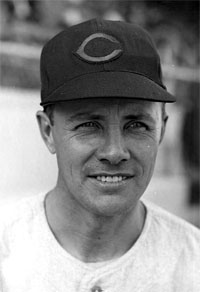

Lonny Frey

The Cincinnati Reds of the 1930s were the National League’s weakest team, logging five last place finishes from 1931 to 1937. That futility ended when Bill McKechnie took over as the Reds’ manager in 1938. McKechnie led Cincinnati to back-to-back pennants in 1939 and 1940 and a world championship in 1940.

The Cincinnati Reds of the 1930s were the National League’s weakest team, logging five last place finishes from 1931 to 1937. That futility ended when Bill McKechnie took over as the Reds’ manager in 1938. McKechnie led Cincinnati to back-to-back pennants in 1939 and 1940 and a world championship in 1940.

Although several key players were in place when McKechnie arrived, including Frank McCormick, Paul Derringer, and Ernie Lombardi, it was the 1938 additions of pitcher Bucky Walters and second baseman Lonny Frey that turned the Reds from also-rans into champions. Walters was the league’s best pitcher in 1939 and 1940, while Frey helped to anchor one of the best defensive infields ever.

Linus Reinhard Frey (pronounced Fry) was born on August 23, 1910, in St. Louis, Missouri, the second of Frank and Louise (Scherer) Frey’s three sons. They named him for St. Linus (considered St. Peter’s successor as pope), though hardly anyone called him Linus. To his mother, he was Liney; friends knew him as Lonny or Lonnie; and newspapers sometimes called him Junior, a named he disliked.

The Freys were a close-knit, solidly middle-class German Catholic family. Frank drove a truck for the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company while Louise stayed home and looked after the children in the modest brick house they owned in the northwestern part of the city. Although Frey was bright and curious, his formal education lasted only through grammar school. Later he attended a business school to learn stenography, but for the most part he was his own teacher. He became a voracious reader; when he couldn’t find a book or magazine that held his interest, he read the dictionary. “There was not a word he couldn’t spell,” his son Thomas marveled.1

Initially, soccer was his sport. He enjoyed baseball and grew up a rabid St. Louis Cardinals fan, but never thought very seriously about making a living at the game. As Frey entered his twenties, he secured a job as a secretary at a meat-packing plant. He played sandlot baseball in the evenings and on weekends, but that was as far as it went.

Then one day in 1931, he arrived at work to find a layoff notice. In the throes of the Great Depression, Frey and the other junior staffers were out of a job. After weeks of searching for work unsuccessfully, he decided to attend an open tryout with the Cardinals. Frey needed a job and baseball was one of his few marketable skills.

Within a few years, Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey would accumulate more prospects than he knew what to do with. But Rickey’s scouts judged Frey too scrawny and passed on signing him. (Frey eventually filled out to five feet ten and 160 pounds.) Harvey Albrecht, Frey’s sandlot coach and a former Minor League player believed his young shortstop deserved another look. Albrecht asked his onetime manager Jimmy Hamilton, who was now a scout for Nashville of the Southern Association, to take a look at Frey. Hamilton did and signed him to a contract, complete with an invitation to spring training in 1932. Albrecht matched Frey not only with a job, but also a bride. His sister Mary Ann became Frey’s wife of forty-seven years and mother to his four sons.

Frey batted a combined .288 in 1932, splitting the season between two Class B leagues: York (Pennsylvania) of the New York-Pennsylvania League, and Montgomery (Alabama) of the Southeastern League. In August 1933, the twenty-three-year-old Frey was hitting a solid .294 for Nashville of the Class A Southern Association, when he was summoned to join the lowly Brooklyn Dodgers, who were desperate for infield help after a string of injuries.

With his wiry frame and boyish face he could have passed for a high-school student. Max Carey, Brooklyn’s manager, gave Frey the once-over and exclaimed, “You’re just a kid! You’re no bigger than a minute.”2 But Frey’s matter-of-fact confidence belied his callow appearance and unassuming demeanor. “I didn’t come up here to go back,” he declared to a reporter.3

He immediately became Brooklyn’s starting shortstop and maintained a grip on the position for the next three-plus seasons. Frey hit well for a shortstop, flashing occasional power and demonstrating a good eye. In 1935 he ranked in the top ten in the National League in extra-base hits and walks. He didn’t steal many bases—few in that era did—but he was a fast, aggressive runner, unafraid to take an extra base or crash into a pivot man. His quiet, professional approach earned him the post of team captain prior to the 1936 season.

On the downside, Frey was a dreadful defender. “Shortstop was not my position as far as pro ball was concerned,” he admitted. He led the majors in errors in both 1935 and 1936, and his range was adequate at best. Frey lacked the arm strength required of a big-league shortstop so he was always in a rush to scoop up the ball and get it away as quickly as possible. The result was an endless mess of misplayed grounders and off-target throws.

Dodgers fans turned on Frey in 1936, after he committed fourteen errors in the Dodgers’ first twenty-seven games. “You couldn’t believe the booin’ I’d get in Brooklyn. I couldn’t get the ball to first base.”4 His misadventures turned him into a punch line. Author Roger Kahn related one quip about Frey that made the rounds: “There’s an infielder with only one weakness. Batted balls.”5

People made Frey sound like a man teetering on the edge of an emotional breakdown. In May, manager Casey Stengel publicly questioned his shortstop’s guts, saying, “Lonny is sensitive about the way those fans in Brooklyn holler and when they jumped on him he went to pieces.”6 Headlines read, “Dodgers’ Defeat Breaks Frey’s Spirit” and “Dodgers’ Captain Unable to Stand Riding from Fans.”7 A teammate questioned how much more Frey could take: “When they roast a ballplayer like that a fellow might just as well root to be traded.”8

It is possible Frey had thicker skin than he got credit for. Although some writers claimed he hit better on the road than in Ebbets Field in front of his critics, the opposite actually was true. As for his defense, that was just as wretched in Brooklyn as it was anywhere else. Frey insisted the remnants of a springtime bout with tonsillitis bothered him more than the loudmouths in the bleachers. “It wasn’t the Brooklyn fans booing me that affected my play,” he said. “I’ve seen that written but it was just because my health was so bad. I never felt right all year. I felt like lying down and taking a week off. It was that poison in my system from the throat infection I had.”9

In December 1936 the Dodgers dealt Frey to the Chicago Cubs for infielder Woody English and pitcher Roy Henshaw. Frey was happy to get away from Stengel. “I could never understand what Stengel was saying,” he said years later. “I had him long enough. All he thought of was himself. All he did was tell stories to reporters. He didn’t know what he was doing.”10

On the other hand, he was fond of Brooklyn, despite the abuse. “When he got traded he kind of thought that was the end of the world,” according to Thomas Frey. He was comfortable in the neighborhood he lived in and appreciated the enthusiasm of the fans, even though he wasn’t their favorite. “What a place that will be to play ball if those directors ever straighten the club’s affairs out or if someone can buy the whole outfit,” he mused.11

Frey played in seventy-eight games for Chicago in 1937, filling in admirably at four positions. In February 1938 the Cubs sold him to Cincinnati. He couldn’t have landed in a more perfect spot. For Frey, Bill McKechnie was everything Stengel was not. “He could look at a fellow and pick out his flaws and correct them.”12

McKechnie’s solution for Frey’s defensive troubles was to shift him to second base, a position he had played in only forty-seven Major League games. Within two years Frey had transformed himself into the league’s pre-eminent defensive second baseman. His newfound success surprised everyone but him. “I thought I could play regular anywhere,” he said. “That’s the confidence I had in myself.”13

Frey’s best offensive day of the 1938 season came in a June 26 doubleheader against the Phillies in the Baker Bowl. After going 3-for-5 with a double in the first game, he went 5-for-5 with two triples and three RBIs in the nightcap.

Frey and his infield mates were a colorful bunch. Third baseman Bill Werber came over in 1939 and decided the group needed a nickname because, as he put it, “The ballclub was a little deadass.”14 They became the Jungle Club. Frey had birthmarks all over him, so Werber took to calling him Leopard. Shortstop Billy Myers was Jaguar, first baseman Frank McCormick became Wildcat, while Werber tagged himself with Tiger.

Werber and Frey grew particularly close. Both were thoughtful and intelligent men, homebodies at heart; boozing and chasing women held no appeal. They killed time at the movies and even attended Mass together, with Werber tagging along even though he wasn’t Catholic. The two friends exchanged cards and phone calls into their nineties.

The 1939 season was Frey’s best as he helped lead the Reds to the National League pennant. At the start of the season, McKechnie persuaded him to forget switch-hitting and bat exclusively left-handed. He also suggested that Frey try to pull the ball more. Frey responded by hitting .291 with eleven home runs, a league-leading twenty five sacrifice hits. He made the first of his three appearances in the All-Star Game, where he knocked in the National League’s only run. Arthur Patterson of the New York Herald Tribune was floored. “Anyone predicting this spring that Linus Frey not only would play a full game at second base in the All-Star Game but also avert a shutout for the National League . . . would have been gently led away to the nearest psychopathic ward and barred from the press box for life,” he wrote.15 However, the year ended with a thud for Frey—an 0-for-17 collar in the World Series, which the New York Yankees swept in four games.

Frey led the league with twenty-two stolen bases in 1940, and he was fourth in runs scored (102) and sixth in walks (80). Defensively, he led all National League second basemen in games played, assists, chances, putouts, double plays, and fielding percentage.

The Reds made it back to the World Series in 1940 and defeated the Detroit Tigers in seven games to capture their first title since 1919. “We were so confident,” boasted Frey. “It was almost ridiculous to say we were going to get beat.”16 Frey sat out most of the Series with a toe injury; he batted twice as a pinch hitter and made one late-game appearance at second base.

Frey remained a steady, reliable presence in the Reds’ lineup through 1943, when Uncle Sam beckoned. Private Frey spent two years stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, where he batted .450 as his Fort Riley Centaurs took the Western Victory League championship. However, when he returned to Cincinnati at the age of thirty-four in 1946, something was missing. “I just didn’t have it anymore. Two years in the service and you lose it. … I was just too old, I guess,” he said.17

With his skills declining, Frey bounced from the Reds back to the Cubs briefly, and then in June 1947 to the Yankees. As the story goes, he arrived early in the morning at the Yankees’ hotel in Philadelphia, immediately phoned manager Bucky Harris and announced, “I’m here.” Harris grumbled, “I am delighted,” hung up, and went back to bed. Frey appeared in just twenty-four games for New York that season, mostly as a pinch runner or pinch hitter, and drove in a run in Game Six of the Yanks’ World Series victory over Brooklyn.

Frey made one pinch-running appearance for the Yankees in 1948, then was released in May. He signed with the New York Giants, spent half the season with their Minneapolis farm team, and was released after the season. He played for Buffalo in 1949 and Seattle in 1950 and retired after the 1950 season. He finished his 14-year big league career with 1,482 hits and a .269 batting average in 1,535 games.

Frey discovered that life in the Northwest suited his family perfectly. “We rented a house on Lake Washington. [My sons] learned how to swim, they learned how to fish, [and] they learned how to drive a motorboat.”18 The Freys sold their home in suburban St. Louis and relocated to Washington.

Neither coaching nor scouting interested him in the least. “I had enough traveling. I wanted to get out of it,” he said. He spent a number of years at a large Seattle sporting-goods store, sold luggage for a while, and then retired, content to toil part-time as a handyman at his church.

As an old man, Frey relished the constant stream of autograph requests that came his way, and enjoyed attending both college and professional ballgames. On his ninetieth birthday, the Seattle Mariners invited him to throw out the opening pitch at a game at Safeco Field. “He was a warm, very down-to-earth guy,” said Pacific Coast League historian Dave Eskenazi. “He shared a number of entertaining baseball anecdotes, mainly about his old teams and teammates. I remember him telling me that Ernie Lombardi hit the ball harder than anyone else he’d seen, and he’d seen them all.”19

Frey was ever the athlete—walking, biking, ice skating, and bow-hunting. After Mary’s death in 1982, he moved to a small house in Hayden, Idaho, to be closer to his children. There, at the age of seventy-two, he took up skiing for the first time. And no one could get him off that bicycle. Even when he was ninety-five, after two knee replacements and quadruple-bypass surgery, he pedaled all over town.

A stroke finally slowed Frey down and forced him into an assisted living facility. When he died, in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, on September 13, 2009, at the age of ninety-nine, he was the second oldest living major leaguer; the oldest was his good friend Billy Werber. Frey and his wife are buried in Bellevue, Washington. Asked a few years before his death to name the one highlight of his career, he couldn’t do it. “Every day was a highlight.”20

This biography is included in the book “Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by Lyle Spatz. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Kahn, Roger, The Boys of Summer, 1972; reprint (New York: HarperCollins, 2006).

Mulligan, Brian, The 1940 Cincinnati Reds (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2005).

Vitti, Jim, Chicago Cubs: Baseball on Catalina Island (Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2010).

Werber, Bill, and C. Paul Rogers III. Memories of a Ballplayer: Bill Werber and Baseball in the 1930s (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2001).

Brooklyn Eagle

Brooklyn Times-Union

Charlotte Magazine

Cincinnati Enquirer

New York Sun

New York World-Telegram

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2002.

Bedington, Gary, “Lonny Frey,” Gary Bedington’s Baseball in Wartime, 2008, Web, accessed August 26, 2011.

Lonny Frey, oral history interview, August 27, 1991, Society for American Baseball Research Oral History Collection.

Author telephone interview with Thomas Frey, August 29, 2011.

Thomas Frey telephone conversations with Thomas Bourke, September 20 and September 27, 2011.

Notes

1. Frey, Thomas, telephone interview with author, August 29, 2011.

2. Frey, Lonny, oral history interview, August 27, 1991, Society for American Baseball Research Oral History Collection.

3. New York World-Telegram, August 30, 1933.

4. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 23, 2005.

5. Kahn, Roger, The Boys of Summer, 1972; reprint, New York: HarperCollins, 2006, p. xiii.

6. New York Sun, May 27, 1936.

7. New York Sun, June 9, 1936; Brooklyn Times-Union, May 25, 1936.

8. Frey, Lonny, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum player file, undated article.

9. Frey, Lonny, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum player file, undated article.

10. Frey, Lonny, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum player file, undated article.

11. Frey, Lonny, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum player file, undated article.

12. Frey, Lonny, oral history interview, August 27, 1991, Society for American Baseball Research Oral History Collection.

13. Frey, Lonny, oral history interview, August 27, 1991, Society for American Baseball Research Oral History Collection.

14. Sports Collectors’ Digest, June 17, 1994, quoted in Mulligan, Brian, The 1940 Cincinnati Reds, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2005, p. 36.

15. Frey, Lonny, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum player file, undated article.

16. Frey, Lonny, oral history interview, August 27, 1991, Society for American Baseball Research Oral History Collection.

17. Frey, Lonny, oral history interview, August 27, 1991, Society for American Baseball Research Oral History Collection.

18. Frey, Lonny, oral history interview, August 27, 1991, Society for American Baseball Research Oral History Collection.

19. “Former major-league Lonnie Frey Dies,” Seattle Times, September 16, 2009.

20. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 23, 2005.

Full Name

Linus Reinhard Frey

Born

August 23, 1910 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

September 13, 2009 at Coeur d'Alene, ID (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.