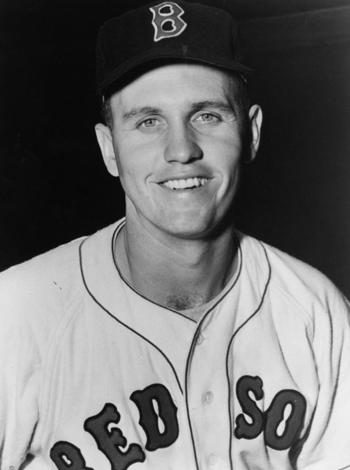

Willard Nixon

During his nine-year major-league career, all with the Boston Red Sox, Willard Lee Nixon never won more than 12 games in a season, and he lost more games than he won. Yet, when he died more than 40 years after his career ended, Time magazine noted his passing in its “Milestones” section, which typically features only celebrities. The accomplishment that earned Nixon this recognition was his uncanny and unexplained (and ultimately unsustainable) ability to beat the mighty New York Yankees, who won eight pennants during his tenure in the American League. Throughout baseball, he was called the “Yankee Killer.”

During his nine-year major-league career, all with the Boston Red Sox, Willard Lee Nixon never won more than 12 games in a season, and he lost more games than he won. Yet, when he died more than 40 years after his career ended, Time magazine noted his passing in its “Milestones” section, which typically features only celebrities. The accomplishment that earned Nixon this recognition was his uncanny and unexplained (and ultimately unsustainable) ability to beat the mighty New York Yankees, who won eight pennants during his tenure in the American League. Throughout baseball, he was called the “Yankee Killer.”

Nixon’s roots were firmly planted in the red clay of his native North Georgia. He was born in the small hamlet of Taylorsville on June 17, 1928, and grew up in neighboring Lindale, Silver Creek, and Rome. While his baseball career took him throughout the United States and beyond, his permanent home was always in Georgia. Both of Willard’s parents, Robert Lee Nixon and Eva Lou Brownlow Nixon, worked in local textile mills. They divorced when Willard was 11 years old, and he lived with his paternal grandparents in Rome for several years before reuniting with his father. By the time he graduated from high school, he was a veteran of four seasons of textile ball, first as part of an informal effort to “keep baseball alive despite wartime conditions”1 and later in the Northwest Georgia Textile League (NWGTL).

By 1945, 17-year-old Nixon was the acknowledged ace of the Pepperell Mills’ pitching staff. The young right-hander compiled a 6-1 record and earned two more victories as Pepperell swept a best-of-three postseason tournament. He opened the 1946 NWGTL season with three shutouts and 33⅔ consecutive scoreless innings, compiling a regular-season record of 12-3. When Pepperell became league champion by winning two postseason series, Nixon was the workhorse—and the show horse. He pitched in six games and played left field in the other four. He won the deciding game of each series and batted .519 (19-for-37) for the postseason, including a game-tying home run in the final game.

In 1947, the Detroit Tigers offered Nixon a contract after graduation from McHenry High, but he chose to accept a grant-in-aid from Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University). In his first game for Auburn, he faced only 19 batters in five innings to beat Mercer University. He compiled an 8-2 season record and led Auburn to a second-place Southeastern Conference finish. Nixon then rejoined Pepperell, 8-1, and again the undisputed star of the postseason. He pitched in five of the six games, winning three, saving one, and losing one. He batted “only” .364 (4-for-11), but three of his four hits were for extra bases for a 1.000 slugging percentage.

In Auburn’s 1948 conference opener, Nixon struck out 20 Ole Miss batters to set a new SEC record. In his next outing, he tossed a no-hitter against the University of Tennessee, striking out 18 batters and walking four. When he next faced the Vols, only a scratch eighth-inning single deprived him of a second no-hitter. In that game, Nixon contributed four hits, including a 370-foot home run, and the Rome News Tribune observed that “folks in Knoxville think that [Nixon] is the greatest college player of all time.” Scouts from 14 major-league teams watched Nixon beat Vanderbilt in the season’s final game, giving him a 10-1 record. His 145 strikeouts set an SEC standard that stood for 39 years. He also led Auburn with a .448 batting average. Two days after the season ended, he signed a contract with the Red Sox. Mace Brown, in the first year of a long Bosox scouting career, proudly predicted that “he can’t miss being a big leaguer.” Every team except the Chicago White Sox and the Philadelphia Athletics had bid for Nixon’s services.

Nixon reportedly was offered bonuses of as much as $30,000 but chose to take less than the $6,000 which would have placed him under the bonus rule. He later explained, “Although nobody in the world needed the money more than I did, I just didn’t think I was good enough to start at the top. I was afraid I might get that money and go up to the majors and flop. Then that bonus money might be all I’d ever get out of baseball.”2

The Sox optioned Nixon to Scranton in the Class A Eastern League; one day before his 20th birthday, he made an impressive debut, pitching an eight-hit shutout against the Wilkes-Barre Barons. Local sportswriter Chic Feldman waxed eloquent about his performance, exclaiming that “the door to a glittering future opened at the stadium last night and in strode Willard Nixon, blond and beautiful (both physically [6’2”, 195 pounds] and baseballically).”3 He closed the regular season with six consecutive victories to compile an 11-5 record and added two postseason complete-game victories as Scranton won the Eastern League Championship.

Willard started the 1949 season with Louisville in the Triple-A American Association. The Colonels got off to a terrible start, and so did Nixon. After recording three losses in four games, he was demoted to the Birmingham Barons in the Double-A Southern Association. He lost his first three games for the Barons, making him 0-6 for the season. On June 6, the hometown fans at historic Rickwood Field greeted Nixon with chants of “War Eagle” (an Auburn cheer) as he warmed up;4 he responded with a “brilliant 3-hitter”5 to beat the Chattanooga Lookouts. He then won 13 of 17 decisions to finish the season at 14-7. His .345 batting average led the Barons.

The highlight of his year was August 15 at Atlanta’s Ponce de Leon Park. With a large contingent of fans from his home town among the 4,996 in the stands and more watching on television at the American Legion clubhouse in Lindale, Willard dominated the Atlanta Crackers. The final score was 5-4, and Nixon pitched all nine innings and drove in all five Baron runs. As Langdon B. Gammon reported, “He was the whole show, producer and star.”6

During spring training in 1950, Nixon struggled with his control and again was optioned to Triple-A Louisville, where he won his first three games and had a record of 11-2 by early July. The Bosox were mired in fourth place, and the pitching corps was getting most of the blame. Manager Joe McCarthy had resigned in mid-June, and his replacement, Steve O’Neill, soon decided that it was time for more change. On July 6, when Nixon was promoted to the parent club, his 97 strikeouts led the American Association, and he was batting .345.

Nixon joined the Red Sox in New York and received his major-league baptism immediately, pitching the last two innings of a July 7 loss and allowing one run on three hits and three walks. He made his first start on July 13 against the White Sox at Fenway Park and got a victory (and his first major-league hit) in a rain-shortened game. By season’s end, Willard had appeared in 22 games, compiling a record of 8-6 with an ERA of 6.04. He started against each of the other seven American League teams and made seven relief appearances. Most observers (and Nixon himself) noted that he needed to improve his control—he had recorded more walks (58) than strikeouts (57) in 101⅓ innings—but everyone agreed that he was ready to be an effective member of the Red Sox pitching staff, and several experts predicted stardom.

During the offseason, as he did throughout his career, Nixon continued to work at Pepperell Mills and stayed in good physical condition by refereeing high-school basketball games and playing golf. Spring training in 1951 was a time of optimism for the Boston Red Sox and for Nixon, starting a pattern that persisted throughout his career. Every spring produced predictions of greater success for the Red Sox in general and for Nixon in particular. The regular seasons never lived up to those rosy forecasts. The Red Sox, who had been consistent pennant contenders in the late 1940s, typically finished third or fourth, and Nixon never achieved the stardom that seemed so likely every spring. He consistently struggled with his control, and he often tired in the middle and late innings and late in the season. He had a tendency to give up runs in bunches—perhaps because he could not always control his emotions. When things went badly, he got angry—usually with himself, sometimes with the umpires—and he did not pitch well when angry.

Nixon spent 1951 shuttling between the bullpen and brief stints as a starter. In August, he pulled a tendon in his right thigh while pitching after a rain delay, and his season went downhill. He finished his first full big-league season with a 7-4 record (4.90 ERA), improving in all key statistical categories and batting .289.

Before the 1952 season, Lou Boudreau replaced O’Neill as manager, and several pitchers with excellent minor-league credentials joined the staff. In April, the Sox offered to trade Nixon to the Athletics, but the deal fell through. He stayed with Boston, but no longer as a member of the starting rotation. He did not make his first appearance until May 6, becoming the 10th Red Sox pitcher to start a game that season. Nixon made the most of that opportunity. Using a new sidearm delivery and a slow curve7, he earned a complete-game victory over Chicago. A shoulder cramp in his next start led to a two-week layoff, and a series of ineffective starts resulted in his juggling three roles for the rest of the season.

Nixon appeared in 33 games—13 as a starter, 10 in relief, and 10 as a left-handed pinch-hitter—as the Red Sox ended the season in sixth place, their worst finish in seven years. He eked out a winning record (5-4) and lowered his ERA slightly to 4.86, but again walked more than he fanned. Injuries plagued him, and coaches and sportswriters suggested that his temper was adversely affecting his performance. During the offseason, Jack Malaney had commented in the Boston Post on Nixon’s tendency to go into a “veritable frenzy when roughed up,” and Ed Costello of the Boston Sunday Herald wrote in August that he “must learn to control his deep-rooted, but not apparent, explosive emotions.”

After a miserable spring in 1953, Nixon did not start a game until May 22, but his win on June 6 was the first of four consecutive complete-game victories, and he threw 21 consecutive scoreless innings over one three-game stretch. In typically modest fashion, Nixon told reporters that his improved performance was due to “luck, pure luck”; although observers cited a “new slow curve and speedy slider”8 and his “added poise and confidence.”9 If the improvement was due to luck, Nixon’s fortunes changed quickly; he did not win another game that year. He struggled to a record of 4-8, his first-ever losing season, and he compiled this dismal record primarily against second-division teams. But he reduced his ERA for the third straight year (from 4.86 to 3.93) and for the first time as a major leaguer gave up fewer hits than innings pitched.

Nixon got his first start of 1954 on April 19 against the Yankees. In six career appearances against the Yankees up to then totaling 20 innings, his record was 0-1—not much of an indicator of what was to come. This time, he allowed only five hits, struck out 10, and earned a 2-1 victory and a spot in the rotation. He faced the Yankees three more times in 1954 and beat them each time. His 1954 record was 11-12, and nine of those victories came against two clubs—the Tigers (five) and the Yankees (four).

Despite his losing record, 1954 was a breakthrough season for Nixon. He pitched 199⅔ innings, and his 11 victories were a new career high. His ERA (4.06) increased slightly, but he had established himself as a dependable starter. During the offseason, Paul Richards, Baltimore’s new manager/general manager, tried to trade for Nixon, whose potential he had praised for years. New Red Sox manager Mike Higgins, who had managed Nixon in Birmingham, expressed his confidence that Willard could be a consistent winner in the majors—especially with the help of new pitching coach Dave “Boo” Ferriss.

A successful spring and his “Yankee Killer” reputation earned Nixon the honor of starting the Red Sox’ 1955 home opener. “Wonderous Willard”10 pitched well, and reliever Ellis Kinder preserved Nixon’s fifth consecutive win over the Yankees. After a shutout of the Washington Senators, Nixon threw a two-hitter in Yankee Stadium to earn his second consecutive 1-0 road victory and his sixth straight win over New York. The Atlanta Constitution crowed, “Dan Topping and Del Webb may think they own the Yankees, but it turns out that Willard Nixon … really does. … He beats them merely by tossing his glove out on the field.”11

As usual, Willard’s success was short-lived. He lost his next start, bounced back with a win, and then made six consecutive winless starts that evened his season record at 4-4. One of those losses ended his winning streak against New York, but he beat the Yankees on July 4, a victory that began a five game winning streak. The final game in the stretch was a 4-1 victory over Whitey Ford, his fourth besting of the Yankees in 1955.. With August only a week old, he had already won a career-high 12 games, but he did not win again that season. In eight starts, he was charged with five losses, including two to the Yankees—one that eliminated the Red Sox from the pennant race and one that clinched the pennant for New York.

During this period, Nixon showed increasingly frequent demonstrations of his legendary temper. After allowing the Tigers four runs in the ninth inning of a 5-4 loss, he splintered Fenway’s locker room door with a metal chair, earning a Boston Traveler headline that read, “Nixon Proves To Be ‘Chairful’ Loser.”12 His displeasure was understandable. What once appeared to be an outstanding season became merely a good one. He finished with a 12-10 record and 4.07 ERA, pitching a career-high 208 innings in 31 starts.

The next spring, pitching coach Ferriss helped Nixon develop a knuckleball and a second curveball and predicted that he could win 20 games.13 Willard pitched well during spring training—even after he fell off an elephant during a team tour of the Ringling Brothers Circus’s winter quarters in Sarasota. He had climbed aboard at the request of a photographer and tumbled off when the elephant took an unexpected bow. He suffered only a few scratches, but earned a new nickname (“Sabu”–after Hollywood’s “Elephant Boy”) and inspired a pun or two, being chided “Tusk! Tusk!” and getting credit for having a “trunkful of new curves.”14

Nixon started for the Sox in the Yankees’ 1956 home opener and lost to the New Yorkers for the third consecutive time. After that game, an ailing right shoulder that had troubled him since March (and perhaps was a result of “elephantitis”) kept him out of action for a month. An orthopedist treated Nixon for a calcium deposit in his shoulder and tendon inflammation. On May 29 Willard faced the Yankees and turned in a masterful performance, carrying a no-hitter into the eighth inning. A teammate’s error cost him a shutout, but he earned his first win of the season.

At midseason, Nixon returned to the rotation despite an ailing back that persisted even after his sore arm improved. He showed no symptoms of back or arm troubles on August 7, when he and Don Larsen faced off at Fenway Park before a standing-room crowd of 36,350. After 10 innings, both starting pitchers were still in the game, and neither had allowed a run. In the 11th, Ted Williams incurred the wrath of the Fenway Faithful by dropping an easy fly ball, but then turned the fans’ boos to cheers by retiring the side with a great catch. As he returned to the dugout, however, Ted showed his disdain for the crowd’s fickleness by spitting toward the stands. The Red Sox won the game in the home half of that inning, and although Willard Nixon had pitched one of the best games of his career and drawn a walk to start the game-winning rally, the headlines went exclusively to Williams, whose “Great Expectorations” earned him a $5,000 fine.

Nixon beat the Yankees (and Larsen) in New York with a two-hit complete game, boosting his career mark to 11-5 against the Yankees. Nixon made six more starts in 1956 and resumed his pattern of alternating wins and losses. In his final start of the season, on September 16, Nixon aggravated his sore arm and had to leave the game in the first inning. His season was over, a season of higher highs and lower lows than ever before—even for a pitcher who himself admitted that “the only consistent thing about me was my inconsistency.”15 Nixon pitched several outstanding games, but he lost six weeks due to his arm trouble.

Throughout the 1957 season, Nixon ignored continuous arm pain and a pulled tendon in his left leg to make regular starts and generally pitched well. During a 14-game midseason stretch, he produced 11 quality starts, but only a 7-7 record. Despite his losing record (12-13), 1957 was one of the better years of Nixon’s career. He overcame chronic arm troubles and a nagging leg injury to complete 11 of his 29 starts and to compile a career-best ERA of 3.68. He also led American League pitchers with a .293 batting average.

When 1958 opened, Nixon had the longest tenure with the Red Sox of any player other than Ted Williams. He opened the season by losing twice to the Yankees. Nixon’s first victory of 1958 (and final major-league win) came in a three-hit complete game against Kansas City. After the Tigers handed him a complete-game loss, manager Higgins used Nixon (on only three days’ rest) in relief against the Yankees. After three effective innings, he weakened and took the loss that evened his career record against New York at 12-12. In his next outing, Nixon lasted only one inning because his arm troubles returned. After the game, he said, “I’m not worried about my arm. This isn’t like the trouble I had the past couple of years. It’s only a temporary thing.”16 Unfortunately, his injury was far from temporary. In his next start, he faced only four hitters and took the loss, bringing his season record to 1-7—worst on the team. It was little consolation that he was leading the team in hitting (.312); it would turn out to be Willard’s last major-league start.

After three weeks of pitching batting practice to test his arm, Nixon made what would be his final major-league appearance on July 4 at Fenway—only three days short of the eighth anniversary of his Red Sox debut. He entered the game in the sixth inning and pitched a scoreless 1⅓ innings before yielding three hits and two runs. Nixon admitted after the game, “I had nothing in that eighth inning. Nothing! … [My arm’s] throbbing like a toothache. It’s really paining me. As things stand, I’m no good to anybody—Mike, myself, the team—anybody!”17 The Red Sox brass obviously agreed; they put Nixon on the disabled list in mid-July, and he went home, where he sold real estate and played golf. Nixon’s 1958 won-loss record (1-7) was by far the worst of his career and cost him a lifetime winning record, dropping his overall record to 69-72.

Nixon did not believe that his career was finished. Over the winter, he told the Atlanta Journal, “I am confident I can pitch again.”18 He reported to the Red Sox’ new spring training site in Scottsdale, Arizona, hoping to earn the roster spot that would garner the added pension benefits that came with being a 10-year veteran. But his arm still bothered him, and on April 4, he received his outright release. He immediately signed with the Minneapolis Millers in the Triple-A American Association, a minor leaguer again.

Despite two trips to the disabled list, he pitched 98 innings in 26 games and compiled a 6-2 record and a respectable 3.58 ERA. When he pitched ineffectively early in the league’s postseason tournament, he was dropped from the active roster and became the first-base coach. In this new role, he saw the Millers qualify for the Junior World Series, which pitted them against the International League champions, the Havana Sugar Kings. After two games in which wintry Minnesota weather kept attendance low, the rest of the seven-game series was shifted to Havana, where the weather was warm and the politics were hot. Fidel Castro had recently overthrown Fulgencio Batista, and the streets were filled with armed soldiers. A wide-eyed Nixon later talked about riding with a taxi driver armed with a “tommy gun.” With Castro attending every game, Havana took the series by winning the deciding seventh game in the bottom of the ninth.

After the 1959 season, Nixon expressed “considerable doubt” that he would ever pitch again. He told his hometown newspaper that he was awaiting a call from the Red Sox and still hoped to “get in ten years either as a player or coach.” When the call finally came, the offer was a position as a scout, and Willard accepted. After five years as a Red Sox scout, covering five Southeastern states, he rejoined Pepperell Mills (now West Point-Pepperell, Inc.) as purchasing agent. In 1968, the Floyd County Board of Commissioners named him clerk of the board. He resigned that position in 1971 to become a county court investigator. He was appointed chief of police for Floyd County in 1973. After four years, Nixon went back to West Point-Pepperell to work in the shipping department. Two years later, he moved to the Floyd County school system, where he served as transportation director until he retired in 1989.

Nixon’s career in law enforcement was somewhat ironic since during his time with the Red Sox he had excelled as a forger. Both teammate Mel Parnell and Don Fitzpatrick, Boston’s clubhouse attendant during the 1950s, attested to Willard’s skill at replicating the signatures of other Red Sox players, especially Ted Williams. Fitzpatrick told it this way: “They’d bring boxes of balls … over to Ted, and he’d say, ‘Give it to Willard.’ He signed hundreds of balls for Williams. That’s why we thought he’d never be traded or released.”19

Willard first learned golf while caddying as a youngster, and he played throughout his baseball career. After that career ended, he became one of the most popular and most successful amateur golfers in Northwest Georgia and maintained this status until heart trouble slowed him down in his early 60s. A pacemaker allowed him to maintain an active lifestyle, but he played considerably less golf. Eventually, however, the debilitating effects of Alzheimer’s disease weakened him and led to the fall that ended his life on December 10, 2000, at the age of 72. He was buried in Rome’s East View Cemetery, leaving behind Nancy (nee Logan), his wife of 52 years; three grown children; seven grandchildren; two great-grandchildren; and a legion of friends and admirers.

In 1971, Nixon was among the seven people chosen for the inaugural class of the Rome-Floyd County Sports Hall of Fame, and he was inducted into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame in 1993. In 2002, a plaque bearing his name was added to the Tiger Trail—a “Walk of Fame” composed of markers embedded in the streets of Auburn, Alabama, to remember athletes who “have brought pride, glory, and honor”20 to the local university.

While Willard Nixon never gained the stardom that many baseball experts predicted for him, he did achieve what many only dream of. He became a major-league baseball player, and despite nagging injuries, he lasted longer than most. Thirty other American League pitchers made their major-league debut in the same year as Nixon, and only three (Lew Burdette, Whitey Ford, and Ray Herbert) pitched longer and won more games. The average career for 1950’s other 25 American League rookie pitchers was 3.6 years.

When he looked back on his years in baseball, Willard himelf said, “I didn’t get the most out of my ability, but I’m happy with [my career]. Baseball’s been good to me. I wouldn’t have had anything if it hadn’t been for baseball. Here I was from a small mill town in Lindale, going to big cities where thousands of people are whooping and hollering at you. It’s been more or less a dream.” But he hadn’t been dreaming; for a few years, the name of that small-town Georgia boy was a household word among Yankee fans and foes everywhere.

Sources

Auburn University Library (especially Joyce Hicks)

Boston Public Library

Ed Costello, “Yankee Killer (Willard Nixon),” in Tom Meany (ed.), The Boston Red Sox (New York: A.S. Barnes and Co, 1956).

Mrs. Nancy Nixon, several extensive interviews, 2006-2007.

Rome/Floyd County Public Library (especially Dawn Hampton).

John Snyder, Red Sox Journal (Cincinnati: Emmis Books, 2006).

Notes

1 Langdon B. Gannon, Rome News Tribune, April 22, 1943.

2 Roger Birtwell, Boston Globe, March 14, 1949.

3 Chic Feldman, Scranton Tribune, June 17, 1948.

4 Jim Mullins, Birmingham Post, June 7, 1949.

5 Walton Lowry, Birmingham News, June 7, 1949.

6 Langdon B. Gammon, Rome News Tribune, “Lindale News,” August 15, 1949.

7 Herb Ralby, Boston Globe, May 7, 1952.

8 Hy Hurwitz, Boston Daily Globe, June 17, 1953.

9 Arthur Sampson, Boston Herald, June 23, 1953.

10 Tony Galli, International News Service (in Rome News Tribune, February 14, 1955).

11 Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 24, 1955.

12 Boston Traveler, September 8, 1955.

13 Tom Monahan, Boston Traveler, March 26, 1956.

14 Harold Kaese, Boston Globe, March 8, 1956.

15 George Kolb, Sarasota Herald-Tribune, March 7, 1957.

16 Tom Monahan, Boston Traveler, June 7, 1958

17 Mike Gilhooly, Boston Evening American, July 5, 1958.

18 Bob Christain, Atlanta Journal, November 20, 1958.

19 Richard Goldstein, New York Times, December 14, 2000.

20 “The Loveliest Village,” Blog Archive (http://www.loveliestvillage.org), October 31, 2006.

Full Name

Willard Lee Nixon

Born

June 17, 1928 at Taylorsville, GA (US)

Died

December 10, 2000 at Rome, GA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.