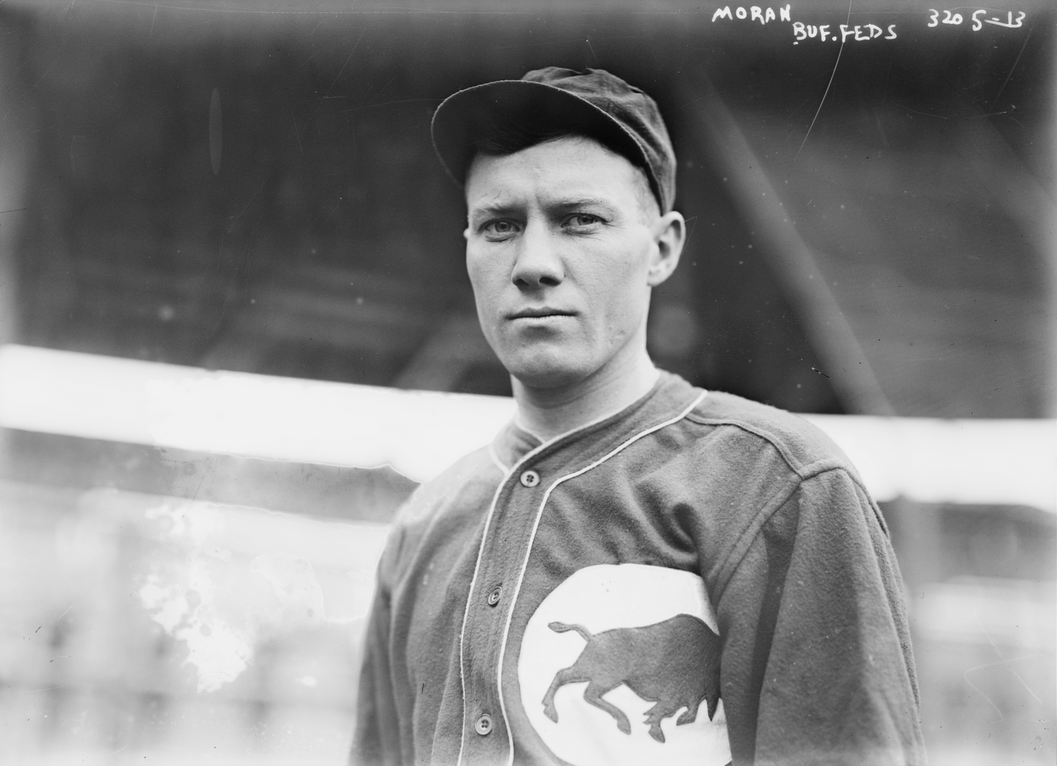

Harry Moran

Harry Moran was born in Slater, West Virginia, on April 2, 1889. He was the son of L. D. (Lorenzey Dow) and Ella Moran, two native-born West Virginians. He was brought into at least a modestly wealthy family. At Harry’s birth L. D. was, according to the 1880 Census, a blacksmith laborer, a trade he had learned while living with his older brother, James.1 On August 16, 1906, L. D. was appointed postmaster of the Wyndal district of Fayette County, West Virginia. Eventually he became superintendent of the local coal mine. Not bad for a man with only a first-grade education. In the 1940 Census he and Ella were still living, respectively 75 and 70 years old.

Harry Moran was born in Slater, West Virginia, on April 2, 1889. He was the son of L. D. (Lorenzey Dow) and Ella Moran, two native-born West Virginians. He was brought into at least a modestly wealthy family. At Harry’s birth L. D. was, according to the 1880 Census, a blacksmith laborer, a trade he had learned while living with his older brother, James.1 On August 16, 1906, L. D. was appointed postmaster of the Wyndal district of Fayette County, West Virginia. Eventually he became superintendent of the local coal mine. Not bad for a man with only a first-grade education. In the 1940 Census he and Ella were still living, respectively 75 and 70 years old.

Harry was the second child born to the Morans. A sister, Bessie, died in infancy. L. D. was a mine superintendent for most of his working life.

As an indicator of the family financial health, Harry attended a private military school for boys for his high-school training. It was Fishburne Military School in Waynesboro, Virginia.2 It had been started a decade before his birth. Still operating in 2019, it is the smallest military school in the United States, with 165 students.

In 1909 Moran entered Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, where he played baseball for three years. In his senior year (1912), he was team captain. In the 1910 and 1911 seasons he lost only one start.

Moran was not only a student/athlete but a young man of many interests. He was president of the university’s Cotillion Club and the Fancy Dress Ball. He loved athletics beyond just baseball. He was president of the Athletic Association, the Athletic Council and the Monogram (varsity) Club. He was also president of the West Virginia Club and “The Sons of Ireland.”

After receiving his undergraduate degree, Moran spent two years in the university’s Law School. He and another Washington and Lee graduate, Chuck Tompkins, whose major-league pitching career consisted of one game with the Cincinnati Reds, assisted their former varsity coach, Al Orth. Moran was interested in anything to do with athletics. At 6-feet-1 and 165 pounds, he certainly fell within specifications sought for pitchers. He was a lefty on the mound and at the plate.

Moran turned down a draft bid from the Detroit Tigers for the 1911 season because he was excited for the prospects of the 1912 Washington and Lee team.3 The team did have a good season, winning 19 games, losing 7, and tying one. Moran was the pitcher of record for the tie game, a 7-7, 11-inning stint against the University of Georgia. He ended the season with a record of 8-1-1 and went out on a high note by reversing his only loss, against A&M of North Carolina. In his last college game, he beat the Aggies 3-0 in his second 11-inning contest of the year. His college signature game was a no-hitter with 20 strikeouts in the 1911 season.

After graduation and at the end of the 1912 collegiate season, Moran signed with the Tigers, an elite team that had won the AL pennant three seasons running from 1907-1909; they had, however, lost all three World Series. They had dropped to third place in 1910 and second in 1911. When Moran signed with them they were in sixth place.

Nine rookie pitchers were being evaluated for tenure with the Tigers in 1912. At that time the active major-league roster limit was 17. It was to increase to 25 in 1914, and the Tigers planned to bring these youngsters in piecemeal within the 17-man limit, observe and evaluate them, and move them out to make room for more hopefuls.

Moran reported to the Tigers soon after school was out. On July 23 the team was in St. Louis to play the Browns, one of only two teams against which the Tigers had a winning season in 1912. (The other was the New York Highlanders.) Ralph Works started the game for Detroit and after five innings, with his team behind 5-4, was sent to the showers by manager Hughie Jennings. The stage was set for Harry Moran’s grand entrance to the major leagues. The first batter he faced was the opposing pitcher, George Baumgardner. The rookie walked him. The next batter, Burt Shotton, attempted a sacrifice that ended up as a foul out to third baseman, George Moriarty. On Jimmy “Pepper” Austin’s strikeout, Baumgardner stole second. Moran escaped as St. Louis first baseman George Stovall lined out to right fielder Sam Crawford.

The Tigers knotted the score in the seventh but the game did not stay tied long. Cleanup hitter Del Pratt started the home half of the seventh by ripping a liner into the gap between Davy Jones and Ty Cobb for a triple off Moran. Ed Hallinan popped out to Baldy Louden. Pratt scored on a passed ball and the game was tied again. Moran walked the next two batters. Then Paul Krichell hit a weak roller to Moriarty, who threw him out. Baumgardner walked again, loading the bases. Shotton fouled out to Del Gainer to end the inning.

Moran was pulled in the eighth inning for a pinch-hitter, Jim Delahanty, as the Tigers were in the midst of a two-run rally to take the lead. Joe Lake pitched two scoreless innings to get the win. In his first outing Moran faced 11 batters, gave up one hit and one unearned run, walked four and struck out one. It was not a spectacular performance but passable for a nervous rookie. The Tigers won the contest, 7-6.

Moran’s second appearance was that of a starter on July 6 in Chicago vs. the White Sox. He again faced 11 batters in a two-inning stint. He was roughed up a bit more than in his debut. He gave up four solid hits, one of which was a homer, and one walk, all of which produced three runs, one unearned. On offense in the top of the third, he got a single and scored. He ended the day batting 1.000. However, the Chicagoans carried the day, 10-9.

His next outing was on July 12 in Fenway Park. The Tigers were down 4-0 to the Red Sox in the first game of a twin bill. Moran was called in to start the bottom of the eighth in relief of Lake. He faced five batters, giving up two hits but no runs. The Tigers lost 4-1.

On July 16 Moran got the nod to start in front of 7,000 fans at Fenway Park. The high-flying Red Sox were in first place with a comfortable lead. In the background of every meeting of these teams was the bragging-rights rivalry between Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker, the two greatest center fielders in baseball.

The rookie was a bit wild, as he had been in other appearances. However, he kept the Red Sox scoreless in five of the eight innings in which he faced them. In the second inning, he should have retired the side with one hit and no runs, but miscues by Cobb, Donie Bush, and Delahanty kept the inning alive and the Red Sox collected three runs on two hits. In the third, the Beantowners cashed in on a walk and a hit to score run four, which the Tigers matched with a run in the fourth. In the seventh, Moran ran into a buzz saw. The Red Sox pounded out four solid hits – two singles, a double, and a triple – that produced three final runs. The Tigers scored a run in the ninth. The final score was 7-2, Red Sox.

In spite of the score, Moran must have been happy to pitch a complete game. For the day he gave up 10 hits, five walks, and seven runs, one of them unearned. He gave up no homers. He probably remembered to his grave that he had hit the immortal Tris Speaker with a pitch. An article in the Detroit Free Press summed up his day: “Moran was rather wild, and he started to slip towards the end of the game, but had the Tigers given him anything like half-decent support a real ball game might have developed.”4

Moran made his last appearance in a Tigers uniform in game two of a twin bill with the reigning World Series champion Philadelphia Athletics on July 19. With Tigers losing 11-2, the young lefty was called upon to relieve Ralph Works to start the sixth inning. His final appearance was another unremarkable stint. He gave up the A’s last three runs in a 14-6 rout. He faced 10 batters in 1⅔ innings, giving up three runs (one unearned), two hits, and two walks.

However, the game was quite significant. One reporter described it as “the gala day of Cobb’s life.”5 In the first game Cobb went 5-for-5 with two home runs. In the second game he tripled and singled. For the day he had two homers, a triple, four singles, six runs batted in, five runs scored, a stolen base, and 15 total bases, which at the time was a record. Only 1,500 were at Shibe Park on that noteworthy occasion.

Only two of the nine rookie hopefuls returned to the Tigers roster in 1913, George Boehler and Hooks Dauss.6

In mid-August Moran was released to the Providence Grays of the Double-A International League.7 He had no Providence statistics for 1912. Possibly he struck an agreement with the club to allow him to pass on the short remainder of the season and return to Lynchburg to study for his law degree.

He did play for the Grays, a.k.a. the Tigers castoffs, in 1913. His performance was not notable in any way. He pitched 78 innings in 17 games, struck out 37, walked 23, and ended up with a record of 2-4. The team was expected to be near the bottom of the standings before the season began and did not disappoint, finishing in sixth place.8

Baseball did not take a total backseat to Moran’s law studies. Player-manager Larry Schlafly signed him to one of first Federal League contracts, to play for Schlafly’s Buffalo team.9 Moran signed on the condition that he would not be hampered from completing his law-degree exams.

Moran arrived in Danville, Virginia, for training camp on March 30, after being held up for several hours by a freight-train wreck 20 miles north of the city.10

Spring training had been ambushed by Rex Pluviae, the rain king, forcing most of it indoors in unused tobacco warehouses, only when they were available.11 In between his studies, Moran had been helping and working out with the Washington and Lee baseball team and reported he was in better condition than he had ever been.

On April 13 Buffalo played in the first game of the 1914 major-league season. The Buffeds were visitors in Baltimore’s Terrapin Park, where nearly 28,000 spectators showed up to see the home team win, 3-2. Jack Quinn pitched a five-hitter for Baltimore. Earl Moore got the loss.

Moran made his debut and only April appearance on April 22, with a road start against the Pittsburgh Rebels. He pitched 5⅔ innings in getting the win. Russ Ford, inventor of the emery ball, pitched the rest of game for the save. The Buffeds won, 9-6. It was not an auspicious game. Moran continued to demonstrate wildness, walking five. He gave up almost two hits per inning while allowing five runs.

On May 1 Moran made his second appearance, an eight-inning relief stint. He showed more consistency than in his first appearance. He gave the Indianapolis Hoosiers two runs on six hits, issued only two passes and ended with his second win in as many appearances. He made five more appearances in May, starting three games and doing long relief in two. In the three starts he was pulled after three innings in the first game, after 5⅓ innings in the second, and after one inning in the third, losing the last two. In the two relief appearances he won one game with a five-inning stint and was not the pitcher of record in a six-inning job. He finished the month with a 3-2 record. His team, with a record of 15-16, was in third place.

On June 13 Moran pitched a six-hit shutout, beating the St. Louis Terriers, 10-0. He walked only one Terrier and struck out a career-high seven batsmen. Over the rest of the month, he got a win in long relief, lost a start, and pitched a four-inning relief stint without a decision.

August was a stellar month for Moran. He had four starts, three of which were complete games, with a record of 3-1 and one save. Down the stretch he made eight appearances, two of them relief ventures in tie games. He made four starts, going 2-2. One of the wins was a one-hit shutout with two walks and seven strikeouts.

Moran certainly made a positive contribution to his team’s success. Buffalo spent most of its time in fifth place but made a surge to fourth in September, and stayed there for the balance of the season, finishing seven games out with a .530 winning percentage. The only meaningful pennant run was between the Indianapolis Hoosiers and the Chicago Whales, with the former winning by 1½ games.

The Buffeds used a five-man starting rotation, including one left-hander, Al Schultz. Five others plus Moran were considered the relief corps. However, he got a fair share of starting duty with 97⅔ innings, 63 percent of his output. He led the relief corps with 56⅓ innings pitched, 40 percent of the team’s relief innings.

Moran ended the season with a record of 10-7, a better percentage than his team’s performance. His ERA was 4.27, compared with a league average of 3.20. He pitched in 34 games, starting 16. He threw seven complete games, two of which were shutouts. He struck out 73 batters, walked 53, and hit 11.

The spring of 1915 was filled with turmoil for the Federal League brass. Only two weeks before Opening Day it was not certain what team was going to Newark, Kansas City, or Indianapolis. However, all the while manager Bill Phillips was busily working on building his Hoofed roster for the coming season. One asset he was seeking was greater pitching strength. He negotiated a deal with Buffalo for the purchase of Moran’s contract.12 Part of the payment to Buffalo was the services of a young hurler named Roy “Rube” Marshall, who represented the final payment for Moran.13 Once the deal was done, Phillips spent several days negotiating with Moran to get him to sign, an achievement that was announced on March 4. It was believed that Moran, under Phillips’s patient tutelage, would “develop into a first-class hurler and prove of great aid to the Hoofeds.”14 Phillips had only three weeks to prepare Moran for his hoped-for destiny.

The team left for spring training in Valdosta, Georgia, on March 6 as the Indianapolis Hoosiers. While the Hoofeds were trying to coalesce as a professional baseball unit, their fate was being determined by deliberations involving the federal courts, the Indianapolis stockholders, the Federal League brass, and potential buyers, i.e., Harry Sinclair and J.T. Powers. Also involved in the negotiations was the financial survival of the Kansas City Packers. Both the Hoofeds and Packers were potentials to be moved to Newark, New Jersey.

On March 23 the Indianapolis stockholders agreed to assign ownership and debts of the franchise to the Federal League.15 The Packers came up with a financial plan acceptable to the court to pay its debts and keep the team in Kansas City, based on subscriptions from backers.16 However, Harry Sinclair had already contracted to purchase the Packers so was now out of a ballclub. The league awarded him ownership of the Indianapolis club, which he moved to Newark with a new name, the Peppers.

Moran’s season debut came on April 14 vs. the Brooklyn Tip Tops. Evidence of wildness continued to shadow him. He pitched a complete game, losing 8-7, while giving up 11 hits, walking six, and hitting a batsman. Three of the seven runs were unearned. The Peppers defense was found wanting with four errors, two of them by Moran. He redeemed himself for the balance of the month with two complete-game wins, one a two-hit shutout. He also had a relief stint.

In May Moran had four starts (three complete-game wins and a loss), bringing his record to 5-2. He was 2-3 in June with two complete games. In July he had two relief stints and made four starts, three of them complete games. He won two and lost two. By the end of the month he was 9-7, had brought his walk count down and sported a 2.90 ERA.

August was a red-letter month for Moran. He picked up three wins and no losses in a relief stint and three starts, one of which was a five-hit shutout. He pitched seven innings in a start for which he was not the pitcher of record. He yielded only three runs in the month. His record was 12-7. The stage was set for the stretch run. The Peppers were only 1½ games behind the first-place Pittsburgh Rebels.

Moran had 11 days’ rest between his last August appearance and his September 3 appearance in a relief role. After what must have seemed a buoyant season up to this point, his stretch-run performance turned into a depressing series of events. He made 11 appearances, only three of which resulted in a win for the Peppers. He picked up his only win in relief. He lost two of four starts. (He was not the pitcher of record in the other two.) Moran and George Kaiserling shared space in the same pitching game summary seven times during the run.

The game of September 24 against the Pittsburgh Rebels had to be the contest most indelibly stamped into Moran’s memory for the rest of his days. In the bottom of the third, with the game hitless and scoreless, things got a little shaky. Steve Yerkes, led off with a single to left. Paddy O’Connor hit a grounder to Moran who threw to second. However, Jimmy Esmond dropped Moran’s throw. Clint Rogge forced Yerkes at third, Moran to Ted Reed. Marty Berghammer forced Rogge at second, first baseman Frank LaPorte to Esmond, while O’Connor took third. Berghammer stole second when Esmond dropped the ball for a second time. Moran intentionally walked Cy Rheam to get at the left-handed-hitting Rebel Oakes. The tactic worked. LaPorte threw out Oakes. No damage.

In the fourth, Esmond redeemed himself by driving in the Peppers’ only run of the day. In the bottom of the ninth, with the Peppers leading 1-0 and two outs, the Rebels eked out a run when Jim Kelly reached on an error by second baseman LaPorte and scored the tying run on Yerkes’ smash, on which Esmond turned a somersault attempting to stop it.

In the 10th the Peppers failed to score. Walt Dickson singled to center. Bill McKechnie17 decided to replace Moran on the hill with Kaiserling. Moran refused to accept the substitution. McKechnie had to take the ball out of Moran’s hands so the game could continue. Jack Lewis forced Dickson at second and eventually scored on a throwing error by LaPorte for a 2-1 victory. Moran allowed no earned runs but still lost the error-plagued contest.18 The emotionally charged performance was his last professional start.

On October 3 Moran was a reliever in his final professional baseball game, pitching 3⅓ innings in relief of Kaiserling in a loss to the Baltimore Terrapins.

After all the smoke cleared, the Newark Peppers were nestled in fifth place but only six games out in arguably the tightest pennant finish in history. The top five were all over .500. Only .001 separated the top two teams.

The 1915 season had truly been truly the high-water mark for Moran’s professional career. He showed notable improvement over 1914. He went from being a somewhat marginal pitcher with a penchant for wildness to a consistent starter with more savvy and traces of wildness, as he led the league in hit batsman with 18. He had career bests in games won (13), winning percentage (.591) ERA (2.54), starts (23), complete games (13), innings pitched (205⅔), and WHIP (1.259). He was stingy with the home-run ball, giving up only two. His ERA and WHIP were both below the league average for the year.

In 1916 Moran appeared on the rosters of the Double-A American Association’s Louisville Colonels and Milwaukee Brewers. However, no statistics exist to indicate that he actually played with either team. Therefore, 1915 closed the door on his playing career.

Life did go on handsomely for Harry Moran after baseball.

On May 8, 1918, he enlisted in the US Naval Reserve Force and went on active duty stint as a seaman on July 15. He mustered out of active duty on December 14, 1918, and was honorably discharged on September 30, 1921. In 1917 he was presented a lifetime pass to Detroit Tigers games. He carried it with him when he went on active duty. He encountered a young flier who wanted to see a Tigers game. Moran loaned his card to him. While he was in the stands watching the game, the pilot was called to duty immediately, with no time to return the pass. Twenty-six years later, at a chance meeting of Washington and Lee alumni in St. Louis, a high-ranking naval officer returned the card to its owner.19

In Manhattan, Moran married Mabel Anderson on December 30, 1919. They had a daughter, Joan, who was born about 1925. Joan married in Raleigh, West Virginia, in 1949, and the couple settled in North Carolina.

Harry Moran had many assets for success. He was tall and athletic, inherited a family history of determination, had a law degree, was accustomed to leadership roles, and enjoyed strong ties with the coal industry. He took advantage of those assets to become a coal magnate. He purchased and/or operated coal properties, primarily in New York and West Virginia.

Moran lived in New York before returning to his West Virginia hometown in 1940. While living in the East he was president of the Lake and Export Coal Corporation; executive vice president-treasurer of the Northeast Coal and Dock Company in Bucksport, Maine; and vice president and treasurer of the Maine Coal Sales Co. in Bangor, Maine. He relinquished active control of these enterprises when he came to Beckley to take control of Leccony Smokeless Fuel Company. He was glowingly proud of the feat his company performed in 1943, driving a 1.25-mile tunnel through a mountain near Bosoco, West Virginia, to reach an 1,800-acre tract of untapped coal.

Harry’s wife, Mabelle Andeson Moran, remained in New York city with her mother and sister, who attended to her during a lingering illness. She died on September 30, 1942. Her remains were transported to Huntington, West Virginia, where she was interred after rites were conducted. The couple’s daughter, Joan, was attending school at Mary Baldwin college.20

Moran was also a prominent and active citizen of Fayette County. He held offices in several community organizations. He was a member of the Methodist Temple. After returning to Beckley he married Fonda Lee Morrison, formerly of Greenbriar, West Virginia. They had two daughters.

Moran died on November 28, 1962, in Beckley, West Virginia, at the age of 73 for reasons unreported. He was survived by his wife, three daughters, and four grandchildren. He was buried in High Lawn Memorial Park in Oak Hill, West Virginia.21

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, SABR.org, Baseball-almanac.com, and the following:

Wiggins, Robert Peyton. The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs: The History of an Outlaw Major League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008).

Notes

1 LD’s surname was Morane on the 1900 Census but changed to Moran on the 1910 and later censuses.

2 The fact that Moran attended Fishburne was obtained from his 1914 Washington and Lee yearbook via ancestry.com. Information about the school is from google.com/search?q=fishburne+military+school&oq=&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

3 Cited in the 1912 W&L Yearbook via ancestry.com.

4 “Tigers Lose Final Game,” Detroit Free Press, July 17, 1912.

5 “Cobb’s Wonderful Batting Enables Tigers to Split,” Detroit Free Press, July 20, 1912.

6 Boehler lasted four more years with the Tigers and five with four other teams. In nine seasons he had a career record of 6-12 and 202⅓ innings pitched. Dauss remained a Tiger his entire 15-year career, pitching 3,390⅓ innings with a 223-182 record.

7 “Moran Goes to the Grays,” Detroit Free Press, August 15, 1912.

8 “Rochester Writer Picks the Herd,” Buffalo Times, March 29, 1913.

9 “Indoor Practice Is Again on Bill,” Buffalo Enquirer, March 31, 1914.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 “Former Philly to Be Hoofed,” Indianapolis Star, March 4, 1915.

13 “Marshall Is Ninth Twirler on Blues’ List,” Buffalo Evening News, March 29, 1915.

14 “Former Philly.”

15 “Hoofed Club Votes to Give Up Franchise,” Buffalo Evening News, March 24, 1915.

16 “Federal League Club Stays in Kansas City,” Atlanta Constitution, March 24, 1915.

17 Phillips had been fired as manager in June.

18 The play-by-play comes from “Rebels Tie and Win on Pair of Errors by LaPorte, 2 to 1,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, September 25, 1915.

19 “Harry E. Moran,” Raleigh Register (Beckley, West Virginia), November 29, 1962.

20 “Wife of Coal Operator Dies,” Raleigh Register, October 1, 1942.

21 “Moran Rites Are Today,” Beckley Post Herald, November 30, 1962.

Full Name

Harry Edwin Moran

Born

April 2, 1889 at Slater, WV (USA)

Died

November 28, 1962 at Beckley, WV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.