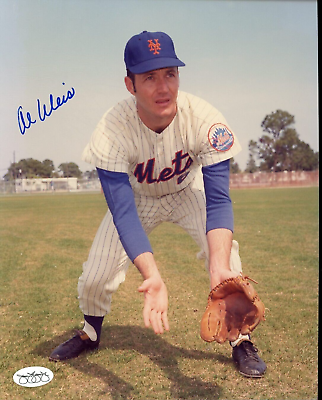

Al Weis

“There is a tide in the affairs of men. Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune; Omitted, all the voyage of their life is bound in shallows and in miseries,” wrote William Shakespeare in Julius Caesar. The line, spoken by Brutus, might well have been spoken about Al Weis. The self-described “journeyman ballplayer” took the tide at the flood and became a hero of one of the most fabled World Series championship teams of all time.

“There is a tide in the affairs of men. Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune; Omitted, all the voyage of their life is bound in shallows and in miseries,” wrote William Shakespeare in Julius Caesar. The line, spoken by Brutus, might well have been spoken about Al Weis. The self-described “journeyman ballplayer” took the tide at the flood and became a hero of one of the most fabled World Series championship teams of all time.

Albert John Weis was born on April 2, 1938, in Franklin Square, New York, and grew up in Bethpage, graduating from Farmingdale High School. He joined the Navy at the age of 17 and played for the baseball team in at the Norfolk Navy base. There, the Chicago White Sox offered him a contract.

Twenty-one-year-old Al Weis—known to his teammates as Weasel—broke into pro baseball with Holdrege of the Class D Nebraska State League in 1959, batting .275 in 62 games in the short-season circuit. Over the next three seasons, he progressed through the minor leagues: 1960 in Lincoln (Three-I League, Class B), 1961 in Charleston (South Atlantic League, Class A), and 1962 in Indianapolis (American Association, Triple A). For Indy he slapped 13 triples and batted .296. During his four-year apprenticeship, he hit .266, with 15 home runs.

The White Sox called up the 24-year-old switch-hitter at the end of the 1962 season. He had 12 at-bats and got his first hit but mainly soaked up the atmosphere playing behind the double-play combo of Luis Aparicio and Nellie Fox. At season’s end, Aparicio was traded to Baltimore in a six-player deal that brought back Ron Hansen, who had a stranglehold on Chicago’s shortstop for the next three seasons.

In 1963, Weis backed up Fox and Hansen, also filling in once at third base. During his career, the thin switch-hitter with the de rigueur early 1960s crew cut demonstrated his utility bona fides by playing 488 games at second and 204 at short. (He also filled in nine times at third and played four games in center field.) Appearing in 99 games in his first full season in the majors, he led the team in stolen bases with 15, a category he led the club in again the next season with 22.

Though still productive, Nellie Fox was past his prime and Weis’s progress allowed the White Sox to trade Fox away at the end of 1963 and turn the second-base job over to Weis. He played in a career-high 133 games in 1964, 116 of them at second, contributing materially to the second of three consecutive Chicago second-place finishes, this time one game behind the Yankees. He followed that by hitting a career-high .296 in 1965 though his playing time at second was decreased to 74 games (103 in all) as Don Buford took over the position. Under new White Sox manager Eddie Stanky in 1966, Weis saw more action at second (96 games) as Buford was moved to third and Hansen was injured, but Weis’s offensive productivity fell off dramatically. He batted just .155 in 187 at-bats.

His hitting improved in 1967, the year of the epic American League pennant race between Boston, Detroit, Minnesota, and Chicago. His season, however, ended on June 27 when he broke his leg in a collision with Baltimore’s Frank Robinson at second base. He played in just 50 games and had only 55 plate appearances. Not surprisingly, Weis was available when the season ended.

Over in the National League, the New York Mets had endured five 10th-place finishes in their six years of existence. The Mets brought in manager Gil Hodges, who had spent the past five seasons directing the Washington Senators to five straight second-division finishes. The team had the nucleus of a good young pitching staff with Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, and Nolan Ryan, but it was in need of steady defense up the middle and would take any offense they could find as well. On December 15, 1967, the Mets sent four players to the White Sox for outfielder Tommie Agee and—in what seemed to many like an afterthought—Al Weis.

Weis, 29, had been working for the White Sox public-relations department in the offseason and was pleasantly settled with his wife, Barbara, and family in the Chicago suburb of Hillside. Arriving home from work that day, he got the call from the Mets. “My reaction was, ‘Oh, no.’ After all these years with a contending team, I was going to a last-place club,” Weis said later. “It’s the ambition of every player to play in a World Series; now I figured that was the end of that dream.” Still, he took the tide that led to fortune.

Weis was not merely a throw-in in the swap. Hodges had seen him play for the past five years and the deal with the White Sox was one of the first things he worked on after joining the Mets. The manager told Weis he would not have made the deal if the White Sox had not included him. “Things like that give you confidence,” Weis said. “All through the season he let me hit in a lot of situations where other managers would have taken me out.”

The Mets were unsettled at second. Phil Linz had little left and prospect Ken Boswell was unproven. The team was set at short with the light-hitting Bud Harrelson, an aggressive team leader. Harrelson, however, had military obligations that required his occasional absence from the team and he would need backup.

Weis’s Mets debut was memorable, though hardly auspicious. Five games into the season, Hodges inserted him at shortstop in the leadoff slot against Houston in the Astrodome. As the game stretched on to 24 innings, Weis went 1-for-9 with a walk—starting the season with an immediate slump—and then allowed a grounder to roll through his legs, an error that gave the Astros the only run in the longest 1-0 game in history—and at the time it was the longest night game ever played. Two days later, in his Shea Stadium debut, there were some boos but Weis had 2-for-4 afternoon with an RBI that helped lift the Mets over the Giants, 3-0. He was accepted.

With Boswell hampered by a broken finger and Harrelson performing his patriotic duty, Weis appeared in 29 games at second and 59 at short, and his .172 batting average helped “power” the Mets to a 73-89 ninth-place finish, 24 games behind the St. Louis Cardinals. Weis did manage one home run during the “Year of the Pitcher,” collected off Cecil Upshaw in Atlanta. It was his first career home run batting left-handed, his fourth homer in seven seasons in the majors, and his first since 1965, when he’d homered off Minnesota’s Dick Stigman. His first career home run had come off Cleveland’s Tommy John in 1964 and his second came later that year against Baltimore’s Dave McNally, which is worth noting.

By 1969, Weis’s career was at a crossroads. He was a 31-year-old utility player coming off a .172 season with a club one game out of last place. One factor in his favor was the condition of Harrelson, who had undergone knee surgery and still had military obligations.

Ever adaptable, Weis took steps to increase his value to his team. His playing weight was usually given as 160 on a 6-foot frame but was likely even less than that. The sportswriters’ preferred adjective for him was skinny. So, in the offseason, his wife, Barbara, loaded him up with pasta and beer and his weight edged up to 170. By July, however, he would be worn back down to 160.

Weis’s fielding remained steady, but improvement was clearly called for in his offensive statistics. Being a switch-hitter should have made him appealing to Hodges, who believed firmly in the platoon system, but he wasn’t pulling his weight at the plate from either side. With Boswell and rookie infielder Wayne Garrett both left-handed batters, Weis decided to only bat right-handed—his natural inclination—and remained a right-hander for the rest of his career.

Divisional play commenced in 1969. In the National League’s Eastern Division, the Cardinals, pennant winners three of the previous five seasons, collapsed as Leo Durocher’s Cubs, who had suffered the ignominy of finishing last behind the Mets as recently as 1966, surged into first. After an 11-game winning streak, the Mets were solidly in second place, 5 ½ games behind the Cubs, in early July.

On July 8, the Mets began the first crucial test in the franchise’s history. They were scheduled to face the Cubs for three games at Shea Stadium, then the expansion Montreal Expos for four games at Shea, followed by a three-game foray into the Cubs’ lair at Wrigley Field.

Sergeant Bud Harrelson was in the midst of his two-week summer training with the Army Reserve. Hodges penciled Al Weis into the starting lineup at shortstop, batting eighth. With a three-run ninth-inning rally, the Mets took the first game against the Cubs, 4-3. The next night, before a record crowd of 59,083, Tom Seaver pitched a one-hit, 4-0 shutout as Weis had a 1-for-4 night with a run scored. The Mets dropped the third game, and then the Expos came to town and beat the Mets 11-4, Weis again having a 1-for-4 game. The next game was rained out.

In the meantime, Harrelson rejoined the squad. In his absence, the team had gone 9-7 with Weis doing a fine job, playing every day, including both games of doubleheaders. The clubhouse man had even placed a sign reading “Iron Man” over Al’s locker. He played both ends of the doubleheader with Montreal necessitated by the rainout, which the Mets swept. Weis went 3 for 8 with a double and an RBI.

The next day, at Wrigley, “the little White Sox has-been,” as the Cubs’ Bleacher Bums referred to him, had one of New York’s six hits in a 1-0 loss to drop six games behind the Cubs. On July 15, Weis’s name appeared in the Mets’ lineup again. Asked if he had given any thought to supplanting Weis with Harrelson, the taciturn Hodges responded, “None.”

“Gil’s saving me for the World Series,” Harrelson joked.

Weis led off the third inning with a single and came home on an Agee triple to put the Mets ahead, 1-0. He came up again in the fourth with two out, the score tied, 1-1, Art Shamsky on third, and Ed Kranepool on first. On the mound for the Cubs was right-hander Dick Selma, a member of the Mets for the previous four seasons. Three breaking pitches got the count to 1-2. As Weis choked up on his 35-ounce bat, Selma came in with a fastball.

Weis swung, connected, and—to the stupefaction of Cubs and Mets players and fans–the ball sailed over the left-field bleachers and out onto Waveland Avenue, putting New York up, 4-1. It was such a rare occurrence that Weis had to remind himself, “Be sure and touch every base.”

The attention was all on Weis in the clubhouse following the 5-4 win. The three-run homer, only his fifth home run in eight years, had come at an opportune moment. “Once, when I hit a homer for the White Sox, I came into the dugout and all the guys were lying on the floor like they were dead or passed out from shock,” Weis told reporters.

Asked if he was surprised when the ball went out, Weis admitted, “I’m always surprised.”

“With two strikes on me, I choke up on the bat and just try to make contact,” he said. “Let’s face it. I’m no home-run hitter. I’m not even a hitter. I know my place on this club. I’m a fill-in man. I’m a substitute.” Or, as some called him, Supersub.

Weis was back in the lineup the next day and Hodges received no leading questions about putting him in there this time. With the Mets holding on to a 6-5 lead, he led off the fifth by driving a Rich Nye hanging curve into the bleachers. In two days, he had hit half as many as many home runs as he had in the previous 4½ years. The Mets won, 9-5. Afterwards, an exultant Tom Seaver declared, “I have a press release. Al Weis is only 483 years behind Babe Ruth.”

In these “crucial” nine days, the Mets won six of nine games and had closed the Cubs’ lead to four games. Weis started all nine games at shortstop, played every inning in the field, helped turn nine double plays, and went 9 for 34 for .265 at the plate with five RBIs, a double, and those two shocking home runs.

After the All-Star break, however, the Mets slumped. They slipped to 10 games behind the Cubs by the middle of August…and then the Mets were unstoppable. The Mets went 38-11 the rest of the way, claiming first place on September 10 and clinching the division two weeks later—with Weis’s pivot on a game-ending double play setting off a raucous celebration at Shea. Having gained 18 games on the Cubs in seven weeks, the Mets beat them on the next-to-last day of the season at Wrigley and closed at 100-62.

Al Weis was one of a roster of heroes whose contribution to the success of the team was not fully told by his .215 batting average in 103 games with 53 hits, 23 RBIs, 20 runs, nine doubles, two triples, three steals, and those two home runs.

In the National League Championship Series, the league’s first, the Mets swept the favored Atlanta Braves in three games. Weis appeared in all three games as a defensive replacement and went hitless in his lone at-bat.

It appeared as though his contribution to the Mets’ success might have run its course as the team headed to the World Series against the favored Baltimore Orioles (109-53). The Orioles pitchers were well aware of Weis’s batting tendencies from his days in the American League. Yet the little second baseman turned into their tormentor.

Even in the Series opener, won by the Orioles, 4-1, Weis drove in New York’s only run with a sacrifice fly. In Game Two, with the score 1-1 in the top of the ninth, Ed Charles and Jerry Grote singled and Weis came up to face the 20-winner Dave McNally with two outs and Mets pitcher Jerry Koosman on deck. Weis drilled the first pitch into left field to drive Charles home for a 2-1 lead that held up to give the Mets their first World Series win and tie the Series going home to Shea Stadium.

The Mets took Game Three with a 5-0 combined shutout by Gary Gentry and Nolan Ryan—the game best remembered for Agee’s brilliant catches and the one game in the Series started by a Baltimore right-hander. In Game Four, Ron Swoboda made a miracle catch of a ninth-inning drive, holding the Orioles to one run. Seaver retired the side in the 10th and in the bottom of the inning, Grote led off with a sun-aided double. Rod Gaspar was sent in to run. Weis was due up, but he was walked intentionally. When J.C. Martin followed with a bunt, the throw to first hit him on the wrist and bounded away, allowing Gaspar to score the winning run. The Mets were a game away from an unfathomable world championship.

It looked like Mets dreams would have to wait as the Orioles built a 3-0 lead in Game Five on home runs by Dave McNally and Frank Robinson in the third inning. In the sixth, the Mets won an argument that Cleon Jones’s well-polished shoe was hit by a pitch and Donn Clendenon followed with a home run to make it a one-run game. In the seventh, batting against McNally—shades of their 1964 confrontation—Weis hit a fly ball over the head of ex-teammate Don Buford that cleared the 371-foot sign for the first home run he’d ever hit—or would ever hit—at Shea. It was also the only home run he ever hit at a home park. Talk about timing!

The game tied, Jones doubled leading off the eighth inning and Swoboda laced another double to drive him home. For good measure, Swoboda scored on an error to make the score 5-3. Weis went down looking to end the inning, but few people noticed as fans started thinking about the ninth inning. After a leadoff walk by Koosman, Weis fielded a grounder for a force play and then two fly outs made the Mets world champions and the Shea Stadium turf—and everything that wasn’t nailed down—was fair game to the ecstatic throng.

Among the Miracle Mets there was none more miraculous than Al Weis. He led both teams’ regulars in the Series with a batting average of .455, more than double his regular season average. He had a 5-for-11 Series with a home run, four singles, four walks, and three RBIs—one of which won Game Two and other tied Game Five. His slugging percentage was .727 and his on-base average was .563.

Donn Clendenon, with three home runs, received the Series MVP Award. Weis’s achievement did not go unnoticed, however. The New York chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America voted him their Series MVP award, known as the Babe Ruth Award. It marked only the fourth time that the Babe Ruth Award, given out annually since 1949 (compared with the Series MVP that had been doled out since 1955), had not gone to the same man who won the MVP.

The Mets put up a good fight in 1970 and went into September in the midst of a tight race with Pittsburgh and Chicago. They faded, however, and finished in third place at 83-79, six games behind the Pirates.

Harrelson was a fixture at shortstop and Boswell and Garrett saw more action than Weis, who appeared in 75 games (44 at second and 15 at short) and batted .207 (25-for-121) with one final home run (against future Hall of Famer Steve Carlton). Weis, by then 33 years old, began his 10th major league season and fourth with the Mets in 1971. Harrelson was still ensconced at short, Boswell filled the bill at second, and a prospect named Tim Foli was coming up.

Less than two years since leading all World Series batters, Weis had trouble getting untracked. He had appeared in only 11 games through June 23, starting just once and going 0 for 11. The handwriting was on the wall. On July 1, the Mets released Weis. Hodges told him it was one of the toughest decisions he’d ever had to make.

Weis’s totals were 800 games played; 346 hits in 1,578 at-bats for a .219 average; 45 doubles, 11 triples, 115 RBIs, 195 runs scored, 117 walks, 55 stolen bases, and seven home runs—eight, if you want to count his second home run off McNally.

Weis quietly left the world of baseball. He and Barbara continued to raise their family in Elmhurst, Illinois, their home for decades. His avocation became golf and, though he declined to dwell upon his past, the family basement became a shrine full of baseball photographs, his old mitt, and his hot ’69 bat.

“I started four of the five World Series games, and I got into the fifth game as a defensive replacement,” he recalled. “I would have considered myself lucky to have played in even one game. Think of all the really great players who never got into a World Series, guys like Ernie Banks and Billy Williams. I was lucky just to get the chance, and then I was fortunate enough to perform well.”

Last revised: June 1, 2019

Sources

Allen, Maury. The Incredible Mets. New York: Paperback Library, 1969.

Cohen, Stanley. A Magic Summer: The ’69 Mets. (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1988.)

Neft, David S., Richard M. Cohen and Michael L. Neft. The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball. 24th edition. (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2004.)

The Baseball Encyclopedia, 9th ed., (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1993.)

Topps Baseball Card #313: Al Weis, 1968.

The Ultimate Mets Database.

Full Name

Albert John Weis

Born

April 2, 1938 at Franklin Square, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.