The Mysteries and Misconceptions Surrounding Conrado Marrero

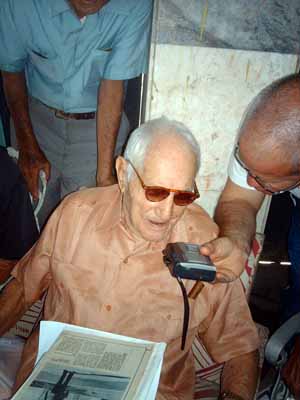

Note: On Wednesday morning, April 23, 2014, Conrado Marrero passed away quietly in his native Havana, Cuba, marking the end to one of the most celebrated and tenacious baseball lives on record. The sad news comes less than two days before the seemingly ageless Cuban legend would have reached his 103rd birthday, extending a remarkable string as MLB’s oldest surviving alumnus and the third longest-lived professional baseball player ever. It is perhaps ironically fitting that the ancient right-hander — a true poet of the baseball twirling art — would depart the earth on the precise anniversary of the death of both Shakespeare and Cervantes. The following article was originally published for Marrero’s 100th birthday in 2011 and seems well worth revisiting again today as apt tribute and memorial to one of the diamond sport’s most indelible and endearing legends. – Peter C. Bjarkman

By Peter C. Bjarkman

Conrado Marrero’s centennial birthday has now arrived with more of a whimper than a shout.

Indeed, the Society for American Baseball Research and www.BaseballdeCuba.com have both headlined the event on their respective websites. But there has been no formal notice from MLB officialdom of this landmark event elevating the colorful fifties-era Washington Senators hurler to the status of big league baseball’s only surviving centenarian.

Such absence of any attention to the senior Cuban ex-ballplayer might strike some as rather odd in light of the sport’s fascination (even obsession) with almost every hidden corner of its celebrated past. Dismissal of Marrero might disarm those of us in the baseball research community, given the intensive efforts of dedicated SABR researchers to educate MLB management about so many overlooked corners of the game’s living heritage.

Of course, Marrero hardly survives today in total obscurity. In his hometown of Havana, the special milestone birth date has been a much-celebrated public event sandwiched between last week’s historic meeting of the Communist Party Congress and this weekend’s opening round of an equally historic Golden Anniversary post-season championship finale. Cuba’s proud baseball community — if not America’s formal baseball establishment — has certainly not let the landmark moment pass without a good measure of pomp and circumstance.

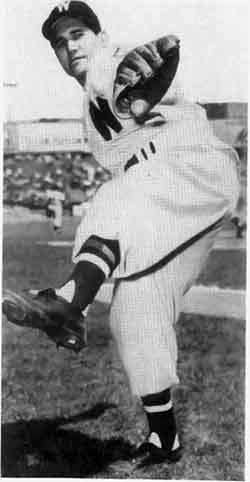

It is indeed mildly surprising that this landmark centennial moment has not drawn even minimal attention in big-league circles. Marrero is now baseball’s only centenarian among former big-leaguers. He is the second-oldest known living veteran of professional baseball (trailing Puerto Rico’s Emilio “Millito” Navarro by five years). For some months now, he has been the senior surviving big-leaguer, and he is not scheduled to be joined in the centenarian ranks for another full year (assuming that 1930s Philadelphia part-timer Ace Parker can hang around until next May). Unlike many of the others who have reached this record for longevity in the past decade or so, Marrero is not exactly a “cup-of-coffee” relic retrieved from the dustbin of baseball history. He was, after all, one of the more colorful figures from a decade many now label nostalgically as baseball’s Golden Age. In 1951, he led his big-league ballclub in pitching victories and earned an American League All-Star Game nomination in the process. That same spring, he also tossed a complete-game one-hitter at the Philadelphia Athletics (marred only by a Barney McCosky fourth-inning round-tripper). Marrero was hardly an accidental big-leaguer.

But in the end, the fact that more stateside notice has not been paid to Conrado Marrero is not so very surprising after all. The American League ballclub for which the colorful Cuban labored for five seasons has been absent from the big-league scene almost as long as Connie Marrero himself. There would be little reason for the National League club now residing in Washington to link Marrero to its own almost nonexistent annals; today’s rather brief Washington ballclub history is wedded to the erstwhile Montreal Expos. The Minnesota AL club that sprung from the carcass of the old Washington Senators has never acknowledged a heritage in the nation’s capital. And of course, there are also issues of Cuban-American Cold War politics and mere logistical inconvenience.

But in the end, the fact that more stateside notice has not been paid to Conrado Marrero is not so very surprising after all. The American League ballclub for which the colorful Cuban labored for five seasons has been absent from the big-league scene almost as long as Connie Marrero himself. There would be little reason for the National League club now residing in Washington to link Marrero to its own almost nonexistent annals; today’s rather brief Washington ballclub history is wedded to the erstwhile Montreal Expos. The Minnesota AL club that sprung from the carcass of the old Washington Senators has never acknowledged a heritage in the nation’s capital. And of course, there are also issues of Cuban-American Cold War politics and mere logistical inconvenience.

Marrero fell from the big-league radar screen years ago when he elected to remain in Havana rather than flee an on-going socialist upheaval that so changed life in his native land. If, like so many of his former mid-century Cuban ball-playing compatriots, he had exiled himself to Miami he might well have been a frequent guest over the years at old-timers festivities staged in big-league parks. And yet by becoming a bit more of a dim baseball memory in Miami, Marrero assuredly would also have become far less of a true baseball icon back home in Havana.

What surprises and even disheartens this writer on Conrado Marrero’s special day is not the scant attention paid by North American fans to his milestone longevity. The saddest element is instead the realization that so little is actually understood about the true scope and meaning of Marrero’s marvelous career. Greater acknowledgement on this particular date of Marrero’s status as “oldest living big-leaguer” might at day’s end seem even more unwelcome than continued obscurity. It certainly would have signaled a notable distortion of Marrero’s remarkable multi-decade diamond achievements. Those few years spent by the charismatic right-hander on American League turf in Washington might be viewed by many as a career pinnacle. It is, after all, part of our universally shared myopia about the national pastime to assume corporate Major League Baseball’s realm is the true yin and yang of our bat and ball sport. (Note that basketball does not automatically mean the NBA; nor football the NFL; nor hockey the NHL. But somehow the mere mention of baseball is always meant to conjure up MLB.) What then could be more important in the life of any baseball player than to set foot inside a big-league locker room or trod on a big-league ballpark diamond? What baseball career has ever reached ultimate achievement without at least a brief major league experience?

But is major league achievement truly to be taken as the single legitimate measure or even the primary yardstick for baseball accomplishment? There are assuredly many past-era ball-playing heroes in Japan or Venezuela or Mexico or Cuba — athletes who never reached big-league rosters — who would not entirely agree with such commonplace stateside provincialism equating the notion “baseball” solely with the North American professional version of the game. And what about that multitude of veteran blackball stars who late in life were repeatedly so outspokenly proud of careers in an alternative baseball universe; why were so few of them either depressed or downtrodden by social forces that kept them outside the exclusive circle that was major league baseball? Was “baseball” to them something only legitimized by the top all-white ballclubs?

If there is any ballplayer who exemplifies the expansiveness of a baseball universe outside the realms of corporate major league baseball, it is Conrado Marrero. Those seasons spent with Clark Griffith’s lackluster Senators represent more of a footnote than a coda to Marrero’s complex resume. As proud as he may have been of his stint in the majors, he was never defined by the brief span that came only well after he had reached his prime as a stellar pitcher. To celebrate Marrero’s sparse tenure on a big-league stage while remaining ignorant of the rest of the package is far more of a gaff than any failure to adequately acknowledge those Washington years.

Recently I wrote elsewhere that Cuba’s baseball hierarchy has gone out of its way in past months to celebrate Conrado Marrero as a fitting linkage between two distinct but not unrelated baseball epochs. I even claimed in my Havana Times essay that Havana’s annual homage to Marrero in recent years clearly gave the lie to all those frequent stateside claims about Cuba (especially the INDER sports ministry) abandoning all ties with a pre-revolutionary pro baseball heritage. But this claim is perhaps too simply stated and far too easily misconstrued. It definitely needs some further clarification.

Recently I wrote elsewhere that Cuba’s baseball hierarchy has gone out of its way in past months to celebrate Conrado Marrero as a fitting linkage between two distinct but not unrelated baseball epochs. I even claimed in my Havana Times essay that Havana’s annual homage to Marrero in recent years clearly gave the lie to all those frequent stateside claims about Cuba (especially the INDER sports ministry) abandoning all ties with a pre-revolutionary pro baseball heritage. But this claim is perhaps too simply stated and far too easily misconstrued. It definitely needs some further clarification.

Neither the Cuban media nor Cuban League officials have focused on acknowledging Marrero as the oldest surviving big-leaguer — although that connection is prominently mentioned in two current articles posted on official league websites. Cuba’s baseball management of course has no direct commerce with the majors and little enough traffic with other professional circuits. While the handful of Cuban “defectors” are not any longer entirely deleted from official mention, still there is no coverage of big-league games anywhere on the island. Marrero’s earlier ties with professional baseball are hardly taboo but rather are simply not the focus of a Cuban baseball universe with far different traditions to celebrate. Marrero is repeatedly (and appropriately) lionized as a symbol of Cuba’s own unique baseball reality which is still now and always has been largely a tradition rooted in the amateur versions of the sport. Yes, there was a thriving pro circuit on the island before the communist takeover, but it was a circuit restricted to a handful of teams lodged in the capital city of Havana. Nostalgic Cuban exile literature has in recent decades painted the pre-revolution Havana winter circuit (often a dysfunctional league teetering on the verge of economic collapse) as something far more grandiose than it actually was.

The soul of the island-wide sport was sugar mill baseball and the flourishing amateur squads that spawned many of the island’s top stars. Amateur clubs from a WW II-era AAU circuit that often numbering more than thirty teams also provided the backbone of a national team capable of dominating early international tournament play two full decades before the appearance of Fidel Castro. It is true enough that a dozen winters before the 1959 revolution Marrero’s reputation at home had already been linked to play with the professionals — but only after the crafty hurler had already become a living legend and a true national hero on the fields of amateur play. Marrero’s greatest moments came with the forties-era Amateur Athletic Union circuit and with a national squad hosting the first string of Amateur World Series events in the shadows of a Second World War. With his titanic struggles versus the Venezuelans at Tropical Stadium in the early forties, Connie Marrero singlehandedly launched a still-unrivaled tradition of international tournament domination that down to the present has remained the true pride of the Cuban national sport. His October 1942 three-hit victory over a reigning Venezuelan world championship squad (featuring the father of future Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio) set off island-wide celebrations of a kind never witnessed by the Havana-based professional circuit of the same era.

Even when Marrero turned to professional baseball in the mid-forties (after his amateur league suspension for moonlighting with a second ballclub), his greatest triumphs came while wearing the uniform of the Havana Cubans — the island nation’s first venture into organized baseball — and not while donning an American League jersey in Washington. Earlier he had been the only island pitcher to toss a pair of no-hitters in the AAU amateur circuit. In his first three pro seasons with the Havana entry in the Class B Florida International League his control was outstanding enough to strike out 586 while walking only 117. He became the first Cuban ever to defeat the USA in world amateur play (during an inaugural 1939 IBAF world championship round-robin staged in Havana). Despite the later substantial big-league cup of coffee, the hydrant-shaped junk-ball pitcher would still claim during his tenth decade that his fondest moments and most stellar achievements came with his first team in Cienfuegos as a rank amateur.

After the 1959 revolution, Marrero elected to throw his lot with newly emerging baseball realities on his native island. He was one of the very few who did so — most of his surviving former rivals and teammates would live out their final years in stateside exile. He worked tirelessly to build up new baseball traditions within his homeland, still serving as a part-time pitching instructor for the Granma Province Cuban League ballclub well in his late eighties. One Marrero protégé was current Granma ace Ciro Silvino Licea. At age 87 he also had a small hand in developing current island slugging star Alfredo Despaigne. It was this labor of the past half-century that made him far more than a retired cup-of-coffee big-leaguer living with only fleeting dreams of a distant and faded past. Marrero’s intimate and active links with the game reached well into his nineties.

Mystery and misconception have always surrounded the island nation’s greatest baseball icons. That layer of dense mystery is not only a recent product of Cuba’s post-revolution Cold War-era isolation from the North American baseball scene. Rather it stretches back to the first half of the previous century when Cuba’s celebrated “beisbol paradiso” was so often mistakenly painted as a racial paradise — a prejudice-free alternative universe where whites and blacks played side-by-side free from the odious “gentleman’s agreement” that tainted North American leagues. The reality was of course somewhat different than the celebrated myth. Cuba’s wintertime pro ball circuit was indeed integrated after 1900, but many of the island’s more elite athletes — Marrero included — performed in a “white-only” segregated amateur circuit that was the island’s true diamond showcase. (Any talented white player could actually earn a far better living with industry-sponsored AAU clubs, where a roster spot was accompanied by a plush company job with few responsibilities attached, and where league games were strictly weekend affairs.) The impenetrable racial barriers of major league baseball kept lower-class and dusky-skinned greats like Dihigo and Méndez and Champion Mesa hidden from the North American limelight. And those few, like Adolfo Luque, who were white enough to sneak past the racial ban up North inevitably suffered a somewhat different fate that equally diminished big-league careers.

There is little room to dispute that Luque was the greatest white Latino ball player during the first half of the last century — without doubt the top Latino big-leaguer. He was the first of his Caribbean countrymen to pitch and win a World Series game (1919), to rack up 100 big league victories, to pace the majors in single-season wins, shutouts and ERA (27-8, 6, and 1.93 with Cincinnati in 1923). He still holds the Cincinnati franchise record for single-season victories more than a half-century after his passing. Until the three-quarter mark of the 20th century he was the pacesetters in career victories among all Latino hurlers (falling just short of 200). In brief, Luque “enjoyed” what was arguably a Cooperstown Hall of Fame career. But popular stereotypes always overpowered and overshadowed any noteworthy diamond achievements in Dolf Luque’s case. There were all those embellished anecdotes about an uncontrollable “Latin temper” and reports (few substantiated) of numerous unsavory bellicose acts — especially the largely apocryphal tale about charging off the mound and slugging a verbose Casey Stengel in the New York Giants dugout. If there remains a big-league Cuban legend that is most tragically and unjustly forgotten, then it is most likely Luque and not Marrero.

Cuba’s iconic revolutionary leader — Fidel Castro himself — was tied more closely to baseball than any other world political figure. Certainly no head of state has ever figured so prominently and for so long a span of time in the fortunes of his people’s national game. But once again the outsized legend and impenetrable mystery has always clouded over the factual realities. Fidel was never a genuine baseball prospect and was thus never pursued by a handful of professional scouts back in the 1940s as popular myth would have us believe. The legend emerged of course from the irresistible notion that Cold War politics might have been so very different if only Cuba’s “supreme leader” had been tossing fastballs toward American League batters visiting Washington’s Griffith Stadium, instead of tossing curveballs at Washington politicians residing on Capitol Hill. The legend of “Fidel the pitcher” sprung from a fictionalized account spun by former big leaguer Don Hoak in the pages of Sport magazine (June 1964); it was fertilized by numerous photos of the new Cuban leader lobbing pitches in a staged 1959 exhibition tune-up before an International League contest in Habana (July 1959); it has remained a tale dismissed with laughter on the streets of Havana.1 But if Fidel was never a baseball pitcher, he nonetheless did play a huge role in building Cuba’s legendary baseball successes of the past half-century. The outlawing of professional sport and introduction of a new-style island-wide amateur league — all coming under Castro-inspired social reforms of the early sixties — opened the door on a new era of diamond expansion that would soon elevate Cuban baseball to an international status never achieved in pre-revolution decades.

When it comes to pre-1947 Cuban blackball stars, the story is pretty much the same. Martín Dihigo has long been ranked supreme among all past-era island stars, yet most North American fans know preciously little about the 1977 Cooperstown inductee. It is often reported that Dihigo remains the only athlete enshrined in four national halls of fame (it is actually three) and that “El Inmortal” was a true standout at all nine diamond positions (he starred on the mound and in the infield and outfield yet rarely if ever appeared behind the plate). Worse yet are the all-too-easy substitutions of quaint legend for documented fact in the cases of recent Cooperstown honorees Cristóbal Torriente and José de la Caridad Méndez. Méndez was an acknowledged blackball star who drew most notice (especially from historians writing a half-century after his premature death) for a string of headline performances against barnstorming big leaguers. Much ink has been devoted to a November 1908 Méndez one-hitter tossed against a squad of vacationing Cincinnati Reds. But it remains a challenge to cut the hyperbolic chaff from the visible wheat.

Méndez was indeed a terror to winter league batters for a few short seasons (1908-14) before prematurely ruining his golden arm; he did once rack up 45 consecutive scoreless innings against various clubs defined by often suspect talent and sometimes even more suspect on-field efforts. But was he a legitimate Hall of Famer, or perhaps more the beneficiary of a huge latter-day “feel good” sympathy vote from a Cooperstown veterans committee dedicated to belatedly correctly past-era racial wrongs? The triumphs on which the bulk of the Méndez legend rest were all exhibitions against touring big-leaguers who might well have expended questionable effort in games that counted for little more than pride. And it is undeniable that his career on the mound fell far short of the ten-year standard for Cooperstown eligibility long applied to all true big leaguers. “The Black Diamond” most assuredly did log several rather remarkable campaigns, but it is hard to deny that much of his success came against far less than stellar competition. His biggest boast for Cooperstown status seemed to come from rich descriptions of his pitching style by former rivals (octogenarians repeating dim memories from games played a half-century earlier) or from modern-era historians embellishing such word-of-mouth reports. Méndez may indeed have been Cuba’s earliest unrivaled pitching phenomenon, but there is little beyond hearsay to document a true Cooperstown pedigree.

The same might be asked of Torriente — where is the solid evidence for true Hall of Fame status? There are numerous anecdotes detailing titanic power hitting and brave fly chasing yet very few surviving statistical records to back up the Torriente legend. We know that he hit .352 (with some numbers missing) in a dozen very short Havana winter seasons (about half of them less than 30 games); we also know that about two dozen sluggers now reach those numbers in a modern-era 90-game Cuban circuit that is by every reasonable measure of much higher quality. Torriente’s present fame is preserved largely by word of mouth, mostly in tales that amplify with each retelling. The most egregious anecdote involves an exhibition in which he outslugged Babe Ruth during a 1920 Havana winter tour. But historian Roberto González Echevarria, among others, long ago exposed that game for what it truly was — the New York Giant players took the field after a night of heavy drinking, used a first baseman as their pitcher, and made little effort to track down Torriente’s three fly balls (struck against infielder High Pockets Kelly) that resulted in highly suspect inside-the-park round-trippers. Cuban journalist Ramón Mendoza wrote at the time that “the game was like a batting practice session for Almendares because the Giants did not seem too focused on winning.” Full airing of these arguments about Torriente and Méndez are of course best left for elsewhere. But certain illustrative facts nonetheless can be stressed here. Méndez pitched for only a few top seasons and his greatest triumphs game in contests that may have not been altogether legitimate. And Torriente’s fame rests more than anything else on a staged game that was in the end a pure sham. The true facts about this pair of Cuban Hall of Famers — like so much else in the island’s baseball heritage — are forever clouded in opaque mystery and a good deal of inflated misinformation.

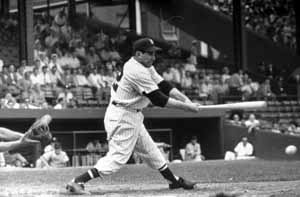

Marrero’s own truncated career in Washington (like that of Méndez and Torriente on the winter ball circuit) is now all too often seen through the distorting rose-tinted glasses of nostalgia. Those who remember him as a Washington Senator most often remark on the apparent miracle of pitching so well as a 40-year-old big-leaguer. But that was not at all how he was celebrated at the time in mid-century Washington. Instead Marrero was painted time and again with the same generic stereotypes that plagued fellow countryman Luque before him. Those stories most widely circulated focused on an unorthodox style (“his windup looked like a cross between a windmill gone berserk and a mallard duck trying to fly backwards”), or fabricated anecdotes about Ted Williams mocking an innocent locker room autograph request, or perhaps the old standby with all Latino ballplayers — those seemingly silly sounding statements to the press (“Deezy Dean, he good peetcher … he peetch too much … Me rest plenty … Me still peetch.) And Marrero was never called Conrado by Washington scribes but always referred to by the somewhat emasculating moniker “Connie.” No one wrote about him that way in Havana.

It is into this regrettable longstanding tradition of misconceptions and confusions surrounding Cuba’s legitimate baseball history that Marrero himself now so often falls. Marrero’s career zenith was not those years spent in Washington — his legacy is built on far more than merely outliving all but a handful of those who set foot (often only very briefly) on big league diamonds. To see him only as the oldest surviving big leaguer is more to diminish than adequately celebrate his extensive career. A truly representative image of Connie Marrero would more justly have him adorned with a patriotic Cuban national team uniform (this is indeed his portrait on the mural inside the foyer of Latin American Stadium — one that looms over the busts of Martín Dihigo and Adolfo Luque) and not a Washington American League jersey. The tales of diamond exploits by which we best recall him today should most fittingly be those of legendary battles with Daniel Canónico and not quaint anecdotes about Ted Williams mocking the cocky Cuban for requesting his autograph on a strikeout ball.2 Or perhaps his lasting image should be draped in the uniform of the Class AA level Havana Cubans (where he pitched more than 250 innings for each of three seasons while never registering an ERA mark above 1.67) or even the winter league Almendares Alacranes (where he struck out 478 and only walked 295 during a full decade of service).3 Marrero’s legacy was always largest in his homeland where he remained simply “the best there was” and not on foreign soil where he was most often painted in the press as something akin to a loveable cigar puffing caricature.

Some might find it unjust that big-league fans ignore Marrero’s centennial while Cuban officials generously celebrate his baseball life with their annual ceremonies in Latin American Stadium or with such public accolades as dedication of the recent showcase Golden Anniversary All-Star Game. But I am not among the group that mourns. Instead, I find this failure to celebrate Marrero primarily for his brief and only mildly successful sojourn among the top pros to be something of a relief. Don’t get me wrong here — reaching the North American big leagues is a marvelous achievement, and outliving all others who tasted such rare success is perhaps more noteworthy still. But to celebrate Marrero mainly as a colorful if short-tenured big leaguer seems almost parallel to recalling Bobby Thomson as the longest-tenured big leaguer accidentally born in Scotland. It is akin to hanging Don Larsen’s fame on the sole fact that he was once a central figure in one of the most celebrated multi-player swaps in big-league annals. It makes about as much sense as immortalizing Fred Merkle for a single base-running gaff rather than as one of the most brilliant fielders and batsmen of his era. It all widely misses the point. It only reminds us of that pithy rejoinder from baseball’s greatest catcher-turned-philosopher — “You must be careful not to believe everything you think.”

Taken in proper perspective, Connie Marrero’s big-league sojourn was but a small corner or brief interlude in a much grander and more achievement-stuff baseball journey. His greatest baseball moments were not those enacted on the American League diamonds of the early fifties; instead those most cherished moments were all played out on the amateur diamonds of WWII-era Cuba. A whole nation cheered when he overmatched rival Daniel Canónico and Team Venezuela in October 1942 and thus returned a coveted Amateur World Series title to Cuban soil. Only Dolf Luque’s two World Series triumphs (1919 and 1933) had ever previously witnessed a Cuban hurler bagging a bigger victory. If anything, after all, it was in the “big time” — in the still stereotype-plagued if now racially open major leagues of the early fifties — where Marrero was most mistreated, abused and certainly misunderstood. Like Luque and so many other Latino ballplayers of the early and mid-century years he was relentlessly dismissed as a convenient stereotype. He was most celebrated for his oddness and not his diamond mastery. It was the stories surrounding Marrero’s clubhouse antics and not his numerical pitching lines that always seemed to reach legendary proportions. The lasting image for most stateside fans remained the one capsulated in a series of 1951 and 1952 magazine photos (Connie puffing his cigar, studying an English lexicon, or demonstrating an odd-looking windup) placed alongside accompanying stories that always defined the paunchy Washington right-hander as a kind of carefree Cuban goodwill ambassador to the thriving “Golden Fifties” era big league scene. Such after all were the times. It was never quite that way back home where he remained always a true hero of the diamond — masterful with his pitching artistry and not merely “colorful” with his broken English and oversized stick of Cuban tobacco.

For those many fans who believe the sport begins and ends with the antics of the American and National Leagues, it could not possibly be appreciated that Marrero’s big league stopover was only icing on an already substantial cake. The 39-year-old “rookie” (a misnomer if there ever was one) had long been a legend in his homeland before he ever set foot in Las Grandes Ligas. And his seemingly endless baseball sojourn would turn perhaps even more remarkable — another half-decade of efficient professional hurling followed by a full half-century of training young prospects for a national team that became the scourge of international competitions — once he returned to his native island a handful of years before Fidel Castro’s revolution sent Cuban baseball hurtling toward the dark side of the moon.

So I for one rejoice that Marrero’s true legacy is now celebrated most ostentatiously precisely where it was firmly built and always best understood — in his baseball-loving Cuban homeland, in a place where baseball still remains a true “national pastime” and not merely one of numerous competing commercial sporting spectacles.

Let me repeat here what I once wrote elsewhere, because it now has such resounding relevance on this very day (April 25, 2011) when Conrado Marrero crosses the threshold into his second century. The stogie, the thick Spanish accent, and the elaborate windmill windup were trademark realities that quickly merged rapidly into all-too-familiar stereotypes. In the large scheme of things Conrado Marrero was little more than a blip on the radar screen of baseball’s Golden Age Fifties so dominated by names like Mantle, Musial, Williams, Spahn, Mays and Banks. But from yet another perspective, the American League Washington Senators and the whole enterprise of big league baseball were themselves, in turn, but a mere blip in the baseball-playing career of the seemingly ageless and remarkably durable Conrado Marrero.

PETER C. BJARKMAN is author of “A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006” (McFarland, 2007) and is widely recognized as a leading authority on Cuban baseball, both past and present. He has reported on Cuban League action and the Cuban national team for www.BaseballdeCuba.com during the past four years and is currently completing a book on the history of the post-revolution Cuban national team.

Notes

1 A full chapter of my volume A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (2007) is devoted to dismantling the popular legend of Fidel Castro as baseball prospect and explicating the role that “El Jefe” actually did play in the development of post-1960 Cuban League baseball. Fidel was indeed noted for youthful athletic prowess (mainly in swimming and basketball), and it was as a basketball player that he was named Havana’s 1944 High School Athlete of the Year.

2 The Ted Williams autograph story (one reported in my earlier Baseball Biography Project portrait of Marrero) perhaps best illustrates some of the nonsense surrounding Marrero’s big-league adventures. The event has Marrero asking Williams for a signature on a ball with which he earlier struck out the Boston slugger. Williams supposedly later returned the favor: that very afternoon he reputedly crushed a homer off the Cuban and while rounding the bases taunted Marrero by yelling “Why don’t you retrieve that one and I’ll sign it for you too!” It is only one such story picturing Marrero as a trickster often befuddled by his own antics. The problem of course is that it almost certainly never happened. Marrero first repeated and then denied the account in one of my earliest discussions with him in Havana. The irresistible nature of the quaint legend is suggested by the fact that it has often been attached to other Latino hurlers with the design of emphasizing an all-too-familiar stereotype. One version replaces Williams and Marrero with Mickey Mantle and Pete Ramos. The story is akin to the even more widely circulated one involving Fidel Castro’s prowess as a youthful pitching prospect. I once wrote to Bob Costas during the 1998 World Series after Costas had repeated the “Fidel was scouted heavily by the Senators, Yankees and Giants” legend several times during that particular Series, apparently motivated by the MVP performance that year of Cuban defector Orlando Hernández. I suggested that if Costas was intent on spreading the long-debunked myth he might at least stress the fairy tale quality of such a baseless legend. Costas did eventually write back to thank me for clarifying that nonsense about Fidel as a talented pitcher, but also to remind me that the story was just too darn good for him ever to desist from using it.

3 It is truly ironic that while the Cuban winter league record of José Méndez (posted in a far less robust era) was a large part of the legacy earning “The Cuban Black Diamond” an eventual plaque in Cooperstown, Marrero’s own quite parallel career ledger in Havana with Almendares is rarely emphasized when assessing the merits of “El Guajiro de Labertino” (“The Labertino Peasant”). While Méndez is celebrated for owning the Cuban winter circuit record for winning percentage (76-28, .732), 61 of those victories came over a mere half-dozen campaigns during which Méndez was a regular on the mound (before he eventually damaged his arm). Marrero also hurled 13 winters with Almendares (the same club that employed Méndez four decades earlier) and chalked up a very similar 69-46 mark in what is widely acknowledged as a far less pitcher-friendly epoch than the Méndez “dead ball” era.