Milo Candini

Right-hander Milo Candini debuted for the Washington Senators in 1943, after toiling in the New York Yankees farm system for six years. Once hailed as the “sensation of the American League,” Candini won his first seven decisions, including five consecutive starts.1 But he was plagued by arm miseries throughout his 20-year professional career, and his quick start proved to be an aberration. He finished with a 26-21 record in eight big-league seasons, the final two (1950-1951) with the Philadelphia Phillies.

Right-hander Milo Candini debuted for the Washington Senators in 1943, after toiling in the New York Yankees farm system for six years. Once hailed as the “sensation of the American League,” Candini won his first seven decisions, including five consecutive starts.1 But he was plagued by arm miseries throughout his 20-year professional career, and his quick start proved to be an aberration. He finished with a 26-21 record in eight big-league seasons, the final two (1950-1951) with the Philadelphia Phillies.

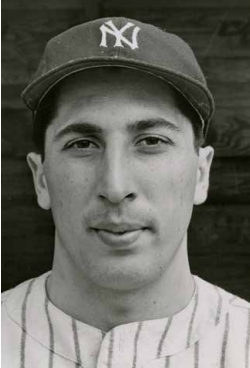

Candini was born Mario Gustino Candini on August 3, 1917, in Manteca, California, 75 miles east of San Francisco. His parents, Caesar and Lucy Candini, were Italian immigrants who arrived in the United States at the turn of the 20th century and settled in Athol, a bustling industrial center and rail hub in north-central Massachusetts. They eventually migrated to the Central Valley in Northern California, where they both found jobs as canners in the burgeoning agriculture business of the area. Mario was the seventh of eight children. Given the heightened ethnic tension spawned by World War I and the desire to assimilate more quickly into American society, Mario became Milo. However, his Southern European heritage always stayed with him. Throughout his baseball career, sportswriters often referred to him an “Italian” or the “Italian boy,” or joked about his surname, comparing Candini to Houdini.2 Candini the “mound magician” was a common moniker.3 In addition to his Italian background, sportswriters often made reference to Candini’s good looks. “[He] looks like a Latin movie star,” reported the Associated Press.4 He was an even 6-feet tall and weighed about 185 pounds, with chiseled facial features, black hair, and dark eyes which gave rise to portrayals that he was a ladies’ man.

Candini was an exceptional athlete at Manteca High School, where he lettered in baseball, basketball, football, and track all four years. He was named the medium school state athlete of the year in 1934 and 1935, and baseball player of the year in 1935 and 1936 while leading the Buffaloes to consecutive West Side league titles.5 In his senior year, the hard-throwing prep phenom tossed a no-hitter, and once struck out 45 batters over two games.6 Candini played American Legion ball in the summer and in the competitive fall semipro leagues in the greater Oakland area, located about 50 miles away. His mound exploits caught the attention of a number of teams in the Pacific Coast League, as well as scout Joe Devine, who scoured the region for the Yankees and had signed another son of Italian immigrants, Joe DiMaggio, a year earlier. Upon graduating from high school in 1936, Candini signed with Devine and the Yankees.

In 1937 Candini began his professional baseball career with the El Paso Texans in the newly re-established, four-team Class-D Arizona-Texas League. Candini led the league with 21 wins against only 7 losses and finished second in innings (251) for the regular-season champions. He struck out 165 (second to teammate Floyd Bevens’ 179), but also walked a league-high 141, contributing to his high ERA (4.23). In a remarkable complete game against the Albuquerque Cardinals, Candini surrendered 10 hits and walked 17 batters, but won the game, 14-13.7 Baseball was not the teenager’s only concern. He had married his high-school sweetheart, Bernice, the previous year. Their second child, Jarrett, was born during the regular season, joining daughter Chareen.

Candini spent his offseason working in oil fields and playing semipro baseball in the arid climate of West Texas, before returning to Northern California to participate in the Yankees rookie camp at Roosevelt Field in Modesto. New York’s farm system trailed only the St Louis Cardinals’ in its breadth. With 12 affiliates in 1938 and 16 in 1939, the Yankees’ “chain gang” was flush with hurlers, well in excess of 100 each year. Candini spent those two seasons in Class B, posting sturdy yet unspectacular records of 12-13 (3.49 ERA in 173 innings) with the Norfolk (Virginia) Tars of the Piedmont League and 13-8 (4.17 ERA in 205 innings) for the Wenatchee (Washington) Chiefs of the Western International League.

The Yankees promoted Candini to the Oakland Oaks of the PCL, a step below the big leagues, in 1940. After walking 33 batters in 42⅔ innings, he was reassigned to Wenatchee, where despite arm pain he won 13 games for the league’s worst team which finished 30 games below .500. The Kansas City Star reported that Candini had pitched with a chronically sore arm since the “punishment he received” with El Paso in 1937.8

Little was expected of Candini when he reported to spring training with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association in 1941. Pain-free for the first time in four years, Candini impressed skipper Billy Meyer with a productive camp, including limiting the Washington Senators to just one hit over five innings in an exhibition game. The Yankees rebuffed Senators owner Clark Griffith’s overtures to buy the 23-year-old hurler, now described as a serious big-league prospect.9 Praised for his “deceptive delivery” and heater, Candini was an effective swingman for the Blues, starting 15 of 35 games and etching out a team-best 3.26 ERA in 141 innings. Two exceptional outings in exhibition games against big-league clubs during the season guaranteed his promotion to the Yankees. In August he tossed a two-hitter against the Cincinnati Reds and subsequently held the Bronx Bombers to just one hit in six innings on August 26. The New York Sunraved that Candini was “plenty fast” but cautioned that he “needs a better curve” to succeed in the majors.10 The Yankees added him to their 40-man roster in September.11

At his first big-league spring training with the reigning World Series champion Yankees, in 1942, Candini battled prospects Johnny Lindell, Hank Borowy, Mel Queen, Al Gettel, and Rugger Ardizoia for the two open spots on the staff vacated by relievers Steve Peek and Charley Stanceu, who were in the military. Plagued by control problems, Candini was optioned to the Newark Bears of the International League. His arm pain soon resurfaced, rendering him ineffective for most of the season. With a 4-7 record and a team-high 5.21 ERA in 95 innings, his days in the Yankees’ system were numbered.

Long coveted by Washington, Candini was a throw-in when the Senators sent swingman Bill Zuber to the Yankees for infielder Jerry Priddy on January 29, 1943. When Candini arrived at spring training, conducted nine miles northeast of Washington in College Park, Maryland, due to wartime travel restrictions, team trainer Mike Martin was charged with getting his arm back in shape. Coincidentally, the pitcher had injured his arm the previous season in an exhibition game against Washington.12 Candini, lacking a fastball and reluctant to throw a curve, was castigated as a “dismal flop,” but still landed a spot on the staff, the league’s worst in 1942 with a 4.58 ERA.13

Relegated to the far end of the bullpen, Candini made his major-league debut on May 1, setting down the only two batters he faced in a loss to the Yankees. He picked up victories in his next two relief appearances and earned his first start on June 2. Playing under the lights at Griffith Stadium, Candini tossed an eight-hit complete game to defeat the Cleveland Indians, 13-1. He also went 2-for-5 at the plate, scored a run, and knocked in one. With the country at war, Candini became an early-season feel-good story and emerged as the hottest pitcher in baseball. In a stretch of three starts in June, he shut out the Boston Red Sox on three hits at Fenway Park, hurled a career-best 11-inning complete game to defeat the Philadelphia Athletics at Shibe Park, and then capped it off by slugging his first and only major-league home run and blanking New York, 6-0, at Yankee Stadium.

One of the surprise teams of baseball, the Senators improved by a major-league-best 22 games to finish in second place, 84-69, their best record since their last pennant in 1933. They were led by a strong pitching staff, including 23-year-old Early Wynn (18-12) and knuckleballer Dutch Leonard. After Candini’s exceptional start (7-0 and 0.94 ERA in his first 76⅓ innings), he cooled off, but still finished tied for second on the staff with 11 victories. His 2.49 ERA in 166 innings trailed only knuckleballer Mickey Haefner’s 2.29, and was good for sixth in the league. The Sporting News named Candini, Charley Wensloff of the Yankees, and the Philadelphia Phillies’ Al Gerheauser to the All-Rookie team. Candini took advantage of his new-found notoriety to participate in a barnstorming tour organized by Charles DeWitt of the St. Louis Browns in October.

For seemingly the first time since Walter Johnson’s retirement in 1927, the Senators didn’t need pitching as the 1944 season commenced. A quartet of hurlers (Haefner, Leonard, Wynn, and 40-year-old Johnny Niggeling) each logged at least 200 innings, and pushed Candini to the bullpen. After seeing mainly mop-up duty through mid-June, Candini made six consecutive effective starts, tossing four complete-game victories (including his final two of five career shutouts), yielding just 14 runs in 50⅓ innings (2.49 ERA). But that stretch proved to be his final effective stint as a starter in the big leagues. He was knocked out in the second inning in his next two starts and lost his place in the rotation. Given a spot start on August 6 against Boston, Candini broke his finger in a bunt attempt when he was struck in the hand by a pitch from Pinky Woods.14 Ineffective in his return six weeks later, Candini concluded the season with a 6-7 record and 4.11 ERA in 103 innings. He also helped himself at the plate, batting .313 (10-for-32); for his career he hit a respectable .243 (35-for-144).

Candini’s baseball career was interrupted when he was inducted into the Army in March 1945. He was stationed at Camp Beale in Northern California, and pitched for the base team. Subsequently deployed to the Pacific Theater and stationed in Japan and Korea, Candini pitched for the 24th Corps baseball team in tournaments in Japan and the Philippines. After his discharge in early August 1946, he made an exciting return to the Senators by tossing four scoreless innings of relief to earn the victory in an extra-inning game against the Browns on August 25, in his first big-league game in almost two years.

Candini appeared almost exclusively in mop-up situations for the seventh-place Senators in 1947 and 1948, logging about 90 innings each season and posting an ERA north of 5.00. His highlight during those years may have come on a day that he did not pitch. On August 10, 1947, he and five other players were presented with World War II victory medals by Rear Admiral John E. Wood and Brigadier General Wayne C. Zimmer between games of a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Athletics.15

Candini had a special assignment for Washington’s season opener on April 19, 1949. He served as President Harry Truman’s escort (or “body guard” as the media exaggerated at the time);16however, it is unclear how well the right-hander could protect the nation’s first fan since he was for some reason wearing a left-handed first baseman’s glove. Suffering from a wrenched knee and a pulled back muscle, Candini drew his release from the Senators in May, and was sold outright to the Oakland Oaks. Unexpectedly, the 31-year-old revived his career playing in the temperate climate, tying for the team lead with 15 victories in the 187-game season. After the season, Candini joined the San Francisco Seals for their barnstorming tour of Japan.

On November 17, 1949, the Philadelphia Phillies selected Candini in the Rule 5 draft. His selection and acquisition price of $10,000 helped fuel the discussion about the future of the PCL as a minor league and its possible elevation to a third major league. A controversy of sorts began when Bob Carpenter, the team’s owner and an heir to the DuPont fortune, commented crassly, “In these days of high finance, high taxes, and high prices, we are lucky to draw a breath for $10,000. At least [Candini] has a pair of spiked shoes and a toe plate. I’d be willing to pay $25,000 for a good windup.”17 Oaks majority owner Brick Laws was livid with Major League Baseball and the draft (they also lost Billy Martin and Jackie Jensen to the majors after the 1949 season). “If the Phils are a major-league outfit, why is it necessary for them to draft a player from our roster?” he asked.18 Three years later, in 1952, the PCL was given an “open” classification, thereby limiting the right of major-league teams to draft its players.

The Phillies had high expectations when Candini reported to spring training in Clearwater, in 1950. The previous season they had posting a winning record for just the second time since 1917, and were led by a strong young pitching staff. Skipper Eddie Sawyer counted on six hurlers as primary starters and occasional relievers (Robin Roberts, Curt Simmons, Russ Meyer, Bob Miller, and Bubba Church, all 26 years old or younger, and veteran Ken Heintzelman). Jim Konstanty, a 33-year-old reliever in just his second full season in the big leagues, emerged as the talk of baseball, pitching in a then-record 74 games, and winning the MVP award. “Milo had been a very good pitcher and he could still pitch,” said Sawyer. “It was really my fault the way the year developed and with Konstanty, there just weren’t that many spots I could use him.”19

Candini, in his accustomed role as a mop-up artist, hurled in just 18 games (16 of which were losses by the Phillies), and posted a respectable 2.70 ERA in 30 innings. He and his roommate, second baseman Jimmy Bloodworth, were primarily spectators as the Whiz Kids captured Philadelphia’s first pennant since 1915. Candini did not see action in Philadelphia’s four-game sweep at the hands of the New York Yankees in the World Series.

Candini’s only win of the 1950 season (he had no losses) came on July 26 against the Chicago Cubs in relief of Russ Meyer, who had been tossed after protesting a balk call in the fifth inning while trailing 4-0. The Phillies then scored six runs in the bottom of the sixth to make Candini, who pitched 1⅔ scoreless innings, the winning pitcher.20

The Phillies eventually won the pennant on the final day of the season in a dramatic 10-inning victory over the Brooklyn Dodgers. After the season, when Candini was trying to negotiate a raise, he referenced his one win and told Phillies owner Bob Carpenter, “We couldn’t have won the pennant without me.”21

Candini’s big-league career came to a close in 1951 after he logged just 30 mostly ineffective innings (6.00 ERA) with the Phillies. In parts of eight seasons, the right-hander appeared in 174 games, posted a 3.92 ERA in 537⅔ innings, and won 26 games while losing 21. In the offseason he was sold to the PCL’s Los Angeles Angels, an affiliate of the Chicago Cubs.

Candini’s elbow pain, often described as bone chips, resurfaced in spring training with the Angels. Counted on as a starter for the Angels, Candini was sold during at the end of camp to Oakland, his third stint with the club. Limited by arm pain, he transformed himself into one of the PCL’s best and most effective relievers over the next six years. He set a league record by pitching in 69 games for the Oaks in 1952 (he also etched out a robust 2.57 ERA in 133 innings). Traded to the Sacramento Solons the following season, Candini emerged as a fan favorite, once named the most popular player on the team.22 In his 20th and final season in Organized Baseball, the 39-year-old pitched in 57 games, logged 100 innings and posted a 1.98 ERA. Despite that success, Candini decided to retire. In 12 seasons in the minors, he appeared in 495 games, won 124 and lost 90 with a 3.80 ERA in 1,626⅔ innings.

Candini settled down with his second wife, Viola, in the San Joaquin Central Valley. He worked for Contadina Foods, and later operated Milo’s Liquors in Manteca from 1962 to 1979 before retiring. He played in local softball leagues well into his early 50s and according to the local paper, the Manteca Bulletin, was an ardent supporter of baseball in the town.23 Manteca’s sandlots, Big League Dreams, are located on Milo Candini Drive.

Candini died from prostate cancer at the age of 80 on March 17, 1998. He was buried in Park View Cemetery in Manteca. In 1994 he was inducted into the Manteca Hall of Fame, and in 2012 into the Sac-Joaquin (Sacramento-San Joaquin) Section High School Sports Hall of Fame.24

This biography appears in “The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant: The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2018), edited by C. Paul Rogers III and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted the following:

The Sporting News

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.com

SABR.org

Notes

1 The quotation comes from Lee Dunbar, “Candini Makes Pitching History,” Oakland (California) Times, July 1, 1943, 21.

2 El Paso (Texas) Herald-Tribune, April 9, 1937, 17.

3 Harry Grayson, NEA, “Washington Makes A Great Deal For Zuber; Jerry Priddy All Over The Senator Infield; Magician Milo Candini Dealing Like A Shark,” Mount Carmel (Pennsylvania) Item, June 26, 1943, 6.

4 AP, “Senior Loop Nine Beats Americans,” Post Register (Idaho Falls, Idaho), October 6, 1944, 10.

5 Sacramento Bee, June 8, 2012.

6 Omer V. Crane, “Modesto and Manteca Will Compete For Title Today,” Modesto Bee, May 8, 1936, 24.

7 AP, “3000 Albuquerque Fans See Milo Walk 17, Texans Win,” El Paso Herald-Post, July 17, 1937, 9.

8 “Milo Candini Is Another of Meyer’s Big Pitching Hopes,” Kansas City Star, April 16, 1941, 14.

9 Ibid.

10 “Kansas City Hurler Turns Back Yanks With Only One Run,” New York Sun, August 27, 1941, 30.

11 The Sporting News, September 18, 1941, 8.

12 The Sporting News, March 25, 1943, 3.

13 The Spotting News, April 15, 1943, 76.

14 AP, “Candini Injured,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening Journal, August 7, 1944, 8.

15 The Sporting News, August 20, 1947, 19.

16 Harmon W. Nichols, UP, “Nation’s No. 1 Baseball Fan Boos Umpire, Protector Says,” Bakersfield Californian, April 20, 1949, 25.

17 The Sporting News, December 7, 1949, 12.

18 Dennis Snelling, The Greatest Minor League: A History of the Pacific Coast League, 1903-1957 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011), 234.

19 Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 238.

20 Edward Burns, “Frisch Rakes Cubs; Lose in 6-Walk Inning,” Chicago Tribune, July 22, 1950, B1.

21 Roberts and Rogers, 237.

22 The Sporting News, September 25, 1957, 40.

23 Dennis Wyatt, Milo Candini: A baseball player for all time,” Manteca Bulletin, October 9, 2011, mantecabulletin.com/archives/28182/.

24 Jonamar Jacinto, “SJS Selects MHS grads for Hall of Fame,” Manteca Bulletin, June 9, 2012, mantecabulletin.com/archives/44993/.

Full Name

Milo Cain Candini

Born

August 3, 1917 at Manteca, CA (USA)

Died

March 17, 1998 at Manteca, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.