Not Chiseled in Stone: Baseball’s Enduring Records and the SABR Era

This article was written by Gary Gillette - Lyle Spatz

This article was published in Fall 2011 Baseball Research Journal

When Pete Rose hustled down to first base after rapping out base hit No. 4,192 on September 11, 1985, neither he nor the adoring crowd at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium knew that their hero had already passed Ty Cobb’s revised total of 4,189 career hits. Many baseball records are erroneously regarded as sacrosanct: these historic numbers may be burned into our brains, but they are not chiseled in stone.

Students of the game must accept the following basic, if troubling, precepts:

- Despite the hard work and admirable precision of baseball’s official scorers and official statisticians, there are an uncounted number of mistakes in baseball’s historical record.

- Despite baseball’s long obsession with its numbers, specific details about its history are not always known; in some cases, they are not even knowable.

Baseball’s “figure filberts” (as the ink-stained wretches in the press box used to refer to SABR members and their antecedents) and historians have done yeoman work in filling in missing details and correcting erroneous beliefs about the patrimony of our National Pastime.

IMMORTAL PLAYERS, NOT ETERNAL RECORDS

A look at the first players enshrined in baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1936 shows that every one of this immortal quintet has seen changes to the numbers presented as their “official statistics” since SABR was formed four decades ago.

- TY COBB: At-bats changed from 11,437 to 11,434; Hits from 4,191 to 4,189; Batting average from .367 to .366; RBIs from 1,933 to 1,938; Runs from 2,245 to 2,246; Stolen bases from 892 to 897.

- WALTER JOHNSON: Wins changed from 413 to 417; Losses from 277 to 279; Complete games from 532 to 531; Innings pitched from 5,923.2 to 5,914.1; Hits allowed from 4,925 to 4,913; Walks from 1,405 to 1,363; Strikeouts from 3,499 to 3,509.

- CHRISTY MATHEWSON: Wins changed from 367 to 373; Losses from 186 to 188; Shutouts from 77 to 79; Games from 634 to 636; Complete games from 434 to 435; Innings pitched from 4,777.1 to 4,788.2; Hits allowed from 4,216 to 4,219; Walks from 838 to 848; Strikeouts from 2,502 to 2,507.

- BABE RUTH: Games changed from 2,502 to 2,503; RBIs from 2,217 to 2,213; Walks from 2,056 to 2,062.

- HONUS WAGNER: Games changed from 2,787 to 2,794; At-bats from 10,430 to 10,439; Hits from 3,415 to 3,420; Batting average from .327 to .328; Doubles from 640 to 643; RBIs from 1,732 to 1,733; Runs from 1,736 to 1,739; Stolen bases from 722 to 723.

The records of several other immortals who reached Cooperstown in the next three elections have been changed as well.

- GROVER ALEXANDER: Wins changed from 374 to 373; Shutouts from 88 to 90; Games started from 598 to 600; Complete games from 439 to 437; Innings pitched from 5,189.1 to 5,190; walks from 953 to 951; strikeouts from 2,199 to 2,198.

- EDDIE COLLINS: Games changed from 2,825 to 2,826; Hits from 3,310 to 3,315; Doubles from 437 to 438; RBIs from 1,299 to 1,300; Runs from 1,817 to 1,821; Stolen bases from 743 to 741.

- LOU GEHRIG: Games changed from 2,163 to 2,164; Doubles from 535 to 534; Triples from 162 to 163; RBIs from 1,990 to 1,995.

- GEORGE SISLER: Games changed from 2,054 to 2,055; At-bats from 8,262 to 8,267; Hits from 2,811 to 2,812; Triples from 165 to 164; Home runs from 99 to 102; Runs from 1,283 to 1,284.

- TRIS SPEAKER: At-bats from 10,205 to 10,195; Batting average from.344 to .345; Doubles from 793 to 792; Triples from 224 to 222; Home runs from 115 to 117; RBIs from 1,527 to 1,529; Runs from 1,881 to 1,882.

- CY YOUNG: Wins changed from 509 to 511; Won-Lost percentage from .617 to .618; Games started from 816 to 815; Complete games from 750 to 749; Shutouts from 77 to 76.

Some other changes are worth noting, including two of much more recent vintage.

- ROGER MARIS & MICKEY MANTLE: In 1961, Roger Maris of the Yankees was mistakenly credited with a run batted in. The change dropped his season total from 142 to 141 and meant that Maris was no longer the American League’s sole RBI leader that year, but instead was tied with Baltimore’s Jim Gentile. Maris had also been thought to have been tied with teammate Mickey Mantle for the AL lead in runs scored that same year. But Mantle had been incorrectly awarded a run, leaving him with 131 runs after adjustment, one shy of Maris’s league-leading 132. The Mantle & Maris changes were not made by MLB until 2008 even though they had been known about for more than a decade.

- TED WILLIAMS: Two additional walks found for Ted Williams in 1941 raised his league-leading total from 145 to 147. The two 1941 walks, plus one found in 1951, raised his career total from 2,018 to 2,021.

- OLD HOSS RADBOURN: Radbourn holds the record for most wins in a season with 59 in 1884. In 1971, his win total was thought to be 60. However, because an uncredited win for Radbourn was discovered in 1889 (giving him 20 that year rather than 19), his 309 career wins remain unchanged. Radbourn’s career losses total did change from 195 to 194, though.

- HACK WILSON: Hack Wilson holds the single-season major league record for most runs batted in. Wilson was thought to have driven home 190 for the 1930 Chicago Cubs, but an additional RBI discovered in the second game of a July 28 doubleheader that year has upped that total to 191.

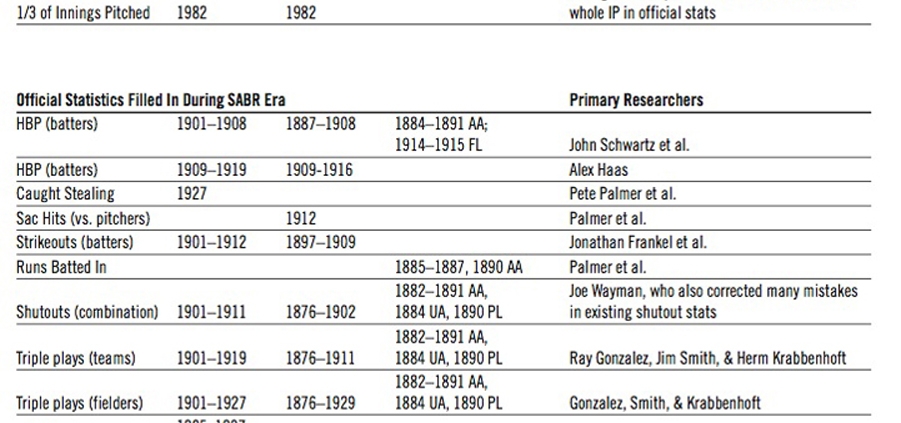

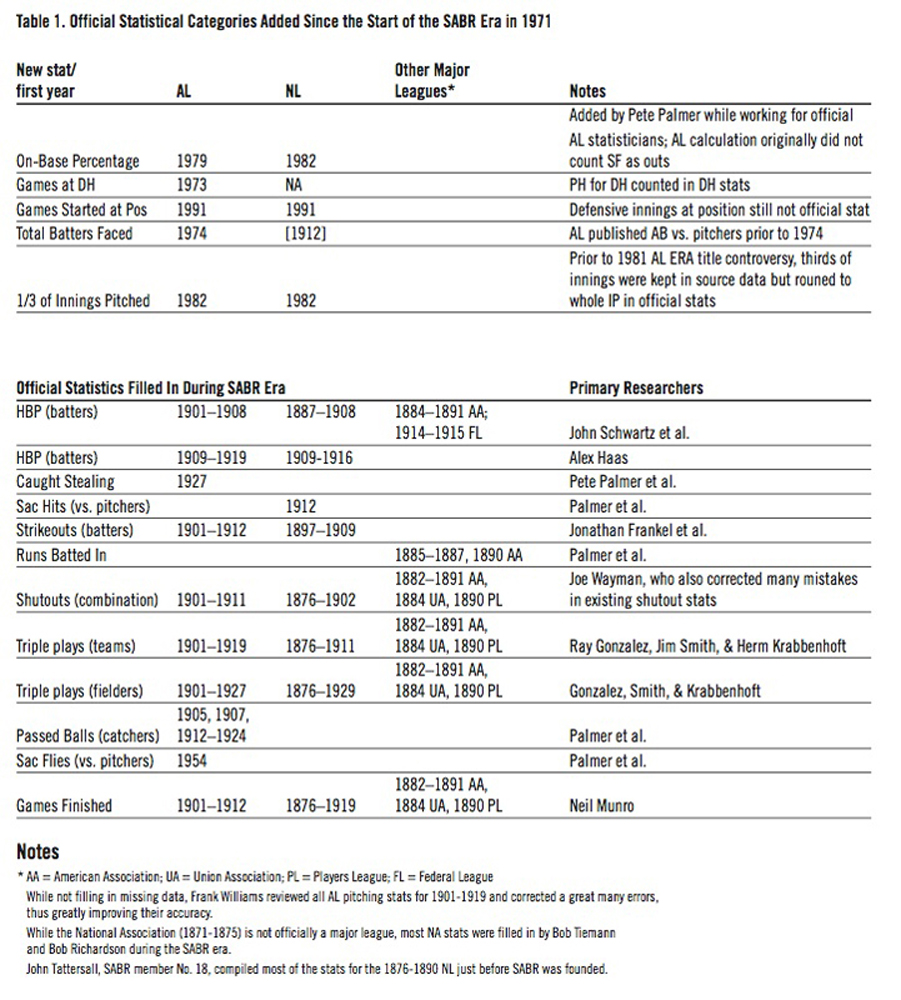

Table 1: Official Statistical Categories Added Since the Start of the SABR Era in 1971

(Click image to enlarge.)

If you think that list is impressive, there’s a lot more to come. Internet and Web access, combined with the digitization of source material and Retrosheet’s ground-breaking publication of play-by-play accounts, box scores, and game logs, has greatly accelerated the process of researching and verifying mistakes in the official records. Indefatigable SABR members like Trent McCotter and Herm Krabbenhoft are investigating many other apparent discrepancies. For the specifics of Krabbenhoft’s current campaign, which affects Lou Gehrig, Hank Greenberg, and the AL single-season RBI record, check out his amazingly scrupulous articles in this BRJ and the previous volume. (Note: Links to more of Krabbenhoft’s statistical research can be found on his SABR author page.)

While a high school student, McCotter decided to begin a game-by-game review of Ty Cobb’s career. He found mistakes in five or more games in the “Georgia Peach’s” official batting stats in important categories like at-bats, runs, walks, stolen bases, and RBIs, mostly from 1905–1917. (Some of these errors compensate for others, and other errors may well be discovered later in Cobb’s career, so the net effects are not known yet.)

McCotter believes the number of mistakes in Cobb’s RBI numbers is probably much higher, but this is much harder to verify. He also found 31 cases where Cobb’s fielding position was listed incorrectly in the official daily stats, mostly the wrong place in the outfield—they wouldn’t show up in the seasonal totals that reported only “Games in the Outfield.”

AMATEUR VS. PROFESSIONAL

McCotter and Krabbenhoft are both amateurs and SABR members—indeed, virtually all of the important work being done in this field is by amateurs. While more prolific than most, they are otherwise typical of the type of amateurs that SABR has historically helped and also produced. Professionals occasionally assist these dogged researchers, and professional baseball writers, historians, and statisticians certainly benefit from the fruit of these amateurs’ labors. Far more often, though, SABR’s corps of expert amateurs is called upon to help the pros when they’re looking to get things right.

Merriam-Webster.com gives three definitions for the word amateur: devotee, admirer; one who engages in a pursuit, study, science, or sport as a pastime rather than as a profession; one lacking in experience and competence in an art or science.

The devoted sleuths who spend their nights, weekends, holidays, and vacations pursuing these issues definitely qualify as amateurs according to sense No. 1 above. Definition No. 2 is also spot-on, as most are not getting paid to do the legwork and don’t expect their work to have any monetary value.

Definition No. 3 is sometimes unfairly used to disparage this corps of researchers, hurled to draw the focus away from the merits of their work.

PERSPICACITY PLUS PERSPIRATION

Lest anyone think that this efflorescence of records-altering historiography is a function of a new generation of statistical Maoists bent on an agate-type cultural revolution, consider the wisdom of SABR’s founders four decades ago. SABR’s Baseball Records Committee was formed by the young organization’s directors in 1975, with the mandate “to establish an accurate set of records for organized baseball.” A tall order, indeed, but one that SABR has subsequently strived mightily to fulfill.

In 1993, Lyle Spatz (then and now chair of SABR’s Baseball Records Committee) wrote:

Over the years, researchers have uncovered many errors and inconsistencies in baseball’s historical record. These errors are of two major types: (1) those errors that deal with accomplishments, positive or negative, that have been accepted as major league or individual league records: the most, the highest, the fewest, the lowest, etc., or (2) errors in the yearly and lifetime records of an individual, or a team…

For the overwhelming mass of individual, team, and league statistics, these publications are in agreement and are correct. However, baseball’s record-keeping has not always been so meticulous as it is today. This is particularly true of the game’s early years. There are numerous cases of omissions, transpositions, double-counting, addition errors, and… illegibility… that occurred at the original source (in the accounting of individual games), or in the league’s accounting at year’s end.

Other mistakes have come about as a result of the work done in the compilation of the encyclopedias and record books, some as a result of putting together the Information Concepts Corporation [sic] (ICI) data in the 1960s. ICI data were collected for those years and categories for which official sheets were not available, and together with those official sheets formed the data base for the encyclopedias. Assembling these volumes is such an enormous undertaking, that it is not surprising that errors occurred. This is in no way a criticism of those responsible for these publications; that there are so few errors is to their everlasting credit. We cannot emphasize that strongly enough. Those of us who do baseball research understand how great a debt we owe them.

The players affected by the changes that we have made range from fringe players to Hall-of-Famers. In some cases we have dealt with icons of the game, men such as Walter Johnson, Tris Speaker, and Lou Gehrig. Their accomplishments are legendary, and certain numbers associated with them are so imbedded in the memory of baseball fans that some think it sacrilegious to alter them. Those of us who attempt to do so are accused of being “fanatical crusaders,” more obsessed with statistics than with the “romance” of the game. Nothing could be further from the truth. Each person who has contributed to this study has loved the game since childhood and continues to do so. It is inconceivable that anyone who didn’t love baseball would devote as much time to studying it as we do. But as Aristotle said of his mentor, “Plato is dear to me, but dearer still is truth.” That is basically what we are, seekers of truth, not for the purpose of inflating or deflating the accomplishments of one player at the expense of another, but to ensure that each player’s accomplishments are accounted for as accurately as possible.

Thus, the purpose… is not one of revolution, but rather of evolution. We want to make the historic record a little more accurate, and a little more consistent.

The people responsible for the research… have pored over old newspapers, guides, official records, and ICI records. They have looked at miles of microfilm, from a variety of sources, searching through box scores and comparing game accounts. In all cases, they adhered to the scoring rules and customs of the day. As previously stated, only in very few cases did they find what seemed to be a demonstrable error…

We fail to see how clinging to a number that is obviously wrong adds to the “romance” of the game, or how accepting a correct one detracts from it…. Therefore we offer these corrections and reconciliations in a spirit of collegiality and cooperation. We trust that they will be received in the same way…

THE LEGACY OF SABR

SABR was founded two years after the momentous debut of the Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia, made possible by the Herculean efforts of David Neft and Information Concepts Incorporated (ICI). Neft would become SABR member No. 74 in November 1971.

The table at right details just how much baseball’s statistical landscape has changed since that watershed year. Everyone named in it is a stalwart SABR member, and SABR provided an invaluable framework for their pioneering work. While you might scoff at the value of knowing how many sacrifice bunts individual pitchers allowed in 1912, your understanding of the careers of all-time greats like Cy Young, Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, and Pete Alexander is framed by SABR members’ contributions.

Moreover, it is not an overstatement to say that the addition by Pete Palmer (SABR member No. 27) of On-Base Percentage to the roster of official batting statistics would eventually alter the way the modern game is played.

The appointment of baseball historian, SABR confrere, and former Total Baseball encyclopedia co-editor John Thorn as the second official historian for Major League Baseball in March 2011 will also likely affect the landscape in the future. MLB created its official historian position in 1999 and appointed veteran Chicago sportswriter and SABR member Jerome Holtzman to fill it.

Holtzman had revamped the Grand Old Game’s canon of pitching statistics in 1969 when he persuaded baseball to officially adopt his Save statistic—which would ultimately completely rearrange pitcher usage and the composition of pitching staffs. Other than a paradoxical decision to reverse longstanding practice by counting walks as outs in 1876 and walks as hits in 1887, Holtzman’s reign until his death in 2008 did not affect the status quo ante.

OBP—along with Palmer’s later analytical development of OPS (On-Base Plus Slugging)—fundamentally rewired the way we perceive baseball offense. The analytical innovations of seminal writer and analyst Bill James (SABR member No. 407, who became famous in the early 1980s for his revolutionary and bestselling Baseball Abstract), combined with the masterworks of Messrs. Palmer and Thorn (The Hidden Game of Baseball and Total Baseball) later that decade, popularized sabermetrics—a neologism coined by James—and laid the foundation for what would become known as “Moneyball”.

During the four decades of the SABR era, the Society and many of its members—titans in the fields of baseball history, research, and analysis—have truly rewritten baseball’s legendary “book.”

GARY GILLETTE is co-chair of the SABR Ballparks Committee and a member of the SABR Board of Directors. He has written or edited numerous baseball books, including “Big League Ballparks” and the “ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia”. Along with Stuart Shea, he is currently blogging the fabulous 1961 season at 61at50.com.

LYLE SPATZ has been a member of the Society for American Baseball Research since 1973 and chairman of the Baseball Records Committee since 1991.