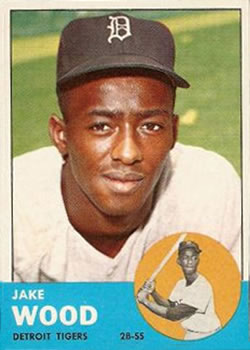

Jake Wood

Jacob “Jake” Wood Jr., an African American from Elizabeth, New Jersey, starred at shortstop for the baseball team at Thomas Jefferson High, played one season at Delaware State University, and signed with the Detroit Tigers in 1957.

Jacob “Jake” Wood Jr., an African American from Elizabeth, New Jersey, starred at shortstop for the baseball team at Thomas Jefferson High, played one season at Delaware State University, and signed with the Detroit Tigers in 1957.

Jake was a natural, one of two outstanding athletes in the family. Youngest brother Richard enjoyed a 10-year career in the National Football League, playing linebacker from 1975 through 1984, the last nine years for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

On April 11, 1961, Jake, the slender, speedy, hard-hitting second baseman for Detroit, debuted on Opening Day at Tiger Stadium against the Cleveland Indians. Hitting leadoff, the right-handed batter went 1-for-4, belting a two-run home run in the seventh inning off right-hander Jim Perry, but Perry and the Indians went on to win, 9-5.

Wood played his entire major league career, from 1961 to 1967, in a turbulent decade when black players being accepted by teammates and fans was less difficult than during earlier years. No less than 116 black players had debuted in the majors before 1960, so baseball’s door was open.

The 1961 season was memorable for the Tigers and for Wood in many ways. Detroit, led by big hitters like Norm Cash, Rocky Colavito and Al Kaline and by stellar pitchers like Frank Lary, Jim Bunning, Don Mossi and reliever Terry Fox, contended with New York for the American League pennant for most of the summer. On September 1, 2 and 3, the Bronx Bombers won three straight home games over Detroit. In the end, the Tigers finished in second place, 8.5 games behind the Yankees, Roger Maris hit a then-record 61 home runs, Cash led the league in hitting with a .361 average, and Wood averaged .258 with 17 doubles, a league-best 14 triples, 11 home runs and 69 RBIs. Stealing a career-best 30 bases, he led off Detroit’s potent order, a lineup that led the Bengals to a 101-61 record in the league’s first 162-game season. Wood, showing talent, poise, and class, played all 162 games.

Wood wasn’t the first black player to crack Detroit’s lineup, but he was the first to play his way through the Tigers’ minor league system and make it with the major league club as a regular. Ozzie Virgil, born and raised in the Dominican Republica, was traded from the San Francisco Giants to the Tigers along with Gail Harris on January 28, 1958. Virgil played his first game in Tiger uniform against the Washington Senators in an 11-2 victory at Griffith Stadium on June 6, 1958, making him the player who broke Detroit’s “color line.” Larry Doby, the first African American to play in the American League on July 5, 1947, came to Detroit in a trade with Cleveland on March 21, 1959. Doby, a two-time American League home run king and later a Baseball Hall of Famer (1998), played as a Tiger for the first time in a 9-7 loss to the White Sox at Briggs Stadium (renamed Tiger Stadium in 1961) on April 10, 1959. Late in the season, right-hander Jim Proctor, another promising black athlete, pitched in two games, the first a 5-0 loss to the Senators on September 14, 1959. Proctor, who worked his way through the Tigers’ system before Wood, pitched in two games, finishing his only major league season with an 0-1 mark.

Born to Roberta and Jacob Wood Sr. on June 22, 1937, in Elizabeth, a few miles south of Newark, Jake was the second oldest child and the oldest son of nine children. Jake’s father was a handyman who worked at different jobs, and his mother was a housewife. The neighborhood where the family lived was integrated. With no television to watch and little space in the house, the children went outside and made up games. Stickball was a favorite, partly because nobody had any equipment for baseball. Someone usually came up with an old, taped ball, someone else found a broomstick, the bases could be boards or places in the street, the kids made up their own rules for what was a hit or an out, and Jake and his friends played ball together for hours.

Asked about his early years, Wood, speaking in 2013, remembered, “I went to an integrated grammar school and an integrated high school in Elizabeth. We had all types of people, and we lived in a diverse neighborhood. I didn’t grow up divided by race or religion, or things of that nature, because it wasn’t taught in our household. One of the things my father advocated for us growing up was to be careful how you treat people. He didn’t discriminate against anybody.”

Wood thrived on sports. He played intramural football and basketball at Lafayette Junior High, but at age fourteen and fifteen, he played baseball in the local Police Athletic League. He and several buddies played for Jimmy’s Automotive, and they received a cap and a T-shirt, typical for sandlot teams in the 1950s. Once at Jefferson High, Jake concentrated on baseball, and with his talent, quickness and speed, he became a star shortstop for Abner West, the coach. Jake played American Legion baseball for the Argonne Post with Edward “Buzzy” Fox as the coach. Wood recalled that Jefferson High won the state championship in 1955, his senior year.

Wood went to college, but he loved baseball. “I went to Delaware State College and played baseball for Coach Bennie George,” Jake said. “Matter of fact, Irving ‘Rabbit’ Jacobson was the recreation director in Elizabeth and the area scout for the Detroit Tigers. On our high school squad when we won the championship, he signed three other guys to contracts for professional baseball, but he always kind of adopted me. Jacobson said he would sign me to a professional contract, but he wanted me to go to college first. Your first priority, he said, was to get an education. He said, ‘Any time you want to sign, I’ll sign you.’ I graduated in 1955, and he signed three other guys: Richard Jones, a pitcher, Jackson Queen, and William Bennett.

“I went to Delaware State College in the fall of 1955, and I stayed there through 1956. I played baseball for Delaware State, but I always wanted to play professional baseball. I told Jacobson I wanted to sign in the winter of 1956, so 1957 was my first year in the Tigers’ organization. I didn’t go back to Delaware State after the spring break of 1957.”

In February 1957, Wood went to Lakeland to Tigertown, Detroit’s rookie camp that was held in advance of the team’s regular spring training for the second year. Unknown to Jake, Lakeland and Florida were segregated in the 1950s as well as the 1960s, making life off the diamond tougher for black players. Wood later called Lakeland a “culture shock.”

During their baseball years, most of Detroit’s players preferred not to talk about the segregation they all saw in Lakeland. “Private homes in spring training instead of motels,” observed Tiger Hall of Famer Al Kaline in 2010. “Different water fountains, and that’s just the tip of it. These men, and many others, went through some awful things.”

“Tigertown was part of an old Air Force base,” Wood recollected in 2013, “and they had barracks. We all lived together in the barracks, but we were separated in terms of sleeping facilities. The room we had was all black guys, and they had another, larger room for the white guys. There might have been about a dozen black guys. They all lived together, from the rookies up through the guys who had been playing for a couple of years.”

The Tigers liked Wood in 1957, and he was assigned to play at Erie, Pennsylvania, of the Class D New York-Penn League. Erie had one other black player, Jim Branch, a 19-year-old outfielder from Detroit, but he was released after hitting .263 in 14 games. Ted Brzenk, a rookie third baseman from Milwaukee and a star athlete who played football, basketball, and baseball at Northwestern University as a freshman, signed with Detroit in 1956. Speaking in 2013, Brzenk called the facilities at Tigertown an “eye-opener” for him, because, like most players from outside the South, he had not personally witnessed segregation.

Brzenk, who became lifelong friends with Wood, remembered the separate facilities in Lakeland as well as the bus trip north to Pennsylvania taken by Erie’s players. “Black players had their own water fountains, rest rooms, and things like that,” Brzenk said. “When we left Tigertown to drive to Erie, we rode a bus. When we traveled south of the Mason-Dixon Line, black players couldn’t go into the restaurants with us. I remember that we had to carry food to Jake on the bus. I don’t know which rest rooms he used. I know when we stayed overnight, Jake didn’t stay with us. Once we reached Pennsylvania, he stayed with us. I was Jake’s roommate in Erie, but that was north of the Mason-Dixon Line.”

On the field, Wood, who was quiet and modest, performed well for Erie, and Brzenk, who batted .281 with 11 homers, made the league’s all-star team. Ted, who spent five seasons on the minors but never made it to the majors, said, “Without a doubt, Jake Wood was the best player I played with in the minor leagues.”

Exceptionally fast, Jake, who had quick hands and a quick bat, hit .318 with 15 homers and 52 RBIs in 102 games, mostly at shortstop, but he committed 43 errors and fielded .882. The Erie Sailors, who acquired infielder Dick McAuliffe after he graduated from high school, finished second with a 70-47 record, four games behind first-place Wellsville (N.Y.). Erie won the New York-Penn Shaughnessy Playoff Championship, beating third-place Corning (N.Y) in the semifinal round, and stopping fourth-place Batavia in the playoff finals.

In 1958 the Tigers again sent Wood to the advance camp at Tigertown, and he moved on to Durham in the Class B Carolina League. Jake remained in Durham only a few weeks before Detroit sent him to the Idaho Falls of the Class C Pioneer League. Also, Ted Brzenk married his sweetheart, Barbara. Brzenk trained with Augusta, Georgia, of the Class A South Atlantic (Sally) League, but he and Wood were reunited in Durham for the first two weeks of the season. Jake remembered that after Ted and Barbara were married in April, they arrived in Durham and “she came out and came running up to me, and hugging on me. I said, ‘What are you trying to do down here, get me killed?’ We laugh about it until this day!”

Wood hit .283 for Durham in 14 games, but he was sent to Idaho Falls, where he played 103 games and batted .308 with nine home runs and 70 RBIs. Durham was using Jake in the outfield, but Idaho Falls played him at shortstop, where he committed 43 errors for the second year in a row. Handling more chances, he improved his fielding to .909. Wood also found life easier off the diamond. He did remember being refused service once at a bar where he and his teammates went for a beer in Missoula, Montana. Jake got along fine with other players, but he saw only one other African American in the entire town of Idaho Falls.

During spring training in 1959, Larry Doby, Jim Proctor, Wood and others demanded black players be given a rental car for away games. The Tigers agreed. After Tigertown, Wood split the season between Knoxville of the Sally League and Fox Cities, located in Appleton, Wisconsin, in the Class B Three-I League. Having accepted the segregated living facilities in Lakeland, Wood, who was conscientious, motivated, and determined, started the season with Knoxville, where he hit .300 with five home runs and 29 RBIs in 58 games, mainly at shortstop. In the season’s second half, he moved to Fox Cities in the Washington Senators’ system. Jake never understood why the Tigers loaned him, but being a positive thinker, he made the best of the experience. Fox Cities, however, had an excellent shortstop, Zoilo Versalles, so Wood played mainly second base. In 159 games he hit .317 with three homers and 27 RBIs.

After spring training in 1960, the Tigers sent Wood, whose record made him a major league prospect, to Triple-A Denver of the American Association, and he enjoyed his fourth .300 season. Playing for Charlie Metro, Wood handled second base. Fielding .958, he topped the league in errors with 34, but he also led in assists with 436 in 149 games. Hitting well, Jake paced the circuit in triples with 18, and he averaged .305 with 24 doubles, 12 homers, and 76 RBIs, making his power numbers and run production among his best ever.

Denver led the league with an 88-66 record, and several Bears made the All-Star team: first baseman Larry “Bobo” Osborne, who hit .342; second baseman Steve Boros, who led the loop in runs scored with 128 and was the league’s MVP; Jim McDaniel, an outfielder who hit .288; catcher Mike Roarke, who batted .255; and right-hander Phil Regan, who had a 9-3 record with a 3.06 ERA. Denver’s roster was loaded with players who had played for the Tigers, or soon would play for Detroit, including Wood, Osborne, Boros, Roarke, Ossie Alvarez, Fred Gladding, and Bubba Morton, a black outfielder who debuted with Detroit in 1961, eight days after Wood first played.

Wood attributed his solid season at Denver to Charlie Metro, a former major leaguer who played with Detroit and the St. Louis Browns in the 1940s and who managed, coached, and scouted in the majors in the 1960s. Metro told Wood that he would be Denver’s second baseman, despite the fact that Wood was hitting less than .200 at the time. “I don’t know who he had to convince or cajole,” Wood observed, but “I was the second baseman at Denver, and I had a good year. At the end of the year, Charlie Metro came up to me, and he said, ‘I want to thank you.’

“I said, ‘For what? I should be thanking you.’ I do not know what type of grief he had to put up with to keep me at Denver, but he was a man of his word. He said I was going to be the second baseman, and I was the second baseman. Sometimes in life people do tell you things, but if enough pressure is put on them, it goes in one ear and out the other. He made a commitment to me, and he kept it. So I thank God for Charlie Metro and his commitment.”

Equally important, Wood received an opportunity, because second base was open. On December 7, 1960, with Jake waiting in the wings, Detroit traded stellar second baseman Frank Bolling, along with a player to be named later (Neil Chrisley), to the Milwaukee Braves for fleet Billy Bruton, considered one of the best center fielders in baseball; catcher Dick Brown, who, with Roarke, became part of Detroit’s backstop tandem in 1961; infielder Chuck Cottier, soon traded to the expansion Washington Senators; and right-hander Terry Fox, a second-year pitcher who became the Tigers’ main man out of the bullpen despite arm problems, fashioning a 5-2 mark with a stingy 1.41 ERA and 12 saves in 1961.

Lakeland remained segregated in the early 1960s, but Wood lived with his in-laws, who had an apartment there. Jake married Janice Sullivan after the 1958 season, and the couple later had a daughter, Adriann, and a son, Ronald. About Lakeland that spring, Jake recalled, “Billy Bruton, I think, stayed in a local family’s residence. The hotel that the Tigers used was still segregated.” According to The Sporting News, the Tigers moved their players from the segregated New Florida Hotel to an expanded Holiday Inn in Lakeland for spring training in 1963, the year of the “I Have a Dream” speech by King and the assassination of President John Kennedy.

Life in the Motor City, however, worked for Wood. “The climate in Detroit in the African American community was different,” he explained. “In the apartment where we used to live, I came into contact with ordinary people, and we formed lifelong bonds. I was just ‘Jake’ to them.” Over his seven seasons with the Tigers (he was traded in 1967), Wood lived in several places: “One year I rented a house owned by Lenny Green, who was from Detroit and at that time he played for the Minnesota Twins. In the seven years, I probably lived in five different locations. It was a great time, a fun time.”

On the diamond, in the dugout, and in the clubhouse — where the players usually develop a camaraderie that makes baseball a memorable part of each player’s life — Wood and the Tigers enjoyed an exceptional season. Detroit staged a long-overdue pennant race with New York, and until they lost three tense games on September 1-3 at Yankee Stadium, many observers and fans figured the Bengals would be in the World Series for the first time since 1945. On August 31, 1961, the Tigers were 1.5 games behind the Yankees, but New York won three straight by scores of 1-0, 7-2 and 8-5. Deflated, the Tigers lost three more to Baltimore and twice to Boston before defeating the Red Sox, 3-1, on September 9. After that victory, Detroit trailed New York by ten games, and the pennant race was over. In the end, the Detroit won second place money. Wood said each Tiger’s share of the World Series receipts was around $1,200.

Wood, who scored 96 runs, was the Tigers’ best base runner, stealing 30 bases, and he became a favorite of many fans. He ranked third in the league for stolen bases behind “Little Luis” Aparicio of the White Sox with 53 and Dick Howser of Kansas City with 37. Detroit’s Billy Bruton, then 35 (Bruton was actually 39, but he was advised to take four years off his age when signing with the Braves in 1949), still had the speed to steal 22 bases. Bruton also scored 99 runs, fourth for the Tigers behind Rocky Colavito (129), Norm Cash (119) and Al Kaline (116).

However, Wood’s problem in the eyes of Detroit’s management was that he set a new league record with 141 strikeouts, compared to drawing 58 bases on balls. While he made Topps’ “All-Star Rookie Team,” Wood was sent to Tampa, Florida, to learn bunting from the Tigers’ new third-base coach, George Myatt. According to manager Bob Scheffing, Wood beat out only four bunts during the 1961 season, and Jake sacrificed just twice. He spent two weeks with Myatt laying down up to 300 bunts a day at Al Lopez Field in Tampa. “This boy could be the best of our young players,” Scheffing observed, but Jake needed better bunting skills to help his on-base percentage (.320 in 1961).

In 1962, however, Wood slumped to .226 with an on-base percentage of .291, the Tigers finished in fourth place with an 86-76 record, and, by August, youthful Dick McAuliffe had taken over at second base. Before that, Scheffing, a player’s manager, had given Jake every opportunity. Wood did improve his fielding (he made only six of 25 errors after July 23 in 1961). Before spring training, Scheffing told Watson Spoelstra, the Tigers’ beat writer for the Detroit News, that Wood needed to “cheat” on double-play situations (move closer to second), get his throws away quicker, and bunt better. “Now if he could put two out of three bunts in fair territory,” Scheffing said, “it would make him a dangerous hitter.”

Jake also went from a 33-ounce bat to a 35-ounce model, and he choked up two inches to get more wood on the ball. By June 1, Wood was not playing every day. Scheffing was also using McAuliffe, a hard-hitting left-handed batting infielder. Wood hit in splurges, including a long homer to center field against the Red Sox on May 31, but he had too many 0-for-4 days. By June 25 he had stolen 18 bases, but he and McAuliffe were being platooned (McAuliffe faced right-handers, Wood saw mostly left-handers). When McAuliffe sat out of a game on September 2, Wood made his first start in four weeks, singling in four trips.

When the season ended, Wood was hitting below .230. In 404 plate appearances (compared to 731 in 1961), he hit 10 doubles, five triples, and eight home runs, and he contributed 30 RBIs (down from 69 in 1961). But McAuliffe had hit .263 with 12 homers and 63 RBIs. Scheffing, trying to figure how to use both McAuliffe and Wood, talked about playing Jake in the outfield in 1963, because he had too much talent to ride the bench.

The Tigers toured the Orient in October after the 1962 season ended, and, with Bruton injured, Wood played some in center field, while McAuliffe handled second base. Following an offseason of working near home in Elizabeth, Jake was one of 42 players invited to Detroit’s advance camp at Tigertown. When the 1963 season began, he was using a “short-fingered” glove with a smaller pocket so that he could get the ball away quicker on throws. “Everybody’s laughing at it,” the laconic New Jersey native remarked, “but I like the glove.”

Scheffing was impressed with Wood’s improvement at the plate in 1963. McAuliffe started the season at second, but Wood hit well when he was given a chance. By the middle of May, Wood and McAuliffe, who was shifted to shortstop, were being called the team’s “Blue-Chips Bet” to be the Tigers’ double-play combo. Wrote Watson Spoelstra, “McAuliffe, 23, and Wood, 25, are the best pair of young infielders to come up through the farm system in recent years.”

After May 5, Wood played second, McAuliffe played short, and Chico Fernandez, who was Detroit’s shortstop for three seasons, mostly rode the bench. Two months later, after the Tigers defeated the Red Sox, 6-3, on June 10, Wood was hitting .291, and McAuliffe was batting .269. “Jake is playing even better than he did in his rookie season of 1961,” wrote Spoelstra. “I’m sure Jake wasn’t feeling good in 1962,” said Scheffing. “He didn’t have the drive he has now.”

Scheffing, however, was replaced by veteran pilot Chuck Dressen on June 18, and the Tigers fashioned a 55-47 ledger for the rest of the season. Dressen particularly liked three young players, Wood, McAuliffe, and catcher Bill Freehan. Jake continued to hit hard and play well, and he had stolen 17 bases by the All-Star break.

But the kind of break that affects all ballplayers hit Wood in a game against Washington on July 25. He swung hard, as usual, and the middle finger of his left hand was dislocated. McAuliffe, on deck, pulled the finger back into alignment, but on the next swing it popped out again. Wood pinch-ran once, six days later, but he had season-ending surgery to repair the tendon of the finger on his glove hand.

Talking about the injury in 2013, Wood recalled being sent after the season to a rehab facility in West Orange, New Jersey. The big leaguer was “dejected” about not being able to play baseball due to his injury, but when he saw men and women without arms or legs in rehab, they uplifted him. “They were a blessing to me,” Jake recounted, and he became even more determined to recover.

Actually, Wood’s 1963 season was going well before July 25. He finished by hitting .271 with 11 homers, 27 RBIs, an on-base percentage of .330, and 18 steals. When he was injured, only Al Kaline, batting .321, had a higher average for Detroit. Thinking ahead about needed changes for 1964, Chuck Dressen talked about moving Wood to the outfield. “Jake is a good hitter and might get better,” Dressen commented. “He has speed and a good arm. The outfield is the place for him.”

Wood, who began his major league career with a $7,500 salary, just above the majors’ minimum in 1961, returned home to Elizabeth after each season. There he worked at a variety of jobs to support his family, including selling automobiles and working in an auto parts factory. In Detroit, he found life to his liking, and he doesn’t remember second-class treatment from fans.

“I used to laugh,” Jake recollected, “because when you take the uniform off, nobody knows you. I remember one time being in a barbershop with Billy Bruton, and the barber knew us. The barber started a conversation, ‘What do you think about the Tigers?’ We were probably on a losing streak, and one guy started going through all the negative things about the Tigers.

“The barber said, ‘What do you think about Billy Bruton and Jake Wood?’ The guy said this and that, and the barber says, ‘I want you to meet two friends of mine. This is Jake Wood and Billy Bruton.’ The guy was really surprised, and he changed his tune.”

Wood laughed about the memory, and he had no complaints about the Tigers or about Detroit. Asked if he stayed in the same hotels with other players, because, for example, Larry Doby remembered staying in black-owned hotels for most of the 1950s, Jake said the Tigers during his years had all players living in the same hotels during the regular season.

Wood did lead the AL in strikeouts in 1961 with 141, but he shrunk his whiffs to 59 in 1962 and 61 in 1963. Jake explained, “I probably reduced my swing, and there were certain pitches I liked, like the high fastball, about shoulder-high, and I probably missed it more than I hit it.” He laughed about missing the high, hard ones, adding, “I knew the strike zone a little better, and I focused putting the ball in play. Sometimes you form habits and swing a certain way, and baseball is a matter of adjustment. I just did not adjust a lot to what they were pitching to me in 1961. I adjusted better later, to a point, but not enough to keep playing.”

The Tigers’ front office, looking for a stronger lineup in 1964 after finishing fourth in 1962 and fifth in 1963, made a five-player trade with Kansas City that sent Rocky Colavito to the A’s and brought veteran second baseman Jerry Lumpe to Detroit. Afterward, Wood’s chances to play as a regular were gone, unless Lumpe was injured. Jake’s games fell to 64 and his plate appearances to 130 in 1964, when he averaged .232, hitting a single homer and driving in seven runs. In 1965, Wood made 115 plate appearances in 58 games, hitting a career-high .288 with two home runs and, again, seven RBIs.

Wood observed, “When a baseball player loses a regular position, it almost always causes self-doubts. You start to have doubts about your ability. That’s why it’s important for a young player to get to play. You have to play, because the game’s not that easy. To me, if you don’t bat a certain number of times, you lose sight of what hitting is all about. Some guys are good at sitting on the bench and getting up there and pinch-hitting, maybe one time a game. That’s not me. If you don’t play regular, you lose some of that edge. I think that’s what happened to me.

“It doesn’t help your average, your confidence, everything. You’re not yourself. You start trying to do too much. Sometimes you’re just apprehensive if you don’t play. A 90-mile-an-hour fastball turns into a 150-mile-an-hour fastball, because everything is off, your timing, your swing, your fielding. Everything is just off. There are guys, God bless ’em, that play once or twice or twice a week and still function well. Some guys can’t do it. I can’t do it. I didn’t do it.”

Wood made a bit of a comeback in 1966, playing in 98 games, making 264 plate appearances, and hitting .252 with two circuit clouts and 27 RBIs. The Tigers also had other young players competing for positions, notably African American Gates Brown, who started in left field in 1964 and hit .272 with 15 homers and 52 RBIs. Wood roomed on the road with Brown for one season, and the two became friends. Willie Horton, a black star from Detroit who soon became friends with Wood, played left field in 1965, batting .273 with 29 homers and 104 RBIs. McAuliffe played shortstop and Lumpe, a steady fielder, held down second base. Detroit finished fourth in 1964, fourth in 1965, and third in 1966, Wood’s final full season as a Tiger.

In 1967, Wood, now 30, was used in only 14 games (Jake was 1-for-20) before being sent to Triple-A Toledo, the Tigers’ affiliate in the American Association. On June 23 the Cincinnati Reds purchased him from Detroit. Between Toledo and Cincinnati’s Buffalo Bisons, also of the American Association, Jake batted .253, but he hit just one home run and drove in 13 runs. After the season, on October 11, 1967, the Cleveland Indians purchased him from the Reds, but his major league days were over.

Wood played two seasons in the high minors, hitting .248 for Portland of the Pacific Coast League in 1968 and .256 for Montgomery of the Southern Association in 1969. “In 1968 I played in Portland, which was with the Cleveland organization,” Wood recollected. “In spring training, I tore a tendon in my left wrist when me and the center fielder ran together on a fly ball, so I spent part of that year on the disabled list. In 1969 the Tigers called me sometime during the year to play at Montgomery of the Southern League. Matter of fact, your current Tiger manager, Jim Leyland, and Gene Lamont were my teammates at Montgomery. After that, I didn’t get a contract, so that was it.”

Wood, who persevered through many difficulties but remains proud of his achievements in baseball, went to work for Abraham and Straus, a department store in Brooklyn. He said, “Eventually Abraham and Straus became part of Federated Department Stores, which was Macy’s. I worked for them for 32 years. I was in the operations end of that. I was the receiving manager for merchandise. I had to supervise the loading and unloading of trucks, deal with vendors and suppliers, handle merchandise, personnel, wages, things of that nature.”

Wood, whose first wife passed away, lives with his wife Marsha in Pensacola, Florida, and he has no regrets about his baseball career. Indeed, he was still playing softball in a senior league in 2018. “I would not trade my life and my beginning and my experiences for anything in this world,” Jake said. “The places that I’ve been to through playing baseball in this country, and the people I’ve met throughout my life playing baseball, and even now, the people I’ve met playing softball, I wouldn’t trade for anything. I am truly, truly blessed.”

In March 2010 the Tigers brought Wood to Lakeland along with his teammate and friend Willie Horton to commemorate them as baseball pioneers. Horton recalled being inspired by Wood wearing the Tigers’ uniform in 1961. “Instead of spanking my butt to go to school, my dad let me go out to see him play, the first black player to come up through the [Tigers’] system,” Willie told Tom Gage of the Detroit News. Actually, Wood was the first black regular that Detroit’s system developed, and he inspired countless numbers of young guys, especially black kids.

Wood enjoys talking about baseball, enjoys playing softball, enjoys his church community, and enjoys mentoring young people. Reflecting in 2010 about his rookie season in Detroit, Jake concluded, “It was a thrill just to be out there and to be doing something that as a child I wanted to do — playing baseball. That’s why I thank God for guys like Jackie Robinson who in 1947 integrated baseball. I’m grateful for the people before me, but also for people like Willie [Horton], because he’s still paving a way for people after him.”

Last revised: December 14, 2018

Sources

Harrigan, Patrick. The Detroit Tigers: Club and Community, 1945-1995 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997). Has excellent information about the Tigers, Detroit and the community.

Heiman, Lee, Dave Weiner, and Bill Gutman. When the Cheering Stops: Ex-Major Leaguers Talk About Their Game and Their Lives (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1990). Has the recollections of several players, including Billy Bruton, indicating he was born in 1925, not 1929, as was listed in his playing career in publications like the Baseball Register (see 1962 ed.).

Moffi, Larry, and Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959 (Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 2006 edition). Has short bios on all 116 nonwhite players, starting with Jackie Robinson, who debuted in the majors through the 1959 season.

Moore, Joseph Thomas. Larry Doby: The Struggles of the American League’s First Black Player (Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications, Inc., 1988, 2011). Covers Doby’s difficulties and achievements in the American League during and after his playing career.

Gage, Tom. “Tiger Trail Blazers Still Are Standing Tall Today.,” Detroit News, March 2, 2010.

Beck, Jason. “Wood’s Path to the Big Leagues a First for the Tigers,” February 9, 2011, accessible at: http://detroit.tigers.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20110209&content_id=16605446&vkey=news_det&c_id=det.

Holzwarth, Dean. “Former Tiger Infielder Still Playing Ball at 74.” Grand Rapids Press, July 28, 2011.

Spoelstra, Watson. “Bengals Eye Gate Plunge; Step Up to Swap Counter.” The Sporting News, November 2, 1963. 17.

Spoelstra, Watson. “Negroes ‘Happy’ Over New Tiger Spring Quarters.” The Sporting News, May 9, 1962. 17.

Spoelstra, Watson. “Wood-Bruton Sock Duo Mixing Potent 1-2 Potion at Plate.” The Sporting News, June 16, 1962. 15.

Spoelstra, Watson. “Wood Earns His Diploma in Myatt School of Bunting.” The Sporting News, December 6, 1961. 29.

Spoelstra, Watson. “Young Tigers Have ‘Chance of Lifetime’ to Nab Regular Jobs.” The Sporting News, February 8, 1961. 16.

The Sporting News, for articles in the early 1960s.

Sargent, Jim. Interview with Ted Brzenk, June 11, 2013.

Sargent, Jim. Interview with Terry Fox, July 11, 2013.

Sargent, Jim. Interview with Jim Proctor, August 29, 2013.

Sargent, Jim. Interviews with Jake Wood, May 5, 2013; July 11, 2013; May 12, 2015; and June 21, 2017. Wood also wrote the Foreword for the author’s book, The Tigers and Yankees in ’61 (McFarland, 2016).

Full Name

Jacob Wood

Born

June 22, 1937 at Elizabeth, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.