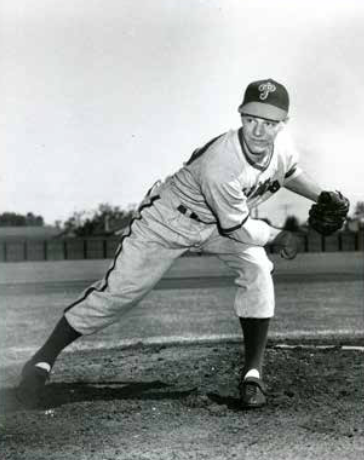

Paul Stuffel

Right-hander Paul Stuffel had a reputation as one of the hardest-throwing pitchers of his generation. As a Philadelphia Phillies prospect in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Stuffel overpowered batters in several low- and mid-level minor leagues, but also struggled controlling his heater. While pitching for the Schenectady (New York) Blue Jays in the Class-A Eastern League in 1951, Stuffel tossed his second career no-hitter, striking out 20 and walking 10. “Yeah, I walked some batters. I walked a lot of ’em,” he told the author.1 “But it didn’t bother me. A lot of being wild is making others think you’re wild. When I warmed up, sometimes I threw the ball and it hit 10 feet in front of the plate. Other times I threw the ball over the catcher’s head. I put fear in the batters before they came to the plate. You gotta have respect.”

Stuffel debuted with the Phillies as a late-season call-up in 1950, and pitched batting practice in the World Series. “I hated anybody with a bat,” said Stuffel with a laugh, but with a noticeable air of sincerity. “Those guys were my enemies. I didn’t bust the ball in there as hard as I could during warm-ups. When I got to the mound, the adrenaline kicked in and I could throw hard.” Though his major-league career consisted of just seven appearances and one victory over parts of three seasons, Stuffel was proud to call himself a big leaguer.

Paul Harrington Stuffel was born on March 22, 1927, in Canton, about 60 miles south of Cleveland in northeastern Ohio. His parents were Pete, originally from Nebraska, and Ethel (Blakoe) Stuffel, who was born in England and immigrated to Ohio via Canada. Paul was the second of four children, preceded by Dorothy, and followed by Elaine and David. A bartender at a local tavern, Pete served as a runner in World War I and was severely injured by friendly fire. At one point physicians feared that both of his legs would be amputated. He was hospitalized for two years in Europe and doctors eventually saved his legs, but he was permanently disabled and walked with a pronounced limp thereafter, hobbled by a heavy steel leg brace. A lifelong baseball fan, he wanted both of his sons to become big-league pitchers, and despite his physical limitations worked tirelessly to achieve that goal. “My father and I used to play baseball together all the time beginning at about the age of 5 or 6,” said Stuffel. “Because my dad couldn’t walk that well, if I threw a pitch and he couldn’t reach it, I had to get it. So I learned to throw accurately.” The two spent hours in a field near their home throwing the ball, but as Paul grew and became stronger, it was clear that his father could no longer serve as his designated catcher and de-facto coach. When Stuffel was about 15, he began to throw to and work out with neighbor Howard Griffin, a former amateur catcher and local police officer. Griffin realized that the hard-throwing right-hander was not the run-of the-mill youngster wanting to be the next Bob Feller.

Paul began playing in organized leagues when he was about 16 years old. He starred as a pitcher and occasional shortstop for coach Junie Ferrell at Lincoln High School in Canton, tossing a no-hitter in his junior year and winning 15 of 17 decisions in his senior year.2 He spent the winter months building up his arm strength by throwing indoors. Stuffel also played for W&R Sports in Canton’s competitive summer and fall amateur sandlot leagues. He gained invaluable experience against mature players, many of whom had played in Organized Baseball, such as Vince Shupe and Tim Triner in the Boston Braves organization. The youngster established a reputation as a strikeout artist, facing regional amateur and semipro teams and even traveling amateur Negro teams.

Stuffel graduated from high school in 1945 just as hundreds of major leaguers and literally thousands of minor-league players were gradually returning to Organized Baseball after fulfilling their military commitments. Teams, both major and minor, were suddenly confronted with an unusual dilemma: too many players. The minors had contracted to just 12 leagues in 1945, down from 41 in 1941, and would ratchet up to 42 in 1946. Growing up as a fan of the St. Louis Cardinals and their exceptional pitching staffs during the war years, the 18-year-old Stuffel had a stroke of luck when the Redbirds conducted a three-day tryout camp in Canton. “Tony Kaufmann, the ex-pitcher and Cardinals scout, ran it,” explained Stuffel. “Afterwards he told me that he’d like to sign me, but the Cardinals had an unwritten rule that they wouldn’t sign players who were going into the service. And I already had my papers to report a month later.” Just when Stuffel thought he had lost his opportunity to pursue a career in professional baseball, he got an unexpected second chance. “The Phillies came to town about two weeks later and had a tryout camp,” said Stuffel with noticeable excitement 70 years later. “The trials took place over a few days at City Field in Canton. Eddie Krajnick ran it, and he signed me, too. I didn’t get a bonus. I got a promise of a 30-day tryout with the Phillies after I got out of the service.” Krajnik also signed such Phillies stalwarts as Richie Ashburn and Stan Lopata, and helped ink Robin Roberts. Five years later, in 1950, Stuffel’s brother, Dave, signed as a pitcher with the Cleveland Indians organization.

Stuffel’s euphoria at signing a professional baseball contract in early August 1945 did not last long. “I was inducted into the Army on August 14 at the Cleveland Induction Center,” he said. “About two hours later, the public address announcer came on and announced that the Japanese had just surrendered.” The 18-year-old was sent to Fort Robinson in North Little Rock, Arkansas, where he was in basic training for 27 weeks, and was later deployed to Germany in early 1946. “I was in an engineering outfit attached to the 3rd Army. We were stationed in Schwandorf (in southern Germany) and one day I saw a notice on a bulletin board that there were tryouts for a regimental baseball team in Regensburg.” Stuffel recalled that the quality of baseball was good, with the vast majority of players having some experience in Organized Baseball. According to one report, Stuffel amassed 256 strikeouts while hurling for the 26th Infantry Division, and led them to the ETO championships in Nuremburg.3

After his discharge, Stuffel enrolled at Kent State University, located about 40 miles from his hometown, on the GI Bill. In early 1947 he received a letter from the Phillies instructing him to report to their camp in Clearwater, Florida. “My professors told me to finish my papers and I could get credit for the term, but I was so excited and more interested in baseball,” said Stuffel. “I reported to spring training and never went back to college.”

“I was excited to be with big leaguers,” said Stuffel, explaining that he had finally realized his boyhood dream. “I hadn’t even pitched a game in Organized Baseball. These guys were my idols,” and he mentioned names such as pitchers Schoolboy Rowe and Dutch Leonard and former Cardinals hitters Harry Walker and Emil Verban, who were now with the Phillies. But he also experienced something that bothered him. “The Boston Red Sox were in town and Ted Williams was standing on the first-base line,” he said. “All the younger Phillies players were hugging and kissing him, and talking to him. And I thought, ‘what are they doing?’ That guy was our enemy. I could never get over that.”

Stuffel began his 11-year odyssey in professional baseball in 1947 with Salina (Kansas) in the Class-C Western League. Described as an “ace fireballer” by the Associated Press, Stuffel was the hardest-to-hit pitcher in the league, surrendering just 6.5 hits per nine innings.4 However, he was also plagued by wildness, issuing 127 walks in 181 innings. He won 13 of 23 decisions, and teamed with Bubba Church (21-9) and Arthur Haley (22-5) to lead the Blue Jays to the regular-season title before being upset in the playoffs.

After a look-see with the Phillies in spring training in 1948 and 1949, Stuffel was assigned to Terre Haute (Indiana) in the Class-B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa (Three-I) League each year. En route to a 13-11 record in 1948, Stuffel tossed a perfect game to defeat the Davenport Pirates, 2-0, on August 27.5 He finished second in strikeouts (217) and first in walks (148) in 190 innings. Nicknamed “Swifty” by Terre Haute sportswriter Forrest Gardenwire, Stuffel had a breakout season in 1949.6 He tossed a one-hitter, two two-hitters, a three-hitter, and eight four-hitters, and struck out a league-leading 288 batters in 252 innings, yet was a .500-pitcher (13-13). The hard-thrower admitted that he exasperated his managers by his lack of control. In both seasons with Terre Haute; he surrendered more walks than hits per nine innings. Standing 6-feet-2 and weighing about 185 pounds, Stuffel was a big pitcher for the era. Rugged and durable, he led the Three-I league with 19 complete games in 1949. One of those was described as a “herculean” effort, a 14-inning complete game and with16 strikeouts on two days’ rest to defeat Davenport in July.7 Though pitch counts were not kept, Stuffel thought that he regularly threw in excess of 150 pitches in a game.

Both seasons in Terre Haute had frustrating conclusions for Stuffel. He was knocked out of the 1948 playoffs when he developed an allergic reaction to penicillin administered for a sore throat. The following year it was even worse. “I broke my ankle in the finals,” he said. “Del Crandall (of the Danville Dodgers) was catching and we were talking (when I came to bat). He called for a changeup and I swung all the way around and hit my ankle with the head of the bat. And instead of a call-up to the Phillies, I went home.”

When asked how minor-league managers helped him develop as a pitcher and address his control problems, Stuffel responded resolutely, “There was hardly any coaching for the pitchers. Absolutely none. The managers never talked to me about pitching.” But then he offered an exception: George Earnshaw. The former A’s pitcher with 127 big-league wins was a scout for the Phillies in 1948 and on the big-league coaching staff in 1949 to 1951. Earnshaw, a hard thrower who battled his own control demons in his major-league career, viewed Stuffel as a kindred spirit. “Earnshaw would tell me, ‘Paul, you remind me of me when I was a young pitcher.’ One time (in 1948 with Terre Haute), Earnshaw was at a game and he told me to throw nothing but fastballs. He was in the stands and said he’d give me a sign to throw a curve,” said Stuffel. “He wanted me to concentrate.” Stuffel added that Earnshaw helped him to relax on the mound and instilled confidence. Though Earnshaw was known to have a short fuse with many pitching prospects and their work habits, Stuffel remembered him in spring training with the Phillies as an engaged teacher.

“I was a straight overhand thrower, but I could drop down to side-arm occasionally,” said Stuffel. “I had a curve, too, but we called it a ‘drop.’ I threw it overhand right off the tops of my fingers. My fastball was good and I threw it right down the chute and never pitched to the corners.” Despite the strain produced by an avalanche of walks, Stuffel remarkably never experienced any arm injuries and was accustomed working out of jams. With Terre Haute, he once issued 14 walks, described by sportswriter Bill Reddy as “awesome,” yet tossed a complete-game, six-hit victory.8

Promoted to the Triple-A Toronto Maple Leafs in 1950, Stuffel had a productive campaign for a talent-poor team that finished 30 games below .500. The second youngest hurler on the staff, he led the International League in strikeouts per nine innings (7.5), was the second hardest pitcher to hit, but also walked a league-worst 8.4 per nine innings. As the Phillies appeared to run away with the pennant in September, Stuffel was added to the club’s roster. He debuted on September 16 at Shibe Park in a game against the Cincinnati Reds and starter Ewell Blackwell (“Now that was a hard thrower that people were afraid of,” reminisced Stuffel). “(Manager Eddie) Sawyer told me to go to the mound to relieve Bob Miller,” said Stuffel about his first game. “I didn’t even have a chance to throw. I went to the mound and took my 11 warm-up tosses and shut ’em out for two innings.” In three appearances for the Whiz Kids, he gave up four hits and one run in five innings; he also walked one and struck out three. Though he was not on the Phillies’ roster for their four-game sweep by the New York Yankees in the World Series, Stuffel recalled fondly his experiences in the fall classic. He pitched batting practice in majestic Yankee Stadium, where he also shagged fly balls in the outfield; however, he watched all four games from the stands in civilian clothes.

The Phillies considered Stuffel, only 24 years old, among their top prospects during spring training in 1951. While Philadelphia sportswriter Stan Baumgartner thought he could develop into a 10-game winner, club owner Bob Carpenter compared him to 21-year-old southpaw, Curt Simmons, who had won 17 games for the pennant winners.9 Asked about the pressures of appearing annually at spring training from 1948 to 1953 trying to land a spot on the Phillies staff, Stuffel was direct in his answer. “The Phillies never really gave me a shot, and they didn’t trade me,” he said. “I was a pretty good prospect, but that’s all.” He also suggested that sometimes a player needed more than just talent to succeed. Once Krajnik and Earnshaw left the organization in 1950 and 1951 respectively, he thought he didn’t have an influential person who believed in him, and lacked a close relationship with the Phillies skipper. “Eddie Sawyer had managed in Utica where many of the Phillies had played, like Richie Ashburn, Granny Hamner, Stan Lopata. When he was with the Phillies, it was like his former team. I never had a chance to throw much, and I didn’t pitch on the side.” Major-league clubs typically carried just nine pitchers, and competition for the one or sometimes two open slots per season was fierce. “Pitchers didn’t help the newcomers,” said Stuffel. “Everyone was fighting for their own job.” Stuffel recalled an exception to that rule. He struck a close bond with his road roommate, Steve Ridzik, a 21-year-old right-hander who also debuted for the Phillies as a September call-up in 1950.

Stuffel was shipped to the Baltimore Orioles in the International League after the Phillies spring training in 1951. “I didn’t get to pitch much,” said Stuffel, who made just five appearances through the end of May. In his only complete game, he fanned 14 and walked 10 in a five-hit victory over the Springfield (Massachusetts) Cubs.10 “When you go out to the mound and pitch regularly, it’s easy,” he said. “But when you don’t pitch for several weeks and you’re thrown in there, well, it takes time to get used to it. You don’t have a rhythm. So the Phillies sent me to Schenectady so that I could pitch more.” Little did Stuffel know what “more” meant.

Just days before Stuffel reported to Schenectady, in eastern New York, he had married Marilyn Iden in Baltimore at Martin Luther Church. Marriage must have agreed with him. In his first appearance for the Schenectady Blue Jays, he hurled a no-hitter, striking out 20 and walking 10, and throwing two wild pitches to defeat the Elmira Pioneers, 6-3. In his first six days with the club, he tossed three complete games. In three months Stuffel logged 201 innings, won 15 of 25 decisions, and led the circuit in both strikeouts (183) and walks (138) while etching out a 3.31 ERA.

Stuffel made it back to the big leagues in September 1952 after winning 11 games and logging 182 innings with Baltimore. In the Phillies’ next to last game of the season, he made what turned out to be his first and only start in the big leagues. Facing the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds, Stuffel tossed four-hit ball over five innings, yielding three runs (two earned), and striking out one. “I tried to pitch everyone inside,” he said about issuing seven walks. He trailed 3-1 heading into the top of the fifth but the Phillies rallied for three two-out runs on an RBI single by Bill Nicholson and Del Ennis’s two-run home run to take the lead 4-3. Stuffel retired the Giants in the bottom of the fifth before being lifted for a pinch-hitter in the sixth. The Phillies then went on to win 7-3 to give him his first and only big-league win.

Stuffel made the Phillies staff as the club broke camp in 1953, in Steve O’Neill’s first full season as the team’s skipper. “It was a really rainy spring in April and May and many games were canceled,” Stuffel recalled. “I figured I’d get my chance with a lot of doubleheaders coming up, but that didn’t happen.” He made only two appearances in five weeks, walking all four batters he faced. (They eventually scored, giving Stuffel an unenviable ERA of “infinity.”)

In early June 1953 the Phillies sold Stuffel in a waiver transaction to the Memphis Chickasaws, the Chicago White Sox’ affiliate in the Double-A Southern Association. After throwing just 60 innings for Memphis in 1953, Stuffel was not invited to a big-league training camp for the first time in his pro career. But he revived his hopes for another shot by going 11-8 and logging 196 innings for the Chicks in 1954.

Over a three-year period, from 1954 to 1957, Stuffel pitched year-round. He said winter-league baseball gave him the chance to throw regularly, stay in shape, and earn a bit of money. He played in Puerto Rico with Mayaguez in 1954-55 and was named to the league’s all-star team the following season while helping lead skipper Ben Geraghty’s Caguas Creoles to the league title. In 1956-57 he pitched for Pastora in the Venezuelan League.

“We were on our way to Panama for the Caribbean World Series,” said Stuffel about an episode in his life that he regretted even 60 years later. “The team physician came back to me three times and said ‘Take these. They’ll help you relax.’ Finally, after he asked me a fourth time, I took them. They were two small blue or green pills. I was out of it after that. I couldn’t even throw and don’t remember anything.” Stuffel started the first game of the series, on February 10, 1956, and lost to Venezuela, 6-1. “I was naïve and always wondered what (the pills) were,” he said. “I didn’t smoke and didn’t drink much, and never took any more of those pills.” He mentioned that the scandals involving performance-enhancing drugs in baseball in the first decade of 2000 and beyond disgusted him.

Stuffel’s success with Caguas led to an invitation to the Chicago White Sox spring training in 1955. In Puerto Rico, he had worked on a new pitch, a slider. “Jim Konstanty (of the Phillies) taught me how to throw it,” said Stuffel. “It was straight overhand, and I had to keep the ball down below the batters’ waists or they’d hit it out of the park.” Though the pitch did not land him a job on a big-league staff, it helped keep him in Organized Baseball for a few more years as his heater lost a few ticks. Starting the season in Toronto, Stuffel was sent to Memphis in late May, and enjoyed a renaissance. He won 12 of 15 decisions, posted a career-low 2.60 ERA in 149 innings, and surrendered a league-low 6.3 hits per nine innings for the regular-season champions. Stuffel also suffered an injury that plagued him for most of the season. “I started a game against Nashville, but we had a curfew in Memphis, and had to play the last two innings the next day,” he said. “Well, I pitched and pulled a muscle right against my spine. I told the trainer about it and he told me not to worry. Back then you were like a horse. If you were injured, they’d just shoot you.”

After another trial with the White Sox in spring training in 1956, Stuffel was back in Memphis. “After my back injury, I couldn’t throw hard anymore,” he said of the excruciating pain. “That’s what ended my career.” He labored through a difficult campaign, going 4-10, with a 6.83 ERA in 108 innings, and drew his release from the Chicago. Not yet willing to give up on a dream, Stuffel played for four different minor-league teams (spring training with the Indianapolis Indians, and then with the Double-A Atlanta Crackers, Mobile Bears, and Austin Senators) in 1957 before hanging up his spikes. “My wife said to me ‘Paul, I want to go home,’ ” he explained. “We had bought a place in Canton and had a place to go to.”

Paul and his wife returned to their home town in Ohio, where they raised four children (three boys and a girl). After holding down a number of offseason jobs during his playing days, including working in the Union Metal factory and post office, Stuffel began a successful career as an insurance salesman for Nationwide. He eventually moved into management and took over a branch office in Alliance, Ohio, about 20 miles from Canton, and retired at the age of 65 in 1992. Marilyn died in June 2000, just months shy of their 50th wedding anniversary.

Stuffel may have lost his connection to major-league baseball over time, but never his passion for the sport. He coached in his children’s adolescent leagues, and tried to instill in them the love and respect for the game that his father gave him. “I’d play ball with my kids, and when they’d lose one, they’d go and get ball from my dresser. It had autographs from the Phillies players from who knows when,” he said with a laugh. “We’d play with it anyway.”

Stuffel resided in Alliance in his final years before his death on September 9, 2018. As he looked back over his career in baseball, he said he had no regrets. “I never paid much attention to statistics or records. I loved to play baseball and pitch.”

This biography appears in “The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant: The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2018), edited by C. Paul Rogers III and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted:

The Sporting News

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.com

SABR.org

Notes

1 The author expresses his gratitude to Paul Stuffel, whom he interviewed via telephone on September 15, 2014. Stuffel provided additional details in subsequent phone conversations in September and October, and read the biography to ensure its accuracy. All quotations from Stuffel are from these interviews unless otherwise noted.

2 “Wings Sign 3 Rookie Pitchers From Midwest,” Bradford (Pennsylvania) Era , March 22, 1946, 12.

3 Walter L. John, “Stuffel Has Plenty Stuff As Phil Strikeout Artist,” Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland), March 28, 1953, 14.

4 Associated Press, “Salina Shuts Out St. Joseph, 1-0,” Joplin (Missouri) Globe, August 22, 1947, 11.

5 Associated Press, “Terre Haute Ace Pitches Perfect Game in Three-I,” Muscatine (Iowa) Journal, August 28, 1948, 6.

6 Forrest Gardenwire, “Stuffel Pitches Four-Hitter and Plates Clincher,” Terre Haute (Indiana) Star, April 25, 1949, 12.

7 “Terre Haute Rallies in Fourteenth and Shades Davenport, 5-3. Terre Haute (Indiana) Star, July 21, 1949, 9.

8 Bill Reddy, “Visitors Grab Victory with 2-Run Fourth,” Post-Standard (Syracuse, New York), July 25, 1950, 14.

9 The Sporting News, January 10, 1951, 12 and February 21, 1951, 14.

10 Associated Press, “Stuffel Whiffs 14, Orioles Beat Springfield, 8-3,” Post-Standard (Syracuse, New York), May 19, 1951, 11.

Full Name

Paul Harrington Stuffel

Born

March 22, 1927 at Canton, OH (USA)

Died

September 9, 2018 at Canton, OH (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.