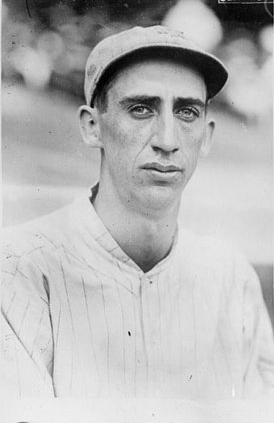

Poll Perritt

Given a comical nickname based on his last name and beaky nose, William Dayton “Poll” Perritt had a successful 10-year pitching career, pitched in a World Series, was bribed by Hal Chase, tussled with John McGraw and oil barons, and became a modestly successful Louisiana oilman.

Given a comical nickname based on his last name and beaky nose, William Dayton “Poll” Perritt had a successful 10-year pitching career, pitched in a World Series, was bribed by Hal Chase, tussled with John McGraw and oil barons, and became a modestly successful Louisiana oilman.

William Dayton Perritt was the first child born to William Thomas Perritt, a farmer, and Hanie (Walker) Perritt on August 30, 1891, in Arcadia, Louisiana. Hanie’s great-grandfather, Rev. Sanders Walker, was a Revolutionary War chaplain. William Thomas Perritt was the first son of Madison Perritt, who served with Company B of the 12th Louisiana Infantry during the Civil War, and his grandfather fought in the Seminole War.1 William and Hanie had four children. Hanie died in 1909; William soon married Kate Willet, an Alabama native. William and Kate had six more children together.

Dayton (as the youngster was known to distinguish him from his father2) played baseball on area sandlots. He learned the game from his uncle, Madison Floyd Perritt, who was about seven years older than Dayton and pitched in the Texas and Pacific Coast Leagues, among other stops. Madison’s nickname was also Poll. The first mention of Dayton Perritt came in 1908 when he was the winning pitcher for Arcadia. Perritt had multiple interests — he sang in a quartet.3 He was also a runner, long jumper, and pole vaulter on his high-school track team.4

Uncle Madison got Dayton tryouts with local baseball teams. Perritt pitched semipro ball for Homer and Minden in Louisiana prior to his jump into professional baseball.5 In 1912 Vicksburg of the Cotton States League signed Perritt. That spring he faced Wild Bill Donovan in an exhibition game when the Detroit Tigers toured Mississippi during spring training.6

At first, Perritt was a hesitant fielder. In an early game against New Orleans, the bases were loaded when the batter hit the ball to him. Instead of throwing home, he froze and let the runner score. At some point he realized he had to throw the ball somewhere and got the out at first.7 A week later, pitching to a catcher whose last name was PARROTT, Perritt earned his first win over Jackson.8 Such heady days pitching for Vicksburg would be few. He again blanked when fielding a squeeze bunt and failed to throw the ball to any base. After that game, Vicksburg released Perritt.9

Fortunately for Perritt, his best outings were against Greenwood in the same league. Greenwood lacked pitching; Perritt got a second chance. On May 20 he pitched both ends of a doubleheader against Vicksburg, winning and losing one.10 Perritt became the Joy Riders’ ace. By late summer the Cotton States League disbanded.11 Cardinals scout Bill Armour saw the lanky ace pitch and persuaded Perritt to come north with him to St. Louis.12

On September 7, 1912, Perritt was still in his first professional season of baseball when St. Louis manager Roger Bresnahan called on him in the fifth inning to replace starter Sandy Burk. Perritt ended the frame with his first career strikeout victim: Honus Wagner.

Writers noticed that Perritt looked like the left-handed Harry “Slim” Sallee, another pitcher with an alliterative handle and obvious nickname. Both were tall and lanky with drooping shoulders — they even pitched similarly, except that Perritt threw with his right hand and Sallee was a southpaw.13 The next season they were roommates and became best of friends.14

Perritt closed the season beating Cincinnati by retiring the last nine batters for his first major-league victory.15

Miller Huggins managed the Cardinals in 1913 and gave Perritt a chance to join the rotation. Thankfully, he was very patient. Huggins got perhaps two good outings a month from Perritt, enough to keep his job while learning the ropes. And Perritt had lots to learn. He still got lost fielding the ball with men on base. He needed to learn to pitch from the stretch to keep runners close, he needed to stay ahead of hitters, and he needed to master a breaking pitch.16

Lessons from Sallee and Huggins kicked in during Perritt’s last three outings. He went 10 innings before losing to Philadelphia’s Pete Alexander, 2-0. He next lost to Boston but allowed just two runs and five hits. In his last start, he held the Reds to two runs on six hits and got the win. He finished with a 5.27 ERA and a 6-14 record. Still — he kept a job all season.

Then Perritt mingled with Joe Tinker, who was to manage the Chicago Whales of the Federal League, and used that to get a raise out of the Cardinals for 1914.17

The 1914 Cardinals were in contention for the pennant and Perritt had a number of excellent outings from the start. Soon he was the subject of rumors saying he would leave the Cardinals and join the Federal League. Rebel Oakes managed Pittsburgh in the Federal League. Being from Lisbon, Louisiana (only about 20 miles north of Arcadia), Oakes had known Perritt for years.18

Perritt also became the subject of poetry. St. Louis sportswriter Billy Murphy wrote a poem based on Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” and tied to Perritt’s recent success over the Robins and the Robins’ losing streak. In this poem, manager Wilbert Robinson had a “grewsome” dream. Here’s an edited passage:

Last night while I pondered, dreary grouchy and very weary

Over Wednesday’s wretched battle far up on the seventh floor …

Open then I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter,

In there stepped a lengthy Perritt (Perritts always are a bore).Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he;

But with mien of lord or lady, perched above my hotel door,

On a photograph of Rucker, hanging o’er my hotel door.

Perched and sat — and nothing more.“Perritt,” cried I, “thing of evil, Perritt you’re a pitching devil”;

Whether Huggins sent or Britton cast thee here ashore.

Desolate, yet still undaunted, will you leave us, disenchanted,

Our poor team by hoodoo haunted, tell me quickly, I implore.Are we going to win today? Tell me for I’m getting sore.”

Quoth Poll Perritt: “Never more.”19

Murphy’s use of “Poll” as a nickname for Perritt was not the first time Dayton Perritt was given a “parrot-esque” nickname — Polly was in use by the time Perritt signed with Greenwood by 1912.20 A scan of digital newspapers will give you hundreds of results for Polly Perritt, Poll Perritt or Pol Perritt; they were used interchangeably. And the nickname was shared among Dayton Perritt, his uncle Madison Perritt, and an Olin Perritt who played in the minors when Dayton was getting his career started. Of the three nicknames, Poll was used the most frequently in Missouri, New York, and Louisiana newspapers between 1912 and 1921, when Perritt was an active player — about 50 percent more often than Pol.21 For that reason, Poll is used here.

Perritt got along with most people but was generally quiet and kept to himself. He was closest to his younger brother, Henry, and his road roommate (and doppelganger), Slim Sallee. During the season Sallee and Perritt were inseparable. Sallee talked pitching with Perritt and Perritt took his advice. According to a Cardinals scribe, Perritt and Sallee “take their strolls together, read together, eat together, and sleep together.”22 In the offseason, Dayton and Henry worked at a bank in Louisiana. Perritt loved cars — he drove a Metz roadster and later an Oldsmobile … quickly.23 But for the most part, he didn’t make waves.

Except when it came to his contracts. The Cardinals offered Perritt a three-year deal at $4,000 a year but Perritt didn’t sign. So the Cardinals privately told people he was drinking and complained about Perritt’s play or effort.24 Oakes made progress with Perritt, and though Perritt claimed he would be loyal to the Cardinals,25 he jumped the team the very day he received a bonus check from the Cardinals for their third-place finish. Immediately Cardinals President Schuyler Britton stopped payment on his check. Perritt and Britton met and had a heated exchange and Britton dared Perritt to sue.26 So Perritt hired a lawyer and filed a claim with the National Commission.27

Miller Huggins wasn’t going to lose his pitcher without a fight. Huggins “traded” Perritt’s rights to the Giants, who made Perritt a better offer than what Oakes offered. John McGraw offered to trade a player back to the Cardinals once he signed Perritt to a valid contract.28

When Oakes heard that, he met Perritt at a café in St. Louis. Perritt turned combative with his friend. He knocked Oakes out of his chair “and sent him sprawling into the aisle.”29 McGraw signed Perritt to a three-year deal. Writers who watched the war between the Federal League and the other two major leagues noted how Perritt’s contract-jumping showed that the reserve clause that kept players locked to a team was a farce. Here, the Cardinals used Perritt’s rights to block a player from leaving on his own terms, which failed, rather than take the player to court. And it allowed another manager to chase a player down to offer him a different contract to jump again away from his Federal League obligations.30

McGraw and Huggins spent the spring arguing about their “trade” for Perritt. Huggins wanted Bob Bescher; McGraw countered with Walter Holke, Fred Snodgrass, or Fred Merkle. No Giants player wanted to play in St. Louis.31 Bescher wanted a raise if he got traded and also wanted the Cardinals to pay him whatever bonus Giants players received for winning the pennant.32 Eventually, though, Bescher relented and joined the Cardinals for 1915.

Perritt couldn’t have made a worse first impression with the Giants. Each of his first three starts was poorer than the previous one. Then, before the May 1 game with Philadelphia, he was shagging flies when he accidentally collided head-to-head with Phillies third baseman Bobby Byrne. Perritt suffered a broken nose, cuts near both eyes, and the loss of three teeth.33

Yet Perritt took the mound just 12 days later to beat the Reds for his first win.34 That was his lone highlight, however, and the Giants fell to last place. McGraw grew feisty. He allegedly offered to send Perritt back to St. Louis for nothing if Huggins would take on Perritt’s three-year, nearly $20,000 contract.35 Perritt finally found his form in June. In July, he got revenge against the Cardinals by winning game one of a doubleheader in relief and then shutting them out in the second game.36 The Giants made it back to .500 before a rash of doubleheaders wore out the team. The Giants returned to last place and Perritt finished 12-18; his 12 wins were second behind the 19 of his future brother-in-law, Jeff Tesreau.

Tesreau and his wife, Helena, invited Perritt to their home for dinners. Occasionally, Helena invited her sister, Florence Pauline Blake, to join them. Later, Dayton took Florence out for rides in his car and they frequently exchanged letters. Jerome Beatty of the New York Tribune wrote, “When the Giants were on the road Poll’s morning rush to look over the mail was so impulsive that in a St. Louis hotel it was said he almost killed a suspender salesman who was so unfortunate as to stand between Poll and a letter.”37 That October, Perritt pitched his Giants to a win over the Lincoln Negro Giants in an exhibition, then drove to the Church of the Annunciation and married Florence.38

Perritt suffered one more baseball loss in 1915 — his 1914 bonus claim. The National Commission ruled against him, saying he couldn’t ask for a supplementary portion of a contract he himself had breached (meaning the reserve clause) by not staying with the Cardinals.39

The 1916 season started differently for Perritt. McGraw didn’t use him much — there were other options and Perritt was rarely good in the cold days of April and early May. When given his chance, Perritt won four straight decisions in May. And the Giants, after opening the season 2-13, got hot with him. New York won 17 straight games to close on first-place Brooklyn. Perritt was edgier in July until he learned his first daughter, Florence Rose, was born and everybody was healthy and happy. That same day, the Giants traded Christy Mathewson to the Reds, where Matty became the manager — which meant regular duty for Perritt the rest of the season.40 Poll won eight of his last 11 decisions.

Two wins came on September 9, when Perritt won both ends of a doubleheader to beat the Phillies, winning 3-1 in the opener and 3-0 in game two. Brooklyn moved into first place, dropping the Phillies into second.41 On a roll, the Giants won 26 of 27 games (with one tie) to roar into third place as October began with only a four-game series left with Brooklyn.

On October 2 Brooklyn held a half-game lead over the Phillies, who finished with a series against Boston. Wilbert Robinson, John McGraw’s best friend in baseball, managed the Robins. In prior years, teams alleged that McGraw got help from former players and teammates who now managed other teams and allegedly lost games to help the Giants win pennants. Would McGraw return the favor to Robinson? In the first game of their series, McGraw started relative newcomer Ferdie Schupp, who won the ERA crown with a 0.90 ERA in 140 innings. Schupp was good, but Art Fletcher stumbled fielding a grounder by Jake Daubert, allowing Daubert to reach. Daubert took off for second and the catcher’s throw got to second base in time — but Buck Herzog dropped the throw. Zack Wheat singled and the Robins held on to win.42

Meanwhile, Boston wouldn’t sit down for the Phillies. Two Boston players suffered broken arms when hit by pitches thrown by Philadelphia pitchers.43 The Braves and Phillies split a doubleheader, extending the Robins’ lead to a full game.

The next day, the Giants — who were brilliant in games heading into this series — played the ugliest game possible. Despite sloppy baserunning, the Giants held a 4-1 lead, but pitcher Rube Benton couldn’t hold it and almost immediately was pulled in favor of Perritt.

Perritt got little help, too. Players dropped the ball or delayed making throws. At some point, Perritt started contributing to the sloppy play with a horribly bad throw, a really wild pitch, and long windups with runners on base. Perritt’s biggest blunder came after getting a base hit. With McGraw coaching third base, Perritt inexplicably stopped halfway between second and third on George Burns’s single to right. Perritt was thrown out by a mile.44

If McGraw intended to throw another game to his friend, he certainly didn’t expect to see it happen like this. A successful sacrifice bunt with runners on first and second turned into a 1-3-6-8-2 double play when the runner on second, Dave Robertson, continued to third base — which was already occupied. McGraw got angriest with Perritt, screaming obscenities and leaving the field after Perritt allowed a runner to steal a base. Then McGraw told the press he was done for the season and his players had quit on him during the game.45

The Phillies didn’t help themselves. In a second doubleheader, they lost both games to Boston. With two games left for both teams, the Phillies now trailed by 2½ games and Brooklyn claimed the pennant.

Still, something stunk, and it wasn’t just the way the Giants played. People accused Perritt of laying down. “If there is any implication that I helped to lose the game you can give it the lie for me,” said Perritt. “That game cost me the $100 I had bet that I would win 20 games. I was out to win.” (Papers showed Perritt had a 19-10 record, though official statistics had him with 18.)46

McGraw’s calling out his players for quitting angered his players and especially Wilbert Robinson. Wilbert said McGraw’s accusation was unsportsmanlike and unfair, as his team had won the majority of contests between the two teams during the season. And he claimed his Robins were the best team in the league for 1916.47

League administrators held an informal meeting that night and exonerated the Giants, saying the league would take no action.48 No matter what, the way the Giants crashed before the Robins came out as unfair to Philadelphia; the Giants should have done more to play smarter and harder until the final out. Instead, as Grantland Rice noted, one of the best pennant races wound up being an embarrassment to baseball.49

With the long winning streak to close the season, the Giants were favored to win the pennant in 1917. Perritt began the season as he had in previous years. McGraw didn’t use him much in the first few weeks. And he missed time with an illness in early June.50

Then, for almost four months, Perritt was brilliant. His ERA from June 14 through the end of the 1917 season was 1.47. Perritt finished 17-7 with a 1.88 ERA — second on the team in ERA, third in wins. As predicted, the Giants won the pennant and faced the White Sox in the World Series. Because the White Sox featured so many good left-handed batters — like Shoeless Joe Jackson and Eddie Collins — Perritt saw little action. The Giants gave all starts to southpaws Schupp, Sallee, and Benton. Perritt pitched three times in relief as the White Sox dispatched the Giants in six games. He also got hits in both of his at-bats.

Perritt reached his peak — a pretty good pitcher, very good on his best days — and relatively durable for the last five seasons. Yet some in the New York press complained that he should have been better — almost blaming his Southern heritage for his failings. W.J. Macbeth said Perritt should have taken his profession more seriously, and “(i)t would be wrong to accuse him of laziness just because he was born and raised in Arcadia, La., where the sun scorches out ambition and the hookworm runs rampant.”51

Having won a pennant, many of the Giants looked for a raise. One, naturally, was Poll Perritt. He was among the last to sign his contract for 1918.

It was a rough year for the Giants. Perritt was the only starter to regularly pitch in the war-shortened 1918 season. He started the season like an ace, winning 12 of 14 decisions and throwing four shutouts by Independence Day. But something changed on July Fourth. He went into a seven-week slump in which his ERA was double that of the previous three months. He might have been overworked while everyone else was unavailable. The Giants’ season went much the same way — starting the season 18-2 and then playing .500 ball until the Cubs took the pennant. Perritt finished the season at 18-13, pitching 233 innings, though the team played essentially 75 percent of a full season (World War I brought an early halt).

As the 1918 summer wound down, Cincinnati came into town and played the Giants in a doubleheader on July 17. While Perritt started tossing a ball around, Reds first baseman Hal Chase stopped by with a proposition. He asked Perritt which game of the doubleheader he would be pitching. Chase added, “I wish you’d tip me off, because if I know which game you will pitch and can connect with a certain party before game time, you will have nothing to fear.”52 (Later it was suggested that Chase offered Perritt $800 to throw the game.53) Perritt told McGraw about it and said he was so bothered by it he should have punched Chase.54 Later, in his official affidavit, Perritt added that he told McGraw it was about time players got together and got Chase out of the game for good.55 As for his pitching, Perritt was especially miffed when his wild pitch allowed what turned into the winning run in the fifth inning of a 2-1 loss to the Reds.56

Three weeks later, Chase was suspended by Reds manager Christy Mathewson for “indifferent playing.”57 Chase took up his suspension with the National Commission and a hearing was held in New York. However, many of the players who were to be witnesses at the hearing failed to attend. Mathewson was in Europe fighting for the Allies. McGraw was out of town and Perritt was busy in Louisiana with his new job.58 When league President John Heydler handed down his decision, Macbeth wrote, “it is nowhere established that the accused was interested in any pool or wager that caused any game of ball to result otherwise than on its merits.” Heydler found there wasn’t enough evidence to convict Chase.59

McGraw was later quoted as saying he thought the case against Chase was weak even though he testified against him.60 He signed Chase to play for the Giants in 1919.61

That offseason, Dayton and Henry Perritt became oilmen, investing money in nearby land and oil derricks. Poll reached out to current and former teammates and other baseball men to encourage them to invest in Louisiana oil country — including Rebel Oakes and one-time Federal League team owner Harry Sinclair,62 who became a major oil producer in the area. Poll Perritt became W.D. Perritt, a director for the Bird Brothers Oil Company.63

Perritt saw that he could acquire wealth in a way he couldn’t with the Giants. And McGraw, with whom he had an occasionally contentious relationship, signed the very player who offered Perritt a bribe in 1918. So he turned down his 1919 New York Giants contract.64 Instead, Perritt signed leases on thousands of acres of land and started sinking wells.65 Perritt didn’t avoid baseball — he ran the semipro team in Homer and pitched a few innings.66 Eventually he decided he needed a regular paycheck and in May, while trying to find other investors in his oil company, he visited McGraw in New York City and signed a Giants contract.67

Having missed spring training, Perritt couldn’t get into playing shape and lost the break on his curveball.68 Later, he claimed his forearm was sore trying to get in shape too quickly and though he tried visiting an osteopath, it didn’t work.69 In August he was allowed to leave the team to pitch semipro games in hopes he would regain his form. That club, known as “Treat ’em Rough,” played at Dyckman Oval in far northern Manhattan. It featured numerous former big leaguers, notably Jeff Tesreau. Perritt once faced Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants — featuring Oscar Charleston, Bingo DeMoss, Cristobal Torriente and others — and lost the second game of a doubleheader.70

After the season, Perritt fought with his Giants teammates for money. When postseason bonuses were paid, Giants players didn’t vote him a share. Perritt — who never ducked a chance to make more cash — threatened to go to the National Commission for his share. He instead compromised with his teammates and took a half-share, though he had pitched only 19 innings for the Giants in 1919.71

Perritt went back to his oil business, occasionally pitching semipro ball in the summer of 1920. The Giants allowed him to sign with San Antonio in the Texas League; if he pitched well, they could recall his rights. Perritt won two decisions, then joined the Giants in late August and made eight appearances.72 He joined the club for a tour of Cuba that October.73 He then agreed to come back to the Giants in spring training for 1921.74

Perritt’s 1921 season was his last. The Giants released him in May.75 The Detroit Tigers signed the veteran but released him in early July after just four outings.76 His big-league career ended with a 92-78 record and 543 strikeouts in 1456⅔ innings.

Ty Cobb recommended Perritt to the Minneapolis Millers.77 The Millers sent Perritt, who wasn’t in shape, to St. Joseph in the Western Association. Perritt quickly came to dominate that circuit and returned to the Millers to finish the season. In his last game with St. Joseph, he homered during a ninth-inning winning rally.78 When he rejoined Minneapolis, he hit an inside-the-park homer over the head of St. Paul’s Bruno Haas.79 But on the mound, Perritt was, at best, tolerably effective in the American Association. Thus, his pro career ended.

W.D. Perritt’s life as an oil baron played out like episodes of a modern television drama. He acquired land leases and drilled for oil.80 In the good years his oil wells generated moderate wealth. In bad years, wells built on land he leased failed to hit oil and he was sued to pay debts. Once he got in a fight with a neighbor, Paul Miller, because Miller built a fence to keep Perritt’s daughters from stomping over Miller’s vegetable garden.81

In 1934, the pitcher — known for being a “temperamental cuss”82 — fought with his good friend Dick Sebastian over a loan. Perritt entered Sebastian’s hotel room where Sebastian had been enjoying dinner with two female friends. When they started quarreling over money, Sebastian pulled out a .22-caliber pistol and shot Perritt in the hip. That didn’t stop Perritt — they continued to brawl and when police arrived, Perritt was on top of Sebastian.83

Both daughters, Florence and Helen, moved to New York and stayed in the Northeast. Florence, Perritt’s wife, died while visiting Florence, their daughter, in Massachusetts in 1944.84 The younger Florence went to business school and took a job with Continental Can, where she’d meet her husband. She died in 2008.85 Helen became a social worker and died in 1987.86

Perritt’s brother, Henry Walker Perritt, remained in the oil industry (and active in local politics) until he died in 1990.87 William Thomas Perritt outlived his first son, dying in 1955.88 William Dayton Perritt fell ill in 1947 and died in Shreveport, Louisiana, on October 15, 1947.89

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

Baseball-Reference.com

baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=perrit001wil

Retrosheet.com

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/P/Pperrp101.htm

(Also, related linked pages that display his daily details or team game logs)

FindaGrave.com

findagrave.com/memorial/22394/pol-perritt (William Dayton Perritt)

findagrave.com/memorial/70881989/william-thomas-perritt (William Thomas Perritt)

findagrave.com/memorial/70881904/hanie-perritt (Haney Walker Perritt)

findagrave.com/memorial/48861294/henry-clay-walker (Henry Clay Walker)

findagrave.com/memorial/90940710/kate-perritt (Kate Willet Perritt)

findagrave.com/memorial/70881455/madison-perritt (Madison Perritt)

findagrave.com/memorial/115099349 (William Perritt)

findagrave.com/memorial/115099274/jane-perritt (Jane Loyd Perritt)

1830-1880, 1900-1940 US Censuses

Louisiana and New York Marriage Indexes

1920 US Passport Application

Military Headstone Application

Social Security Application

World War II Draft Registration Card

Louisiana Death Index

Biography of Madison and Amanda Perritt, transcribed from Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northwest Louisiana (Chicago and Nashville: Southern Publishing Company) and posted to Ancestry.com on February 10, 2016 by Walt Perro.

Notes

1 “Pioneer Citizen Drops Dead at His Home,” Shreveport Times, July 10, 1919.

2 “The Gibbsland Quartet,” Shreveport Times, April 22, 1909: 4.

3 “Sextette of Towns,” Shreveport Journal, April 14, 1909: 8.

4 “High School Field Exercises Today,” Shreveport Times, April 16, 1909: 6.

5 W.J. Macbeth, “Perritt on Edge for Big Series with White Sox,” New York Tribune, September 16, 1917, Sporting Section: 4.

6 “Vix. Makes Good Showing in Clash with Tigers,” Vicksburg (Mississippi) Evening Post, April 1, 1912: 5.

7 “Pels Romped on Hill Bills,” Vicksburg Evening Post, April 13, 1912: 3.

8 “Jackson Beaten by Vicksburg Team,” New Orleans Times-Democrat, April 20, 1912: 10.

9 “Perritt and Hooks Canned,” Vicksburg Evening Post, April 26, 1912: 3.

10 “Double Bill Split on Greenwood Lot,” New Orleans Times-Democrat, May 21, 1912: 10.

11 “Cotton States Closes,” Natchez (Mississippi) Democrat, August 29, 1912: 2.

12 “‘Come Back’ Rally Again Helps Cardinals Rout Ambitious Reds,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 1, 1912: 15.

13 Billy Murphy, “Perritt One Pitcher Who Has Never Received Credit for Brilliant Work in Box,” St. Louis Star, August 21, 1914: 7.

14 “Sallee Comes to Town to Visit Polly Perritt,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 28, 1914: 7.

15 “‘Come Back’ Rally Again Helps Cardinals Rout Ambitious Reds.”

16 “Hunt Tosses One Away by His Wildness, 6-1,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 20, 1913: Sports, 1.

17 “Cardinals Beat Feds to Pitcher Perritt,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 27, 1914: 6.

18 “Cards Continue Conquest of East by Toppling Phillies; ‘Poll’ Perritt Plucks Plum,” St. Louis Star, June 17, 1914: 9.

19 Billy Murphy, “The Perritt,” St. Louis Star, July 23, 1914: 11.

20 “Two New Pitchers Signed by Joyriders,” Jackson Daily News, June 19, 1912: 6.

21 Search for words “Poll Perritt” or “Pol Perritt” or “Polly Perritt” in New York, Missouri, or Louisiana newspapers available on Newspaper.com. Searches performed August 23, 2020.

22 Dent M’Skimming, “Cincy Games Are Important,” St. Louis Star, September 12, 1914: 6.

23 Billy Murphy, “Perritt One Pitcher Who Has Never Received Credit for Brilliant Work In Box”; “Fanning and Panning,” St. Louis Star, September 4, 1914: 6; “Auto News and Gossip,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 17, 1915: Sports, 4.

24 “Perritt Says Row with Britton Led to Fed Jump.,” Buffalo Enquirer, March 6, 1915: 8.

25 Dent M’Skimming, “Perritt Is Loyal to Cards,” St. Louis Star, September 14, 1914: 6.

26 “Perritt Holds Conference with Owner Britton,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 18, 1914: Sports, 2.

27 W.J. O’Connor, “Feds Seeking to Wreck Cardinals and Herzog’s Reds,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 15, 1914: 23.

28 “Cards’ Side of Perritt Deal; Waits on Decision of Judge; Wingo Trade Is in Same Situation,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 3, 1915: 14; “Ray Caldwell Ready to Return to the Yankees; Wingo Admits ‘Back Flop,’” Buffalo Courier, January 7, 1915: 12.

29 Harry F. Pierce, “Perritt and Oakes Battle in a Cafe; Pitcher-Jump,” St. Louis Star, January 2, 1915: 7.

30 “No O.B. Players Jumped Contract in Joining Feds,” Buffalo Times, March 7, 1915: 71.

31 Harry F. Pierce, “Hub Perdue Obeys ‘Hug’s’ Orders and Indians Tie Game,” St. Louis Star, March 15, 1915: 11.

32 J.V. Linck, “Giant Expected to Play in Spring Series Sunday,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 26, 1915: 10.

33 “Alexander Too Much for Crippled Giants,” New York Tribune, May 2, 1915: 13.

34 Heywood Broun, “Poll Perritt Takes Lesson from Matty,” New York Tribune, May 14, 1915: 14.

35 “Sports of All Sorts,” Binghamton (New York) Press, May 29, 1915: 15.

36 “Cardinals Drop Two to Giants,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 18, 1915: Sporting Section, 1.

37 Jerome Beatty, “Cupid Signs Up Poll Perritt in Hymen’s League,” New York Tribune, October 19, 1915: 13.

38 “‘Polly’ Perritt Weds Tesreau’s Sister-in-Law,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 19, 1915: 10.

39 W.J O’Connor, “Austin’s Future — Give Jones Anxious Moments,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 28, 1916: 18.

40 “Mathewson Is Now Manager of Reds,” New York Times, July 21, 1916: 6.

41 “Poll Perritt Pitches Two Games and Wins,” New York Tribune, September 10, 1916: Sports, 1.

42 Frank O’Neill, “Robins’ Victory Over Giants Gains Ground on Threatening Phillies,” New York Tribune, October 3, 1916: 14.

43 “Stallings Says It Is Do or Die for Braves in Series with Phils,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 2, 1916: 14.

44 Frank O’Neill, “Dodgers Rout Giants in Crucial Battle,” New York Tribune, October 4, 1916: 16; “Superbas Capture National Pennant,” New York Times, October 4, 1916: 12.

45 “Too Much for McGraw,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 4, 1916: 14.

46 “Brooklyn Wins National League Flag; Giants Are Accused of Lying Down,” Binghamton Press, October 4, 1916: 13.

47 “M’Graw Accuses His Men of Quitting,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 4, 1916: 14.

48 “Commission Fails to Take Action on Giants ‘Lay Down,’” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 5, 1916: 12.

49 Grantland Rice, “Listless Work of Giants Justly Angers McGraw and Spoils the Finish of Great Pennant Race,” New York Tribune, October 4, 1916: 16.

50 W.J. O’Connor, “Giants Again Rough-Riding Over Umpires and Players,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 4, 1917: 20.

51 W.J. Macbeth, “Perritt on Edge for Big Series with White Sox,” New York Tribune, September 16, 1917: Sporting Section, 4.

52 “Karpe’s Comment on Sport Topics,” Buffalo Evening News, August 24, 1918: 14.

53 “Sports Chatter,” Buffalo Times, January 30, 1919: 16.

54 “Double-Header Briefs,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 19, 1918: 8.

55 “Double-Header Briefs”; “Chase Accused in Affidavits,” New York Times, October 4, 1920: 8.

56 “‘Red’ Causey Steers Giants to Victory,” New York Tribune, July 18, 1918.

57 J. Erry, “Only Natural Mathewson and Chase Should Come to Parting of the Ways,” Dayton Daily News, August 8, 1918: 16.

58 “Heydler Reserves Decision in Case,” New York Times, January 31, 1919: 12.

59 W.J. Macbeth, “Star Among First Baseman Not Guilty,” New York Tribune, February 6, 1919: 17.

60 Thomas S. Rice, “Daubert for Reds Would Suit Nicely,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 31, 1919: 1, 2.

61 Frederick G. Lieb, “Date for Hearing in Chase Case Set,” New York Sun, January 22, 1919: 13.

62 “Poll Perritt a Holdout,” Buffalo Courier, March 3, 1919: 8.

63 “‘Poll’ Perritt Takes Place on ‘Oil’ Mound,” Shreveport Times, September 22, 1918: 12.

64 “‘Pol’ Perritt Turns Down 1919 Contract with New York Team,” Shreveport Journal, February 10, 1919: 5.

65 Mike O’Neil Doing Stunts in Oil Business Out West,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, March 29, 1919: 8.

66 “Oilers Stave Off Shut-Out,” Shreveport Journal, April 7, 1919: Sports, 1.

67 “Perritt Signs Contract,” Shreveport Journal, May 22, 1919: 7.

68 “Schupp and Perritt Are Not Reliable,” Ithaca (New York) Journal, July 15, 1919: 8.

69 Daniel, “High Lights and Shadows in All Sphere of Sport,” New York Sun, August 18, 1919: 15.

70 “American Giants Victors,” New York Sun, August 25, 1919: 14.

71 “Yanks to Fight for Series Coin,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 29, 1919: 26.

72 “Giants Exercise Options on Fifteen Players,” New York Tribune, August 18, 1920: 10.

73 “Thirteen Giants Going on Exhibition Trip to Cuba,” Buffalo Courier, October 12, 1920: 9.

74 “Pol Perritt to Train with Giants in Spring,” Shreveport Times, November 25, 1920: 8.

75 “Giants Release Perritt,” New York Tribune, June 4, 1921: 10.

76 “Athletes Idle Saturday; Two Games Monday,” Detroit Free Press, July 20, 1921: Sports, 1.

77 “Miller Owners Sign ‘Pol’ Perritt, Former Star Pitcher of New York Giants,” Minnesota Daily Star (Minneapolis), July 13, 1921: 6.

78 “Yips Make Clean Sweep of Series,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette, September 7, 1921: 7.

79 Earl Arnold, “Five Pitchers Fail to Stop Saintly Foes,” Minneapolis Tribune, September 19, 1921: 10.

80 “Moffitt Will Put Down Well,” Shreveport Times, February 18, 1927: 18.

81 “Former Giant Pitcher Fined $50 for Assault,” Shreveport Journal, May 2, 1928: 6.

82 W.J. Macbeth, “Perritt on Edge for Big Series With White Sox,” New York Tribune, September 16, 1917: Sporting Section, 4.

83 “Two Oil Men Face Charges as Sequel to Fight at Hotel,” Shreveport Journal, August 28, 1934: 1, 8.

84 “Mrs. ‘Poll’ Perritt Rites Held in New York,” Shreveport Journal, July 10, 1944: 13.

85 “Obituary: Florence Perritt Hawkins,” Shreveport Times, 2008. https://legacy.com/obituaries/shreveporttimes/obituary.aspx?n=florence-perritt-hawkins&pid=116197304, retrieved June 17, 2020.

86 “Obituary: Helen Perritt Miller,” Shreveport Times, July 12, 1987: 22.

87 “Obituaries: Henry Walker Perritt,” Shreveport Times, February 26, 1990: 6.

88 “Services in Arcadia for Father of Oilman,” Shreveport Journal, April 20, 1955: C5.

89 “W.D. (Pol) Perritt Dies Wednesday,” Shreveport Journal, October 16, 1947: 1.

Full Name

William Dayton Perritt

Born

August 30, 1891 at Arcadia, LA (USA)

Died

October 15, 1947 at Shreveport, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.