Tigers and Crescents and Clowns, Oh My! Negro League Baseball at Crosley Field

This article was written by Alan Cohen

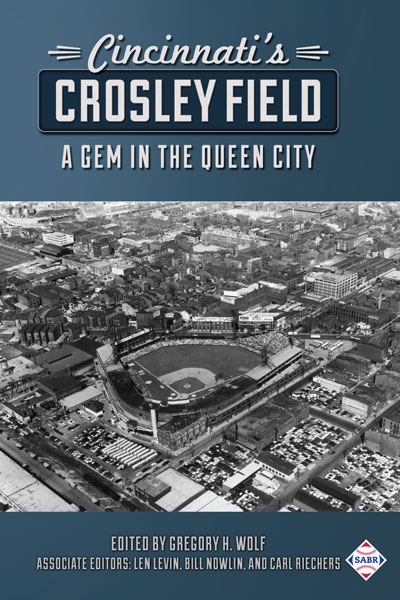

This article was published in Crosley Field essays

“My favorite experience of ’em all – and I’ve seen baseball on all levels – was the Clowns at Crosley. I could swear I could smell the grass growin’ during a light rain. It was intimate. The style of play was nice and loose, the way I learned to play it.” – Moses Hudson, 1993.1

Black baseball was a fun, athletic, comedic, and proud enterprise that made its way across the national landscape during the first half of the twentieth century. Crosley Field provided a home to several Negro League teams beginning in 1934.

Black baseball was a fun, athletic, comedic, and proud enterprise that made its way across the national landscape during the first half of the twentieth century. Crosley Field provided a home to several Negro League teams beginning in 1934.

The Cincinnati Tigers were the first Negro League team to play at Crosley Field. They first emerged in 1934 as an independent team. They opened their home season at Redland Field and first played at Crosley Field on May 20, 1934, against the Kansas City Monarchs. The Monarchs won 10-3 behind the seven-hit pitching of Chet Brewer. Jess Houston and Virgil Spears each had two hits for Cincinnati, but they were unable to mount a rally. The decisive blow was a three-run homer by Monarchs second baseman Dink Mothell.2 The Tigers played independently, often at Crosley Field, through 1936. In 1937, they were one of the original eight teams in the Negro American League and once again played at Crosley Field. It was their only season in the NAL. They finished in third place during the first half of the season with a 15-11 record, and the following season were reborn as the Memphis Red Sox.3

In 1941, the touring Miami Ethiopian Clowns, owned by Syd Pollock, took the field on June 8. Instrumental in the planning for the event were Abe Saperstein, owner of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball team, and Warren Giles of the Cincinnati Reds. The Clowns played a brand of baseball that was as much comedic as athletic. Crosley Field, at the time, was one of seven big-league parks to host Negro League baseball.4 Opposing the Clowns were the Satchel Paige All-Stars. A crowd of 12,000 was on hand as the teams split two games. The Clowns won the first game, 1-0, in 10 innings, and Paige’s team came back to win the second game, 5-4. Paige started and pitched three scoreless innings in the second game, the only hit being made by Showboat Thomas, a first-inning triple. In the first game, Eddie Davis, also known as Peanuts Nyassas, had wowed the crowd not only with his pitching but also with his comedic touch, which included his famous “Shipwreck Walk.” Natchett pitched well for the Paige All-Stars in the opener, but got little in the way of offensive support. The Clowns also enthralled the crowd with their “2-Ball Lightning Infield Workout” routine that lasted two minutes.5

Frank “Fay” Young of the Chicago Defender had this to say about the Clowns: “The fans get a kick out of their funny antics. Also do these fans get a whale of a kick out of the brand of baseball these boys put up on the diamond. They make some of the dadgonest catches, the outfield moves at lightning speed to rob opponents of extra-base hits, and the infield is hustling all the time.”6

Off this showing, the Clowns were booked to return to Crosley Field on June 29 against the Cuban Giants. Peanuts Nyassas once again pitched the Clowns to victory, allowing only three hits in the first game. Paige, pitching for the Giants in this encounter, did not fare too well. The Clowns won both games of the doubleheader and knocked Paige around for four runs and five hits in the third inning of the opener.7

In 1993 John Erardi in one of a series of articles for the Cincinnati Enquirer, spoke with players and fans and came away telling his readers, “At Negro League games, you didn’t keep the foul balls. Tickets cost less, so you were expected to throw the foul balls back. Generally, there was more of a picnic atmosphere at Tigers and Clowns games. It was more of a social event – a happy get-together on Saturday and Sunday afternoons – because the games came about so rarely. People dressed up.”8

However, there were those, including Cumberland Posey, who took issue with the Clowns’ comedic play and were looking for more serious Negro League baseball to be played at Crosley Field. As Neil Lanctot noted in Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution, “the (often white) media recognition of Davis once again demonstrated that mainstream whites accepted and remained relatively unthreatened by blacks appearing as comedians.”9

On July 20, 1941, three Negro League teams came to play some serious baseball. In the first game, the Chicago American Giants faced the St. Louis Stars. The winner was matched up against the Memphis Red Sox. Playing in front of 8,000 fans, with Negro American League president, J.B. Martin, throwing out the first ball, St. Louis defeated Chicago, 11-7. It began as a pitchers’ duel between Willie Cornelius of Chicago and Frank McAllister of St. Louis, and Chicago led 4-2 after seven innings. Then St. Louis plated nine runs in the eighth inning. The game’s hitting star was Dan Wilson of St. Louis, who had four hits. McAllister struck out eight Chicago batters. In the second game, Memphis defeated St. Louis, 6-1, as Verdell “Lefty” Mathis pitched a four-hitter, defeating Eugene Smith.10

On August 20, 1941, Memphis, which featured six players who had played for the Cincinnati Tigers Negro League team in the 1930s, took on the Clowns in a doubleheader.

The following season, 1942, the Clowns relocated to Cincinnati and played in the upstart Negro Major Baseball League of America, drawing a record 12,500 for a game during May. That same season, the Cincinnati Buckeyes joined the Negro American League. Two Negro League teams in Cincinnati were not sustainable, and the Buckeyes moved to Cleveland during the season. The NMBLA was short-lived, and the following season, the Clowns moved on to the Negro American League and toned down their act. Over the next several years, the Clowns, when not barnstorming, split their “home” games between Indianapolis and Cincinnati.

“I saw Jesse Owens race a horse, outfielders throw the ball into a peach basket, and fans chase down greased pigs and chickens and then take them home to eat. Even White people went to the Clowns’ Games – Edgar Bradley, 1993.11

In 1946 Cincinnati had a team it could totally call its own. An independent operation, the Cincinnati Crescents came to town. They were headed by Winfield S. “Gus” Welch and Ted “Double-Duty” Radcliffe. Star power was provided by first baseman Luke Easter. During the season, the Negro American League Clowns called Crosley Field home for several games, as well.

The Crescents first games at Crosley Field were played on May 12 against the Havana La Palomas. It was not a favorable debut for the Crescents as they lost by scores of 6-5 and 3-2. The doubleheader was played in front of 6,500 fans. In the opener, the Crescents took a 4-2 lead but the Havana squad scored four runs to take the lead and go on to win. Luke Easter’s two singles and a double powered the Crescents offense, but they were not able to regain the lead. In the nightcap, the hero for the Cuban team was Len “Sloppy” Lindsay, who had two doubles and a single.12

The House of David All-Stars visited Crosley Field on May 30 for a doubleheader with the Crescents. The Crescents swept the doubleheader, winning by 11-4 and 5-4.

On June 27, the Crescents swept the Puerto Rican All-Stars, 4-3 and 6-5, at Crosley Field.

There were two doubleheaders with the Clowns to determine Negro League supremacy in the Queen City.

On July 7, 1946, the teams split two games, with the Clowns winning the opener, 9-1, and the Crescents taking the nightcap, 6-3, in seven innings. The star of first the game was Henry “Speed” Merchant of the Clowns. The center fielder had four hits, including a triple, and a sacrifice in five trips to the plate. Pitching for the Clowns was Atires “Perfecto” Garcia, who bested Johnny Markham. The game’s final outs resulted from a double play engineered by Reece “Goose” Tatum and Richard “King Tut” Kelly. Tatum, the team’s first baseman, was moved to second base and King Tut came in to play first base at the beginning of the ninth inning. Tatum was perhaps better known for his antics on the basketball court with the Harlem Globetrotters. The winning pitcher of the second game for the Crescents was Willie D. Smith, who allowed six hits in going the distance. In the second game, Merchant singled in his only plate appearance, as he injured his ankle and was forced to leave the game.13 Eddie “Peanuts Nyassas” Davis started the second game on the mound for the Clowns but was unable to contain the Crescents.14

On July 23, the Crescents hosted the Memphis Red Sox in a night game at Crosley Field. The hitting star was Easter, who struck his 41st home run of the season and added a triple in an 11-2 thrashing of Memphis by Cincinnati. Johnny Markham, the Crescents pitcher, limited Memphis to six hits.15

The Clowns and Crescents met for a second time at Crosley Field on August 4. As if a doubleheader were not enough of an enticement, a beauty contest was held as part of the festivities. The Crescents swept the twin bill, 6-2 and 3-2. The opener went 11 innings, with the Crescents scoring four times in the 11th for the win. In the nightcap, the Crescents came from behind on a homer by Howard “Duke” Cleveland and a run-scoring single by pitcher Ed Cathy. The sweep gave the Crescents the season’s series, three games to one.16

Although an independent team, the Crescents were a very good squad and their Sundays were spent in games against teams from the Negro National and Negro American Leagues. On August 18 at Crosley Field, they took on the Chicago American Giants. After a pregame fungo-hitting contest between Luke Easter and Chicago’s Ed “Pepper” Young, the Giants won the opener, 5-1, before succumbing to the Crescents, 3-0, in the finale.

And it wasn’t only the Crescents and Clowns in 1946. On September 6, the Kansas City Monarchs took on the Homestead Grays at Crosley Field. The Clowns faced the Monarchs two days later at Crosley.

W.S. Welch again fielded a team in 1947, but they played as the Detroit Senators and did not see action at Crosley Field. The Clowns played several games at Crosley Field, the first being against the Birmingham Black Barons on Memorial Day.17

The Crescents re-emerged at Crosley Field in 1948 under manager Howard Easterling and played a series of doubleheaders, the first of which was on June 27 against the Puerto Rico All-Stars.

On July 11, 1948, in a doubleheader at Crosley Field, four Negro League teams were represented. The Crescents defeated the Chivos, a local semipro team, and the Homestead Grays defeated the San Francisco Sea Lions.

The lure of Negro League ball was vanishing in 1948 as major leagues were in the second year of integration. Meaningful Black baseball contests at Crosley Field were on the decline. On May 23, the Birmingham Black Barons came to play against the Chicago American Giants. Chicago swept the two games, 7-5 and 5-3, breaking an eight-game Birmingham winning streak in the process. The only other meaningful game of Black baseball in Cincinnati in 1948 was played at Crosley Field on August 24, when the Chicago American Giants faced off against the Cleveland Buckeyes in a Negro American League game.

In 1949 the Clowns, based in Indianapolis, were part of a revamped 10-team Negro American League (the Negro National League’s last year was 1948). They returned to Crosley Field with many of the characters who had delighted Cincinnati fans over the years, including Peanuts Nyassas and Goose Tatum, to face the Houston Eagles on July 18, 1949. Houston won, 5-2. It was the last appearance of the Clowns at Crosley Field. By the time the 1950 season began, the Negro Leagues were but a memory and the few remaining Black teams including the Clowns would caravan around the country making a living where they could, mostly in smaller towns. Crosley Field on June 25, 1950, once again welcomed Satchel Paige. He was pitching with the Grand Rapids Black Sox when they took on the Homestead Grays. The Grays won, 7-1 and 5-1, and got back on the bus.

The days of Black baseball in big-league parks were all but over, but the Clowns returned to Crosley Field in 1953, playing the Kansas City Monarchs on July 3 and the Memphis Red Sox on August 21 in Negro American League Games. In the Clowns lineup was a barrier-breaker. Marcenia Lynn “Toni” Stone was a female second baseman who was getting rave notices. Syndicated columnist Dorothy Kilgallen offered that “she belts home runs as easily as most girls catch stitches in their knitting, and the sports boys are goggle-eyed.”18 Stone hit .243 in 50 games for the Clowns in 1953, including a single off Satchel Paige.19

And she joined the men on the bus.

ALAN COHEN has been a SABR member since 2011, serves as vice president-treasurer of the Connecticut Smoky Joe Wood Chapter, and is the datacaster (stringer) for the Hartford Yard Goats, the Double-A affiliate of the Colorado Rockies. He has written more than 40 biographies for SABR’s BioProject and more than 30 games for SABR’s Games project, and has contributed stories to The National Pastime and the Baseball Research Journal. He has expanded his BRJ article on the Hearst Sandlot Classic (1946-1965), an annual youth All-Star game which launched the careers of 88 major-league players. He has four children and six grandchildren and resides in West Hartford, Connecticut, with his wife, Frances, one cat (Morty), and two dogs (Sam and Sheba).

Sources

In addition to the sources included in the notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com and recommends the following sources for information on the subjects included in this article.

Erardi, John. “The Negro Leagues and Cincinnati: Swing Was Good but Timing Was Bad,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 5, 1993: C17, C19-C20.

Mohl, Raymond A. “Clowning Around: The Miami Ethiopian Clowns and Cultural Conflict in Black Baseball,” in Tequesta, 2002: 40-61.

Notes

1 John Erardi, “No Souvenirs – Just Memories: At Negro League Games, You Didn’t Keep Foul Balls,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 5, 1993: C21.

2 “Tigers Are Beaten,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 21, 1934:14.

3 Leslie A. Heaphy, The Negro Leagues: 1869-1960 (Jefferson City, North Carolina: McFarland Publishers, 2003), 114.

4 “Clowns in Cincy on June 8,” Chicago Defender, May 24, 1941: 24.

5 “Clowns, Satchel Paige Split Double Bill,” Norfolk News Journal and Guide, June 21, 1941: 13.

6 Fay Young, “The Stuff is Here – Past, Present, Future,” Chicago Defender, June 14, 1941: 42.

7 “3-Team League Twin-Bill in Cincy July 20,” Chicago Defender, July 5, 1941: 23.

8 John Erardi, “No Souvenirs.”

9 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 228.

10 “St. Louis Stars Defeat Chicago Then Lose to Memphis Red Sox, 6-1,” Chicago Defender, July 26, 1941: 22.

11 John Erardi, “The Negro Leagues in Cincinnati – Pictoral,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 5, 1993: C23.

12 “La Palomas Take Two from Crescents,” Chicago Defender, May 18, 1946: 11.

13 “Clowns Split with Crescents,” Chicago Defender, July 13, 1946:10.

14 “Cincinnati (sic) Clowns and Cincinnati Crescents Divide in Double Bill,” Atlanta Daily World, July 12, 1946: 5.

15 “Easter Whole Show as Crescents Win,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 24, 1946: 13.

16 “Crescents Victors in Clowns’ Series,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 5, 1946: 14.

17 “Baseball Chatter,” Los Angeles Sentinel, May 29, 1947: 23.

18 Dorothy Kilgallen, “Jottings in Pencil,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 13, 1953:11.

19 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro League Baseball League (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 746.