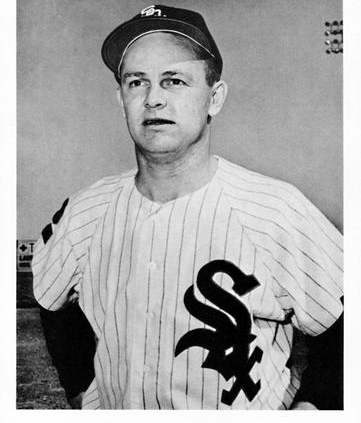

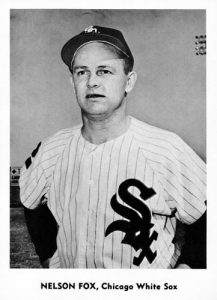

Nellie Fox

Nellie Fox was the heart of the 1959 Go-Go White Sox, the team that brought Chicago’s South Side its first pennant since the tarnished Black Sox season 40 years earlier. The image of Little Nel in his batting stance has become iconic — a choked-up grip on his bottle bat with a wad of chewing tobacco bulging in his cheek. Fox was an unimpressive physical specimen at 5-feet-9 without much innate athletic ability, but determination and opportunity helped a gritty kid with a burning love for the game become a perennial all-star and ultimately a Hall of Famer. Nellie Fox won a Most Valuable Player Award, spent 12 years as an All-Star, won three Gold Glove Awards, and was a dominant force at his position for over a decade.

Nellie Fox was the heart of the 1959 Go-Go White Sox, the team that brought Chicago’s South Side its first pennant since the tarnished Black Sox season 40 years earlier. The image of Little Nel in his batting stance has become iconic — a choked-up grip on his bottle bat with a wad of chewing tobacco bulging in his cheek. Fox was an unimpressive physical specimen at 5-feet-9 without much innate athletic ability, but determination and opportunity helped a gritty kid with a burning love for the game become a perennial all-star and ultimately a Hall of Famer. Nellie Fox won a Most Valuable Player Award, spent 12 years as an All-Star, won three Gold Glove Awards, and was a dominant force at his position for over a decade.

Jacob Nelson Fox — he was always known by his middle name — was born on Christmas Day 1927 in St. Thomas, Pennsylvania, a small town in Franklin County about 30 miles west of Gettysburg. Nellie’s father, Jacob L. Fox, known as Jake, was born on a farm but earned his living as a carpenter. Jake loved baseball and played second base on the St. Thomas town team. He was known as a hard-nosed player and a good bunter, traits he passed on to his son. The Fox family has a picture of young Nelson at the age of 2, holding a homemade bat designed by his father. Even then, Fox was swinging the bat left-handed.

Nelson was the youngest of three brothers. One of them, Frank, died tragically at the age of 3; the other, Wayne, who was seven years Nelson’s senior, shared the Fox family’s love for baseball. As a boy Nelson was often called by the nickname Pug; he wasn’t referred to as Nellie until he began his professional baseball career. Nelson loved all sports, but baseball and soccer were his favorites. “I think I liked soccer better than baseball for a while,” Fox told a writer. “I was only about 130 pounds, but I liked the contact. I liked to mix it up.”1

Fox soon turned most of his attention to baseball, starting out as the mascot and batboy for the St. Thomas town team. He constantly pressured his father and the St. Thomas coach to put him into a game, and when he was given his first opportunity at the age of 10, he amazed everyone by getting a pinch-hit single off a pitcher who was considered the best in the area. Eventually he joined his dad in the St. Thomas lineup, playing first base while Jake manned second. He played ball almost anywhere he could find a team: on the St. Thomas High School team, in American Legion ball, and in the nearby Chambersburg Twilight League. As a teenager he also took on a lifelong habit that would become of his trademarks: chewing tobacco.

Fox was never much of a student: In class he was known to hide sports books or magazines in his notebook and read them when he was supposed to be studying. By the age of 16 he had decided that he wanted to make baseball his career. “I had to be a ballplayer,” he said. “I wasn’t very good at school and I didn’t have any outside hobbies. I played ball. That’s what I did.”2 His mother, Mae, was concerned about Nelson’s future, and one day early in 1944, she wrote a letter to Connie Mack, owner/manager of the Philadelphia A’s. “My boy is baseball crazy,” she wrote. “He won’t study in school. … He worries me to death. … All he talks about is you and the Athletics.”3 Mack wrote back that if her son actually had talent, it was possible to make a living playing ball. “I may one of these days be able to help him,” Mack wrote.4

Due to wartime travel restrictions, the A’s were holding 1944 spring training in Frederick, Maryland, about 50 miles from St. Thomas, and like most major-league teams, the club was holding open tryouts in an effort to fill its war-depleted farm system. With the encouragement they’d received from Mack’s letter, Jake and Mae decided to take Nelson to the camp to try out for the team. Though they didn’t tell Nelson, the Foxes hoped that the A’s would tell their son that he would be better off staying in school.

So in a story that seems like something out of a 1940s B movie, Jake and Nelson drove to Frederick, found the A’s hotel, introduced themselves to Connie Mack, and got a chance to try out for the team. (Fox later squelched the oft-repeated story that he showed up at the A’s camp smoking a big cigar.) According to Philadelphia sportswriter Stan Baumgartner, “(Coach) Earle Mack had difficulty finding a small enough uniform to fit the boy.”5 Though he was almost ridiculously short for a first baseman at no more than 5-feet-6, Fox made a good impression on Mack. According to a story in the Frederick Post, “Connie Mack liked the way the youth conducted himself at the plate and his technique of handling low throws to the initial sack.”6 To Jake and Mae’s surprise, the A’s decided to offer the 16-year-old Fox a contract to join their minor-league system. “(Mack) probably thought the boy was good enough for Class D,” said Jake, “and that he would get as much education by being around with a baseball team as he would in high school.”7

After using him in a few exhibition games, the A’s sent Fox to the Class-B Interstate League’s Lancaster Red Roses, managed by Lena Blackburne. Fox immediately showed some talent, batting .325 while playing both first base and the outfield. It was no surprise that he was not a slugger, with no home runs in 24 games, though he did drive in 12 runs. Nellie was later sent down to the Jamestown Falcons of the Pony League (Class D) for 56 games and hit .304, again with no home runs.

Fox was back with Lancaster in 1945 and hit .314 in 140 games. Moved to second base, the position he would play for the rest of his career, he led the league in hits and runs and hit his first professional home run. However, Fox did not have an opportunity to immediately follow up on this strong showing, as he spent the 1946 season in the military, stationed in Korea. Perhaps the most notable occurrence in his life that year was his engagement to Joanne Statler on Christmas Day 1946. The two had met when both were in high school; “I was a freshman and he was my first date,” said Joanne, recalling that they attended a Christmas dance.8

Fox was again with Lancaster in 1947, hitting .281 with one home run and 22 RBIs. He was called up to the Athletics very briefly that year and appeared in seven games, going hitless in three at-bats. He spent the 1948 season at Lincoln of the Class-A Western League, hitting .311. He led the league in hits and was named to the All-Star team. He and Joanne were married in Lincoln on June 30; the couple would have two daughters, Bonnie and Tracy. Later in the season, Fox was called up to the big club again and played three games at the end of the season, hitting .154 in 13 at-bats.

In 1949 Fox stayed with the Athletics all year, playing behind Pete Suder, who was in his seventh year with the club and had long had a lock on the second-base job. Fox played 88 games and hit .255 with no homers and only eight extra-base hits. He had desire but there were holes in his game, most significantly the inability to produce consistently at the plate. Connie Mack, often a masterful judge of talent, must have felt that Fox was never going to be more than a journeyman, because the A’s put him on the trade market after the season. Connie Mack badly underestimated Nellie Fox.

Shortly after the 1949 season, the A’s traded Fox to the White Sox for catcher Joe Tipton. This could not have been terrific news for Fox, who was leaving a Philadelphia team that had a solid, professional second baseman in Suder in front of him to a club that had Cass Michaels, the American League’s starting second baseman in the 1949 All-Star Game, patrolling the middle.

After beginning the 1950 season as a backup to Michaels, Fox caught a break when the Sox traded Michaels to Washington on May 31 in a multiplayer deal which netted them slugging first baseman Eddie Robinson. Infielder Al Kozar, who came along with Robinson as part of the deal, was expected to be Michaels’ replacement, but Kozar promptly hurt his back hitting a home run against the Yankees. Given an opportunity to play every day, Fox was a bust, hitting .247 with no home runs and 30 RBIs in 130 games. His most impressive traits continued to be his determination and competitive fire. “Nellie was the greatest competitor I ever played with,” recalled Billy Pierce, Fox’s longtime teammate as well as his roommate for 11 years. “Baseball, gin rummy, bowling … whatever he played, he just loved to compete.”9 Getting Fox to hustle and work was never an issue for any man who ever managed him. If anything, those who managed Fox wanted him to take an occasional break.

The White Sox were training in Pasadena, California, in 1951, and Fox was anything but a lock to make the Opening Day roster. “Nellie called me at home from spring training that year,” recalled Joanne Fox, “and said, ‘I don’t think they’re going to keep me. It looks they’re going to send me back to the minors.’”10 And in fact the White Sox had already made a tentative decision to sell Fox to the Portland club of the Pacific Coast League. But Fox had a supporter in White Sox coach Ray Berres. Berres told new manager Paul Richards, “He can play. He’ll play for you if he has to play on crutches.”11

Richards adopted Fox as a project. Former Yankee second base great Joe Gordon worked with Fox on his fielding. A particular focus was turning the double play. “It was brutal the way Fox was pivoting,” Richards commented later. “I’m surprised he didn’t get hurt making the pivot the way he was dragging his foot across the bag.”12 The drills with Gordon paid off, thanks in good part to Fox’s determination. “He made himself into a good second baseman just by working so hard,” said Billy Pierce.13

As a hitter, Fox did have one amazing ability — making contact with the ball. He struck out only once in every 48 plate appearances during his career, and never more than 18 times in a season. But the rest of his offensive game needed work, and White Sox coach Doc Cramer took Fox under his wing. The former Athletics/Red Sox/Tigers outfielder worked with Fox on his hitting, particularly stopping him from lunging at the ball. Cramer also suggested the use of a bottle bat. “Prior to that Nellie had been using a thin-handled bat,” said Billy Pierce. “He was pulling the ball too much, but after Cramer gave him a thicker-handled bat, Nellie began spraying the ball all over the field.”14 Richards also worked with Fox on bunting, and before long, according to Pierce, Fox was the best bunter in baseball among left-handed hitters.

The 1951 season was the turning point in Fox’s career. One-third of the way through this breakout year, he was hitting .364 and the Sox were in first place. That July he was the American League’s starting second basemen in the All-Star Game. He hit only four home runs with 55 RBIs but finished this stellar season with a .313 batting average which was good enough for fifth in the AL. He also tied for second in the league in both hits and triples. His performance helped the club improve to an 81-73 record after seven sub-.500 seasons, finishing in fourth place. This season was the template for the next decade for the Sox and for Nellie Fox — gritty, solid, fundamentally sound baseball. Sox fans had a burgeoning star that they could identify with.

The breakthrough season in 1951 established Fox as a star, and he continued to embellish his reputation over the next decade. Making the American League All-Star team every year from 1951 through 1961, Fox led the league in hits four times during the 1950s and scored 100 or more runs in four straight seasons (1954-57). In the field, Fox led AL second basemen in total chances for nine straight seasons (1952-60), in double plays five times and in fielding percentage four times. In the eight-season span from 1952 through 1959, Fox finished in the top 10 of the American League’s Most Valuable Player voting six times.

But while Fox’s career continued to flourish, the 1950s were often a maddening time for the White Sox and their fans. The 1954 season was typical. Fox had one of the best years of his career, setting career highs with 201 hits, 111 runs scored, 16 stolen bases, and a .319 batting average. He also led the league in games played with 155 while striking only 12 times in 706 plate appearances. Fox’s performance helped the White Sox win 94 games, the most for any Sox club since 1920. But the team still finished a distant third behind the Indians and Yankees.

Paul Richards left the White Sox to take over the Baltimore Orioles at the tail end of the 1954 season, and Marty Marion took over as manager. Neither Richards nor Marion could break the club’s streak of third-place finishes, which reached five in a row in 1956, but on August 6, 1955, Marion did break Fox’s streak of consecutive games played at 274. Giving Nellie a day off did not sit well with Fox. While Fox referred to it as “the most miserable day I ever spent in baseball,” Marion said, “It was the most miserable day of my life too — having to listen to him gripe from the bench.”15 The next day Fox started a new streak that lasted 798 games — an all-time record for second basemen.

The third-place finish under Marion in 1956 marked the arrival of rookie shortstop Luis Aparicio, who took over after Fox’s previous double-play partner, Chico Carrasquel, was traded to Cleveland. Though Carrasquel had been a four-time All-Star, it was immediately evident that the Sox had something special in Aparicio. Luis won the Rookie of the Year award in 1956 and stole 21 bases.

Another important man came to the White Sox in 1957, when Al Lopez took over as manager after one pennant and five second-place finishes with Cleveland. Fox celebrated Lopez’s South Side debut by leading the league in hits, batting .317, and topping AL second basemen in putouts, assists, and double plays. He also became major-league baseball’s first Gold Glove winner at second base and finished fourth in the league’s MVP voting behind Mickey Mantle, Ted Williams, and Roy Sievers. Better still, the Sox finally broke out of their third-place rut by moving up a notch to second place.

After another second-place finish in 1958, the Sox added a final key element when a shrewd new owner, Bill Veeck, bought controlling interest in the team. Veeck brought flamboyance, enthusiasm, and a knack for making things happen to a team that was ready to reach the top, and it all came together for the Sox in 1959.

With Veeck and Lopez providing sound management as well as a belief that the mighty Yankees could finally be had, the White Sox broke out of the gate strongly in ’59 and never looked back. On the field, the club was led by the determined veteran Fox, the speed of Aparicio and Jim Landis, and the solid catching and power hitting of veteran receiver Sherm Lollar. The pitching staff was excellent with Early Wynn, Billy Pierce, and Bob Shaw leading the starting rotation. The bullpen featured two relief aces in Jerry Staley and Turk Lown.

Fox batted .306 with two homers and 70 RBIs in 1959. He was first in the AL in at-bats and second in both hits and doubles. He batted .383 with runners in scoring position. In the field he led the league in putouts, assists, and fielding average while being voted the league’s starting second baseman in the All-Star Game for the fifth straight year. The importance of Fox to this team could not be overstated. Owner Veeck put it well when he wrote that the Sox needed Nellie “no more than your baby needs milk.”16

After beating out the Indians and Yankees for the American League pennant, the Sox faced a Dodgers team making their first World Series appearance since the move to Los Angeles the year before. This was not a dominant Dodgers team of the Brooklyn years but one that took the pennant — barely — with only 88 victories. Two of those wins had come in a best-of-three playoff series with the Milwaukee Braves, who had tied the Dodgers for first place. Sox fans had reason to be hopeful.

The Series began in Comiskey Park, and Game One could not have gone better for the White Sox, who crushed the Dodgers, 11-0, behind the pitching of Early Wynn and two homers from late-season addition Ted Kluszewski. Fox contributed by going 1-for-4 with a walk and two runs scored. But the Dodgers took Game Two by 4-3, then won Games Three and Four as the Series moved to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, a football stadium whose left-field wall was less than ideal for Chicago’s pitching-and-defense club. The Sox kept the Series alive by beating Sandy Koufax, 1-0, in Game Five, but back in Chicago, the Dodgers routed Wynn and wrapped up the Series with a 9-3 victory in Game Six. It was a disappointing finish, but the White Sox could hardly blame Fox, who led the team with a .375 World Series batting average. Fox wrapped up a memorable year by winning another Gold Glove, then being selected as the American League’s Most Valuable Player.

But 1959 turned out to be a peak for both Fox and the White Sox, who would not reach another World Series for 46 years. Veeck made a flurry of deals prior to the 1960 season, trading away young talent to acquire power hitters Minnie Minoso, Roy Sievers, and Gene Freese, but the Sox dropped back to third place while Fox’s average dropped 17 points to .289. In 1961 the Sox fell to fourth place and the 33-year-old Fox was showing signs of age, as his batting average fell to .251. The decline of the Sox continued in 1962, when the team fell to fifth place. Fox raised his batting average to .267, but failed to make the AL All-Star team for the first time since 1950.

In 1963, the White Sox rebounded to a second-place finish, with Fox batting .260 and again leading AL second basemen in fielding average. He was named an All-Star for the 12th and final time. But the White Sox were trying to break in younger players, and Fox’s 14-year stint with the club finally came to an end in December of 1963, when he was traded to the Houston Colt .45s for pitcher Jim Golden and outfielder Danny Murphy. There were indications that had Fox remained with the Sox, he might no longer have had his starting position.

In Houston, Fox was reunited with Paul Richards, now general manager of the fledgling Colt .45s. Fox got into 133 games for the ninth-place .45s in 1964 and batted .265, but he was nearing the end of his playing days. In 1965 he lost the second-base job to future Hall of Famer Joe Morgan. Fox played in only 21 games, hitting .268 before being released by Houston (now known as the Astros) on July 31.

Remaining with Houston, Fox coached for the Astros in 1966 and 1967 under manager Grady Hatton. Joe Morgan credited Fox with helping him maximize his potential as a player, and the two remained friends until Fox’s death. When Morgan was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1990, he said about Fox, “I played with him, and I wouldn’t be standing here today if it wasn’t for what I learned from him. … Above all, Fox impressed upon me the importance of going to the park every day bringing something to help the team. … Nellie Fox was my idol.”17

After leaving Houston, Fox was offered a chance to manage the Braves’ Triple-A farm team at Richmond by Paul Richards, who had become Atlanta’s general manager. Fox turned down the offer, instead joining the Washington Senators’ staff as a coach under Jim Lemon, a former White Sox teammate. Fox remained a Senators coach when Ted Williams took over as manager in 1969, accompanying Williams to Texas when the club became the Texas Rangers in 1972. Fox was highly regarded by the club and given credit for helping several Senators/Rangers hitters, including Frank Howard and Ed Brinkman. Williams thought so highly of Fox that he recommended that Fox replace him as manager when he resigned after the 1972 season. Instead, the job went to Billy Martin. It wasn’t the first time Fox had failed to get an opportunity to manage a major-league club. He had previously been a candidate to manage the White Sox when Don Gutteridge was let go late in the 1970 season, but lost out to Chuck Tanner.

Fox was offered a chance to remain with the Rangers as a minor-league manager, but decided to retire instead. Returning home to St. Thomas, Fox co-owned and operated a bowling center, Nellie Fox Bowl, which he had opened in 1956 in nearby Chambersburg (the bowling center was still in operation with the same name in 2008, long after the Fox family had sold its interest). He also played an occasional round of golf and hunted deer and small game with his beagles, Barney and Nellie. A hometown friend, Clark Gillan, recalled, “Nellie was a dead shot. Man, he could hit anything.”18 Fox also loved Penn State football and frequently attended Nittany Lions’ home games.

“I believe that if (Fox) had not gotten sick, that he would have gotten back into baseball after a couple of years,” said Joanne Fox.19 But in the summer of 1975, Nellie was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer. Many former teammates visited him at the University of Maryland’s Baltimore Cancer Research Center. After Bill Veeck came home from seeing him, his wife, Mary Frances, said, “That was one of the few times I saw Bill cry.”20 At the time Veeck was involved in negotiations to repurchase the White Sox, and, according to Joanne Fox, he told Fox that he wanted him to manage the team for him.

It wasn’t to be; Fox died on December 1, 1975, 24 days before what would have been his 48th birthday. Jim Lemon commented that the cancer “had to be incurable because if it wasn’t, Nellie would have beat it.”21 Fox was buried in his hometown at St. Thomas Cemetery.

Nellie Fox’s posthumous road to the Hall of Fame was reminiscent of his struggles as a player fighting and scraping for his spot in baseball history. He barely missed election in 1985, his final year of eligibility in the annual BBWAA balloting, finishing with 74.7 percent of the vote and falling just two votes short of the requisite 75 percent, the smallest margin in the history of the Hall of Fame. Veteran Chicago writer Jerome Holtzman argued that, in line with baseball’s tradition of rounding off percentages, Fox should have been credited with the necessary total of 75 percent, but Hall of Fame officials disagreed.

Fox’s Hall of Fame candidacy then moved to the Veterans Committee, and another lengthy battle ensued. For several years Fox fell short in the committee voting, and there were reports that his former manager Al Lopez, a committee member, was working to block Fox’s induction (or at least doing nothing to help it). In 1996, with Lopez now gone from the committee, Fox finally received the necessary 75 percent of the vote, but the committee was allowed to elect only one candidate per year; Jim Bunning had received one more vote than Fox, so Nellie missed again.

However, Fox’s fans never gave up and many people lobbied for his election. In 1997, he finally landed his place in Cooperstown. Speaking at Fox’s induction ceremony that August, Joanne Fox said: “He played with all his heart, all his passion, and with every ounce of his being — that was the best way he could show his appreciation to all those who helped him learn the game that became his life.”22 It was never the easy way for Nellie Fox but, as always, determination and grit would get him there.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda.

This biography was published in “1972 Texas Rangers: The Team that Couldn’t Hit” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

http://www.baseball-almanac.com/deaths/nellie_fox_obituary.shtml

http://web.baseballhalloffame.org/hofers/vetcom.jsp

http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Interstate_League

http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Nellie_Fox

http://www.jockbio.com/Classic/Fox/Fox_bio.html

http://www.philadelphiaathletics.org/event/fox2001.html

http://www.philadelphiaathletics.org/trail/fox.html

Alexander, Charles C. Our Game (New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1991).

The Baseball Encyclopedia (Toronto: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1993).

Enders, Eric. 100 Years of the World Series (New York: Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc., 2003).

Johnson, Lloyd and Brenda Ward. Who’s Who in Baseball History (Westport, Connecticut: Brompton Books, 1994).

Johnson, Lloyd and Wolff, Miles. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham NC: Baseball America, Inc., 1997).

Vanderberg, Bob. From Lane and Fain to Zisk and Fisk (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1982).

Ray Berres interview, March 8 and 19, 1996, SABR Oral History.

Notes

1 David Gough and Jim Bard, Little Nel: The Nellie Fox Story (Alexandria Virginia: D.L. Megbec Publishing, 2000), 16.

2 Gough and Bard, 20.

3 Ibid.

4 Gough and Bard, 24.

5 Gough and Bard, 23.

6 Gough and Bard, 25.

7 Gough and Bard, 26.

8 Don Zminda interview with Joanne Fox, July 18, 2008.

9 Don Zminda interview with Billy Pierce, July 18, 2008.

10 Joanne Fox interview.

11Ibid..

12 Neil R. Gazel, “Nellie Does Right by White Sox,” Baseball Digest, August 1951.

13 Billy Pierce interview.

14 Ibid.

15 Dave Condon, The Go-Go Chicago White Sox (New York: Coward-McCann, 1960), 132.

16 Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck As In Wreck (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001; originally published 1962), 342.

17 Gough and Bard, 288.

18 Gough and Bard, 271.

19 Joanne Fox interview.

20 Gough and Bard, 277.

21 Associated Press, “Nellie Fox Succumbs of Cancer,” High Point (North Carolina) Enterprise, December 2, 1975.

22 Gough and Bard, 9.

Full Name

Jacob Nelson Fox

Born

December 25, 1927 at St. Thomas, PA (USA)

Died

December 1, 1975 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.