Carl Boles

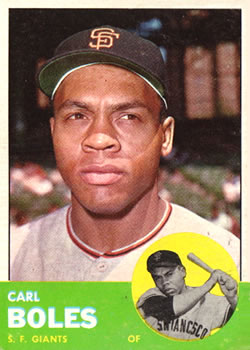

Carl Boles is perhaps best known for being Willie Mays’s doppelganger – a dead ringer for the celebrated superstar. To teammates and opponents, Boles was a fleet center fielder, a solid hitter, and a player whose big-league career with the San Francisco Giants was derailed by a bad break.

Carl Boles is perhaps best known for being Willie Mays’s doppelganger – a dead ringer for the celebrated superstar. To teammates and opponents, Boles was a fleet center fielder, a solid hitter, and a player whose big-league career with the San Francisco Giants was derailed by a bad break.

Boles played on in Japan and had some productive seasons there – and in 1969, his suspicions prompted an investigation that uncovered a massive gambling and game-fixing scandal called “Black Mist.” As a result, 10 players were banned for life. After returning to the U.S. in 1971, Boles continued to serve the game as a scout.

Carl Theodore Boles was born October 31, 1934, in Center Point, Arkansas, to Adrian and Ester (Johnson) Boles. The family farmed. Boles’ paternal and maternal grandfathers owned 300-acre cotton farms 40 miles from Texarkana.

Boles came from a large family. Within a five-mile radius were grandparents, 26 aunts and uncles, and even more cousins. “There was no phone. All you knew was what was going on in the immediate area,” Boles said.1 During summer vacations, Carl, his parents, and his sister Maggie traveled by wagon to Ohio, where they picked tomatoes to earn an extra $300.

As a youth, Carl’s talent for baseball, basketball, and football grew. Summer baseball in the small Arkansas town involved segregated teams on an integrated field. “All the Black kids played on one team and all the white kids played on the other. The whites sat in the stands on one side and the Blacks sat on the other side,” Boles remembered. “One day the white kids wanted to choose up sides because we had been beating them.” It was an invitation that startled the Black youths and produced a lesson Boles would relate to young people in future decades. “Don’t force things. Things will force themselves.”2

During his adolescent years, Boles played on adult men’s baseball teams and held his own against players who were as much as 10 years older. When Boles was in his early teens, his father took steps to raise money to buy his own farm. He moved the family to Kansas City, Missouri, and took a job in a factory. Carl enrolled in a small all-Black vocational high school, R.T. Coles, only to find that it did not field a baseball team. This limited the talented teenager’s baseball playing to Ban Johnson League ball.3 When not playing, Boles relished living in a city with professional baseball. He became a fan of the Kansas City Monarchs and marveled at the skills of Satchel Paige and Hilton Smith. Boles was particularly impressed by a display of Paige’s pitching control. “He sat a guy down at the plate and had him hold a catcher’s glove. Satchel then threw six of eight pitches right into the palm of that glove,” Boles recalled. “The other two hit the side of his mitt.”4

By his senior year at R.T. Coles High, Boles had become a standout on the basketball court and the gridiron. In basketball he teamed with future University of Kansas standout Maurice King to lead the school to the 1953 state title.5 Boles made three steals in the final 11 seconds of the championship game to secure the win. In football Boles was a flashy halfback.6 “One night my coach said that my mother had to come to the game,” he said. “A coach from the University of Nebraska was coming to see me play and was going to offer me a scholarship.”7 A few weeks later, Boles did indeed receive a letter in the mail with the scholarship offer and a bus ticket to Lincoln, Nebraska. However, Boles found that “everything was different. There were only six Blacks in the whole college.”8 But before he could showcase his talent for the Nebraska varsity, professional baseball entered the picture. Gene Thompson, a scout for the New York Giants, had been impressed with Boles’ play for Meyer Metal Craft in the summertime Ban Johnson League. Thompson persuaded Boles to give up football and sign with the Giants. It was a career change that almost ended before it began.

Early in spring training Boles developed a sore right shoulder. “Because of the weather, I couldn’t throw back home. These guys from California and Florida had been throwing all winter,” he explained. “I tried to keep up with them and next thing I know, my arm is hanging.”9 Alex Pómpez watched Boles in drills. The scout asked the outfielder if he had injured the shoulder playing football. “I hurt my left shoulder playing football, not my right shoulder,” Boles said. It seemed that someone made the claim during an evaluation meeting that Boles was damaged goods and advocated his release. Thinking quickly, Pómpez asked Boles if he had a driver’s license. When the player said he did, Pómpez ordered him to pack his things and drive him to his home on Long Island, New York. From there the scout put Boles on a train to join the Giants’ Class D club in Danville, Illinois. “Pómpez saved me from getting released,” said Boles.10

In 1954, his first season of professional baseball, Boles hit .252. He swiped 46 bases, second best in the Mississippi-Ohio Valley League. His 11 triples tied for fifth in the league.11

While the numbers may have impressed others, they did little for Boles. The 19-year-old felt he had failed to establish himself in the game and enlisted in the United States Navy. Less than a week after he signed up, a letter arrived from the New York Giants. It contained a Double-A contract. “I had really screwed up,” Boles said.12 He beseeched Navy brass to be excused from the service to no avail. “My company commander came to me and said, ‘Carl, they are concerned that you are trying to leave. They’re reading your mail.’”13 The revelation made Boles accept his fate.

After just one cruise, a captain recognized Boles’ athletic skills and had him assigned to spend four years in Long Beach, California. He passed exams to become a damage-control specialist and handle firefighting and chemical incidents. However, the bulk of Boles’ time was spent playing on the base’s basketball and baseball teams. “It was a good experience,” he recalled. “We played UCLA, USC, Cal, a lot of junior colleges, and other navy teams.”14 After he watched Boles play in a flag football game, the base athletic director phoned a friend, Ben Agajanian. The NFL standout turned up one day, and after he had watched Boles play, extended an offer of a tryout with the football New York Giants. Boles declined.

When Boles was discharged from the Navy he returned to baseball. In 1959 he was assigned to the Giants’ Class B farm team in the Northwest League, the Eugene Emeralds. Despite having been away from professional baseball for four years, Boles hit .308. He spent both the 1960 and 1961 seasons in the Single-A Eastern League with the Giants’ farm club in Springfield, Massachusetts. In 1960 Boles batted .283 with 10 home runs and 59 runs batted in, impressing teammate Paul Doyle. “He could really run. He could hit, and he was pretty good in the outfield,” Doyle recalled.15 In 1961, Boles raised his average to .296, but hit just seven homers and stole only five bases.

During spring training before the 1962 season, Boles saw little playing time with the Giants’ Double-A farm club, the El Paso Sun Kings. Having already spent two seasons in Single-A ball, Boles became convinced that the Giants did not have plans for him. One night after workouts he packed his bags and quit. The next morning El Paso manager George Genovese was startled to learn of Boles’ departure. Genovese dispatched a teammate, Charlie Dees, to find the AWOL outfielder.16 “I had an aunt in the area, and I was staying with her,” Boles recalled.17 He was surprised when Dees showed up at her doorstep to say Genovese wanted him back. The manager explained that he had decided at the beginning of spring training that Boles would be his center fielder. The manager was merely giving other players a look in the outfield to showcase them for other managers in the Giants’ farm system.18

Once the season began, Boles’ torrid hitting helped El Paso shoot to the top of the Texas League standings. In June he enjoyed the most productive game of his professional career. He hit three home runs and had six runs batted in a 14-10 El Paso win over Albuquerque.19 By mid-July Boles was fourth in the league in batting with a .340 average.20 He was selected to play in the Texas League all-star game and banged out a single and a double in his side’s 2-1 win.21

In late July, Carl Hubbell – the Giants’ farm director – joined the El Paso club to evaluate players.22 He confided to Genovese that he was concerned about the outfield depth in San Francisco. “He said, ‘Mota’s dead in the water,’” recalled Genovese.23 Manny Mota was batting a paltry .176. Genovese suggested that Hubbell stick around for a few days to watch Boles. Hubbell agreed. By the time Hubbell caught a flight back to San Francisco, a change was in the works.

On July 30, 1962, Boles was taking an early afternoon nap when the telephone in his Albuquerque hotel room rang. Boles heard the caller say that he was being called up to the Giants. Convinced it was a prank, Boles went back to sleep. An hour later, loud pounding on his hotel-room door woke the sleeping outfielder. He found his manager, agitated and hollering, “What’s the matter with you! The taxi’s been waiting!” Boles was shocked.24

In San Francisco, Hubbell told the press that Boles was “an aggressive outfielder. He’ll run into a brick wall to make a catch.”25 Boles left El Paso with a .337 batting average and 18 home runs.26 Three days after he joined the Giants, Boles made his major-league debut and struck out against Chicago’s Dick Ellsworth. Six nights later, on August 8, Boles got his first major-league hit, a pinch-hit single at home off Roger Craig in a 5-2 loss to the New York Mets. After sitting for another week, he was sent in to pinch run for Ed Bailey in the seventh inning of a game against the Cubs. Boles stayed in the game and got another hit in the ninth inning. Giants manager Alvin Dark’s confidence in the rookie grew. The Giants’ manager used him for pinch-hitting and spot starts against left-handed pitchers.

During Boles’ third week in the big leagues, the Giants traveled to New York for a series with the fledgling Mets. It was only the second time the Giants had played in New York since their move to San Francisco five years earlier. A large crowd of 33,569 filled the Giants’ old ballpark, the Polo Grounds. “When I came out of the clubhouse and walked on the field, I got a standing ovation. People were clapping and yelling. I tipped my hat and took a bow. When I got closer to the dugout, I could hear mumbling, then the fans started booing. My number was 14. Willie was 24.”27 The crowd had mistaken Boles for Mays.28 At 5’11” and 185 pounds, Boles was similar in stature to Mays and, as Boles was 3½ years younger than Mays, Boles probably more closely resembled the Mays that New Yorkers remembered from 1957.

Mays recognized the fans’ confusion and used it to his advantage. From that night on, “Willie had me get off the bus first,” Boles said. “I would draw the crowd and he could exit without fanfare. People would holler, ‘Willie, sign my autograph.’ By the time it would take to explain, it was just easier to go ahead and sign.”29 The next day was a Thursday day game. Boles started in left field, batting second ahead of Mays, and played the entire ten innings as the Giants won, 2-1. Although Boles made an error that led to the Mets only run, he also had two hits off Mets lefty Alvin Jackson and reached on an error himself.30 It was his only multi-hit game in the majors. The attendance was 18,815.

Another gaffe involving Boles and Mays occurred in September. During a game in Cincinnati Mays collapsed in the Giants’ dugout and was hospitalized. Doctors determined that he was suffering from exhaustion.31 When Mays returned to the team two nights later, a wire service photographer snapped a picture of the Giants’ star which was distributed nationally. Several newspapers ran the photo heralding Mays’ return – only the subject in the picture wasn’t Mays; it was Carl Boles.32

During the remainder of Boles’ time in the Giants organization, his similarity to Mays would become a source of humor. “We went to Tucson for a spring-training game, and Carl got off the bus first,” recalled former Giant minor leaguer Bob Bishop. “The fans were all around him. Willie got off last and walked right by. Nobody noticed him.”33

Throughout September, the Giants dueled the Los Angeles Dodgers for the National League pennant. On the final day of the 1962 regular season, the Giants defeated Houston, 2-1, while the Dodgers lost to St. Louis, 1-0, to finish in a tie for first place. A three-game playoff would decide which team went to the World Series. San Francisco won the first game, 8-0. Entering the eighth inning of game two, the Giants trailed, 7-5. Jim Davenport and Mays opened the inning with singles. Ed Bailey then singled to center field to score Davenport, but Mays was thrown out trying to go from first to third. Alvin Dark sent Boles in to pinch-run for the slow-footed Bailey. Orlando Cepeda then hit a line drive that Frank Howard misplayed in right field. Boles didn’t stop running until he was on third base. When John Orsino flied out to center field, Boles dashed home to tie the game, 7-7. The Dodgers would rally in the bottom of the ninth, however, to win, 8-7.

The following afternoon the Giants secured their first trip to the World Series since moving to the West Coast, with a 6-4 win in Los Angeles. That night more than 50,000 fans waited at San Francisco International Airport for the team to return.34 When fans ran onto the tarmac the flight was diverted to a maintenance facility two miles away. Somehow people found out and close to 1,000 were waiting when the players exited the plane. A mob surrounded the team bus. In their excitement, they shook the bus and broke windows. “What do I do?” asked the bus driver. “Just throw ’em Boles and let’s get out of here,” came the shout from a player seated near the rear.35 In the World Series, which the Yankees won in seven games, Boles did not see action.

For the 1962 season, Boles appeared in 19 games but had just 25 plate appearances. He laid down one sacrifice bunt, but never drew a walk or had an extra-base hit. Nevertheless, his nine singles in 24 at-bats yielded a .375 batting average. As he never appeared in the majors again, this became his lifetime batting average. As his Adjusted OPS+ came in at 104, he will forever be an above average major-league hitter.

When he arrived for spring training in 1963, Boles carried high hopes. Manny Mota had been traded to Houston. Orlando Cepeda remained home in Puerto Rico in a salary dispute. “Alvin Dark told me ‘just take it easy. You’re going to be my left fielder,’” Boles said.36 In the Giants’ second exhibition game, an 18-2 loss to the California Angels, Dark used Boles in right field. It was a position he hadn’t previously played. “I went back on a ball,” Boles said, “and I forgot to find my wall.”37 The resulting collision left Boles with a broken right ankle. The outfielder spent two months in a walking cast at his home in Kansas City. He joined the Giants’ Tacoma farm club in the Pacific Coast League, but when he tried to resume playing, Boles experienced pain in the ankle. Doctors were forced to surgically re-break the ankle and perform a bone-graft procedure.38 It would be November before Boles would receive clearance to resume activities.

Not long after, Boles got a call from his El Paso manager, George Genovese, who was managing Orientales in the Venezuelan winter league. Genovese invited Boles to play for Orientales and Boles eagerly accepted.39 “When he met me at the airport, he said, ‘Carl, I want you to show these guys how to win,’” Boles said.40 The outfielder batted .323 and was an all-star.41 “George told me that the Red Sox and the Mets had talked to the Giants about trading for me, but the Giants wanted too much in return,” Boles said.42

When Boles visited his parents’ home in Arkansas, he carried a letter. It was from a fan in Venezuela and was written in Spanish. He sought someone who could translate the contents and was directed to a school in the nearby town of Hope. When Boles met the teacher, his request for translation help evolved into one for a date. Soon, Carl and Mercedes Cabassa were seeing each other regularly.

In 1964 younger prospects José Cardenal and Jesús Alou surpassed Boles, who spent the season with Tacoma. He struggled, batting only .232 with six home runs. Following the season Boles, then 30, accepted an offer from the Giants to become a scout. He was assigned to cover Oakland as well as parts of California to the north. 43

Before the 1966 season, Boles received an offer to resume his playing career in Japan. He enthusiastically agreed and spent five and a half seasons there. In his first season with the Kintetsu Buffaloes, Boles hit 26 home runs, drove in 57 runs, and batted .261.44 Several thousand miles from home, Boles found himself missing his fiancée, Mercedes Cabassa. He pleaded with her to come to Japan. When she arrived, the couple went to the United States Embassy, where they were married.

Boles’ second season in Japan was even better than his first. He belted 31 home runs and batted .305. Boles was named to the all-star team. After three seasons with the Buffaloes, he switched in 1969 to the Nishitetsu Lions. During that season, Boles voiced concern to sportswriters that several teammates appeared to him to be playing in a suspect way. This led to a massive scandal that became known as Black Mist. Investigations by Japanese newspapers, government committees, and Nippon Professional Baseball found that 22 players had conspired with the yakuza (Japanese organized crime) to fix games. Of the 22, 10 were banned for life, five received suspensions of varying lengths, and three retired from baseball. Four who were loosely connected to the scandal but whose actions were deemed innocuous received harsh warnings.45

In 1970 Boles hit 28 home runs for the Lions. During the 1971 season, Mercedes Boles received an offer of a teaching job in San Francisco. The couple decided it was the right time to return to the United States. In his final season in Japan, Boles appeared in just 33 games, but had nine homers and 21 RBIs to go with a .285 batting average. The Giants had given Boles an open invitation to return to their scouting staff when he concluded his playing career, and he took the team up on the offer.46

SABR’s Scouts Committee has no record indicating that Boles was involved with the signing of any big-leaguers. However, he recommended at least two future stars from the Bay Area whom the Giants did not draft – Mike Norris and Rickey Henderson – which didn’t sit well with Boles.47

In 2004 both Boles and his wife retired and moved to Tampa, Florida. There Boles established the Baseball 4 Kids Foundation, which helped provide Little League opportunities for children who otherwise would not be able to financially afford to play. He also assisted the Tampa Bay Rays’ community relations department.

Carl Boles died on April 8, 2022 at the age of 87. He is buried at Center Point Cemetery in Center Point, Arkansas.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Jeff Findley. Thanks also to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Sources

Personal Interviews

Carl Boles, via telephone interview on May 30, 2017, and in-person conversation on August 26, 2018.

Websites

Ancestry.com, BackToBaseball.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Paperofrecord.com, Pelotabinaria,com.ve (Registro Histórico Estadístico del Beisbol Profesional Venezolano), Retrosheet.org.

Publications

Genovese George, and Dan Taylor, A Scout’s Report, My 70 Years in Baseball, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company (2015).

Notes

1 Carl Boles, telephone interview with author, May 30, 2017 (“Boles interview”).

2 Boles interview.

3 “A Strong Meyer Team,” Kansas City Star, April 21, 1953: 20.

4 Boles interview.

5 “Singing Strings Summary,” Lincoln Clarion, March 20, 1953: 7.

6 “R. T. Coles Romps 33-0,” Kansas City Star, October 26, 1952: 3.

7 Boles interview.

8 Boles interview.

9 Boles interview.

10 Boles interview.

11 Baseball-Reference.com, 1954 Mississippi-Ohio Valley League Batting Leaders.

12 Carl Boles, in-person conversation with author, August 26, 2018 (“Boles conversation”).

13 Boles conversation.

14 Boles conversation.

15 Paul Doyle, conversation with author, June 1, 2018.

16 George Genovese and Dan Taylor, A Scout’s Report: My 70 Years in Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2015), 119.

17 Boles conversation.

18 Genovese and Taylor, A Scout’s Report, 119.

19 “Boles Turns Three-Homer Feat,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1962: 35.

20 “League Leaders,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1962: 47.

21 “South Rises, 2-1” El Paso Herald Post, July 18, 1962: 18.

22 Chuck Whitlock, “Here’s How,” El Paso Times, July 29, 1962: 32.

23 George Genovese, conversation with author, October 4, 2009 (“Genovese conversation”).

24 Genovese conversation.

25 Jack McDonald, “Giants Obtain Speedy Boles,” The Sporting News. August 11, 1962.

26 “Boles Joins Giants, Mota, Schurr, Report to Kings,” El Paso Times, August 1, 1962: 12.

27 Boles conversation.

28 Bob Stevens, “Carl Boles, Mays’ Double, Mistaken for Giants Star,” The Sporting News, September 29, 1962: 9.

29 Boles interview.

30 Dick Young, “Giants Shake Mets in 10th, 2-1;” Daily News (New York, New York), August 24, 1962: 44.

31 Dan Walton, “Sports-Log,” Tacoma News Tribune, June 2, 1963: 29.

32 Walton, “Sports-Log.”

33 Bob Bishop, conversation with author, September 18, 2015.

34 Dick O’Connor, “Giants nearly fanned to death in extra inning squeeze play,” Peninsula Times Tribune, October 4, 1962: 1.

35 Dan Walton, “Sports-Log.”

36 Boles interview.

37 Boles interview.

38 Harry Jupiter, “Giants Trample Redlegs,” San Francisco Examiner, August 24, 1963: 37.

39 Genovese and Taylor, A Scout’s Report, 127.

40 Boles interview.

41 Eduardo Moncada, “Double Dose of Woe for Skipper Bristol,” The Sporting News, February 1, 1964: 25.

42 Boles interview.

43 George Ross, “A Giant in Town,” Oakland Tribune, March 3, 1965: 40.

44 Earl Luebker, “Sports Log,” Tacoma News Tribune, December 6, 1966: 44.

45 Isaac Meyer, “Episode 377,” Facing Backwards Podcast, February 12, 2021.

46 “Carl Boles Will Scout for Giants,” San Angelo Standard-Times, June 8, 1971: 14.

47 Boles interview.

Full Name

Carl Theodore Boles

Born

October 31, 1934 at Center Point, AR (USA)

Died

April 8, 2022 at Tampa, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.