Wally Moon

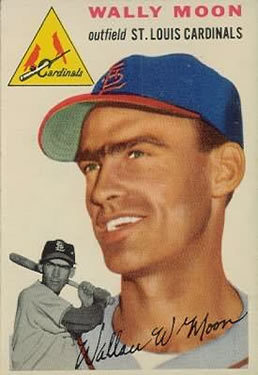

When Wally Moon came to bat for the first time in the majors, some of the home fans in St. Louis booed. Others yelled, “We want Eno.”

When Wally Moon came to bat for the first time in the majors, some of the home fans in St. Louis booed. Others yelled, “We want Eno.”

Two days earlier Enos Slaughter, a Cardinal favorite for 16 years—the hustling, hard-nosed, red-necked Country Slaughter, who left the dugout running and kept running until he hit the top step on his way back—had been cast off as surplus at age 38, traded to the New York Yankees for three nobodies. A local paper reported the trade on its front page, with a photo of the old hero weeping. Now this unibrowed, sinewy college boy presumed to take his place.

“We want Eno.”1

Facing the jeers, Moon launched a home run onto the right-field roof in his first at-bat. He hit another homer in his final at-bat of that 1954 season. Between those bookends he batted .304/.371/.435. Sportswriters voted him National League Rookie of the Year over Ernie Banks and Henry Aaron.

In a dozen years in the majors, Moon played for three World Series champions, made two All-Star teams, and won a Gold Glove. Two traits distinguished him from most ballplayers: his education—a master’s degree from Texas A&M—and his faith. He was a devoted Christian, a leader in the Methodist Church. “When it came to liquor, language, and ladies, I was out of synch with many of my teammates,” he wrote.2

Wallace Wade Moon was born in Bay, Arkansas, a swampy hamlet alongside the railroad tracks, on April 3, 1930, the middle of three children of Henry Albert Moon, a factory worker who became mayor of Bay, and the former Margie Leona Vernon. Bert Moon, who read every sports page he could get his hands on, named his second son after a famous football coach whose Alabama team had just won its third Rose Bowl. From early childhood, the boy was called “Booger” because he was afraid of the “booger man.”

Booger and his older brother, David Wayne, grew up grew up using an empty Pet Milk can for a baseball, swinging a bat made by their father. They helped pick cotton on the family farm and hired themselves out to neighbors for other chores at a quarter a day. They charged 50 cents to clean outhouses.

Bay High School didn’t have enough boys to field a baseball team. Booger played guard in basketball and excelled in American Legion baseball. Pittsburgh Pirates scout Ziggy Sears offered him a $1,000 bonus, but Booger’s father, who had left school after seventh grade, preached the value of education. Sears helped to arrange a scholarship to Texas A&M, half for basketball and half for baseball. Booger was not only the first of his family to go to college, but the first from his high school.

From Bay, Arkansas, population 400, to A&M, with its 8,000 students, was a much longer trip than the 600-mile train ride. Growing up in a house without indoor plumbing, Moon had never seen a shower. And despite the pedigree of his given names, he had never seen a football game—a bigger disadvantage for the freshman Aggie.

As an all-Southwest Conference outfielder, Moon attracted the attention of big-league scouts. After his junior year, Detroit offered him $18,000, but his dad didn’t want him to be stuck on the big-league bench as a bonus baby. Bert Moon studied the rosters of the interested teams and determined that the Cardinals farm system had few left-handed-batting outfielders like his son. He steered Wally to St. Louis for a $6,000 bonus. That was fine with Wally, who had grown up listening to Cardinals games on radio with his grandfather. The club agreed to let him play ball part time while he completed his college degree.

When the 1949-50 school year ended, Moon began his professional career with a brief stop at Double-A Houston before he was sent down to Omaha in the Class A Western League. After batting .315, he went back to school for his senior year. But when he graduated in June 1951, the Cardinals refused to raise his $300 monthly salary. He became a holdout. He found a better-paying job as the Aggies’ freshman baseball coach and began work on his master’s degree in educational administration. Good thing; that summer he met Bettye Knowles, a fellow student who soon became his wife.

Moon reported to Omaha for 16 games at the end of the season, then resumed his classes. Master’s degree in hand, he was back on the same Class A field in June 1952. He was now a full-time ballplayer. Elevated to Triple-A Rochester the following year, he hit .307/.382/.504, but that was not enough to merit another promotion; he was ticketed for Rochester again in 1954.

Moon had had enough of the minors. He showed up uninvited at the Cardinals’ major-league spring-training camp in St. Petersburg, Florida. Manager Eddie Stanky didn’t kick him out. Instead, he gave him ample playing time. Moon had a head start on his teammates because he had played winter ball in Venezuela. “I gambled on everything,” he said. “If I hit a single I’d go for two. If I had two I’d go for three. I tried to catch everything I had the slightest chance for in the outfield. I ran every place.”3

After he played several exhibition games in right field, a writer suggested Moon was being groomed to replace Slaughter eventually. One day Slaughter paused at Moon’s locker. “Don’t worry,” the veteran said. “You’re not going to take my job.”4 But eventually turned out to be now. When Slaughter was traded just before Opening Day, the rookie took his place in the starting lineup.

The 1954 Cardinals, led by Stan Musial, scored the most runs in the National League, but weak pitching dragged them down to sixth place. Playing center field and batting leadoff, Moon had a pair of five-hit games and a 13-game hitting streak. A strong July boosted his average as high as .343. He was contending for the batting title before he swooned in September, when he was diagnosed with a stomach ulcer. He finished in the league’s top 10 in runs, hits, triples, and steals. He garnered 17 of 24 votes in the sportswriters’ Rookie of the Year balloting to 4 for Banks, 2 for Milwaukee pitcher Gene Conley, and 1 for Aaron. Musial, who had become a mentor, said, “Moon is the best rookie hitter I ever saw because of his consistency against all types of pitching.”5

For the next three years the Cardinals achieved a winning record only once, when they finished second to the Milwaukee Braves in 1957. Moon established himself as a productive hitter and a hustler in the Slaughter tradition. Sports Illustrated put him on its cover in April 1957, calling him “The Hope of St. Louis.” Manager Fred Hutchinson said, “I wish all my players were like him.”6 That publicity, plus a 24-game hitting streak in May, earned Moon his first All-Star selection. His first four seasons produced a .298 batting average and an .835 on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS).

In May 1958 Moon was chasing Orlando Cepeda’s fly ball when he collided with Joe Cunningham, a first baseman who had to play outfield so the aging Musial could play first. Moon hurt his elbow when Cunningham fell on top of him. He never regained his batting stroke or his regular job. His average fell to .238. The front office publicly blamed the failures of Moon and the fading slugger Del Ennis for the club’s fifth-place finish. Still, Moon remained a Hutchinson admirer: “I loved Freddy Hutchinson. If you couldn’t play for him, you couldn’t play for anybody.”7

In May 1958 Moon was chasing Orlando Cepeda’s fly ball when he collided with Joe Cunningham, a first baseman who had to play outfield so the aging Musial could play first. Moon hurt his elbow when Cunningham fell on top of him. He never regained his batting stroke or his regular job. His average fell to .238. The front office publicly blamed the failures of Moon and the fading slugger Del Ennis for the club’s fifth-place finish. Still, Moon remained a Hutchinson admirer: “I loved Freddy Hutchinson. If you couldn’t play for him, you couldn’t play for anybody.”7

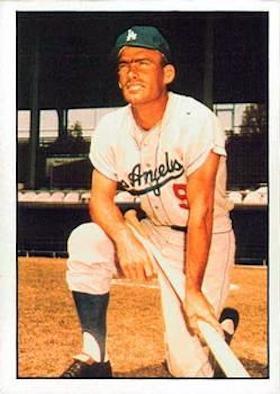

The Cardinals traded Moon to the Los Angeles Dodgers in December. He was not happy; he and Bettye had three children and had bought a home in St. Louis, because he wanted to be with his family year-round. He was insulted when he learned that it wasn’t even a straight-up swap. The Dodgers sent their disappointing outfielder Gino Cimoli to St. Louis, and the Cardinals had to part with a pitcher, Phil Paine, along with Moon. Explaining the deal, Dodgers vice president Fresco Thompson said, “Moon’s got 80 percent ability but gives you 90. Cimoli’s got 90 percent ability but gives you 75.”8

The Dodgers had moved to Los Angeles in 1958, attracted huge crowds, and belly-flopped into seventh place. The Boys of Summer had gotten old overnight. Moon stepped into a crowded outfield, but one filled with question marks. Duke Snider had a bad knee. Carl Furillo, 37, could no longer play every day. Don Demeter hadn’t hit in his first 46 big-league games. Bonus baby Ron Fairly was less than a year removed from leading the University of Southern California to victory in the College World Series. General manager Buzzie Bavasi had promised to overhaul the roster for 1959, but Moon was his only significant acquisition.

The club was struggling to stay above .500 in June when Bavasi delivered the overhaul—from within his vast farm system. He called up pitchers Roger Craig, whose sore arm had been given up for dead, and Larry Sherry, whose minor-league record was below mediocre. In desperation, a nine-year minor leaguer, Maury Wills, was given a chance to take over shortstop from Don Zimmer. But all three had reinvented themselves. Craig, after losing his fastball, made himself into a sinker-slider pitcher. Sherry learned a slider from his brother Norm, a catcher in the Dodgers system. Wills, encouraged by Triple-A manager Bobby Bragan, had become a switch hitter.

Moon started both 1959 All-Star Games, the only times he was chosen as a starter. He, second baseman Charlie Neal, and third baseman Jim Gilliam were the Dodgers’ only everyday players. Manager Walter Alston juggled the other positions among the flawed and infirm. Los Angeles hung into a three-way pennant race with the defending champion Braves and the young San Francisco Giants. On the morning of August 30, San Francisco held first place, with Los Angeles and Milwaukee three games behind.

The Dodgers and Giants were meeting at the Los Angeles Coliseum, the mammoth football stadium that was the Dodgers’ cartoonish temporary home. A 40-foot screen marked the boundary in the shortened left field; the right-center fence appeared to be in another county. Pitcher Stan Williams said, “It was 251 feet to left field and four miles to right field.”9 The Giants took a 6-5 lead into the bottom of the ninth. After Neal reached on an error, Moon pinged a liner off the left-field screen. The ball bounced around the outfield while Neal raced home with the tying run and Moon wound up at third. Moon scored the game winner on a walk-off error by the Giants’ rookie first baseman, Willie McCovey.

The next night the Dodgers’ wild young lefty, Sandy Koufax, struck out 18 Giants, tying Bob Feller’s major-league record for a nine-inning game. The score was 2-2 when Los Angeles came to bat in the bottom of the ninth. The Dodgers put two men on, with Moon due up. In the on-deck circle he told teammate Norm Larker, “You can take a seat, Norm. I’ve got this game won. Man, I’m going to hit one out of here.” Moon valued his reputation as “a humble man of God”; he was the last one you’d expect to call his shot. Now he lofted a game-winning homer over the screen. He said his former teammate Stan Musial had advised him to master an inside-out swing so he could take advantage of the short left field.

The back-to-back walk-off victories boosted Los Angeles to within one game of the first-place Giants. As the race tightened in September, Moon seemed to be in the midst of every Dodger rally. On the 11th he hit three home runs in a doubleheader sweep of the Pirates. In the next game he sliced another fly ball toward the screen. The Soviet Union had just landed the first unmanned probe on the moon, and Dodger broadcaster Vin Scully proclaimed, “It’s another moon shot.” Moon’s homer was his fourth in seven at-bats. The next day, against the Braves, he hit another one, this time to right field. Two days later he banged his sixth homer in six games.

In the last 25 games of the regular season, Moon slammed eight home runs with a 1.081 OPS. Wills, who had entered September batting .215, hit .453/.482/.547 in the last two weeks. Roger Craig posted a 1.01 ERA in the final month of the regular season, and Larry Sherry 1.78. The Dodgers passed the Giants on the 19th after sweeping three games in San Francisco. Los Angeles and Milwaukee finished tied for first place, and the Dodgers won two straight playoff games to claim an unlikely pennant. On paper, they were by far the weakest of the three contenders.

“That was the best managing job I’ve ever seen anywhere,” Moon said decades later. “Alston, to me, was the perfect manager for a major-league baseball team. Quiet, a gentleman [who] understood the game and understood people.”10

Alston returned the compliment: “Winning this pennant was a team victory. But of all the players, I’d have to say Moon was the most consistent.”11 Moon batted .302/.394/.495, the best season of his career so far, with 19 home runs. His 11 triples tied teammate Charlie Neal for the league lead. He finished fourth in the Most Valuable Player voting behind Banks, Eddie Mathews, and Aaron.

The Dodgers, exhausted by the tension of the pennant race, collapsed in the first game of the World Series, losing 11-0 to the AL champion White Sox. Los Angeles took a 4-2 lead into the eighth inning of Game Two, when the White Sox put two men on and Al Smith slammed a drive toward Moon in Comiskey Park’s left field. Moon faked a catch, freezing the runners as the ball hit the wall. A relay from Moon to Wills to catcher John Roseboro cut down Chicago’s Sherm Lollar, who was carrying the tying run. Yankees manager Casey Stengel, in the unaccustomed role of newspaper columnist, called it the pivotal play of the Series.

The Dodgers went on to win the championship in six games, with Moon contributing a two-run homer in the finale. He used his $11,000 Series check to buy a home on two acres in the San Fernando Valley, where his neighbors included teammate Duke Snider and another famous Duke, John Wayne, as well as the singing cowboy Tex Ritter. Moon’s son, Wally Joe, became close friends with Ritter’s son John, the future star of the TV sitcom Three’s Company. Sandy Koufax, Moon’s roommate, gave the children a cocker spaniel named Dr. Pepper.

Putting down roots in Southern California, Moon established the Wally Moon Baseball Camp for boys and invested in a sporting goods store. Like many of his teammates, he took a turn in front of cameras, playing a sheriff in an episode of the TV western Wagon Train. He represented the Methodist Church on the board of regents of the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California.

Baseball was still Moon’s number-one job, and he went at it with a grim competitiveness. He stayed up for hours to unwind after night games, with Bettye sitting beside him and sometimes serving his dinner at 3 A.M. He enjoyed two more strong seasons, winning a Gold Glove in 1960 and leading the league with a .434 on-base percentage in ’61 while putting up a career-high .328 batting average. When the new Dodger Stadium opened in 1962, Moon was glad to leave the Coliseum behind. Despite his success in the monstrosity, he said he was not comfortable there. “I changed my batting stance and my fielding habits and never played the way I was trained to play.”12

By 1962 the Dodgers had assembled a 25-and-under outfield of Frank Howard, Tommy Davis, and Willie Davis. Moon, playing first base, twisted a knee when he tripped over his mitt fielding a groundball. He joined Snider on the bench. General manager Bavasi said the club couldn’t afford two expensive bench warmers; Moon was reportedly the highest-paid Dodger at $42,000, with Snider making a reported $38,000. Snider, a Dodger for 16 seasons, was sold to the New York Mets on April 1, 1963. Moon said he should have been the one to go.

In 1965, after four years as a part-time player, Moon was an afterthought at age 35. Asked if he was unhappy with his role, he replied, “You have to admit, it still beats picking cotton.”13 He ended his career by grounding out to second base as a pinch-hitter in the sixth game of that fall’s World Series. Bavasi offered to let him go to Japan, where a big contract was waiting, but Moon decided not to uproot his family, which had grown to one son and four daughters.

Starting in his rookie year, Moon was elected his team’s player representative throughout his career. The Players Association was a toothless organization that petitioned for better clubhouse and travel conditions but was primarily concerned with the pension plan and health and life insurance. “We never described ourselves as a union,” Moon said. When clubs began traveling by air extensively in the 1950s, he discovered that the management took out life insurance policies on players—but the team, not the player’s family, was the beneficiary. The pension for a 10-year veteran amounted to less than $100 a month. Playing a second All-Star Game, from 1959 through 1962, was a move to fatten the pension fund.

The year after Moon retired, the players hired a Steelworkers union economist, Marvin Miller, as the association’s first full-time executive director. Miller never ducked a confrontation and transformed the association into the most successful labor organization in American history. Moon praised Miller’s accomplishments, but not his style: “I was not a Marvin Miller fan. The thought of a strike never entered my mind.”14

Leaving his playing career behind, Moon returned to the college ranks as head baseball coach and athletic director at John Brown University, a tiny Christian school in Siloam Springs, Arkansas. (The university is named for a preacher, not the abolitionist.) With about 500 students, John Brown played in the small-college National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA). Bettye was delighted to move closer to home, though the older children were not. She put her teaching degree to use at Siloam Springs High School.

Moon coached the Golden Eagles for 10 years, with one detour. He took a sabbatical in 1969 to serve as hitting coach for the expansion San Diego Padres, where Bavasi was part-owner. He wanted to get back into professional ball with hopes of working his way up to a manager’s job. But he returned to the university after one season because he didn’t like being away from his family.

John Brown, with its strict Christian focus and out-of-the-way location, couldn’t compete for top-level recruits. Still, Moon put together winning teams in his decade as head coach. Seven of his players went on to professional ball, though none reached the majors. Moon took on additional responsibilities as a university vice president, concentrating on fundraising. He was active in Democratic Party politics and served as statewide chairman of a campaign to modernize Arkansas’ county governments.

In the fall of 1976, Bobby Bragan, a former Dodger player and coach who was president of the Texas League, called to pitch a proposition straight out of left field. He wanted Moon to buy the league’s San Antonio franchise. Moon told him that small-college coaches didn’t get rich, but Bragan put on the hard sell. The club, a Dodger affiliate, had an experienced general manager in place and the city was preparing to build a new ballpark. This gold mine could be had for just $50,000.

Moon bought the gold mine and got the shaft. The GM quit before the new owner’s first opening day in 1977. Moon had planned to be an absentee owner but had to take over to protect his investment. He installed his 23-year-old son, Wally Joe, as general manager and learned his way around San Antonio by hawking tickets. There weren’t many takers; attendance in his first season totaled only 53,000. The San Antonio Spurs, who had just joined the NBA, were soaking up all the local sponsorship dollars. The city never built a ballpark, so the club had to share a college stadium in a sketchy neighborhood. After some fans’ tires were slashed, Moon hired a teenage gang to guard the parking lot and the vandalism mysteriously stopped. Moon figured he had lost $100,000 by the time he sold the team after three years.

He had moved his family to Texas, eventually settling in Bryan. He worked in real estate in the 1980s but still yearned to return to the majors as a manager or coach. In 1987 his friend Roland Hemond, who headed the Yankees farm system, hired Moon as manager of the Class A Prince William (Virginia) club. He was fired midway through his second season and moved on with Hemond to the Orioles. Moon managed the Frederick (Maryland) Keys to the championship of the Class A Carolina League in 1990, but left after the Keys sank to last place the next year.

Moon served as a minor-league hitting instructor in the Baltimore organization until he retired in 1995, soon after Bettye contracted Parkinson’s disease. Moon said, “The Lord has blessed us.”15

He died at the age of 87 on February 9, 2018, in Bryan, Texas

Notes

1 United Press, Boston Traveler, April 14, 1954, 35.

2 Wally Moon with Tim Gregg, Moon Shots (San Antonio, Texas: Moon Publishing, 2010), 336. Unless otherwise credited, all quotes from Moon are from this book.

3 Robert Creamer, “The Hope of St. Louis,” Sports Illustrated, April 22, 1957, online archive.

4 Ibid.

5 United Press, Pittsburgh Press, December 20, 1954, 23.

6 Creamer, “The Hope.”

7 Author’s telephone interview with Wally Moon, January 28, 2015 (Hereafter Moon interview).

8 Lee Greene, “The Trade That Made the Dodgers,” Sport, January 1960, 31.

9 Danny Peary, ed., We Played the Game (New York: Black Dog & Leventhal, 1994), 393.

10 Moon interview.

11 Greene, “The Trade,” 87.

12 Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, March 7, 1962, in Moon’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York..

13 Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, August 9, 1965, 26, in HOF file.

14 Moon interview.

15 Moon interview.

Additional source

Roger Kahn, A Season in the Sun (New York: Harper and Row, 1977).

Full Name

Wallace Wade Moon

Born

April 3, 1930 at Bay, AR (USA)

Died

February 9, 2018 at Bryan, TX (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.