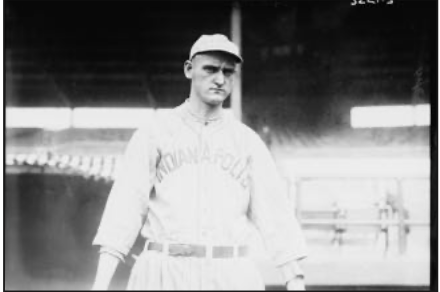

George Kaiserling

George Kaiserling was born to a German immigrant couple, Frederick and Johanna (Becker) Kaiserling, on May 12, 1893, in Steubenville, Ohio. He was the sixth born of eight, six sons and two daughters. His father worked as a millhand in the basic steelmaking industry and his mother was a homemaker.1

George Kaiserling was born to a German immigrant couple, Frederick and Johanna (Becker) Kaiserling, on May 12, 1893, in Steubenville, Ohio. He was the sixth born of eight, six sons and two daughters. His father worked as a millhand in the basic steelmaking industry and his mother was a homemaker.1

There is only data from the 1910 census to connect his timeline from birth to his initial season in professional baseball. From that census we know he was still living at home and unmarried. Three of his siblings had already left the roost. When he wasn’t playing baseball, he was a glassworker, as were two of his siblings.

In 1910, at the age of 17, Kaiserling played his first season of professional ball with the Great Bend Millers of the Class-D eight-team Kansas State League. He was 5.8 years younger than the average pitcher in the league. In spite of his youth he acquitted himself well, playing in 30 games and posting a record of 12-12. The Millers ended in fourth place with a 55-55 record, 16½ games off the pace.2

In 1911 Kaiserling split his time between two Class-D Illinois-Missouri League teams, the Clinton Champs and the Lincoln Abes, both in Illinois. The Champs were the league champions; the Abes finished fifth of six. Kaiserling’s records for the season are incomplete but the best estimate is that he posted a 24-4 record, throwing 200 innings.

Advancing to Class-B ball in 1912, Kaiserling plied his trade with the South Bend Benders of the 12-team Central League.3 At 19, he was almost seven years below the average age of all the hurlers in the league.

When Kaiserling first reported to the team and observed that he was vying with a dozen hurlers for a roster spot, he lost confidence and asked to be released to Champaign of the Illinois-Missouri League. The local team ownership vetoed his request and demanded that he get out there and show them his talent. Still lacking confidence, he faltered whenever he made an appearance.

His player-manager, Harry Arndt, a South Bend native, had spent four seasons in the major leagues, playing his last game on May 25, 1907, with the St. Louis Cardinals. Arndt felt positive about Kaiserling’s latent ability and made arrangements to option him to Muskegon of the Michigan State League. He ordered the young pitcher to report to his new team.4Arndt and the team went on an extended and disastrous road trip. In the team’s absence, Kaiserling refused to report to Muskegon, risking suspension. When the team returned on May 14, he prevailed with Arndt to give him another chance. The latter agreed and, as it turned out, was well rewarded for his decision.

Kaiserling, a.k.a., the king of the spitball,5 pitched in 29 games, hurled 220 innings, gave up 4.75 total runs per nine innings pitched and compiled a record of 11-16 (.407). His WHIP was 1.314. He swung the bat and fielded well. He hit the only home run of his professional career. The blow at the time was the longest ever hit in the Zanesville, Ohio, ballyard.6 The Benders ended the season with a lackluster 41-88 (.318) record, the worst in their five-year history. In spite of South Bend’s poor showing, fans and the local press considered “Der Kaiser” a solid star of the league.7 Perhaps they saw in him what the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association saw, considering that the Indians bought his contract after the season.

The Indianapolis franchise was in the throes of a major transition. The fans wanted somebody’s head. The team won the Double-A championship in 1908 but spiraled to the cellar by 1912, losing 111 games. For a team that had won the inaugural championship of the league in 1902, last place was not conceivable. In response to fanbase discontent, owner Sol Meyer, a banker, took remedial action. For the 1913 season, he decided to find a new manager with a proven track record.

Meyer’s choice was Mike Kelley, manager of the league rival St. Paul Apostles. During his 8½ years at the helm, Kelley had not only kept a club with sparse resources respectable, he led it to two league championships. The Indianapolis fans and sportswriters were ecstatic over the prospects for their prized Indians. With a proven talent at the helm and an owner with deep pockets, they could envision the promised land on the horizon.

Big George Kaiserling was a strapping lad at 6-feet and 175 pounds. His mien was beyond his years. He threw and batted right-handed. He was strong and powerful. In spite of his physical assets, he still needed to perfect his pitching skills and adhere to a rigid conditioning regimen if he wanted to advance to the majors.

The 1913 season started off better than expected. Unless a Double-A team has a cadre of veterans returning, the first month of the campaign can be tenuous until the major-league teams cut their rosters to 25 players on May 1. The scramble then begins to land players for the run for the pennant. Kelley did a good job of keeping his team viable for the month of April. He had only four conditioned hurlers, Kaiserling, Otto Merz, Bill Schardt, and William Harrington, but managed to stay no worse than second by the end of April.

However, the wheels started coming off in May. The pitching corps became erratic and the outfield was notoriously error-prone. Kaiserling was inconsistent. One game he threw a two-hitter, after which he had the audacity to ask for a raise. In his next start he lasted only one inning, surrendering six runs, on four hits and a walk, before the first out. By the end of May the Indians had plummeted to seventh and tallied the worst fielding percentage in the league.

Kelley was desperate and the 20-year-old Kaiserling was problematic. He lacked focus on keeping in shape and learning the finer art of pitching. Perhaps Kaiserling’s German culture clashed with Kelley’s Irish, both being first-generation Americans. At any rate, Kelley announced to the press on July 26 that Kaiserling had been sold to the San Francisco Seals of the Double-A Pacific Coast League to make room for George Norton, a southpaw from Hastings of the Nebraska State League, who was expected to arrive on August 15.8

At his departure Kaiserling had worked 109 innings in 27 games, compiling a record of 5-7. He had a WHIP of 1.459. In comparison, the average major league WHIP in 1913 was 1.285. Was Kaiserling major-league material?

It so happened that there was another team in town, the Indianapolis Hoosiers of the six-team, independent Federal League. The manager, who had been let go in the offseason by the Youngstown Central League team, was Bill Phillips, whom the Indianapolis press often referred to as “Whoa Bill” or “Silver Bill.”9 His team was leading the pack and Phillips intended to retain the lead. Phillips had managed Youngstown in the Central League in 1912 and saw Kaiserling pitch for its South Bend rival. He certainly must have noted his potential and decided he could round out his pitching corps. Kaiserling did not want to play on the West Coast and opted to throw in his lot with the Hoosiers. In the process he became a Federal League “jumper.”

Manager Phillips gave Kaiserling his first start on August 5 vs. the Cleveland Green Sox. The visitors roughed him up, scoring four runs on six hits, including two triples. Kaiserling, in eight innings of work, struck out three, walked four, and dished out a wild pitch. It was an inauspicious start but nothing that chagrined Phillips. He kept Kaiserling in the rotation and his confidence was rewarded. Kaiserling began to demonstrate consistency, reliability, and winning.

Phillips noted that Kaiserling had mastered two pitching assets he could throw with respectability, the knuckleball and the spitter.10 He may not have been as proficient as the respective creators of those pitches, Eddie Summers and Frank Corridon, but he could fool many a batter with them. Phillips noted that Kaiserling still had to learn to hold runners on base more effectively and throw to the hitters’ weaknesses, but he had every confidence his new addition would achieve those improvements over time.

On August 17 Kaiserling pitched a four-hitter against the St. Louis Terriers, winning 4-1. He hit a triple to help his own cause. He walked four and struck out three. On August 27 he pitched another four-hitter and won 3-1 over Pittsburgh. He faced the Terriers again on September 6, winning 10-4. His performance was not crisp, but he did pitch a complete game, scattering nine hits, albeit walking six. He got another triple off St. Louis pitching.

The pennant-winning Hoosiers’ regular season came to an end on September 14 with a doubleheader sweep of the St. Louis Terriers. Kaiserling pitched brilliantly in the opener, coming out on the long end of a 9-2 score in a short-duration game. The Hoosiers finished with a commanding 10-game margin over second-place Cleveland.

Since there was no opposing team to play in a World Series, it was decided that the Hoosiers would play an all-star team from the remaining five entrants. The gate receipts would go to the players. It was to be a best-of-five series. Because of wet field conditions, the opening game, scheduled for September 17, was postponed day-by-day until the 21st. It was then decided to reduce the series to best of three, starting with a doubleheader on September 22. The games would be just seven innings long, since threatening weather was forecast.

Phillips, himself the possessor of a long and successful pitching career, had worked wonders with Kaiserling, who performed well in the stretch. There was a chemistry between the two that was totally absent with Kelley. Phillips was notably reserved in his approach to managing. It was no surprise when he selected Kaiserling to start the first game of the all-star twin bill.

Kaiserling dominated the All-Stars in the first contest, pitching a 2-0 shutout. He allowed just four hits, walked none, and struck out three. His defense played errorless ball behind him and choked off a scoring threat in the sixth with a double play. Kaiserling singled and scored a run to aid his own cause. As he was on a roll, Phillips let him start the second game. Not only did he start, he finished it, pitching shutout ball through the sixth inning. He was determined to get back-to-back shutouts, but had a lapse in the final inning, allowing three consecutive hits that resulted in one run. The Hoosiers won, 4-1, and were the league champions.

Phillips took all but three of his players on a barnstorming tour across Ohio and into western Pennsylvania through September 30. Some of the games were played in team members’ hometowns.11

The Federal League of 1913 was founded by J.T. Powers purely as an independent league. It had no affiliation with the major leagues and operated outside Organized Baseball’s 1903 National Agreement. Much to the chagrin of his owners, Powers did not declare the league one in competition with the major leagues. Still, the National Commission viewed it as an outlaw league. The major leagues put pressure on Western Union, which had a virtual monopoly over data traffic in the United States, to not contract with the Federal League to deliver its data. Western Union complied, and the Federal League’s data could not be consolidated and maintained. As a result, there is a lack of reliable statistics for the six franchises and the author is unable to render a statistical testimony to Kaiserling’s performance with the Hoosiers of 1913.

For 21-year-old Kaiserling, 1914 was a stellar year. He had good chemistry with his manager, who primed his pump with a positive report to the press about his expectations for the pitcher in the coming season. Kaiserling had established familiar rapport with the Hoosiers fans and obeyed Phillips’ instructions to follow a rigid conditioning program during the offseason. He was ready to produce.

In spite of his youth, Kaiserling was a mainstay in a starting rotation that acquitted itself brilliantly in 1914, most notably in the latter half of the season. An addition to the staff was a 34-year-old veteran of nine major-league seasons, Cy Falkenberg. He was coming off a five-year hitch with the Cleveland Naps, interrupted in 1912 for a season with Toledo of the American Association. During this season Falkenberg perfected a new pitch, the emery ball. With the new weapon in his arsenal in 1913 he had his career-best major-league season, compiling a 23-10 record along with a respectable ERA of 2.22 and a WHIP of 1.181. His meteoric rise from mediocracy to stardom was attributable to his mastery of his new pitch. The new president of the Federal League, James A. Gilmore, personally lured Falkenberg to the Federal League with a three-year, $15,000 contract.

A second addition to the mound corps was Earl Moseley, a 26-year-old right-hander whose only major-league experience was with the Boston Red Sox in 1913. In 1912 he had pitched for Bill Phillips at Youngstown of the Class-B Central League. He had been 8-5 with the Red Sox. A third addition was right-hander George Mullin, a 12-year major-league veteran and former Detroit Tigers star. At age 33, he had fallen off the shelf the past two seasons. He came to Indianapoliswith a 212-184 lifetime record. His hallmark year was 1909, when he led the major leagues in wins and the AL in winning percentage with a 29-8 mark (.784). Eight other hurlers essentially rounded out the relief staff.

In spite of Phillips’ optimism, the season did not start as he advertised. On June 10 the Hoosiers were languishing in seventh place. Kaiserling was in the doldrums with a 1-1 record. On the 11th he took the mound for game one of a twin bill vs. the league-leading Baltimore Terrapins. He did not finish but did get the win in a 6-5 contest. Falkenberg got the save. As inauspicious as the game may have seemed at the time, it was the first of a 15-game winning streak that vaulted the Hoosiers into first place. When the skein was broken on June 25, Kaiserling’s record was 5-1. He did not seem flush with self-motivation but thrived on the momentum of the cresting wave.

Kaiserling was pumped. On July 19 he threw a one-hitter. Heading into August, the Hoosiers had dropped to third. By August 31 they were in a first-place tie with Chicago. The September run for the pennant was a hard-fought, day-by-day struggle with the Chi-Feds of Joe Tinker. On September 1 George was 14-6. During the stretch run he went 3-3. On October 5 the Chi-Feds had the lead. The next day the Hoosiers grabbed it and held on to the last day, October 8, winning the pennant by 1½ games.

Kaiserling’s 17 wins were a career high and the 11th best in the Federal League. (He lost 10 games.) His winning percentage of .630 was a personal best, and was well above his team’s winning percentage of .575. Falkenberg with 25 wins and Moseley with 19 topped Kaiserling on the Hoosiers staff. His ERA of 3.11 was a tad under the league ERA average of .320 but over the major-league average of 2.91. His WHIP of 1.308 was on par with the league average of 1.301. Kaiserling pitched a career-high 275⅓ innings in 37 games. He led the league with 17 hit batsmen. The Washington Times commented wryly: “When looking for gunners how did Wilhelm of Germany miss Kaiserling of the Hoosiers, who hit 17 batters last season.”12

The Hoosiers managed to win in spite of being next to last in fielding. However, three players did shine on defense. Kaiserling played two-error defense all year and shared honors with George LeClair of Pittsburgh. Charlie Carr led the field among first basemen. Edd Roush was one of six outfielders to make only one error in the season.

After the season the Hoosiers were disbanded amid complex financial issues. Harry Sinclair, one of the team’s owners, bought out his peers and moved the team east. His intent was to plant it in New York City, but the Yankees and Giants opposed the move. The closest Sinclair could get was Newark, New Jersey. He named the new team the Peppers, typically shortened to the Peps.

Kaiserling held out for more money during the offseason.13 He came to terms on December 14, well before March 6, when the team was scheduled to leave for spring training in Valdosta, Georgia. The Indianapolis press corps covering training camp reported it interviewed several players, including Kaiserling, who noted they had taken excellent care of themselves during the offseason.14 Early in camp the press noted that Kaiserling had “rounded to form faster than the other hurlers….”15

As a testament to Kaiserling’s favor with the fans he was included in a cast of major-league players in the 1915 edition of the Cracker Jack baseball card set. He was number 157 out of a cast of 176.

The Peppers were essentially the same team as were the Hoosiers of 1914, except for one significant difference. The previous year’s league-leading offensive dynamo, Benny Kauff, was no longer on the roster. He had been purchased on an option held by the Brooklyn Tip Tops from the Indianapolis franchise the previous fall.16 “The Ty Cobb of the Federal League,” as the press anointed Kauff, was a painful loss. The addition of Harry Moran and Cubs veteran Ed Reulbach on paper should have provided more pitching strength. First baseman Charlie Carr, the 38-year-old comeback player of 1914, decided to retire as a player. Phillips replaced him with Emil Huhn, a 23-year-old rookie, who was not the offensive equal of Carr.

Kaiserling won all three of his appearances in April. His season start was just the opposite of 1914. The 1915 season opened on April 10 and Kaiserling took the hill for the first time on April 12. He pitched a complete game in an 8-5 win over Baltimore, and hit a double. A week later he beat Baltimore again, 13-2. He had two singles and drove in two runs. On April 25 he engaged in a 14-inning pitching duel with Buffalo that netted him a 2-1 win in spite of three errors by his defense. He drove in a run with a sacrifice fly. The Peppers were leading the league by a half-game.

With a record of 1-3, May was nearly a reversal of April. Kaiserling’s one victory was an 8-0 shutout of Pittsburgh. During the same span the Peppers dropped to fourth but were only two games off the pace.

In June Kaiserling pitched in eight games, winning three, losing two and saving one. The other two were in relief. In one win he hit a sacrifice fly to drive in a run. The team dropped to fifth place at 33-33, but only six games behind the first-place Kansas City Packers.

By the end of August, the Peppers had captured second place, trailing the league-leading Pittsburgh Rebels by 1½ games. Kaiserling was a tireless workhorse for the Peps in the stretch run, making 15 appearances and pitching 68 innings. Through August he had made only 26 appearances, and averaged only 38⅔ innings per month. Two of his stretch appearances resulted in ties and negated 13 innings of his work. One went nine innings before darkness closed it down. Aside from that endeavor he started six other times, ending up with two wins and four losses. He picked up avictory in relief. He was brought in as a reliever seven times, not including a tie game, getting one save. On September 5 he pitched in relief in each game of a twin bill. He pitched three complete games, besides the tie, one of which was a two-hit shutout. Kaiserling was a real iron man down the stretch, taking the mound four times with no days’ rest.

In spite of all his efforts Kaiserling did not get the team any closer to taking the lead in the pennant chase. At the end, the Peppers were in fifth place but only six games behind the pennant-winning Chicago Whales, who beat out the St. Louis Terriers by just .001. It has to be the closest pennant chase in history. The Pittsburgh Rebels were only .003 behind the Terriers.

Kaiserling ended the season 15-15, tied with Moseley with the same record, for second best on the staff. Ex-Cub Reulbach led the pitchers with a 21-10 record. Cy Falkenberg, who had such a terrific 1914 season, dropped to 9-11. In the offseason Harry Moran had been obtained from the Buffalo Feds and contributed a record of 13-9 to the cause.

In some categories Kaiserling had personal bests: games (41), ERA (2.24), shutouts (5), runs allowed per 9 innings, (3.10), WHIP (1.221), and home runs allowed (1).

Kaiserling was officially out of a job on December 22, 1915, when the unprofitable war between Organized Baseball and the Federal League ended. Kaiserling was among the players on six teams who could be sold to the highest bidder under the deal that shut down the Federal League. No major-league team made a bid for him. Kaiserling was back home in Steubenville, likely working in the glass industry. He was among 89 Federal League players who never played for a major-league team before or after their Federal League service.

The Indianapolis Star reported on February 15, 1916, that Kaiserling might have returned in an Indianapolis Indians uniform if he agreed to terms.17 He was thought to be Indians baseball property. On March 2 the Indianapolis Newssaid that Kaiserling had been purchased by and was to report to the Detroit Tigers.18 On March 7 Roger Bresnahan, owner of the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association, said he had purchased Kaiserling.19 On March 17, a newspaper quoted Hughie Jennings, manager of the Tigers, as indicating that if the Tigers had acquired Kaiserling, he had no part in the deal.20 On March 26 another would-be owner of Kaiserling’s contract was President Jason Draper of the International League Providence Grays, who contended that he had purchased it from Powers of the Newark team. Edward Barrow, president of the International League, intervened to stop the deal. He would allow no “outlaw” players in his league, the only league president to mandate such action.

On March 19 Kaiserling reported to Dawson Springs, Kentucky, for spring training with Toledo. That answered the question of whom Kaiserling would play for. In spite of that, the press continued for a month to write that he was playing for Detroit.21

The Mud Hens were returning to Toledo after a two-year absence. Club owner Charles Somers, who also owned the Cleveland Indians, had moved the Mud Hens to Cleveland in 1914 to keep the Federal League from locating a rival team there.

On April 18, 1916, Toledo welcomed its team back in grand style. “Beginning with an automobile parade at 10:30 A.M., in which thousands of motorists participated, the city, by order of Mayor Charles M. Milroy was turned over to baseball.”22 Most civic offices and many businesses closed for the day to allow workers to attend the game. The battery for the first pitch was National League President John K. Tener pitching and Mayor Milroy catching. An overflow crowd of 18,000 jammed the 11,800-seat ballpark in fine weather.

Hugh Bedient, picked up from the defunct Buffalo Federal League team, got the nod to start the opener against the Milwaukee Brewers. The Toledo team, which had been renamed the Iron Men, won the game, 4-2. The next day Kaiserling scattered four hits and the Iron Men won for the second time in two days, 3-1.

In spite of the season’s exciting start the Iron Men started a descent that took them into the second division. Kaiserling took the mound for his last turn of the season on September 30 in Louisville, whose squad had won the league title. Kaiserling got an easy 9-2 win. He finished the season and his career on a positive note. The next day, the last of the season, the Colonels and the Iron Men split a twin bill by 2-1 scores. Toledo wound up in sixth place with a .476 percentage.

Kaiserling finished the season with rather pedestrian numbers. He pitched in 36 games, won 10, lost 13 (.435), threw 240 innings and had a WHIP of 1.313.

The author has little but fragmentary information about Kaiserling for the balance of his life. He returned to Steubenville and presumably worked again in the glass industry. On his World War I draft registration card, he stated that he was married. No name for the spouse was requested. No marriage record is to be found.

Kaiserling’s death notice in the Steubenville newspapers said he was a pitcher for Memphis of the Southern League. Baseball-Reference.com suggests that the team was the Chattanooga Lookouts. In either case he did not play in 1917 because he had contracted tuberculosis. He died on March 2, 1918, at the age of 24.

One cannot know how much Kaiserling’s German heritage may have affected his game or his appeal to the major leagues. As America’s entrance into World War I approached, he might have been a target of nationalism. One item that suggests something along those lines: “Montreal denies that it is after Twirler Kaiserling, of Toledo. ‘We wouldn’t take a pitcher with a name like that for twenty cents,’ wrote the Montreal manager. ‘We can’t use Kaisers or Kaiserlings up here.’”23

The best two years Kaiserling had were with the Federal League. After its collapse, no major-league team showed interest in obtaining him, in spite of his youth and physical condition. He seemed to thrive under the tutelage of the mild-mannered Bill Phillips and in the charged atmosphere of the 1914 pennant chase. He had problems with fiery Mike Kelley and possibly Roger Bresnahan. History has left us little to go on.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org,SABR.org, Baseball-Almanac.com, and the following:

Wiggins, Robert Peyton. The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs: The History of an Outlaw Major League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008).

statscrew.com/minorbaseball/roster/t-ii12156/y-1913

Notes

1 Workers in the basic steelmaking industry make the product from scratch, bringing together iron ore, a fluxing agent (like limestone), and a carbon source (like coke) with high heat. The molten product is called steel. The liquid steel is poured into an ingot mold until it solidifies. Heating it up again allows the ingot to be rolled into a shape either for a bar or sheet product.

2 baseball-reference.com/register/league.cgi?id=1709a13e.

3 Although Benders was the official team name, the press never used that term. It described the team as the Greenstockings, Green Sox, or Greens.

4 “GreenSox Return from Long Jaunt,” South Bend (Indiana) Tribune, May 21, 1912.

5 “Muse-ettes,” South Bend Tribune, September 21, 1912.

6 “Pair of Greens to Rise in Baseball,” South Bend Tribune, June 4, 1912.

7 “Muse-ettes,” South Bend Tribune, August 9, 1912.

8 “Kaiserling Goes to Frisco,” Pittsburgh Press, July 26, 1913.

9 Ralston Goss, “Bill Phillips Lectures Men on Team Play,” Indianapolis Star, March 31, 1914.

10 Ibid.

11 “Hoosiers to Barnstorm,” Indianapolis Star, September 21, 1913.

12 “Here Are Some Baseball Jots Gathered from Everywhere,” Washington Times, December 31, 1914.

13 “Bradley May Succeed Carr at Indianapolis,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 5, 1914.

14 “More Hoofeds Get In,” Indianapolis Star, March 6, 1916.

15 “Hoosier Practice Held Up by Pranks of Wind,” Indianapolis News, March 17, 1916.

16 “Ben Kauff and Cy Falkenberg Secured for the Tip Tops,” Brooklyn Times, March 25, 1915.

17 “Indians Shaping up as Pennant Contenders,” Indianapolis Star, February 15, 1916.

18 “Kaiserling Goes Up,” Indianapolis News, March 2, 1916.

19 “Pitcher Kaiserling is Signed by Toledo Club,” Richmond Times, March 26, 1916.

20 “Jennings Denies he Has Kaiserling,” Washington Times, March 30, 1916.

21 “Sporting Notes,” Battleboro Reformer, April 8, 1916; “The Week of the Big Show,” Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer, April 10, 1916.

22 “Toledo Fans Wild,” Dayton Daily News, April 18, 1916.

23 “Jabs and Stab,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) Herald, May 2, 1916.

Full Name

George Kaiserling

Born

May 12, 1893 at Steubenville, OH (USA)

Died

March 2, 1918 at Steubenville, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.