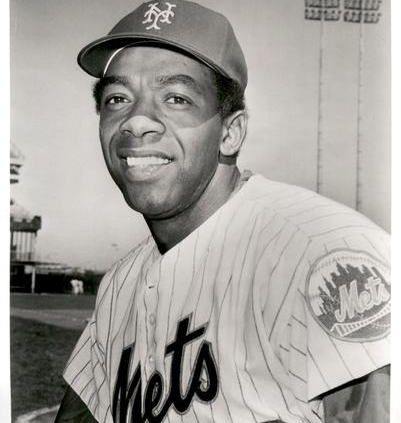

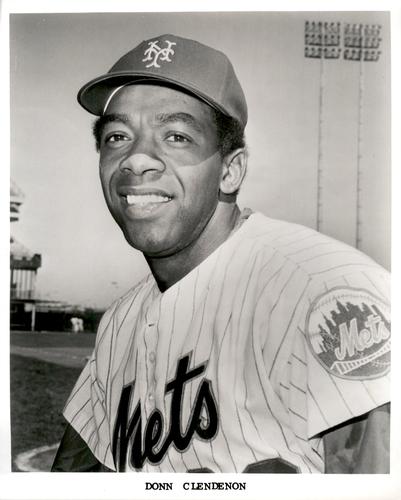

Donn Clendenon

His big brother in college was Martin Luther King Jr.

His big brother in college was Martin Luther King Jr.

Somehow, it’s appropriate to begin with that fact when discussing Donn Clendenon. During his college years at Morehouse College, one of the most pivotal players in Mets history was mentored by the greatest and most pivotal African American of the 20th century. The big brother tradition for “Morehouse men” typically assigned juniors and seniors to incoming freshmen, but the King family knew the Clendenons well, and the future legend Martin Jr.—though he had already graduated from “The ’House,” continued his studies at Crozer Theological Seminary, and received his ordination—volunteered for the duty.

If Ed Charles’s remarkable baseball life was set in motion by being present as history was made by Jackie Robinson, you’d figure it would be hard for a teammate to have a bigger claim at being touched by greatness, but there you have it. As the Nobel laureate King would go on to almost define the civil-rights movement which culminated in many of the cultural upheavals of the 1960s, his protégé’s modest contribution to that era would be as the final piece of the puzzle of the storied championship baseball team that capped the decade and captured the nation’s imagination, a year after the murder of his mentor threatened to tear the nation apart.

It’s just too good a story when it’s told that way. But, while that’s all true, it’s too easy to paint King as the figure who set Donn Clendenon’s remarkable baseball life in motion, but Donn would have told you that such an honor could only belong to Nish Williams.

Donn Alvin Clendenon never knew his father, a double Ph.D. who taught mathematics and philosophy at Langston University, an all-black state university in Oklahoma. Claude Wendell Clendenon was just 32 when he died of leukemia, and his son only six months old. Growing up in a strictly segregated Atlanta, Donn had the fortune to be born into a comfortable middle-class family, and a mother strong and wise enough to step out of her mourning and go to work for the Scripto Pen Company (a huge employer of Atlanta blacks at the time) and to raise him with his father’s intellectual ambition. (Donn graduated from high school at 15, a lone B-plus robbing him of a valedictorian status in his high-school class.)

But Donn also had a hero. He was six when his mother remarried, to Nish Williams, a successful restaurateur in black Atlanta and a 13-year veteran of the baseball’s Negro Leagues, playing for several teams, primarily the Nashville/Columbus/Washington Elite Giants. Spending much of his career as a catcher noted for his arm, Williams moved around the diamond a lot, and was knocked into the outfield when the legendary Biz Mackey joined the Elites and became their backstop.

Nish raised his stepson with all the attention and pride one could hope for out of any biological father, and brought a baseball knowledge comparable to Claude Clendenon’s academic prowess. A player-manager with the Atlanta Black Crackers, Williams continued to play and coach semipro ball after his retirement, and worked for many years as an unpaid assistant coach with his alma mater, Morehouse. No less than Satchel Paige once credited Williams with being the only man who got around on the famed “hummer”—Paige’s legendary fastball. It was Williams, too, who fine-tuned young Roy Campanella’s catching skills.

It was an environment a boy with baseball ambitions could only dream of. Baseball was the “language” spoken by the denizens of the family restaurant, many retired and active ballplayers among them. Clendenon lists them all in his biography: Paige, Campanella, Jackie Robinson, Joe Black, Don Newcombe, Dan Bankhead, Sad Sam Jones, and more. When a 10-year-old Donn was exhibiting an aversion to getting hit by a thrown ball, his stepfather took him one evening to a local high school field where no less than Paige and Jones were assembling a wooden cage. The plan was for Donn to stand in the cage without a bat while the legends pitched and Nish caught, assigning Donn to identify the pitches as they crossed the plate. The caveat was that the cage was open only on the side facing the pitcher, leaving Donn vulnerable on that side, but unable to bail to any of the other three.

The experiment worked initially, as Paige’s legendary control kept the ball over the plate. Donn wasn’t so fortunate with Jones, however, receiving a welt on his backside from Sad Sam’s first offering. But the greater humiliation was when Jones released his curveball—starting behind Donn’s head, sweeping across the plate, and triggering the child to wet his pants somewhere in between.

Decades later, an outstanding 1970 season by Clendenon triggered an unexpected congratulatory phone call from James “Cool Papa” Bell. Bell, just scraping by at this time in his life, followed with a tearful apology for missing Williams’s 1968 funeral, and Clendenon reciprocated the honor of the call with an invitation for Bell to visit the Mets clubhouse—regaling Mets both black and white with stories of the old times and the players to whom they were all indebted, transfixing them in the sort of major league locker room he himself had been barred from in his playing days.

But despite the environment of his upbringing, it wasn’t baseball ambitions that drove Clendenon, and he resisted his stepfather’s vision of stepping into Nish’s spikes even as he grew into an athletic frame out of proportion with that of the son of an academic. Like many young men, Donn sought to define himself on his own terms rather than his parents’, preferring UCLA to Morehouse, and basketball and football as better suited than baseball for his powerful body. But a conspiracy was afoot. With his bags packed for California, his family received a visit from a pair of Morehouse professors/coaches, who told his mother the 16-year-old freshman was too young to head across the country to UCLA. She bought the argument, went upstairs, unpacked Donn’s bags, and he was headed to Morehouse, where the best and brightest of black Atlanta typically went. Clendenon’s initial plan was to rebel by refusing to go out for any sports (he was attending on an academic scholarship), but his stepfather persuaded him to join the football team merely as the substitute punter when the regular punter was hurt, and Clendenon’s competitive instincts did the rest. On his first play, he faked his kick, ran 55 yards for a touchdown, and his athletic career was restarted in earnest.

It can’t be understated what it meant to be a “Morehouse man” at that time in history. “It was well known,” Clendenon states in his biography, “that 80 to 85 percent of the African-American medical doctors and lawyers in the United States were graduates of Morehouse College.” One may suspect that figure is disputable (certainly a Howard University man might), but even if it is, Clendenon’s faith in it speaks of the stature the school held for black Atlantans, as well as African-Americans across the country. Be it his mother’s dream of his becoming a doctor, or his stepfather’s dream of his becoming a professional athlete, he was at a place that they both trusted of their own dreams for him. The advocacy of the coaches and professors and their high-pressure recruiting ploy, and his adoption by the King family could only underscore this point. King fulfilled the big brother’s job—helping Clendenon adjust to the school over occasional dinners in the King home. Clendenon had an open invitation to drop by, and if Martin Jr. wasn’t there, he had the ear of Martin Sr. (Class of 1926 and future trustee of the school); Martin Jr.’s wife, Coretta Scott King; or Martin’s influential sister Christine King (a 1948 graduate of Spelman, Morehouse’s sister school, and the alma mater of Clendenon’s and King’s mothers). And if not that, the young athlete could appreciate the home-cooked meals.

Greatness was all around and simply expected of Morehouse men. Clendenon wasn’t the youngest person in his freshman class. That honor belonged to 15-year-old Maynard Jackson, who went on to become Atlanta’s first black mayor. Donn starred in sports, but he was careful to think of sports as an avocation rather than a vocation. He considered a possible career as a high school teacher and coach, and his first job after graduation was teaching fourth grade and coaching. His education taught him not only to view the slim long-term prospects for a career in sports, but the narrow realities of the nominally integrated baseball scene of the ’50s. Yes, black stars could find work, but how many marginal bench players of color would a team carry? Yes, an African-American player could get a chance in uniform, but would any team allow that player a chance to be a manager or executive when his playing days ended?

Nish Williams wasn’t ready to give up on Donn. He had coached him on the semipro Atlanta Black Crackers during his summers, but the colder weather months concentrated Donn’s thinking on the cold reality that his mind and education were his best assets in pursuing a success in life, and helping his family, his community, and his society—as he was raised and taught at “The ’House” to do. (And Clendenon was acutely aware that there were no guarantees there either—his postman had a Ph.D. in physics!) Williams convinced Donn that he could have a true vocation, but that perhaps a career of a dozen or so years in his avocation as an athlete would help establish his name as a professional asset.

The competitor in Clendenon again could not resist the argument. But Williams’s job was only half-done. The 6-foot-4, 215-pounder graduated with 9.6 speed in the 100-yard dash, and that and the dexterous hands had the Cleveland Browns interested. And football players weren’t asked to apprentice in the minors. But as at so many crossroads in Clendenon’s life, he found legends to help steer him. In 1956, the oddly named 100 Percent Wrong Club, made up of black civic leaders of Atlanta, named Donn the College Athlete of the Year and Jackie Robinson the Man of the Year. Stuck at the banquet next to Robinson and keynote speaker Branch Rickey, Clendenon found his resistance futile as Rickey’s silver tongue worked its magic and the stately Robinson—who himself was more highly celebrated on the gridiron in his own college days—provided the model of what he could become. Clendenon may have wondered if Rickey, Robinson, and his stepfather had planned it all out beforehand.

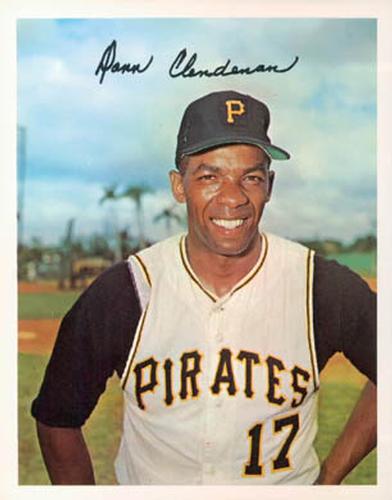

Convinced by Rickey that baseball would spare him football’s high risk of a career-ending injury, he accepted an invitation to attend a Pittsburgh Pirates tryout camp in 1957—no contract in hand. Clendenon received 10 days of leave from his teaching assignment, got some last-minute advice from Nish (“be yourself; relax”), arrived in Jacksonville, and was assigned the cap and number 317. Over 500 hopefuls spread out over the six-diamond complex and were assigned to games. While Donn knew several players from his amateur and semipro experience, his own reputation hadn’t preceded him. Pitchers sized him up, went with the notion that big men can’t handle the curve, and fed him a steady diet of benders. His lessons with Sad Sam and Satchel paid off, and he clobbered the ball. He went through throwing drills and 60-yard dashes, running future All-Star Julian Javier to a draw. At the end of the day, the black players were sent to bunk with local black families. The next day, the names of players who were to report to management for a bus ticket home were posted, and for nine days, Clendenon’s name didn’t appear. His leave of absence being up, however, with no word on his status, he grew miffed, caught a plane back to Atlanta, and went home.

Donn returned home to several messages from the Cleveland Browns and a contract in the mail from the Harlem Globetrotters. He brooded over the weekend and considered his options. Reporting to school the next morning, he found two new students in the back of his class, Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown and minor league director Branch Rickey Jr. They apologized for the misunderstanding, stating that they had intended to offer him a contract on his final day in camp. (Javier was the only other survivor of the 500.) Showing all of the flair and tightfistedness of Rickey Sr., they offered him a contract right there in the school—for $500 (nearly $5,000 in 2009 dollars). He went home, considered the challenges of the minors, the limited opportunities for blacks, and the reality that the only two black Pirates—Roberto Clemente and Roman Mejias—were Afro-Caribbean. He knew he could play at the top level immediately in basketball and football. He talked with his parents, and let his heart cross up his head. He signed.

Donn returned home to several messages from the Cleveland Browns and a contract in the mail from the Harlem Globetrotters. He brooded over the weekend and considered his options. Reporting to school the next morning, he found two new students in the back of his class, Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown and minor league director Branch Rickey Jr. They apologized for the misunderstanding, stating that they had intended to offer him a contract on his final day in camp. (Javier was the only other survivor of the 500.) Showing all of the flair and tightfistedness of Rickey Sr., they offered him a contract right there in the school—for $500 (nearly $5,000 in 2009 dollars). He went home, considered the challenges of the minors, the limited opportunities for blacks, and the reality that the only two black Pirates—Roberto Clemente and Roman Mejias—were Afro-Caribbean. He knew he could play at the top level immediately in basketball and football. He talked with his parents, and let his heart cross up his head. He signed.

It was back to training in Jacksonville for his first season with the Jamestown Falcons (Class D, New York-Penn League), and a long bus ride between Florida and upstate New York. Clendenon counted six other black players, but all Dominican (including Javier) plus a Virgin Islander (Elmo Plaskett). In 180 at-bats at Jamestown, Donn posted a .239 batting with six doubles, three triples, and only one home run before the team ceased operations in midseason due to some combination of bad weather, low attendance, and a local ordinance prohibiting ballpark beer sales. The players went their separate ways with different assignments, and Donn was told to stay at the local YMCA and await instructions. Three weeks later, he was assigned to Salem, Virginia, in the Class D Appalachian League.

Minor league ball in the South was still quite a burden for a black player in 1957, and playing for a team called the Rebels can really put things in context. Black and Hispanic players were again assigned to stay with black families rather than lodging with the white players. But Donn relaxed a little, put up a .275 average, with nine doubles, three triples, five homers, and a hundred calls to his stepfather.

His avocation in gear, his vocational work was mostly limited to substitute teaching in the offseason. But Clendenon’s entrepreneurial spirit kicked in during his next season in Grand Forks, North Dakota, of the Class C Northern League. He asked for and got the clubhouse duties and was paid $5 by each player for laundry and shoe-shining service. No bootblack, he subcontracted the work to high schoolers, both at home and on the road, supervising them for quality assurance.

The season was another cultural jolt for Clendenon. There was one black family within about 100 miles, and he found himself fixed up with their daughter for the sole purpose of keeping him away from white women. The matchmaker was the team’s general manager.

His play continued to progress, however, particularly his power stroke. Getting 453 at-bats, he hit .265 with 21 doubles, 12 triples, and 10 home runs while driving in 70 runs. His season ended a week early with a draft notice. With the intervention of the parent Pirates, Clendenon was placed in the Army Reserve and assigned to basic training at Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina. Despite his athletic prowess and zeal, he found himself prohibited from playing for the base basketball team, which was the province of the regular Army, and not reservists. Again, greatness intervened, as the base commander, the World War II hero General Mark Clark, did some fancy footwork. Clendenon remained a reservist, but his dog tags said Regular Army. Clark wanted a basketball championship for his base, and Clendenon starred for the team over the next four months, and lived the privileged life of a base jock, with Clark himself intervening if a superior tried to dress Clendenon down. For his part, Donn led the base team to the championship, and was discharged in time for spring training in 1959 in the best shape of his life.

He led the Pirates in every offensive category that spring, but when minor-league camp opened in Jacksonville (where the black players were housed above a black nightclub, and were kept up at night by the music and prostitutes), he was reassigned. When the season opened, it was the Class B Wilson Togs of the Carolina League for him. His torrid spring continued into April, and several weeks into the season he was hitting .370 when reality struck him square in the face. It was only the second integrated season for the team, and Wilson had nine African Americans in uniform. When the team was referred to as “the Black Togs” in the local press, the parent club demoted the team’s offensive leader—Clendenon—to Idaho Falls in the Class C Pioneer League. The same pride that led him to head home from Jacksonville tryouts two seasons earlier was again stirred, and he packed his bags for home.

Nish Williams, whose color denied him a chance even at C ball, would have none of it, and told his stepson so. Clendenon contacted the Cleveland Browns, but Branch Rickey Jr. had learned from his father just how powerful the reserve clause is, and the Pirates’ refusal to give Donn his release kept him out of the NFL. With Clendenon ready to sign with a Canadian baseball team, Rickey Jr. for the second time made a trip to Atlanta to smooth some feathers. Satisfied that the organization was paying attention to him, Clendenon reported to Idaho Falls determined to prove himself.

He clobbered the ball. He hit .356 and had a slugging average of .599 in 105 games, hitting 15 homers and knocking in 96 runs. Rickey Jr. sent him a $5,600 bonus—$100 for every point of batting average over .300.

The 1960 season opened for Clendenon with the Class A Savannah Pirates of the South Atlantic League. With Atlanta only 250 miles away, the Sally League was home stamping grounds for Clendenon. Playing mostly in the outfield, he repeated his success of 1959, only this time earning the league MVP, hitting .335 and slugging an eye-opening .606. His 28 homers and 109 RBIs led the league. The season was also notable for some transaction drama. Clendenon received word that he was to report to New York, having been traded to the perennial champion Yankees. He pointed his car north with visions of joining Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle in the outfield, only to be pulled over in Virginia and informed by a state trooper that the trade was off.

Donn headed home hoping for a September promotion to the bigs. But the pennant-bound Pirates were conservative with their call-ups in order to preserve team chemistry. With a stunning swing from second baseman Bill Mazeroski, the Pirates defeated the Clendenon-less Yankees in the World Series. But there would be a New York championship in Clendenon’s future yet.

Clendenon started the 1961 season at a crossroads. He was 25, and had come off a remarkable minor league season. The Double-A and Triple-A levels, then more than now, were for retreads and emergency replacements, and a star player could expect to skip one or both of those levels on the way to the majors. Meanwhile, the world champion Pirates were loaded with batsmen, sporting Dick Stuart at first and Bob Skinner, Bill Virdon, and Roberto Clemente (already a legend though less than a year older than Clendenon) in the outfield. Though his life away from the game during his offseasons in Atlanta mostly consisted of substitute teaching and being a letter carrier, he remained convinced that a quota system was retarding his baseball prospects. He was farmed out to the Triple-A Columbus Jets and fumed. Perhaps that fueled his bat, however, because he put up his third straight MVP-caliber season, finishing second in the voting, but hitting .290, slugging for a .507 average, and adding 82 RBIs and 25 stolen bases. The Jets won their first pennant in more than 20 years, and when the season ended, Clendenon got the call.

He called his parents, and reported to the Pirates on September 9, 1961. He had spent five years in the minors, often asked to sleep, dine, and relieve himself in substandard facilities. At the age of 26, Nish Williams’ stepson put on a big-league uniform, and promptly sat for 13 days.

The pride didn’t get the best of him this time, however, and perhaps we can see greatness intervening again. After Donn’s call-up, Roberto Clemente came to his locker and invited him to a big party. After the party, he went home with Clemente, and lived with him for the rest of the season. Clemente, who had refused to identify himself as black in the minor leagues even as he was subjected to the same Jim Crow segregation as Clendenon, was establishing himself as the leader of the black players on the Pirates. It was a decade away—and Clendenon likely couldn’t have imagined it—but Clemente’s Pirates would grow into the first team to ever field an all-African American and Afro-Latin lineup. What Clendenon perhaps knew was that he had another legend in the making for a big brother. Another future martyr, as it turned out.

Clendenon waited his turn and again made the best of it, getting into only nine games after his call-up but batting .314. His future seemed secure. When Joe Brown asked him to join the squad of Pirates third baseman Don Hoak, who would be managing in the Dominican Republic, he took what looked like a good career opportunity, having previously played two winters in Puerto Rico. The highlight of this winter, however was helping to bail Hoak out of a barroom brawl, and fleeing the country admidst a bloody conflict. The assignment lasted all of three days, followed by three weeks holed up with other Americans in a resort hotel, before completing the winter season in Nicaragua, with no further uprising-related interruptions.

The next key figure to emerge was Dick Stuart, a legend mostly in the ironic sense of the word. Ralph Kiner, Frank Thomas, Stuart, and Clendenon form an interesting quartet as a succession of Pirates right-handed sluggers who would go on to make their marks in Mets history, and most of them notably, most of them having clashed with the Rickeys while with Pittsburgh. When the Pirates let go of Rocky Nelson after the 1961 season, that left Clendenon as Stuart’s backup at first. But backing up Stuart was a pretty secure position, for Dick, despite a shocking amount of power (he once hit 66 homers in the minors), was a disaster defensively. He was nicknamed Dr. Strangeglove and was booed regularly. Donn started the season platooning in left field with Bob Skinner and subbed for Stuart on defense. In the middle of the season, he was told that he would be the first baseman, was sent down to Columbus for a few weeks to get his timing, and tore the cover off the ball. He returned to Pittsburgh at the end of July and took his full-time role. With a .302 batting average, .477 slugging mark, and a .376 on-base percentage in 80 games, it was fair to say that he had arrived. When Chicago Cubs second baseman Ken Hubbs received 19 of 20 Rookie of the Year votes, the lone dissenting vote went to Clendenon. The end of the season also saw future star Willie Stargell called up, and Stuart was shipped away to Boston in November.

After he was called up to the Pirates in 1961, Donn was hired by the Mellon National Bank and Trust Company, training during the offseason and continued the following season during Pirate homestands. The tradition of players having offseason jobs (and the most loyal fans knowing where their favorites plied their trade) is a delightful part of baseball lore, but the thought of a young star continuing a second job during the season is potentially jaw-dropping to anyone used to seeing the impressively compensated athletes of today.

Also notable during the 1962 season was the birth of Donn’s son, Val Eric. Donn and Val’s mother risked scandal by electing not to get married, but both families were supportive and Donn proudly owned up to his fatherhood. Though the couple didn’t stay together, the boy was raised with the name Clendenon, and went on to follow in the family tradition as a Morehouse Man.

A player on the rise, Clendenon received no shortage of advice from fellow African-American players, to hustle, keep his drinking moderate, stay in shape—and avoid white women. His first season as a full-timer was a modest success; he hit .275 in 1963 but his slugging average was only .430. He also struck out 136 times, leading the league in that category.

Incredibly, Clendenon’s parallel career at Mellon Bank morphed when one of the Mellons persuaded him to go to work for Robert Duggan, the Pittsburgh area’s ambitious district attorney. While continuing to star with the Pirates, Clendenon became an Allegheny County detective working with juvenile delinquents, but with full arrest authority, bringing pride to Pittsburgh with his bat, and helping the community as best he could when the game ended. The job also exposed him to the courtroom for the first time.

In 1964, not wanting to be another Dick Stuart, Clendenon sought out Gil Hodges, his future manager with the Mets, to work on his play at first base. Hodges came up as catcher before converting to first and becoming a famed defender at first, the best ever to some judges. Jackie Robinson had always praised his former teammate’s character to Donn. Hodges had just started his managing career with the Senators, but when their teams’ paths crossed during that spring, he took the time to meet with Clendenon and help him work on his defense. The two got along and talked hitting as well. Clendenon had a similar season at the plate—hitting .282 with .446 slugging. His defense improved and he cut his strikeout rate. Meanwhile, Stargell broke through and excelled for the team, despite not having a position; Stargell, who hit the first home run ever at Shea Stadium that year, saw time in left, right, and center, as well as 50 games at first.

The other great Pittsburgh corporate giant besides Mellon Bank was U.S. Steel, and Clendenon left the D.A.’s office to work for the steel giant, training in its personnel department. But his experience suggested that it would take a law degree to get the kind of business success he was looking for. In August 1964, he applied to law school at both Harvard and Boston University, and was accepted at both. He elected for Harvard, and attempted to commute to Boston during the season. The experiment failed, and he dropped out, but remained determined. He would try again with Pittsburgh’s Duquesne University in 1965. Duquesne was not immediately open to his attempting to juggle his baseball career with law school, but the young ballplayer was able to make enough connections to not only help him gain admission, but to win a full senatorial scholarship and serve as a deputy clerk for a federal judge. Clendenon later said there were three blacks in the school, his constitutional law professor, the janitor, and himself.

The 1965 season was also Clendenon’s most productive to that point. Hitting .301 and slugging .467, he played in all 162 games. He finished second to Ernie Banks in fan voting for the All Star Game, but Clendenon was left off the squad nonetheless. Danny Murtaugh had joined the front office after the 1964 season, and was replaced as manager by Harry “The Hat” Walker—a minor star of the postwar years. A slap hitter and 1947 batting champ, Walker wasn’t shy about giving hitting advice, even to sluggers. Though Clendenon and Walker clashed, the first two seasons under “The Hat” were nonetheless productive. Having Stargell in the lineup with him and Clemente certainly didn’t hurt.

Pirates general manager Joe Brown, who initially encouraged Clendenon’s pursuit of his law degree, changed his tune in the 1965-1966 offseason, wondering out loud if his big first baseman was overdoing it. Clendenon bristled, but it was true that Clendenon, who had hit .300 and slugged .573 in August 1965, dropped to .255 and .363 when the fall semester started in September—and the Bucs dropped from 4½ to seven games out.

The 1966 Pirates earned their Lumber Company nickname, posting a team batting average 16 points higher than any other team in the league. Clendenon had the most productive year of his career, batting .299 with .520 slugging in 155 games, hitting 28 homers and driving in 98 runs. New Pirates center fielder Matty Alou joined the party, winning the batting championship at .342 (up from .231 the year before in San Francisco).

The Lumber Company was nonetheless pitching-poor, and finished third in 1966. The highlights of the season for Clendenon were his marriage to Deanne Marriott and the birth of his second son, Donn Jr. The family bought a home in the Pittsburgh suburb of Monroeville, becoming the first family of color in the neighborhood. The choice was more poignant in the light of his near-arrest with Roberto Clemente when the Pirates visited Houston that year. The sluggers’ crime was attempting to buy tickets to a movie. Two years after the Civil Rights Act, certain businesses in Houston still reserved their goods and services for white clientele only. Even in the splashy new Astrodome, black Pirates found themselves barred from the stadium’s nightclub, hours after they were the attraction on the field.

The 1967 season was a fallback year for Clendenon: He lost 50 points off his batting average and 150 off his slugging percentage. The Pirates were hard-pressed to match their numbers from the previous year (though Clemente had perhaps his finest season), and the team fell to .500. The players had grown increasingly frustrated with the volatile management of Walker, and the conflict came to a head, according to Clendenon, when he failed to get a bunt down against Bob Gibson. Walker called a mandatory bunting clinic for the next morning and received a brushback pitch from Clendenon’s roommate, Bob Veale. With the team ready to mutiny against Walker, Joe Brown brought back Danny Murtaugh to finish the season for the Bucs. Whatever reconciliation it brought, it couldn’t help Clendenon, who turned 32 on July 15 and was seemingly on the downside of his career. Brown couldn’t have been happy to see Clendenon post an even more flaccid September, hitting .197 and slugging .289 as the Pirates staggered home 20½ games back.

The 1968 season was Clendenon’s last in Pittsburgh. It was a tough year all around as his beloved stepfather, Nish Williams, was diagnosed with colon cancer. Clendenon had dropped out of law school, sold his home in Monroeville, and returned to Atlanta the previous off-season to be close to his family. The restaurant had fallen out of date, and Williams and Clendenon both saw that Donn’s management and now-famous name were needed if Williams was to leave a profitable legacy to his family. Willams was honored at the Atlanta Braves Old-Timers’ Day that spring. But his cancer surgery was unable to help him. In the end, neither was the morphine, and when Nish Williams died on Labor Day, 1968, his stepson saw it as a relief.

The ordeal contributed to another disappointing statistical season for Clendenon, and he was forced to more seriously shape his nonathletic aspirations. Apart from the family restaurant, he had taken a job in the personnel department at the Scripto Pen Company, where his mother had worked years before, after his father died. Placed between the mostly white management and the mostly black workers, he sought to improve working conditions, hired black foremen and forewomen, and actually encouraged unionization. When labor and management were at an impasse, he called local ministers, including his old big brother Martin Luther King Jr., and told them to preach to the workers to stand firm. When he encouraged the more volatile Stokely Carmichael to visit the factory, the company’s president dissented. Fortunately for Clendenon, that president was soon replaced.

King was assassinated in April 1968, and the loss of his now world-famous big brother combined with the decline and death of Nish Williams seemed to begin to weigh on Clendenon. Donn was also elected player representative for the Pirates, and the end of the season was a continual grind as he worked with his fellow reps to hammer out a new contract and avert a work stoppage.

A last key change in 1968 was Clendenon’s old mentor Gil Hodges taking over as manager of the long-struggling New York Mets. Under general manager Bing Devine the year before, the Mets had held a yearlong tryout camp, acquiring players, playing them for a few months, dealing them off, and getting a good look at their replacements, before perhaps dealing them as well. As Hodges assumed the manager’s position, Devine returned to the Cardinals having left Gil a solid nucleus to build on, led by pitchers Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Gary Gentry, and Nolan Ryan. Hitting was where the Mets fell short. Hodges opened the storied season of 1969 platooning at three positions, and moving men around when he had to.

Clendenon moved around as well. He was surprised to find himself not only exposed in the expansion draft, but claimed by the new Montreal Expos franchise. Saddened that his dreams of winning a championship with the Lumber Company were not to be, Clendenon’s fortunes seemingly changed when, with Jesus Alou, he was flipped in a trade to Houston, bringing Rusty Staub to Montreal. While the Astros had much better prospects for success, they also had a new manager, one Harry Walker. Though he tried to come to terms with another season under The Hat, whom Clendenon had long given up on as an unreformed racist, Clendenon could not come to terms with Houston’s front office. Considering the groundwork for his civilian life laid, Clendenon announced his retirement on March 1.

While the Astros tried to void the trade, the Expos had already begun marketing their team around “Le Grande Orange”—the Expos weren’t sending Staub back. Unable to unscramble the eggs, new commissioner Bowie Kuhn ruled that the trade stood, but that the Astros would be owed additional compensation from Montreal. Kuhn then asked Clendenon to meet with him, and he was accompanied by Scripto’s new president, Arthur Harris. Clendenon found himself surrounded by several owners—including Judge Roy Hofheinz of Houston and Charles Bronfman of Montreal. Harris was quickly told by the Lords of Baseball that he was unwelcome to speak. Clendenon was accused of being paid by a third party to retire. Harris later told Clendenon that after the meeting Astros general manager Spec Richardson passed on a threat from Hofheinz to buy Scripto and have Harris and Clendenon fired. The rational solution prevailed, however, and on April 8, Montreal sent Houston “additional compensation”—two players (including future All-Star Jack Billingham) and $100,000. Harris, somewhat shaken by the meeting and the threat, began encouraging Clendenon to return to the game. When baseball legend Monte Irvin appeared at the family restaurant with a generous three-year deal for Clendenon to report to Montreal, Clendenon at last agreed. The issue for management in the end didn’t appear to be the money (as it was to Clendenon), but that a player had asserted his rights.

Having skipped spring training, Clendenon was out of shape when he reported to Jarry Park in Montreal. Coming off two subpar years and dropping from a powerful lineup to an expansion team was a struggle. He opened the season with an 0-for-5 game against the Cubs, and despite a three-run home run in his second start, he struggled to catch up. With the security of a three-year contract and a lack of alternatives for expansion manager Gene Mauch, Clendenon used the next six weeks as his spring training. After 38 games, he was hitting only .240 with four home runs when the June 15 trade deadline rolled around. Donn received a call in his hotel room. “I want Clendenon,” the caller firmly stated.

“You can have him,” Clendenon jokingly replied. “He has a history of slavery and can be bought, but not cheaply.”

Who the joke was on is unclear. Mets general manager Johnny Murphy had asked the operator for his Montreal counterpart John McHale, but instead got Clendenon’s room. Realizing the mistake, and knowing Clendenon’s history, Murphy (in a move that would surely lead to a tampering complaint today) asked Donn if he would like to play for the Mets. Donn’s old mentor Gil Hodges, recognizing his team’s need for more offense, wanted Clendenon in his lineup, and Murphy completed the deal by sending Steve Renko, Kevin Collins, and two minor leaguers to the Expos. Though Murphy’s predecessor, Bing Devine, had turned over to him a more or less complete team, the deal that night was perhaps the only one of consequence Murphy made in building his championship squad.

When Clendenon arrived, Hodges privately told him that (1) he had watched his progress since they had worked together; (2) they were hoping to acquire him in the offseason before the Montreal claim; and (3) while Clendenon wasn’t keen on being platooned with Ed Kranepool, Hodges intended to use him thusly and gradually expand his role. Clubhouse manager Nick Torman assigned him the uniform number 22 and told him that he was “double deuce.” In baseball jargon, “number one” was a white person and “number two” was a black person. He noted that numbers 20 and 21 also went to star African-Americans—Tommie Agee and Cleon Jones, respectively. Tom Seaver made a point to remind Clendenon that Donn was his first strikeout in the big leagues.

Always a serious ballplayer, the soon-to-be 34-year-old Clendenon knew that part of what he was expected to bring to the young team was leadership. And to him, that meant loosening up, in order to help break the tension among a group of players in their first pennant race. Clendenon became the clubhouse jokester. When Wayne Garrett was in a batting slump, Clendenon took the time to praise his fielding, and then speculated that the rookie developed his dexterity through frequent masturbation. When Cleon Jones received a death threat, Clendenon suggested that his backside would make a better target for a gunman than his head. Later on, he told Cleon of the funeral speech he had prepared for him: “There lies a no-good mother-fucker who couldn’t pull a fastball to left field if his life depended on it.”

Jones, safely in the clubhouse, responded, “Clendenon, you probably sent the goddamn letter because you’re jealous I’m batting close to .360.”

None of that leadership would have worked as well, though, if Clendenon hadn’t brought his bat. And about two weeks into his tenure in New York, his lumber caught fire. From the second game of a doubleheader on July 1 through July 8, Clendenon appeared in six games and collected 10 hits in 26 at-bats. New York won the last five of those games. Donn provided the crucial edge in the last two games, including a three-run go-ahead homer against his old mates in Pittsburgh and a ninth-inning pinch-hit double against the front-running Cubs—after which he scored the tying run on a Cleon Jones double. In the postgame stories, Cubs manager Leo Durocher and captain Ron Santo both made a point of ripping their center fielder Don Young, who failed to catch up with another double that inning as well as Clendenon’s.

Maybe Clendenon’s most notable icebreaker came the next day, in perhaps the greatest game ever pitched by a Met. On July 9, with the Mets 4½ games behind Chicago, Tom Seaver was giving the visiting Cubs a performance that would not only gain the Mets a game, but also a dispiriting psychological edge. With eight innings gone, Seaver had retired all 24 Cubs to come to the plate, striking out 11 of them. With the Mets up 4-0, Cubs catcher Randy Hundley led off with a bunt, which Seaver crisply fielded. Coming up next was a little used rookie backup center fielder named Jimmy Qualls, of whom the Mets’ scouting reports said little. When Qualls singled cleanly, Seaver’s perfect game and no-hitter were lost.

From his position at first, Clendenon saw Seaver’s shoulders deflate and his head go down. Knowing that the team still needed a focused Seaver to finish off the win, he walked over to the mound and looked at Seaver. “All right, Tom,” he said, “you fucked up.”

Seaver, with a serious on-field manner hardened in the Marines, took such a challenge seriously: “I fucked up?” he responded.

“Yeah, Tom,” finished Clendenon. “You pitched a great game and I’m proud of you. We still have to finish the inning though, so don’t let down now.”

Seaver, refocused on the job at hand, recorded the last two outs without incident and walked off the field to a standing ovation.

Clendenon hit as he hadn’t for 2½ years. In a pitcher’s league, playing in a pitcher’s park, he batted .252 and slugged .455 for the Mets, with 12 homers and 37 RBIs in just 202 at-bats. Though he was particularly effective against lefties, batting .281 and slugging .474, he saw more time against righties as the season progressed, though Gil Hodges was careful never to completely abandon Ed Kranepool. When the Mets at last clinched the division and were faced with the first-ever National League Championship Series, the opposing Atlanta Braves started three right-handed pitchers. Not only did Clendenon get passed over in favor of Ed Kranepool in all three starts, he didn’t see a single at-bat as the Mets swept. Clendenon’s time was to come.

The 1969 World Series is known in part for the verbal sparring that occurred, and the new jocular Clendenon played his part. When Frank Robinson stated on the field, “No hard feelings, but you guys can’t beat us,” Clendenon replied that the Mets would “kick your ass, maybe in four straight games!” Clendenon’s confidence was boosted by the fact that Baltimore had two left-handers in their powerful four-man rotation, and were in fact cutting to a three-man rotation for the Series with southpaws scheduled to throw four of the first five games. Clendenon knew his at-bats were coming and was happy with how he was hitting lefties, but Game One didn’t work out so well. Tom Seaver scuffled, lasting only five innings, and lefty Mike Cuellar dominated the all-right-handed-hitting Mets lineup, to the tune of a 4-1 win. Clendenon, for his part, got two hits and scored the first World Series run in Mets history.

His confidence undiminished by the loss, Clendenon found the Mets clubhouse after the game otherwise. He asked Hodges if he could address the beleaguered team. Hodges agreed, and Donn started by letting Seaver off the hook. They had chased the team’s (and league’s) best pitcher, but the Orioles still didn’t dominate the game. “Gentlemen, trust me!” he shouted. “We have much better pitching than they do. Our pitchers are better and they throw a hell of a lot harder than (Baltimore’s) pitchers. Let’s not get down, and let’s look at what we can do if we just play our game.” He even mocked Cuellar, who hadn’t succeeded earlier with St. Louis and Houston, as taking refuge in the American League in order to succeed. Recounting his oration later, he sounded as chipper as a Shirley Temple character, finishing, “Trust me fellows! We will win!”

Game Two opened with a prediction more typical in its saltiness when Clendenon completed a batting-practice exchange with Paul Blair, telling the Baltimore center fielder, “We are going to send you home with your fucking heads between your legs.” Jerry Koosman no-hit the Birds through six innings and Clendenon opened the scoring with a fourth-inning home run, ending 23 straight scoreless postseason innings for southpaw Dave McNally. With the score tied 1-1 in the ninth, Al Weis singled in Ed Charles to put the Mets ahead. An Orioles rally in the home ninth brought on Ron Taylor for the save, and when Brooks Robinson grounded to Ed Charles, Clendenon was forced to dig Charles’s throw out of the dirt to record the final out.

Game Three at Shea was packed with celebrities as right-handers Jim Palmer and Gary Gentry matched up. Clendenon yielded first base to Ed Kranepool as the Mets won behind two spectacular Tommie Agee catches in center, 5-0. With the Mets up by a game now, Game Four was to feature a rematch of the opener: Cuellar vs. Seaver. Getting through the first inning scoreless this time, Seaver pitched like the ace he was, and Clendenon once again came through, turning on a full-count Cuellar fastball in the second and knocking it into the Baltimore bullpen for a 1-0 lead.

The Mets had been playing crisp defense the whole Series, and in the third, Clendenon took his turn. With two on and nobody out and Don Buford batting, Clendenon was positioned in for the bunt when Buford smacked a hard one-hopper his way. Reaching behind him for the ball as it shot past, Clendenon made the snag and got the out at second. A deft play by Seaver on a bunt and a Frank Robinson foul pop to Clendenon and the Mets escaped with their lead.

The score stood at 1-0 to the ninth, and Gil Hodges stuck with Seaver, even as the Orioles put runners at first and third with one out. When Brooks Robinson drove a ball to right-center, Ron Swoboda made a full-extension dive for one of the truly greatest catches in World Series history. Frank Robinson tagged and scored the tying run. Clendenon always maintained that Swoboda should have played the ball on a hop, that it was the go-ahead runner on first (who may have come around to score had the ball gotten by Swoboda). He made a point of spelling out his thinking to Swoboda when they got to the dugout. The Mets were fired up, however, and they won the game with a 10th-inning run as Rod Gaspar scored from second on a bunt play when the throw hit J.C. Martin on the wrist.

Game Five returned Koosman and McNally to the mound. For the first time since Game One, the Orioles took the early lead, on a two-run homer by McNally. Frank Robinson’s blast made it 3-0. It was still that score when the Mets batted in the bottom of the sixth, when Cleon Jones was apparently hit by a curve in the dirt, and the ball rolled into the Mets dugout. Clendenon asked umpire Lou DiMuro to check the ball for shoe polish, and when Hodges produced a smudged ball from the dugout, Jones was awarded first base.

With the Orioles angered by the call—Frank Robinson had been denied a similar call on an inside pitch from Koosman in the top of the inning—Clendenon waited out McNally. He hit McNally’s 2-2 pitch off the auxiliary scoreboard in left for his third homer of the Series, pulling the Mets within a run.

A seventh-inning homer by the light-hitting Weis tied the game. When a two-run rally in the eighth put the Mets up, Koosman closed out the side in the ninth. When Cleon Jones squeezed the last out, the Mets completed the most unlikely championship run in anybody’s memory.

As pandemonium broke out on the Shea infield, Clendenon made his way to the clubhouse to be told he had been named the Most Valuable Player of the World Series—despite strong cases for Tommie Agee, Jerry Koosman, and Al Weis (that winter, the second baseman would receive the Babe Ruth Award from New York sportswriters as the top player in the Series). Clendenon’s three homers tipped the scale in his favor for the prestigious MVP award. The last man to join the 1969 Mets stood the tallest at their hour of victory.

His MVP award came with a 1969 Dodge Challenger and he was immortalized in a painting by famed sports artist LeRoy Neiman (oddly enough, batting left-handed). Victory is fleeting, and Clendenon received a call at the stadium informing him that nothing of value was left in his apartment. “Fans” had broken in and taken almost everything—clothes, dishes, even wallpaper. Clendenon was given a penthouse suite at the Essex House while the place was restored, and enjoyed the pandemonium and tickertape parade in the World Series afterglow, but exhaustion led him to bail out partway through the route, and he absorbed a $500 fine from Gil Hodges—the same figure as his original signing bonus. He appeared with teammates on The Ed Sullivan Show, and in Las Vegas as part of a singing act with six other Mets. His celebrity, like that of his teammates but only enhanced by his MVP, was in full flower.

The story of Donn Clendenon and the Mets too often ends in 1969. In fact, he had quite a year in 1970. The Mets shocked a struggling Ed Kranepool, the last player from their inaugural 1962 season, by farming him out that season, nine years into his career, leaving first base the exclusive province of Clendenon. Donn responded with his best full season since 1966, one of his best ever, in fact, as he batted .288, slugged .515, clubbed 22 homers, and drove in 97 runs—a Mets record for RBIs at the time. But not enough magic was left, and the Mets fell to third place, six games behind his old Pittsburgh club. Clendenon was again overlooked at All-Star time, despite his manager’s picking the squad’s reserves (Donn never made an All-Star team), but he did finish 13th in league MVP voting. No Mets hitter would get that much consideration again until the mid-1980s.

But the third year of his unusual three-year contract showed age to be finally catching up with Donn. His 1971 numbers fell off, and, with Kranepool returned and resurgent, Clendenon again saw the majority of his time against left-handers, but he no longer showed an increased ability in those situations. Appearing in 88 games, he batted .247, slugged .411, hit 11 homers, and drove in 37 runs. Shortly after the season, he got his release from the Mets. He caught on with the St. Louis Cardinals for one final unproductive season (.191 in 136 at-bats), and retired.

Growing unhappy at Scripto Pen, Clendenon resigned shortly before the corporation was sold to the Wilkinson Sword company. In the summer of 1971, he joined General Electric as a management personnel consultant. He swept through training and hit the ground running that winter. Eventually, he was put in charge of recruiting minority candidates. When he attended a strategy session and heard a high-ranking officer lament the lack of qualified black candidates, Donn put his job on the line. Challenging the executive to produce 50 job descriptions with a salary range of $45,000 to $75,000, Clendenon promised to fill every one with a qualified black candidate or resign. Clendenon reached out to his Atlanta connections, including Vernon Jordan, a high-school classmate and future advisor to President Bill Clinton, developed a network, and filled each of the positions. His success rankled his rival, who vowed to get even, and Clendenon moved to the Mead Corporation as a management personnel consultant.

Clendenon eventually returned to Duquesne University and completed his law degree in 1978. He worked with Mead’s legal department before becoming a founding partner in Bostick, Gerren & Clendenon, practicing criminal law.

Like too many successful people in the 1980s—athletes and businessmen alike—Clendenon allowed himself to be seduced by cocaine. He went through rehab, and withdrew to the quieter lifestyle of Sioux Falls, South Dakota, where he became a certified addictions counselor. Even his sobriety was ambitious. He continued to practice law with the Minnesota firm of Clendenon, Henney & Hoy, and regularly attended Mets reunion events when his work and health permitted.

After a long struggle, Clendenon succumbed to leukemia on September 17, 2005, in Sioux Falls. He left behind his wife, two sons, his daughter, Donna, and a grandson, Alex.

Sources

Allen, Maury. After the Miracle: The 1969 Mets Twenty Years Later (New York Franklin Watts, 1989).

Amoruso, Marino. Gil Hodges: The Quiet Man. (Middlebury, Vermont: Paul S. Erickson Publisher, 1991).

Clendenon, Donn. Miracle in New York: The Story of the 1969 Mets… Through the Eyes of Donn Clendenon, World Series MVP. (Sioux Falls: Penmark Publishing, 1999).

Durso, Joseph. Amazing: The Miracle of the Mets. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1970).

Durso, Joseph. “Clendenon Is in Series Driver’s Seat.” The New York Times, October 22, 1969.

Goldstein, Richard. “Donn Clendenon, 70, M.V.P For the 1969 ‘Miracle Mets,’ Dies.” The New York Times, September 19, 2005.

Robinson, Tom. “Right Place, Right Time Fate Led Donn Clendenon to the New York Mets at a Propitious Moment. Some 25 years Later, He Revels in His Place in History.” The Virginian-Pilot, July 8, 1994.

Zimmerman, Paul D. and Schaap, Dick. The Year the Mets Lost Last Place (New York: The World Publishing Company, 1969).

Full Name

Donn Alvin Clendenon

Born

July 15, 1935 at Neosho, MO (USA)

Died

September 17, 2005 at Sioux Falls, SD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.