‘We Are the Ship, All Else the Sea’: The Founding of the Negro National League

This article was originally published in “The First Negro League Champion: The 1920 Chicago American Giants” (SABR, 2022).

As witnessed during commemorations in 2020 celebrating a century of Negro League baseball, the foundation of the Negro National League in 1920 provides a generally accepted starting point for Black baseball’s league era. Black baseball, through the experience of Black ballplayers and the establishment of clubs that became institutions, already had a history that stretched decades back into the nineteenth century. Also, while 1920 may have been the watershed year in the establishment of a league of Black ballclubs, the idea of creating such a league among top Black clubs was not new; and those efforts also formed part of the prehistory of Negro League baseball.

As witnessed during commemorations in 2020 celebrating a century of Negro League baseball, the foundation of the Negro National League in 1920 provides a generally accepted starting point for Black baseball’s league era. Black baseball, through the experience of Black ballplayers and the establishment of clubs that became institutions, already had a history that stretched decades back into the nineteenth century. Also, while 1920 may have been the watershed year in the establishment of a league of Black ballclubs, the idea of creating such a league among top Black clubs was not new; and those efforts also formed part of the prehistory of Negro League baseball.

There had been an effort as early as 1886 to organize the Southern League of Colored Base Ballists, which was followed up by an 1887 attempt to organize the League of Colored Base Ball Clubs among teams in the East and Midwest.1 Neither effort gained much traction. The top Black clubs of the time, such as the Cuban Giants, may have found barnstorming to be more profitable. The next serious effort to organize a league was almost two decades later. An Eastern circuit of six clubs dubbed the International League of Colored Baseball Clubs in America and Cuba (ILBCAC), led by Walter Schlichter and his then-dominant Philadelphia Giants, materialized in early 1906.

That effort morphed into another effort by Schlichter and other power brokers (many of whom, like Schlichter, were White) in Eastern Black baseball to form a league in October of that year. Schlichter and promoters John Connor and Nat Strong backed plans to form the National Association of Colored Baseball Clubs of the United States and Cuba (NACBC) on a model similar to the American and National Leagues.2 The NACBC, however, would come to operate very differently, acting more like as a booking agent for Eastern and Midwestern clubs than as a traditional baseball league.3

Chicago’s Frank Leland, owner of the Midwestern powerhouse Leland Giants, was part of an effort in 1907 to create a professional league among interested Midwestern cities. The National Colored Baseball League was the product of a meeting in Indianapolis in December 1907; however, the league quickly fell apart and never played a game. Recognizing the counterproductive effects of player raiding and contract jumping, attorney Beauregard Mosely of the Leland Giants led an effort in 1910 to bring together the leading clubs of the Midwest and South. Mosely published a 17-point manifesto that addressed governance, admission prices, transportation costs, and player salaries, among many topics.4 Eight clubs were represented at an organizational meeting in Chicago in December 1910, but only a few had credible financial backing.5 The product of that meeting, the Negro National Baseball League of America, also collapsed as quickly as it formed; travel costs were deemed too great to permit the clubs to be profitable.6

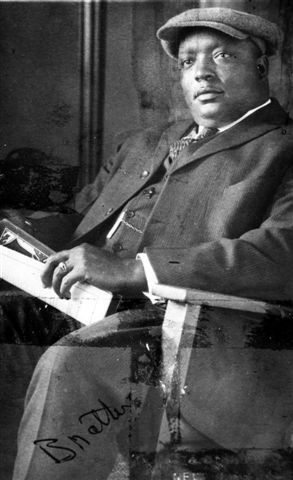

Led by Rube Foster, the Chicago American Giants were born from a split with the Leland Giants to become the elite club of the 1910s. The American Giants profited from a combination of barnstorming through the West and South, while arranging “championship” series against the leading clubs of the East and Midwest. Foster became a powerful voice for organizing Black baseball similarly to the major leagues throughout the decade. Penning articles in Black newspapers including the Chicago Defender and Indianapolis Freeman, Foster pressed the case that better organization would improve the legitimacy and public perception of Black baseball.

In January 1917, player-turned-sportswriter Sol White joined with others in announcing intentions to form a Negro Baseball League; that effort also failed, primarily through the disruptions caused by World War I. The war was perhaps an unlikely contributor to the eventual formation of the Negro National League. Factories in Northern cities required labor to build the machines that would propel America and her allies to victory. The Great Migration witnessed the emigration of millions of Southern Blacks to the cities of the Northeast and Midwest. In Chicago, the Black population more than doubled between 1910 and 1920, growing from 44,000 to 110,000.7 The Black populations of other Northern cities also swelled, increasing the potential audience for Black ballclubs. Sol White would again be active after the war, outlining plans for an effective and compact circuit comprising established teams with home ballparks and traveling teams that would float among stadiums.

Following on White’s work, momentum increased for an organized Black league in late 1919. With the war over and clubs such as the American Giants coming off financially successful seasons, the timing seemed right. Sports journalist Carey B. Lewis, writing in the Chicago Defender, predicted a Midwestern league run by Black entrepreneurs for the 1920 season.

Foster, who was never shy about expressing his views on the state of Black baseball and the need to organize, offered detailed opinions in a series of articles that appeared in the Chicago Defender between November 1919 and January 1920. Foster focused on the “Pitfalls of Baseball,” many of which were exacerbated by the lack of organization within the Black game. Foster commented on scheduling, leadership, business judgment, player defections, and stadium availability. He urged other Black baseball magnates to set aside past differences and create an effective structure. “We cannot get along without an organization,” Foster wrote.8

Foster, who was never shy about expressing his views on the state of Black baseball and the need to organize, offered detailed opinions in a series of articles that appeared in the Chicago Defender between November 1919 and January 1920. Foster focused on the “Pitfalls of Baseball,” many of which were exacerbated by the lack of organization within the Black game. Foster commented on scheduling, leadership, business judgment, player defections, and stadium availability. He urged other Black baseball magnates to set aside past differences and create an effective structure. “We cannot get along without an organization,” Foster wrote.8

In his final article, he proposed a national association of Western and Eastern circuits culminating in the championship series, but noted the previous failure of such expansive efforts.9 Nonetheless, Foster announced a meeting to be held in Kansas City in February 1920 with the goal of organizing a league that proved predominantly Midwestern.

Foster’s proposal received “cautious support” from Indianapolis ABCs manager C.I. Taylor and sportswriter Dave Wyatt in subsequent issues of The Competitor.10 As Taylor stated, “We have the goods, but we haven’t the organization to deliver them.”11 Foster and Taylor had feuded during an intense rivalry between their clubs in the mid-1910s as Taylor claimed Foster rebuffed his earlier suggestions to organize a league.12 Now, the two rivals appeared to share the same vision. Wyatt expressed concerns that demand for talent outweighed the supply, and it would be challenging to maintain competitive balance within an eight-team league.13 Foster worked to set the foundation for a successful meeting in Kansas City, traveling to recruit principally the owners of Midwestern clubs in an effort to complete a circuit. In the specific case of Kansas City, Foster sided with White promoter J.L. Wilkinson over local Black businessmen as Wilkinson converted his All Nations team into the Kansas City Monarchs. Wilkinson crucially had access to the ballpark where the American Association Blues played their games. Foster also courted Eastern clubs, including Ed Bolden and the Hilldale club outside of Philadelphia, but those efforts did not reap immediate dividends.14

Indeed, an organizational meeting of Midwestern teams was held at the Paseo YMCA and Street’s Hotel in Kansas City on February 13 and 14, 1920. The clubs and representatives in attendance were: Chicago American Giants, Rube Foster; Chicago Giants, Joe Green; Detroit Stars, Tenny Blount; Indianapolis ABCs, C.I. Taylor; Kansas City Monarchs, J.L. Wilkinson; and St. Louis Giants, Lorenzo Cobb. Although not present, the Cuban Stars and Dayton Marcos rounded out the league. Cuban Stars owner Abe Molina voiced support for the effort and gave Foster his proxy for the meeting.15 Dayton Marcos owner John Matthews is listed as an attendee in some reports but it appears that the flu kept him in Ohio. Foster came prepared to the meeting, and he created a mild surprise when he presented the delegates with drafts of the corporate charter and articles of incorporation for the new league. Versions of the latter had already been filed in several states where the league would operate and several where it would not.16

In addition to the clubs represented at the meeting, several sportswriters were present, not just to report on the events but to play an active role in the league’s proceedings. In fact, Lewis, Elwood Knox of the Indianapolis Freeman, and Charles Marshall and Dave Wyatt of the Indianapolis Ledger were joined by attorney Elisha Scott, from nearby Topeka, Kansas, in drafting the league’s constitution. Scott served as the lead drafter for the governing documents. In the constitution, the league was officially known as the National Association of Colored Professional Base Ball Clubs, but Negro National League became the standard reference to the new circuit. To sign on formally, the clubs agreed to pay a $500 deposit, respect contracts, and play a schedule of league matches.

In order to facilitate competitive balance, some players were transferred between clubs. This process was overseen by the sportswriters, and several impact players changed hands. Oscar Charleston, who joined Chicago in 1919, returned to Indianapolis, where he played previously from 1915 to 1918. Sam Crawford, who spent most of his career in Chicago but played for Detroit in 1919, was sent to Kansas City, along with former All-Nations players and fellow pitchers Jose Mendez and John Donaldson. Pitcher-outfielder Jimmie Lyons transferred from St. Louis to Detroit, although he would land in Chicago the following season.

Foster was named league president and secretary, a role that set up potential conflicts of interest between his league office and his roles of owner and manager of a member club. St. Louis club official W.E. Ferance pointed out the absurdity of complaints about Foster the manager, being sent to Foster the secretary, to be ruled on by Foster the president. Another source of criticism concerned the provision that Foster’s booking agency received a fee for all games. Clubs were committed to the 5 percent assessment, which meant Foster pocketed 10 percent of every gate; owners grumbled about this throughout Foster’s presidency. The league treasury also received 10 percent of all receipts, which, when combined with rental fees and visiting club guarantees, took a significant bite into profitability in this and future seasons. Foster would also receive criticism for engineering the league schedule to ensure that a greater proportion of lucrative weekend games were played at Schorling Park.

The NNL initially intended to commence operations in 1921 in order to allow clubs enough time to secure playing facilities. Only a handful of clubs, including Chicago, Indianapolis, and Kansas City, had stable ballpark arrangements. Nonetheless, adapting a quote from Frederick Douglass, the league embraced the motto, “We Are the Ship, All Else the Sea,” and announced in late February its intent to start play in 1920. Ballpark availability indeed had an effect on scheduling arrangements, particularly with the Chicago Giants and Cuban Stars operating exclusively as traveling teams. As a result, the NNL had an unbalanced scheduling format and also permitted the scheduling of games against nonleague competition to boost gate receipts.

The first recognized NNL game was played on May 2, 1920 with the Chicago Giants visiting the ABCs at Indianapolis’s Washington Park. Behind Ed “Huck” Rile’s pitching, the ABCs claimed a 4-2 victory before 8,000 fans. The ABCs appeared likely to be one of the contending teams for the NNL pennant. Not only was Oscar Charleston back in town, the team had maintained key pieces from a roster that challenged the American Giants for championships in the mid-1910s. First baseman Ben Taylor (one of several brothers whom C.I. Taylor would manage) and left fielder George Shively provided punch to a formidable lineup. In addition to Rile, Dizzy Dizmukes and Dicta Johnson remained pitching holdovers from prior championship teams. Dismukes and Johnson would make up the innings lost when Rile jumped his contract in midseason for the Eastern Lincoln Giants.

The formation of the NNL did not resolve all of the issues that impeded league formation in the past, and challenges remained apparent throughout the season. Despite efforts at player redistribution, competitive balance proved to be an issue. The Chicago Giants suffered from their status as a traveling team; records credit the team with only five league wins out of 36 games; the Giants logged only about half as many league games as other NNL clubs. The offense ranked near the bottom of the league although veteran outfielders Frank Duncan and Horace Jenkins (formerly of the American Giants) and third baseman Willie Green led the lineup. Nineteen-year-old catcher (also named) Frank Duncan and 20-year-old shortstop John Beckwith were at the beginning of what proved to be long Negro League careers, but neither could help the Giants avoid the cellar. The pitching was the league’s worst by most measures, with John Taylor throwing generally solid innings for which his won-lost record did him no justice; the rest of the staff was subpar, including a now-fading Walter Ball, who was winless in his NNL starts.

Along with the Giants, the Dayton Marcos were also overmatched. Candy Jim Taylor was near the start of a managerial career that featured three Black baseball championships, but his Marcos were a seventh-place team. Though 36 years old, Taylor also served as the regular third baseman and still had enough spring in his step to steal a fair number of bases. Left fielder Koke Alexander was the only regular who produced offensively on a consistent basis. Similar to Taylor in Chicago, George Britt proved an effective starter among a staff otherwise lacking; his career would see better days in coming years with the Homestead Grays.

The Cuban Stars featured a lineup of four future Cuban Hall of Fame inductees, including manager Tinti Molina. Outfielders Valentin Dreke and Bernardo Baro, also future inductees, supplied the most significant contributions from an otherwise weak-hitting squad. Pitchers Jose Leblanc, Cheo Hernandez, and Faustino Valdes threw all but a handful of innings; their collective effectiveness ranked near of the top of the NNL and helped the club eke out a winning record at 35-34, which was good enough for fifth place.

The American Giants raced out to a commanding position, winning 32 of their first 37 games.17 This achievement may not have been apparent to fans, as the NNL failed to produce standings, box scores, or batting and pitching statistics that might have enhanced interest. Foster’s team had been expected to be challenged by the aforementioned Indianapolis ABCs as well as St. Louis, Detroit, and Kansas City.

The St. Louis Giants, however, struggled during the campaign. Young pitchers Bill Drake and Wayne Carr joined veteran John Finner in throwing most of the innings, but their production was average at best. Deprived of Lyons through the preseason player reshuffling, the offense proved similarly average. While they lacked pop, these Giants definitely had speed with second baseman Lee Hill and outfielder Charlie Blackwell among the most active NNL players on the basepaths. Ultimately, player-manager Dick Wallace led St. Louis to a 32-40 record and a sixth-place finish.

Indianapolis joined Kansas City and Detroit among the chasing pack after the American Giants stormed through the first half of the league schedule. The ABCs wound up in fourth with a record of 44-38-4. Wilkinson built a formidable challenger from the remnants of the All Nations team. The acquisitions Crawford, Mendez, and Donaldson hurled key innings for the Monarchs, especially when combined with innings-leader Rube Curry and future Hall of Famer Bullet Rogan; Rogan was just getting started in dominating the mound through the 1920s.

Rogan, Donaldson, and Mendez also contributed beyond the mound. Mendez served as player-manager and the “player” part of that title included part-time shortstop despite a weak bat. Rogan and Donaldson manned the outfield most days when they were not pitching, both batting near .300 and swiping several bases for good measure. George Carr, Bartolo Portuondo, and Hurley McNair exemplified the Monarchs’ potent combination of hitting for average and stealing bases once they got on base.

The rise of the Detroit Stars as a creditable challenger to the American Giants in 1919 carried over to the 1920 season. American Giants alumnus Pete Hill managed the Stars while also taking regular assignments in the outfield. Hill was joined by former Chicago teammates catcher Bruce Petway and pitcher Bill Gatewood. The addition of Lyons, with his impressive combination of slugging and speed, added to the sense of expectation. On the mound, Bill Holland worked alongside Gatewood in providing as daunting a one-two punch as any club.

Ultimately, as happened throughout the prior decade of independent play, the American Giants proved too strong for the competition. Chicago won the inaugural NNL pennant with a .717 winning percentage (43-17-2), besting nearest challengers Kansas City (44-33-2, .571, 7½ games behind) and Detroit (37-27, .578, 8 games behind) by a comfortable margin. Outfielder Cristobal Torriente and second baseman Bingo DeMoss paced an offense that possessed neither overwhelming power nor speed, but had a knack for getting on base long before the value of walks became appreciated. Backstop Jim Brown minimized any sense of loss by Petway’s departure to Detroit in 1919.

Former Star Dave Malarcher commenced a long association with the American Giants, as third baseman and later as Foster’s managerial successor. Foster’s days on the mound were over, but the pitching was in capable hands. Tom Williams, recruited from Hilldale, joined Dave Brown and Tom Johnson in anchoring the NNL’s most imposing group of pitchers. The American Giants were effectively wire-to-wire champions notwithstanding the absence of daily standings and box scores to mark the accomplishment.

While managing his club to the title, Foster also wore his league-president “hat” in continuing to promote the idea of a truly national association of Black clubs. His efforts led to the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants accepting associate membership status during the campaign. The NNL had agreed not to raid the roster of an associate member. In return for not having their players poached, the Bacharach Giants agreed to travel west to play against NNL clubs. With Cannonball Dick Redding pitching, NNL teams did not mind the attendance boost that usually accompanied a Bacharach Giants visit.

After the season, the newly minted champion American Giants traveled east to return the favor, meeting the Bacharach Giants at major-league venues Ebbets Field and Shibe Park. The clubs split six games and, in the series, Foster saw the potential for a Black World Series that would match the best of East and West.18

The December league meeting in Indianapolis provided the capstone to a successful NNL season. It was claimed that one million fans had patronized NNL games; other sources peg the figure at closer to 600,000.19 Whatever the exact figure, the league appeared to have been a financial success, with Foster proclaiming all clubs profitable; and the meeting featured constitutional changes to secure those gains. To maintain respectability with the public, the owners approved changes to fine or punish inappropriate conduct by owners and players and prohibited managers from yanking their teams off the field as acts of protest. To bind the clubs even more closely to the association, the deposit was also increased to $1,000.

With Foster continuing to think nationally, Eastern power Hilldale joined Atlantic City as an associate member, and their deposit would be the subject of a dispute when the Pennsylvania club joined the Eastern Colored League in 1923. There were changes for the NNL’s Ohio contingent, as the Dayton Marcos moved to Columbus for 1921 with Sol White managing the re-christened Buckeyes; meanwhile, the Cuban Stars secured Redland Field in Cincinnati as a home base.

The “ship” had proved seaworthy, so to speak, and the NNL was poised to continue an upward trajectory in building off the successes of the 1920 season.

JOHN BAUER resides with his wife and two children in Bedford, New Hampshire. By day, he is an attorney specializing in insurance regulatory law and corporate law. By night, he spends many spring and summer evenings cheering for the San Francisco Giants, and many fall and winter evenings reading history. He is a past and ongoing contributor to other SABR and baseball history projects.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following:

baseball-reference.com

seamheads.com (statistical references and roster information are generally to this website.)

Graf, John, ed. From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2020).

Holway, John B. Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988).

Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball Was White (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970).

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994).

Notes

1 Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing & Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932 (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1994), 79.

2 Michael E. Lomax, Black Baseball Entrepreneurs, 1902-1931: The Negro National and Eastern Colored Leagues (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2014), 39.

3 Lomax, 57.

4 Mark Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues: 1884 to 1955 (Toronto: Citadel Press, 1995), 123.

5 Lomax, 101.

6 Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2007), 36.

7 Lanctot, Fair Dealing, 72.

8 Larry Lester, Rube Foster in His Time: On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseball’s Greatest Visionary (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2012), 113.

9 Lomax, 247.

10 Lanctot, 82.

11 Lester, 116.

12 Lanctot, 82.

13 Lanctot, 83.

14 Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues, 103.

15 Lomax, 250.

16 Debono, 75.

17 Lanctot, 84.

18 Debono, 80.

19 Debono 82; Lomax, 39.