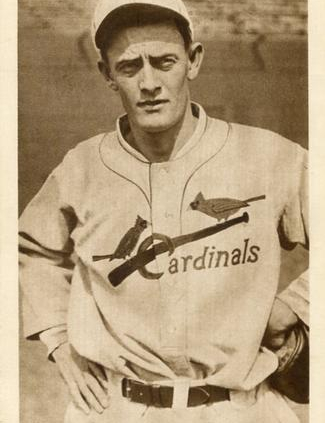

Tony Kaufmann

Over four seasons with a Chicago Cubs club that finished no better than fourth and was once dead last, Tony Kaufmann was a reliable starter and occasional reliever. During that stretch, 1923-1926, the righthander had a 52-41 record with a 3.68 ERA. But it was a turbulent 1927 season that shaped the rest of his professional baseball career.

Over four seasons with a Chicago Cubs club that finished no better than fourth and was once dead last, Tony Kaufmann was a reliable starter and occasional reliever. During that stretch, 1923-1926, the righthander had a 52-41 record with a 3.68 ERA. But it was a turbulent 1927 season that shaped the rest of his professional baseball career.

On June 7, 1927, the Cubs traded Kaufmann and shortstop Jimmy Cooney to the Philadelphia Phillies for pitcher Hal Carlson. Kaufmann had a 3-3 record in nine games for the Cubs, but his ERA was a troubling 6.41. Also he had clashed with manager Joe McCarthy, who once sent the hurler home to Chicago after a miserable outing on the road.

With the Phillies, Kaufmann complained of a sore arm – he had injured his elbow while bowling in the off-season – and pitched poorly: an 0-3 record with a 10.61 ERA in five starts. Frustrated with Kaufmann’s performance, Phillies owner William Baker suspended the hurler indefinitely and asked Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis to nullify the trade, claiming that the Cubs knew of Kaufmann’s sore arm when the deal was made. Landis refused, finding no indication that the Cubs were aware of the pitcher’s condition.

In September the St. Louis Cardinals acquired Kaufmann from the Phillies on waivers. After working out with the Redbirds, he reportedly was “in condition to go to the hill when needed.”1 But when he appeared in relief against the Giants in the second game of a doubleheader on September 14, he lasted only one-third of an inning, permitted an inherited runner to score, and allowed three runs on four hits. Kaufmann did not pitch again for the Cardinals in 1927, but with the exception of one season, he was affiliated with the St. Louis organization in one capacity or another – player, manager, coach, and scout – for the next 34 years.

Anthony John Charles Kaufmann was born in Chicago on December 16, 1900, to Peter Kaufmann, a carpenter, and Elizabeth (Rademacher) Kaufmann, a homemaker.2 Both were German immigrants from neighboring villages about 75 miles east of Düsseldorf. Peter arrived in the United States in 1882, Elizabeth two years later. They were married in Chicago on July 2, 1885, and had six children, of whom Tony was the youngest.

The family lived in the Ravenswood neighborhood on the city’s North Side. Tony’s parents died when he was a teenager, his mother in 1914 at age 52, his father two years later when he was 58. Thereafter the youngster lived with his sister Bertha and her husband, an inspector for an electrical company. Tony worked there as well.

As a boy, Kaufmann played ball around his neighborhood, eventually becoming a pitcher. When he was 16, the manager of the semipro Ravenswood Magnets asked him to meet the team in Evanston and throw to batters before a game. “I will if you give me my car fare,” Kaufmann replied. The manager agreed, and Kaufmann was sufficiently impressive to warrant a tryout in a game at Highland Park the following week. After striking out about 16 in that game while allowing only four or five hits, he had a job.3

In early 1920 Jack Sheehan, manager of the Winnipeg Maroons of the Class B Western Canada League, met with Kaufmann in Chicago and invited him to spring training in nearby Whitewater, Wisconsin, for a tryout. The 19-year-old righthander made the club, but the jump from semipro ball to Class B proved steep. Kaufmann’s 5-13 record and 3.90 earned-run average ranked near the bottom of the league, and he walked almost as many batters as he struck out. In a harbinger of things to come, he also played eight games in the outfield.

Back in Winnipeg for the 1921 season, Kaufmann won his first 10 starts en route to a 24-7 record. The Chicago Cubs purchased his contract on July 4, with the understanding that Kaufmann would not report until the following spring. However, the Cubs later had a change of heart and paid the Winnipeg club $1,000 to release him in September. Before departing for Chicago, Kaufmann pitched Winnipeg to a 4-1 win over Calgary in the opening game of Western Canada League playoffs.

On September 23 Kaufmann made his major-league debut at Cubs Park, later renamed Wrigley Field. He went the distance as the Cubs, mired in seventh place, routed the fourth-place Boston Braves, 13-5. A Chicago Tribune sportswriter called it “an impressive debut,” pointing out that Kaufmann held the Braves to two hits through the first five innings and pitched shutout ball after the visitors put up four runs in the sixth.4 At the plate he went 2-for-4, one of the hits a double off Braves starter Hugh McQuillan. Five days later Kaufmann picked up a save in his second appearance, going four innings against the Cincinnati Reds and allowing one run on two hits.

After those outings the Cubs viewed Kaufmann as a pitcher with a decent fastball and “highly deceptive” curve who needed “only a little instruction on the finer points.”5 At spring training in 1922, his curveball continued to impress. “He is one of the best young hook ball pitchers the Cubs have picked up in many years,” said the Chicago Tribune.6

As a reliever and part-time starter in 1922, the 5’11” 165-pound Kaufmann had a 7-13 record for the fifth-place Cubs with a 4.06 earned-run average in 153 innings across 37 games. One win came on August 25 at Cubs Park, when the home team outlasted the Philadelphia Phillies 26-23 in a slugfest featuring 51 hits, 21 walks, and nine errors. The 49 tallies remain the modern MLB record for the most runs in a game. Kaufmann started and went four innings, allowing six runs (three earned) on nine hits. He departed with an 11-6 lead, and the Cubs added 13 more runs in the bottom of the fourth. The Phillies, trailing 26-9 after seven innings, rallied for eight runs in the eighth and six more in the ninth before Tiny Osborne struck out Bevo LeBourveau with the bases loaded to preserve Kaufmann’s win.

Over the next four seasons Kaufmann pitched the best baseball of his major-league career: a 52-41 record, 3.68 ERA (110 Adjusted ERA+), and 1.373 WHIP in 780⅓ innings. He won 14 games in 1923 and 16 a year later, but his best season was 1926, when his record was 9-7. Kaufmann had a 2.7 WAR and compiled a 3.02 ERA and a 1.255 WHIP in 169⅔ innings. No less an authority than Branch Rickey considered him the most promising young pitcher in the major leagues.7 At the same time he was no slouch at the plate. He hit two homers in 1923 and two more in 1925. He had his best year at the plate in 1924, batting .316 (24-for-76), with five doubles and a homer for an above-average 103 OPS+.

In 1925 Kaufmann had what he later said was his biggest day in baseball.8 On July 4 he started for the Cubs against the visiting Cardinals in the second game of a doubleheader and took a no-hitter into the sixth inning. He settled for a three-hitter and a 9-1 win. The Cardinals got their three hits and sole run in the sixth after Kaufmann retired the first batter. He held them hitless the rest of the way and also hit two homers, driving in three runs. As a St. Louis sportswriter lamented, “Kaufmann alone accounted for enough runs to defeat the Cardinals.”9

The elbow injury suffered prior to the 1927 season robbed Kaufmann of his curveball, and a St. Louis sportswriter was not impressed when the Cardinals picked him up on waivers in September. “Just how Kaufmann, who has been of little service to the Cubs or Phils this year, can assist the Cards in their fight for the flag has a lot of ‘low visibility’ from our point of view,” wrote James Gould of the St. Louis Star.10 That assessment proved accurate, as Kaufmann recorded only one out in his sole appearance with the Cardinals.

In 1928 Kaufman went to spring training with an optimistic attitude and a new wife. On January 28 he married Frances Bewersdorf of Chicago, whom he had met five years earlier at Cubs Park. They honeymooned in Avon Park, Florida, where the Cardinals trained. He reported to camp on February 24, anxious to show manager Bill McKechnie what he could do. After seeing “every doctor and bonesetter in the country,” the pitcher said, there was “no pain at all” in his elbow.11

Kaufmann started the season with the Cardinals but had mixed results. After two relief appearances in which he pitched four scoreless innings, he allowed three runs without recording an out in his only start. He also was ineffective in another relief stint three weeks later, giving up two runs on four hits, one a home run, in two-thirds of an inning. When the Cardinals optioned him to Rochester (New York) of the International League on June 12, his record stood at 0-0 with 9.46 ERA.

At Rochester, Kaufmann was inconsistent and finished the season with a middling 3-2 record and a 4.40 ERA. He fared considerably better as a hitter. When the Red Wings suffered a rash of injuries at the end of July, manager Billy Southworth moved Kaufmann to the outfield. He appeared in 29 games as an outfielder, batted .402 overall with 30 RBIs, and helped Rochester win its first pennant since 1911.

On October 3 the New York Giants claimed Kaufmann in the Rule 5 draft on the strength of his hitting at Rochester. Sam Breadon, owner of the Cardinals, believed that other clubs would pass on Kaufmann, thinking that he was a broken-down pitcher trying to stay in the game by playing in the outfield. But the Giants had scouts looking at Kaufmann, and their favorable reports convinced manager John McGraw to draft him. Upon hearing of the Giants’ move, Breadon tried to buy Kaufmann from the Giants, but McGraw declined.

McGraw liked what he saw of Kaufmann at spring training in 1929, and when the season began he platooned the new outfielder and the left-handed Mel Ott in right field. This arrangement ended quickly when Kaufmann failed to hit. His futility “may have convinced McGraw that Ott certainly could do no worse [against left-handers] and might possibly do better.”12 Kaufmann managed to drive in a run with a sacrifice fly on May 20 against Brooklyn but did not get a base hit until August 1, when he singled off Dolf Luque at Cincinnati. Used primarily as a defensive replacement and pinch-runner, he finished the season with one hit, one RBI, and a .031 batting average in 40 plate appearances over 39 games.

After the season the Giants unsurprisingly parted ways with Kaufmann. The Cardinals picked him up on waivers in mid-December and the following month optioned him to the Houston Buffaloes, the organization’s Texas League farm team. In making the announcement, Buffs president Fred Ankenman said Kaufmann would primarily be an outfielder but would be given a chance on the mound if his arm was strong enough.13

Kaufmann opened the 1930 season in right field for the Buffs. The sports editor of the Houston Post-Dispatch described him as “a speedy, graceful, effective fielder” and opined that he was “the most dangerous hitter on the Houston club, and certainly one of the most dangerous in the league.”14 When the first half of the split season ended, he had played 73 games in right field and batted .312 with 64 RBIs.15 In the season’s second half, Kaufmann primarily pitched. He posted a 7-2 record in 80 innings for the Buffs and led the league in ERA (2.36) and WHIP (1.100).16 He also was one of six pitchers on the Texas League all-star team chosen for The Sporting News, joining Houston teammate Dizzy Dean.17

The parent Cardinals, who were in the thick of the pennant race, recalled Kaufmann at the end of August. He made two appearances. On September 14, he relieved in a 7-4 loss at Boston but did not figure in the decision. In 3⅓ innings he allowed one run on four hits and reportedly had “plenty of ‘stuff’ on the ball.”18 However, the Pirates hit him hard on September 27, the day after the Cardinals clinched the pennant. Kaufmann started and went seven innings, allowed eight runs on 11 hits, and took the loss. He was not on the St. Louis roster for the World Series, which the Cardinals lost to Connie Mack’s powerful Philadelphia Athletics.

At spring training in 1931, the Cardinals had a crowd of pitchers in camp, but Kaufmann made a strong showing and got a spot on the Opening Day roster. He remained with the club all season, pitching almost exclusively in relief and finishing with a 1-1 record and a 6.06 ERA in 15 games.

His win came against Brooklyn in relief of Bill Hallahan at Sportsman’s Park on September 21, five days after the Cardinals clinched the pennant. He entered the game with one out in the top of the sixth with St. Louis trailing 10-7 and pitched perfect ball for the next 4⅔ innings, striking out five. The Cardinals rallied to tie the game in the eighth and won it in the tenth when Ripper Collins tripled to drive in Jim Bottomley from first base.

Kaufmann was among the 25 Cardinals on the roster for the World Series, which St. Louis won in a rematch against the Athletics. He did not play but received a full winner’s share, $4,484.25. As manager Gabby Street explained, winning the National League pennant and the World Series title was a group effort to which “each member of the troupe contributed.” Kaufmann “won only one game for us all season [but] kept the boys on edge by serving as the pitcher during the preliminary batting practice each afternoon.”19

In 1932 Kaufmann was back in the minors. He was with the Cardinals for the first two weeks of the season but made no appearances before being sent to Rochester. Except for a brief stint with the Cardinals in 1935 – 0-0 in three games, all in relief, with a 2.45 ERA – he remained at Rochester for six seasons. In that stretch with the Red Wings, Kaufmann compiled a 48-58 record in 886 innings over 161 games with a 4.36 ERA. He hit .266 and in two seasons spent time in the outfield. The Red Wings honored him with a special night in 1937 to recognize him for long and faithful service to the club. When he departed in 1938 to manage the Cardinals’ Class B team in Decatur, Illinois, the Rochester Democrat-Chronicle called him “one of Rochester’s best loved ball players.”20

Kaufmann managed the Decatur team from 1938 through late June of 1940, when he returned to Rochester to direct the Red Wings. Decatur won the Shaughnessy playoffs to take the Three-I League pennant in 1938 and advanced to the final round in 1939 before losing to Springfield. When Kaufmann left to take the Rochester job, L.J. Wylie, president of the Decatur club, praised him and the Cardinals’ decision to promote him. “I sure hate to see Tony go,” Wylie said. “He has been 100 per cent honest, one of the finest men I have ever worked with in baseball and a credit to the game and Decatur. We’ll miss him but I’m happy over the promotion he deserves.”21

The 1940 Red Wings had three managers before Kaufmann. Billy Southworth began the season but departed in June to manage the Cardinals when Ray Blades was fired. Southworth’s replacement, Estel Crabtree, was at the helm only two weeks before being hospitalized with a kidney ailment. And prior to Kaufmann’s arrival to take over from Crabtree, pitcher Mike Ryba served as interim manager. The Red Wings were in first place when Southworth left, and that is where they finished. The players voted full $4,000 shares of the first-place money to both Kaufmann and Crabtree.

In 1941 Kaufmann was back to manage the Red Wings, who finished fourth with an 84-68 record and lost to Newark in the first round of the playoffs. Despite the disappointing season, Kaufmann had memorable encounters with Babe Ruth and Stan Musial. On August 14 Ruth took part in the Red Wings’ annual charity event before a game against the visiting Montreal Royals. Kaufmann threw batting practice pitches to the 46-year-old Babe, who had not swung a bat in two years. After two dozen futile swings, he slammed a line drive over the right-field fence, “thoroughly delighting the howling fans, who gave him a tremendous ovation.”22

Musial began the season at Springfield, Missouri, in the Class C Western Association and was promoted to double-A Rochester after batting .379 in 87 games. On August 2, when the Red Wings were fighting for a playoff berth, he went 4-for-7 against the Newark Bears, the Yankees’ top farm club, in an extra-inning game that Rochester won, 6-4. In the top of the 11th, with the score tied at 4-4 and Carden Gillenwater at first base, Kaufmann instructed Musial to fake a bunt, swing away, and try to push the ball past Bears third baseman Hank Majeski. Anticipating a sacrifice, Majeski began moving onto the infield grass when he heard the raspy-voiced Kaufmann, coaching at third, yelling at him: “Be careful, don’t get too close, this kid will kill you.” Majeski thought Kaufmann was kidding, but Musial hit away and lined a double into left field, sending Gillenwater to third. “I swear the ball took the button off my cap,” Majeski said. “It went by so fast I didn’t get a chance to move a leg or arm.”23 Gillenwater, however, was stranded at third.

The same situation arose two innings later. With Gillenwater at first base, Majeski disregarded another warning from Kaufmann – “don’t be a dope, get back” – and crept closer toward the plate. Musial, after again faking a bunt, doubled to left. “I didn’t see the ball,” Majeski said. “I was frozen.”24 Gillenwater went to third and scored the decisive run when Newark pitcher Al Gettel balked. After the game, Kaufmann asked Musial whether he had previously executed the fake-bunt maneuver. “Naw,” said the 20-year-old Musial, “but it’s easy.”25 And in his long career, he did not recall doing it again.26

Musial batted .326 in 54 games while another outfielder, Erv Dusak, hit 304 in 51 games. Kaufmann recommended that the Cardinals promote both men when rosters expanded in September. Because of Musial’s unique batting stance, Kaufmann told the Cardinals that Dusak was better equipped to succeed in the majors. “I certainly blew one there,” Kaufmann said years later.27 Dusak hit .240 in three full seasons and parts of five others with the Cardinals. Musial, with a .331 lifetime batting average, 3,630 hits, and 475 home runs, is in the Hall of Fame.

Near the end of spring training in 1942, Rickey visited the Red Wings’ camp to look over the players. Upon leaving, he shook Kaufmann’s hand and said solemnly, “Lots of luck, fellow, you’re going to need it for a while.”28 That luck did not materialize. With Rochester in the cellar, the Cardinals dismissed Kaufmann on May 25 and reassigned him as a scout for the major-league club. That assignment did not last long; on June 3 he was named manager at Decatur, returning to the club he had first piloted. Decatur finished last, as did Rochester.

The disheartening season marked the end of Kaufmann’s managerial career. For the next four years, 1943-1946, he scouted for the Cardinals, covering the Midwest from his Chicago home. One day the club dispatched him to Peoria to look at a reportedly hot prospect. The player “looked all right” as a hitter and was “passable” as a fielder, Kaufmann said later, but his speed was an issue. When the player batted again, Kaufmann – who had left home without his stopwatch – went behind the crowd assembled along the first-base line and positioned himself even with home plate. “When this big kid hit the ball, I took off and ran as hard as I could down a line parallel to first base,” Kaufmann said. “When I got even with the bag, I looked over at the diamond [and] had beat the kid by a couple of strides.” His assessment of the player was not favorable. “If this kid couldn’t outrun me when I was past 40 and wearing street shoes,” he said, “then he wasn’t a major league prospect.”29

In 1946 Kaufmann received additional assignments from new Cardinals manager Eddie Dyer. Dyer first tabbed him to assist at the club’s spring training camp in St. Petersburg. Several months later, in anticipation of a matchup with Boston in the World Series, Dyer dispatched Kaufmann and fellow scout Ken Penner to see how American League clubs shifted defensively against Ted Williams and pitched to him. “Cleveland’s [shift], we felt, was too extreme to be effective,” Kaufmann said. “We settled on the Detroit shift as the best.” The scouts also recommended that Williams “be pitched inside, and that’s what he got throughout the Series.”30 St. Louis prevailed in seven games, and Williams hit .200 (5-for-25) with no extra-base hits and one RBI.

The following season, Kaufmann joined Dyer’s staff as a major-league coach. He usually directed traffic from the third-base coaching box and, as Dyer once said, was the club’s “good humor man” who kept the players loose with his jokes.31 After three consecutive second-place finishes, the Cardinals fell to fifth in 1950, barely surpassing the .500 mark. Manager Dyer was forced out, replaced by shortstop Marty Marion, and Kaufmann returned to scouting. Again working the midwest region, he scouted for the Cardinals through the 1961 season.32

During his playing days Kaufmann operated a Chicago cigar store in the offseason, but little else is known about his life outside baseball. He and his wife Frances, who on occasion accompanied him on scouting trips, had no children. She passed away in Chicago on May 15, 1978, at age 72. Tony was 81 when he died on June 4, 1982, in a hospital in Elgin, Illinois, a Chicago suburb. He is buried alongside his wife in Mount Emblem Cemetery at Elmhurst, Illinois.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo. The author also would like to thank Cassidy Lent, manager of reference services at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum Giamatti Research Center, for her assistance.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author consulted the SABR Bio-Project, https://sabr.org/bioproject, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, newspapers available at Newspapers.com and GenealogyBank.com; Tony Kaufmann’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and his player contract card maintained by The Sporting News, available at https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll3/id/123193/rec/1.

Notes

1 “Tony Kaufmann is Eligible to Hurl for Cardinals,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 13, 1927: 17.

2 While sources are in agreement as to his birthdate, determining his full name is not a straightforward task. There apparently is no birth certificate, which was not uncommon in Chicago at the time, but records for St. Matthias Parish show that he was born December 16, 1900, and christened Joannes Antonius, i.e., John Anthony, on January 6, 1901. Chicago Catholic Church Records, 1833-1925, available at FamilySearch.org. In the 1910 US Census, the first in which he appears, his name is listed as “Anthony J.” When he registered for the draft in World War II, he gave his name as “Tony John Charles Kaufmann.” World War II Draft Registration Card (February 16, 1942), available at Ancestry.com. He is listed as Tony J. Kaufmann in the Social Security Application and Claims Index available at Ancestry.com. Standard baseball references list him as both “Anthony John” and “Anthony Charles.” E.g., 1950 Baseball Register (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1950), 264 (John); The Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Macmillan Co., 1969), 1050, 1928 (Charles).

3 “Tony Kaufmann Now Promising Twirler,” Chicago Eagle, September 9, 1922: 2.

4 I.E. Sanborn, “Cubs Rookies Show Some Class by Walloping the Braves, 13-5,” Chicago Tribune, September 24, 1921: 8.

5 “Home Talent,” Chicago Tribune, December 14, 1921: 20.

6 “Cubs in Hard Workout,” Chicago Tribune, March 22, 1922: 19.

7 Lloyd Gregory, “Buffs Hustle to 4-1 Win Over Sports,” Houston Post-Dispatch, July 29, 1930: 12.

8 Tony Kaufmann and Hal Totten, “My Biggest Baseball Day,” Chicago Daily News, January 29, 1944: 17.

9 J. Roy Stockton, “Pitchers Fail and Cards Drop Two Games, 7-6 and 9-1,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 5, 1925: 2S.

10 James M. Gould, “Gould’s Gossip,” St. Louis Star, September 8, 1927: Sports, 2.

11 Ray J. Gillespie, “Hurler Kaufmann Declares He Will Stage ‘Comeback,’” St. Louis Star, February 25, 1928: 11.

12 Frank Wallace, “Ott, Once Yanked Against Southpaws, Belting Them Now Like Old Cousins,” New York Daily News, May 19, 1929: 31.

13 “Houston Club Gets Tony Kaufmann,” Houston Post-Dispatch, January 26, 1930: Sports, 1.

14 Lloyd Gregory, “Looking ‘em Over,” Houston Post-Dispatch, April 19, 1930: State News, 4.

15 “Joel Hunt Leads Houston Hitters,” Houston Post, July 1930: Sports, 2.

16 Gus Ketchum of Shreveport had a 2.25 ERA but pitched only 16 innings.

17 “Five Fort Worth Men on All-Star Team,” The Sporting News, October 2, 1930: 6.

18 Walter (Red) Smith, “Cardinals Expect Pennant to be Decided in Two Series This Week,” St. Louis Star, September 15, 1930: 16.

19 Sid Keener’s Column,” St. Louis Star, October 29, 1931: 19.

20 Don Hassett, “Tony Kaufmann Leaves Wings to Manage Decatur Club in Three-I League,” Rochester Democrat-Chronicle, January 23, 1938: 5C.

21 George Kreker, “Kaufmann Named Manager at Rochester; Commies Win, 4-1,” Decatur Herald, June 27, 1940: 11.

22 “Yankees Are a Shoo-in, Ruth Says on Visit Here,” Rochester Democrat-Chronicle, August 15, 1941: 26.

23 Willie Klein, “On Second Thought,” Newark Star-Ledger, April 26, 1964: S-3.

24 Klein, “On Second Thought.”

25 Elliot Cushing, “Sports Eye View,” Rochester Democrat-Chronicle, September 23, 1941: 20.

26 Stan Musial with Bob Broeg, Stan Musial: The Man’s Own Story (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1964), 44.

27 Paul Pinckney, “In the Pink,” Rochester Democrat-Chronicle, May 20, 1955: 38.

28 Elliott Cushing, “Sports Eye View,” Rochester Democrat-Chronicle, April 13, 1942: 16.

29 Clark Nealon, “Post Time,” Houston Post, April 15, 1954: sec. 4, 1.

30 Milt Woodard, “Two-Man Spy System Helped Cards to Title,” The Sporting News, October 23, 1946: 12.

31 Red Smith, “Sport Cameo,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 18, 1950: 5D.

32 “Obituaries – Anthony C. (Tony) Kaufmann,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1982: 51. He filed for Social Security benefits in December 1962, just after he turned 62. Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007, available at Ancestry.com.

Full Name

Anthony Charles Kaufmann

Born

December 16, 1900 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

June 4, 1982 at Elgin, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.