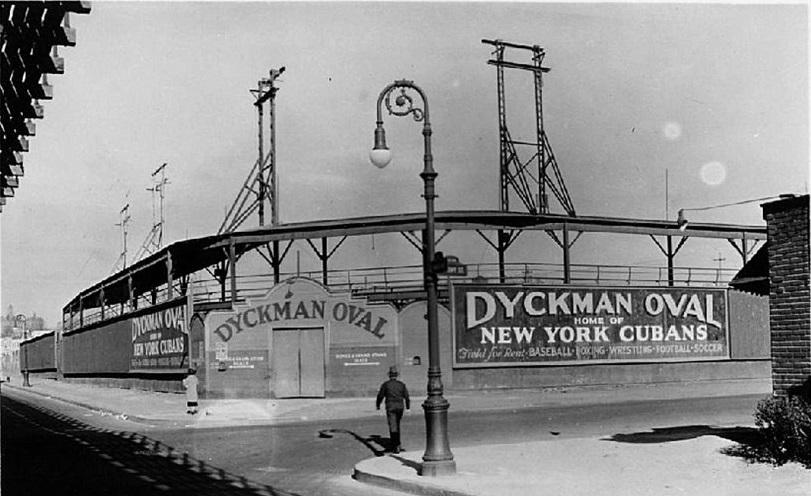

Dyckman Oval (New York)

This article was written by Rory Costello

This ballpark in the far northern reaches of Manhattan stood for just around two decades, from the late 1910s until 1938. Along with baseball, it hosted various other sports. Though no major-league games ever took place at Dyckman Oval, plenty of big-leaguers played in semipro games there. Babe Ruth came at least twice, in 1920 and 1935.

In addition, Dyckman Oval welcomed many elite Negro Leaguers over the years. They included such luminaries as Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Smokey Joe Williams, Louis Santop, and John Henry “Pop” Lloyd. Thanks to the efforts of another Hall of Famer, entrepreneur Alex Pómpez, the Oval briefly became “the real home for Negro [League] baseball in New York.”1 Another all-time great, Martín Dihigo, was player-manager of Pómpez’s New York Cubans of the Negro National League in 1935 and 1936.

Dyckman Oval was located in the Inwood neighborhood, near Inwood Hill Park, bounded by Nagel Avenue, Academy Street, Tenth Avenue, and 204th Street. In Ballparks of America (1989), Michael Benson wrote, “One of the most beautiful locations in America, the Oval is on a low plain, the only flat land for miles, surrounded by rocky and woody hills, with the blue span of the Henry Hudson Bridge crossing the Spuyten Duyvil Creek to the Bronx, beyond left field.”

Most of the tract on which Dyckman Oval was built belonged to James N. Butterly, who for many years was one of the largest landholders in the neighborhood.2 SABR member Bill Lamb, whose particular interests include the history of New York City and its old ballparks, described Butterly as “an unscrupulous character given to the manipulation of mortgage lenders, assignments of convenience, silent partners, dummy corporations, and elaborate financing schemes — rather than use of his own cash — to bankroll his property purchases.”3

The earliest known record of baseball at the Oval comes from April 1915. The home team was the Kingsbridge Athletics, who came from a neighborhood close by in the Bronx.4 That May, the New York Fire Department’s baseball team met the Athletics in the feature game of a doubleheader.5 Semipro and amateur ball continued there over the next several years.

The label “Dyckman Oval” sometimes referred only to the ballpark; at other times it referred to the larger piece of real estate on which the lot was situated. An aerial photo from 1914 shows the undeveloped site. According to the record of the 1932 court case Butterly v. Maribert Realty Corp., the Dyckman Tract parcels acquired by Butterly (via one of his corporate alter egos, Northern Terminal Corporation) were vacant property in April 1917.

One may infer that early ballgames at Dyckman Oval were played on a diamond without surrounding stands. In April 1917, the New York Sun reported that the Oval was fenced and a grandstand built for the coming season, through the activity of the Kingsbridge Athletics. The team opened its season on Sunday, April 15, against the Cuban Giants. Among other players, the article mentioned who was probably the first major-leaguer to appear at the Oval: George Browne of the Athletics, then 41, who’d last played in the big leagues five years before.6

Later that year, Browne was followed by former Philadelphia A’s hurler Andy Coakley. Coakley, then in the early years of his long run as head baseball coach at nearby Columbia University, was still pitching on occasion and had joined the Kingsbridge squad. On July 1, 1917, he defeated the Bushwick Club of Brooklyn in the second game of a doubleheader, 4-2. The Brooklyn Standard Union wrote, “Coakley, while hit hard, was there in the pinches.”7

A few months later, another former Philadelphia A’s star, Hall of Famer Chief Bender, came to the Oval. On October 20, 1917 (just three weeks after his last game for the A’s), Bender led a barnstorming squad against the Kingsbridge club. He pitched his team to an 8-4 win, helping his cause by scoring two runs.8

Andy Coakley was in action for Kingsbridge again in 1918. At least twice, he faced the Grand Central Red Caps at the Oval. The Red Caps were a black semipro nine that took on all comers, including white teams. The manager of the Athletics, Connie Savage, also added Bronx native Heinie Zimmerman near the end of August 1918.9 Zimmerman joined Kingsbridge after the major-league season ended on September 2 — early, because World War I was being fought.

Various other members of the New York Giants took part in games at the Oval during the fall of 1918. Two came against a black team, the Philadelphia Giants. The Polo Giants (a.k.a. Wendell’s Giants) were a team representing a New Jersey shipyard. On October 27, before a crowd of about 2,000, manager Lew Wendell’s team won, 3-1, behind the pitching of Al Demaree.10 On November 3, Larry Doyle sparked a 4-1 win with two homers and a double. Ferdie Schupp started and went two innings before leaving with fatigue and a pain in his arm. Hal Chase made two dazzling plays at first base.11 A week later, the Giants (billed under the New York name) returned to the Oval to play the Paterson (New Jersey) Silk Sox for the benefit of the United War Fund Drive.12

Dyckman Oval’s first noteworthy regular teams arrived in 1919, the Treat ’em Rough Baseball Club and the Bacharach Giants. Treat ’em Rough, a semipro outfit formerly known as the Maroons, had been acquired by Guy Empey (who’d gained fame with his World War I memoir Over the Top). The roster featured former big-league pitcher Jeff Tesreau. Another hurler, Pol Perritt, joined after quitting the New York Giants that August. Manning first base was Marty Kavanagh. The Bacharach Giants were a black team from Atlantic City, New Jersey. The franchise had gained two new major investors: Barron Wilkins (a well-known Manhattan nightclub owner) and John Connor (a Brooklyn café owner and Negro League pioneer).

As author James Overmyer observed, “the involvement of New Yorkers Connor and Wilkins opened an important door to the Bacharachs. In 1919 Atlantic City was a good baseball town and Philadelphia was better, but if you could play in New York, the biggest, most famous city in the country that had a big neighborhood filling up with black folks, you could do really well.” Overmyer noted that Guy Empey forged an alliance with Connie Savage, who controlled bookings at the Oval. This alliance was also good for the Bacharachs.13

As the 1919 season began, Dyckman Oval had been turned into a regular ballpark. The stands had been covered, a turf infield laid out, “and other improvements made that will surprise uptown fans.” The Treat ’em Rough Military Band provided entertainment.14 A photo taken that July clearly shows the enclosed stadium, with the outside of the wall emblazoned “Treat ’em Rough Baseball Club” and a sign advertising “Live Baseball Every Sunday Afternoon.” For baseball, the Oval had a seating capacity of about 4,500. Larger numbers could be accommodated for other events, particularly boxing and wrestling bouts, if necessary. As yet, however, details about the financing, design, and construction of the stadium at Dyckman Oval have not become available.

The Treat ’em Roughs and Bacharachs faced each other too. On August 3, Tesreau won the opening game of a doubleheader, 2-1, outpitching Cannonball Dick Redding, who’d drawn comparisons to Walter Johnson. The Giants lineup included Spottswood Poles (leading off and playing left field) and Pop Lloyd (shortstop and cleanup batter).15

Soon thereafter, a strong opponent from the Midwest visited: Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants.16 That club included Oscar Charleston, who also pitched in those days.

As the 1919 big-league season ended, Treat ’em Rough added two active big-leaguers: Carl Mays (billed in one ad as “Yankee $15,000 Star17) and Rube Benton. On September 28, they pitched in another doubleheader against the Bacharach Giants. In the opener, Mays faced Dick Redding. Before a crowd estimated at almost 10,000, Mays lost when the Giants solved his submarine delivery for four runs in the 14th inning. Benton then fired a three-hit shutout in the second game.18 The following Sunday, Mays avenged his defeat with a five-hit, 1-0 shutout of the Bacharachs. Tesreau then made it a sweep, scattering 12 hits in a 4-3 win.19

Then, on October 14, the New York Giants (manager John McGraw may or may not have been running the club) returned to Dyckman Oval. However, not every man on the squad that day had actually been with the team in the regular season. The opponent was a team representing the Seabury shipyard, which was located in another nearby Bronx neighborhood, Morris Heights. Al Demaree and Red Causey held the Seabury squad to five hits as the Giants won, 10-1. George Burns led the attack with two singles and a double. Larry Doyle, Jay Kirke, and Joe Wilhoit each got two hits.20

The 1919 baseball season stretched into November at Dyckman Oval. With the semipro championship of Manhattan at stake, Treat ’em Rough faced the Lincoln Giants. a New York club whose ace pitcher was Smokey Joe Williams. Forming a battery with Williams was Louis Santop. Empey’s team had been reinforced by Burns, Doyle, and future Hall of Famer Frankie Frisch, then a New York Giants rookie. Close to 10,000 people packed in to watch Treat ’em Rough sweep the twin bill, 9-3 and 3-2. Joe Williams was shelled in the opener, giving up homers to Burns, Kavanagh, and Tesreau. Frisch went deep in the second game.21 At some point, Connie Savage (who’d become Treat ’em Rough’s manager) got hit in the head by a flying bat. He suffered a fractured skull but reportedly was not seriously hurt.22

Guy Empey formed a movie production company in 1919, writing and starring in his own films. Thus, Treat ’em Rough became Tesreau’s Bears in 1920. Jeff Tesreau (who was also coaching the Dartmouth College baseball team) retained Kavanagh for the Bears and added another ex-big-leaguer, middle infielder Joe Wagner. Behind the venture was the Ward Exhibition Company, which later assumed possession of the Oval. This entity, controlled by Eugene Ward and Irving Davis, was working in concert with Butterly. Additional stands were constructed.23

Tesreau pitched often and well for his Bears (and made more money than he ever had in the majors).24 In analyzing Tesreau’s semipro performance, Outsider Baseball author Scott Simkus offered an interesting observation about the Dyckman Oval diamond: it “had an awkwardly short center field fence, favoring the hitters.”25 Little other information is available about the Oval’s dimensions — but despite the lack of a detailed field diagram, a 1924 aerial photo does confirm what Simkus described.26

Tesreau’s Bears also launched the career of a future big-league pitcher. Curt Fullerton, who got into 115 games for the Boston Red Sox from 1921 through 1933, fired a no-hitter at Dyckman Oval on June 13, 1920.27

The Bacharach Giants played the Bears several times at the Oval in 1920. In one May doubleheader, shortstop Dick Lundy of the Giants starred both at bat and in the field.28 The two clubs might have played more often, but John Connor was holding out for 45% of the gate receipts and the Dyckman Oval officials did not want to pay more than 40%. The caliber of play pleased the local fans.

Other high-quality black squads visited the Oval to face the Bears in 1920. One was the Hilldale club from the Philadelphia area, starring Louis Santop.29 The Lincoln Giants also returned. Joe Williams and Jeff Tesreau squared off again on September 26; Tesreau was hit hard and the Bears lost, 9-5.30 A previous meeting, on Independence Day, had drawn such a big crowd that ground rules had to be put into force. Although Tesreau was unable to take the mound against Williams, the July 4 doubleheader pleased the fans so much that the return match was scheduled.31

Other baseball action at the Oval in 1920 involved the Rubber Industries Athletic League, representing six of the big tire companies then in existence. On Saturday, May 1, the United States Rubber Co., led by former big-leaguer Jack Kleinow, played Ajax, and Goodyear played Sterling.32

Big-leaguers were again visible at Dyckman Oval after the regular season had ended in 1920. An anonymous observer in the New York Evening Telegram wrote, “Many of the stars of the game are still unwilling to leave the vicinity of the Metropolis and the added incentive of picking up some pin money for the winter months is not to be sneezed at.” 33 On October 9, the New York Giants faced Joe Williams and the Lincoln Giants. Larry Doyle’s first-inning homer was the only run that “Cyclone Joe” (as he was also known) allowed in 11 innings. The hawknosed righty struck out 13 and walked just one. Pol Perritt, who’d rejoined New York late that season, took the loss after pitching six scoreless innings.34

A few days later, Carl Mays returned to the Oval leading a team that faced Tesreau’s Bears. Mays pitched the opener of a doubleheader, and starting the second game was Lefty O’Doul, then still a pitcher and a Yankees minor-leaguer.35

Earlier that October, Babe Ruth played in a doubleheader at the Oval against the Bears, receiving $1,000 for his services. Because he had given his word to appear there, he turned down an offer for $2,500 to join his fellow Yankees in a barnstorming game in New Haven, Connecticut.36 Joining the Babe on his squad were Mays and at least two other Yankees who didn’t go to New Haven, Bob McGraw and Fred “Bootnose” Hofmann.37 Ruth’s team won the first game easily, but the second game was a duel between Mays and Tom Godfrey, who struck out Ruth three times and earned a look from the Yankees during spring training 1921.38 The Bambino hit three homers altogether and also did “some clever pitching” in the 11-5, 6-5 sweep.39

Tesreau’s Bears also faced Alex Pómpez’s Cuban Stars, for whom the Oval was the closest thing to a home field, since Pómpez was competing with other clubs for dates.40 In one May 1921 game at the Oval between the Bears and the Cuban Stars, the Mayor of New York City, John F. Hylan, was on hand — though the ticket-taker did not recognize Hizzoner at first. Once Hylan entered, he went to the mound and threw four pitches, three of them strikes.41

Later that same month, Mayor Hylan was also the guest of honor when the soldiers’ teams from Fort Hamilton (Brooklyn) and Fort Slocum (on David’s Island in Long Island Sound) met at Dyckman Oval in a benefit game to aid the fund of the Washington Heights and Inwood Monument Association.42

Also in 1921, the Bacharach Giants played a series there against the Chicago American Giants. Dick Lundy starred again, and the games made an impression that lasted for years.43

In addition to baseball, boxing was staged at Dyckman Oval. Future heavyweight champion Gene Tunney won two bouts there in the summer of 1921, one on August 4 and another on September 26. Management spent $250,000 dollars to upgrade the facility into a permanent site for boxing, with the promise of another quarter-million in improvements. The dedication ceremony took place in April 1922, and at least for that year, the stadium was devoted exclusively to boxing.44The Academy Athletic Club, dominated by interests owning the Oval, put on the fights.45 As a result, Tesreau’s Bears disbanded and the players joined various other clubs.

That July brought news that James Butterly, a prominent figure in the Academy A.C., hoped to stage a fight at the Oval between reigning heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey and Harry “The Black Panther” Wills.46 For various reasons, however, the two fighters never did face each other.47

These sporting activities took place as an ongoing legal battle began. In 1921, the City of New York placed Inwood in turmoil by taking court action against numerous local property holders.48 Entanglement continued during the 1920s, clouding title to Dyckman Oval.

Amid the battle, the Eastern Colored League was formed in 1923 and lasted for what Pómpez’s biographer, Adrian Burgos, described as five tumultuous seasons.49 The Cuban Stars were in the ECL and called Dyckman Oval home. Yet despite the outstanding play of star outfielder Alejandro Oms, the Stars were at best a mediocre team.50

One thing may have helped the ECL, though: the June 1923 court decision that awarded title to the Oval to New York City, which was interested because baseball was a source of revenue. As Adrian Burgos put it, the decision “seemingly stripped off a layer of whom ECL owners had to work with to arrange games at the Oval.”51 The city had originally brought the suit in 1921 against the Northern Terminal Corporation and James Butterly. In the interim, because Ward and Davis had been unable to complete their purchase, the Oval had been sold to the Carnival Palace Corporation, which was not a party to the suit.52 Carnival was another corporate façade for Butterly (and silent partner Bernard Greene).

However, counsel for the losing parties immediately obtained a stay of the judgment pending appeal. Ownership of the Oval and other Dyckman properties remained in legal limbo for the next several years.53 This was a factor in the financial and management difficulties that plagued the facility at times.54

Making matters worse, the Great Depression hit in 1929. Yet sporting activity continued at the Oval. Soccer was the main sport, but cricket was also visible (in the past, ice skating competitions had been held as well). For example, in July 1930 the Cameroon Cricket Club of Brooklyn took on a visiting All-Star team.55

The New York Black Yankees played some games on Sundays at Dyckman Oval in the spring of 1932. But after a doubleheader against the Pittsburgh Crawfords on June 5, the Black Yankees severed their connections with the Oval. The team was losing money (it got none of the concession revenues) and thus broke its lease. Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson starred for the Crawfords in the second game of that last doubleheader.56

Late in 1934, Alex Pómpez reorganized the Cuban Stars as the New York Cubans and sought admission for the franchise into the Negro National League (NNL). Burgos noted that Pómpez’s activity as a “numbers banker” was not what concerned the NNL owners. The bigger issue was whether he had a viable ballpark under his control. Previously, the Stars had bounced around across the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and even Newark, New Jersey. Pómpez had support from the local black press, which fully expected him to upgrade Dyckman Oval. Sure enough, he took out a three-year lease on the Oval and spent $60,000 to erect fireproof stands, a clubhouse, and beer garden. The stadium’s capacity expanded to approximately 12,000 as 1935 approached.57 A 1937 aerial photo suggests that Pómpez also pushed out the outfield fences, most notably in left field.58

What’s more, Pómpez installed floodlights. Just days after the first big-league night game took place at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field that May 24, the transformed Oval was unveiled.59

That year, Pómpez assembled a powerful team, led by player-manager Martín Dihigo. The squad also boasted other excellent Cubans, including Oms, pitchers Ramón Bragaña and Luis E. Tiant (father of the future big-league star Luis C. Tiant), and Lázaro Salazar. The shortstop was a Dominican, noted gloveman Horacio “Rabbit” Martinez. U.S.-born players of African descent were also a big part of the roster.

The Cubans won the second half of the NNL season and thus faced the Pittsburgh Crawfords for the league championship. However, the Crawfords — led by Gibson and Charleston — defeated the Cubans in a hard-fought seven-game series that concluded at Dyckman Oval.

On September 29, 1935, the Cubans played the Babe Ruth All-Stars in a doubleheader at the Oval. The 40-year-old Bambino (whose big-league career had ended that May) reached Lefty Tiant for a double in the first inning of the opener. “But that was it!” wrote Negro League historian Larry Lester. “Tiant shut down the Babe Ruth All-Stars on four hits, as the Cubans won, 6-1.”60 Though Ruth was paid to play in just the first game, between games he put on an impressive show in batting practice, belting numerous balls out of the park.61

Pómpez also presented wrestling and boxing events. In fact, retired boxing champ Jack Dempsey refereed a wrestling match on June 13, 1935.62 On August 26, 1935, a bantamweight title fight took place at Dyckman Oval between Sixto Escobar of Puerto Rico (for whom San Juan’s Sixto Escobar Stadium would be renamed) and Lou Salica. The 15-round bout, won by Salica, was described as “one of the most savagely fought battles ever staged by little men in the New York area.” It took place before an estimated crowd of 15,000.63

Later boxing matches there featured Cubans Kid Chocolate and Kid Gavilán, as well as another Puerto Rican favorite, Pedro Montañez.64 The latter “rocketed from obscurity to fame through his bouts at the Oval.”65

American football was also played on the Inwood field. In the fall of 1935, early African-American gridiron star Fritz Pollard formed his New York Brown Bombers team, which “kept things lively at the Oval until late in November.”66 Pollard’s squad featured former NFL halfback Joe Lillard, who also played Negro League baseball. The Brown Bombers, who took the nickname of the great heavyweight boxer Joe Louis, returned in 1936 and 1937.

Adrian Burgos described the Dyckman Oval scene as “hopping.” It was a convenient location for Harlem’s sizable black population, well served by public transportation, and northern Manhattan had also become home to a large number of baseball-loving Latinos. Celebrities such as Joe Louis, track star Jesse Owens, and jazz pianist Fats Waller were often in the crowd, which impressed even the ballplayers. Burgos called the Oval “a unique cultural space that made Negro-league games distinct from major-league games. . .the ‘color’ and ‘spirit’ of the scene produced a sense of collectivity, pride, and affirmation.”67

The Cubans’ 1936 season started auspiciously with a matchup of Satchel Paige (whom Gus Greenlee had lured back to the Pittsburgh Crawfords) and wily Chet Brewer.68 Satch struck out 12 in the opener, and Josh Gibson hit three homers in the twin bill, which Pittsburgh swept, 8-4 and 6-5.69 That summer, however, special prosecutor Thomas Dewey set his sights on Pómpez for involvement with the numbers racket in New York. “Late in the season, the Cuban absented himself from his park and remained away through the [1937] season.”70

The Cubans did not operate during either 1937 or 1938. However, the New York Black Yankees moved back into Dyckman Oval in 1937. Unfortunately, “James Semler, their owner, lacked Pómpez’s vision and ability and 1937 was a failure. The lease having expired, the stands were demolished and the property taken over for other purposes.”71

The last sporting event at Dyckman Oval may have been the New York Brown Bombers’ game on November 24, 1937.72 By April 1938, the lot had been completely razed; only a few cars were parked where the stands had been. The site was apparently used that summer for a tourist camp. There was talk that Pómpez would buy an adjoining city block and build a new Dyckman Oval to host Negro League ball.73 Various articles from the summer of 1938 do in fact refer to a “New Dyckman Oval,” which appears to have been a smaller boxing venue slightly south of the stadium. After the New York Cubans returned to the NNL in 1939, they played some occasional home games in Yankee Stadium and, in 1943, some in the Polo Grounds. They did not have a true home field again until June 1944, when Pómpez secured a lease to play in the Polo Grounds.

The New Dyckman Oval was short-lived. During the early ’40s, the Speedway Gardens came to the same address, 31 Dyckman Street. It may simply have been the same facility with a different name. Among other things, it hosted live jazz and horse shows.

In December 1948, development of the Dyckman Houses began on the old stadium site.74 This public housing project was completed in 1951 and still stands. Its most famous former resident is NBA superstar Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, known as Lew Alcindor when he grew up there.

As it is, no plaque commemorates the existence of Dyckman Oval, yet it lives on in New York City history. At its peak in 1935, the “beautiful miniature stadium” had a rightful claim to “the title of Manhattan’s amusement center.”75

Acknowledgments

This story was originally published in 2018 and was updated in August 2020. It was edited by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Alan Cohen. Continued thanks to Eric Costello and Bill Lamb. Their legal training and knowledge of New York history provided much insight. Additional thanks to Donald Rice for further input that prompted the update.

Sources

Photo credit: Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society.

Cole Thompson, “The Dyckman Oval,” My Inwood website (http://myinwood.net/the-dyckman-oval/). This history includes numerous clippings and pictures.

Fultonhistory.com — online archive of New York State newspapers. Where page numbers are not shown in the notes below, they were either missing or illegible.

Butterly v. Maribert Realty Corp., 234 App. Div. 424, 255 N.Y.S. 321 (1st Dept, 1932), aff’d 260 N.Y. 559, 184 N.E. 89 (1932). (https://books.google.com)

1918 Grand Central Red Caps — calendar including newspaper clipppings (http://negroleagues.bravehost.com/adb.html)

1919 Bacharach Giants — calendar including newspaper clippings (http://negroleagues.bravehost.com/abs.html)

1919 Chicago American Giants — Calendar including newspaper clippings (http://negroleagues.bravehost.com/abp.html)

1920 Bacharach Giants — calendar including newspaper clippings (http://negroleagues.bravehost.com/aaj.html)

Boxrec.com

Notes

1 William E. Clark, “The Sports Parade,” New York Age, April 2, 1938: 8.

2 “City Suit Involves Millions in Realty,” New York Times, June 10, 1923: Editorial-2.

3 E-mail from Bill Lamb to Rory Costello, July 8, 2018.

4 “Semi-pros in Four Big Games To-day,” New York Press, April 25, 1915: 5.

5 “Four Big Games on Local Diamonds,” New York Press, May 23, 1915: 28.

6 “Dyckman Ovel Fenced,” New York Sun, April 12, 1917: 14.

7 “Egan’s Fall Costly; Bushwicks Lose Game,” Brooklyn Standard Union, July 2, 1917: 6.

8 “Marquard Heeds Warning,” Troy Times, October 22, 1917: 5.

9 “Kingsbridge Athletics Sign Zimmerman,” New York Evening World, August 31, 1918.

10 “Polo Giants Beat Lincoln Giants,” New York Herald, October 28, 1918: 8.

11 “Doyle on Rampage with Bat,” New York Herald, November 4, 1918: 10.

12 “Giants Play for War Fund,” New York Sun, November 9, 1918: 11.

13 James E. Overmyer, Black Ball and the Boardwalk, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2014: 63-64.

14 “‘Treat ’em Roughs’ Debut,” New York Sun, May 11, 1919: 5.

15 “Tesreau Outpitches Dick Redding,” New York Age, August 9, 1919: 6.

16 “Chicago American Giants in Series at Dyckman Oval,” Brooklyn Standard Union, August 15, 1919: 5.

17 New York Evening Telegram, September 27, 1919: 6.

18 “Mays Loses in 14th,” New York Sun, September 29, 1919: 16.

19 “Mays Avenges Defeat,” New York Sun, October 6, 1919: 21.

20 “Giants Defeat Shippers,” Troy Times, October 14, 1919.

21 “Semi-pro Title Won by Empey’s Team,” New York Sun, November 10, 1919: 20..

22 :Connie Savage Injured,” New York Sun, November 10, 1919: 20.

23 “Jeff Tesreau to Manage Strong Independent Team,” Harrisburg Telegraph, March 6, 1920, 12. Unfortunately, the before and after numbers for seating capacity in this article are not legible.

24 “Sports Comment,” Harrisburg Evening News, January 20, 1922: 22.

25 Scott Simkus, Outsider Baseball, Chicago: Chicago Review Press (2014): 131.

26 New York Public Library Digital Collections (https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e2-f6d8-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99)

27 “Fullerton Pitches No-Hit Game for Tesreau’s Bears,” New York Tribune, June 14, 1920: 10.

28 Ted Hooks, “Lundy and Cuban Strengthen Bacharach Giants — They Win,” New York Age, May 15, 1920: 6.

29 “Tesreau’s Bears Play Hilldale Nine To-Day,” New York Tribune, July 25, 1920: 15.“Hilldale Breaks Even with Tesreau’s Bears,” New York Age, September 4, 1920: 7.

30 “Lincoln Giants Win Twice from Jeff Tesreau’s Bears,” New York Evening Telegram, September 27, 1920: 7.

31 “Lincoln Giants Again to Meet Tesreau’s Bears,” New York Evening Telegram, September 22, 1920.

32 “Tire Men Cross Bats in Opening Games,” Motor World, May 5, 1920: 45.

33 “Baseball Still in Bloom Up at Dyckman Oval,” New York Evening Telegram, October 14, 1920: 6.

34 “Williams, Negro Hurler, Fans 13 of N.Y. Giants,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 10, 1920: 64.

35 “Baseball Still in Bloom Up at Dyckman Oval.”

36 “Offered ‘Babe’ Ruth $2,500 for Single Ball Game,” Amsterdam (New York) Evening Recorder, October 5, 1920: 8.

37 “Ruth and His Nine to Visit Dyckman Oval,” New York Tribune, October 2, 1920: 12.

38 “News of the Nearby Towns,” Mount Vernon (New York) Daily Argus, October 5, 1920. “Yankees Buy Four Players,” New York Tribune, December 23, 1920: 12.

39 “Ruth Hits Three Homers,” Brooklyn Standard Union, October 4, 1920.

40 Burgos, Cuban Star: 47.

41 “Mayor Pitches Ball, ‘Fans’ Cuban Slugger: His Honor Visits Dyckman Oval and Makes Good as a Twirler,” New York Times, May 9, 1921.

42 “Hylan to Be at Game,” New York Times, May 14, 1921: 16.

43 Clark, “The Sports Parade.”

44 “Dyckman Oval to Stage Boxing Exclusively,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 19, 1922: 27. “To Stage Fistics at Dyckman Oval,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, April 22, 1922: 8.

45 “Forty Rounds Tonight at Dyckman,” Yonkers Statesman and News, May 22, 1922: 9.

46 “First Offer Made for Dempsey-Wills Bout,” New York Times, July 14, 1922, 17.

47 Sean Crose, “Dempsey vs Wills: The Superfight That Never Was,” The Fight City website, December 21, 2017 (https://www.thefightcity.com/dempsey-vs-wills-boxing-history-jack-dempsey-harry-wills/)

48 The litigation was likely prompted by problems over the diversion of nearby Sherman Creek and the construction of a new power plant on the reclaimed land. Butterly, in particular, had been an irritant to city officials, suing for $1 million in damages that he alleged the power plant had caused to his property.

49 Burgos, Cuban Star: 47.

50 John Struth, “Alejandro Oms,” SABR BioProject (https://sabr.org/node/28415)

51 Burgos, Cuban Star: 49.

52 “City Suit Involves Millions in Realty.”

53 In 1925, the Appellate Division reversed the 1923 decision and ordered a new trial. On retrial two years later, the Dyckman property owners prevailed. But their title to the contested properties was not quieted until the retrial outcome was affirmed by the Appellate Division and leave to appeal by the City was denied by New York’s highest court (the Court of Appeals) in October 1928. By that time, the Dyckman Oval had been placed at the center of litigation brought against Butterly by the Oval’s mortgage holders.

54 Back in 1921, the institution of the City’s lawsuit had prompted Butterly’s dummy corporations to discontinue paying both city taxes on the Oval and interest on the Oval’s mortgage. This was another facet of the complex ongoing legal actions involving the property.

55 “Can They Make It?”, New York Amsterdam News, July 16, 1930.

56 “Black Yankees Quit Dyckman Oval,” New York Age, June 11, 1932: 6.

57 Burgos, Cuban Star: 82-83, 86. Clark, “The Sports Parade.” It’s unclear who granted Pómpez the lease, and why he would risk losing $60,000 in improving property that he did not own and whose lease might have been granted him by a party that the courts could later deem a non-owner.

58 Photo from Donald Rice collection, originally part of the NYC Parks Olmsted Center records of the opening of Fort Tryon Park or the Cloisters.

59 Burgos, Cuban Star, 88. By some accounts, Dyckman Oval’s lights were installed in 1930, but the timing of Pómpez’s lease implies that 1935 is the correct date.

60 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press (2001): 64.

61 Leigh Montville, The Big Bam, New York: Random House (2006): 563.

62 “Jack Dempsey,” New York Amsterdam News, June 8, 1935.

63 Cole Thompson, “El Gallito: 1935 Sixto Escobar Fight in the Dyckman Oval,” My Inwood website, April 28, 2015. (http://myinwood.net/el-gallito-1935-sixto-escobar-fight-in-the-dyckman-oval/). Quote drawn from the Pittsburgh Post Gazette, August 27, 1935.

64 Burgos, Cuban Star: 86.

65 Clark, “The Sports Parade.”

66 Ibid.

67 Burgos, Cuban Star: 85-87.

68 “‘Satchel’ Paige vs. Brewer at Opener,” New York Age, May 9, 1936: 9.

69 Lewis Dial, “The Sport Dial,” New York Age, May 16, 1935: 9.

70 Clark, “The Sports Parade.”

71 Ibid.

72 “Bombers Nosed Out,” New York Daily Worker, November 26, 1937.

73 Clark, “The Sports Parade.”

74 “New Dyckman Houses to Get First Tenants,” New York Post, September 26, 1950.

75 Lewis Dial, “The Sport Dial,” New York Age, August 24, 1935: 8.