to a last-place finish. After another last-place finish in 1947, Taylor was released from managerial duties. John Ritchey won the NAL batting crown but was poached by the Pacific Coast League’s San Diego Padres without compensation after Martin forgot to offer the young backstop a contract. Though Ritchey never made it to the major leagues, he broke the PCL’s color barrier in 1948. Former American Giant and catcher Quincey Trouppe was acquired from the Cleveland Buckeyes to serve as player-manager for the 1948 campaign. Chicago signed four players from Puerto Rico, including pitcher Roberto Vargas and right fielder Bienvenido Rodriguez. Another newcomer, shortstop Jim Pendleton, provided some offensive spark for the offense, but the American Giants once again finished last.

After Pendleton (to the Dodgers organization) and Pennington (to PCL Portland) departed for potential major-league opportunities, Trouppe and Vargas left due to pay disputes with Martin. Trouppe tired of Martin’s parsimony, especially when the manager’s plan to acquire a young Willie Mays was scrapped by Martin’s refusal to pay $300 in advance money. Trouppe was replaced by Winfield Welch, who had guided Birmingham to NAL pennants in 1944 and 1945. Alvin Gipson emerged to complement Jessup’s pitching as the American Giants contended in the revamped 1949 NAL. Several NNL clubs had joined the NAL after the former circuit’s collapse. One of those clubs, the Baltimore Elite Giants, bested Chicago for the league championship, for which the American Giants had qualified after the Monarchs ceded the spot rather than pay the rent for the ballpark.

Double Duty Radcliffe succeeded Welch for the 1950 season, one in which the American Giants integrated. Chicago signed four White players, including two from the Chicago Industrial League, but none of them saw significant action. The anticipated attendance boost lasted exactly one game, as the American Giants drew their largest crowd of the season (8,579) on July 9 before the gate returned to its usual dismal figures the following week. Jessup’s long tenure as the American Giants pitcher of the 1940s did not extend into the 1950s; the longtime rotation fixture left for Manitoba and the ManDak League. In his place, Othello Strong led the hurlers while Douglass had an MVP season, according to the Chicago Defender.19 Despite a strong season, the American Giants were denied an opportunity at the pennant because game reports had not been sent to the NAL office; instead, Kansas City was awarded the title.

Welch returned in 1951, but his title expanded beyond manager. Martin sold the club to Welch for $50,000,20 but Welch fronted for Harlem Globetrotters promoter Abe Saperstein. Saperstein’s motive was to position the American Giants to acquire Black players for the St. Louis Browns, who had been recently acquired by Bill Veeck.21 Paige joined the American Giants for a spell before joining the Browns in July.22 By 1952, the NAL was reduced to a six-team circuit and profits from player sales to major-league teams resulted in increasingly modest dividends. The American Giants primarily barnstormed that season, and manager Paul Hardy guided the team to a second-place finish in a four-team tournament that also included Indianapolis, Kansas City, and Philadelphia. That tournament represented the last time the American Giants competed for honors. By April 1953, the American Giants dropped out of the NAL, and the franchise folded shortly thereafter. The Negro American League hung on through 1962, but it did so without the once-proud Chicago American Giants, one of the original great clubs of Black baseball.

JOHN BAUER resides with his wife and two children in Bedford, New Hampshire. By day, he is an attorney specializing in insurance regulatory law and corporate law. By night, he spends many spring and summer evenings cheering for the San Francisco Giants, and many fall and winter evenings reading history. He is a past and ongoing contributor to other SABR and baseball history projects.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following sources:

baseball-reference.com

seamheads.com

Graf, John, ed. From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball (Phoenix: SABR, 2020).

Holway, John B. Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988).

Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball Was White (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970).

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994).

Notes

1 Mark Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues: 1884 to 1955 (Toronto: Citadel Press, 1995), 42.

2 Michael E. Lomax, Black Baseball Entrepreneurs, 1902-1931: The Negro National and Eastern Colored Leagues (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2014), 4; Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing & Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932, (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1994), 32.

3 Larry Lester, Rube Foster in His Time: On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseball’s Greatest Visionary (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2012), 48.

4 Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2007), 37.

5 Debono, 64.

6 Lanctot, Fair Dealing & Clean Playing, 78.

7 Debono, 95-96.

8 Lester, 58.

9 Lomax, 389.

10 Debono, 120.

11 Debono, 121.

12 Lomax: 399.

13 Debono, 125.

14 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 26.

15 Lanctot, Negro League Baseball, 46.

16 Lanctot, Negro League Baseball, 50.

17 Debono, 155.

18 Debono, 170.

19 Debono, 182.

20 Debono, 193.

21 Debono, 93,

22 Debono, 185, 209; Bob Towner, “Hittable but Magical, That’s Satchel Paige,” South Bend Tribune, July 7, 1951, accessed at: https://michianamemory.sjcpl.org/digital/collection/p16827coll14/id/152/.