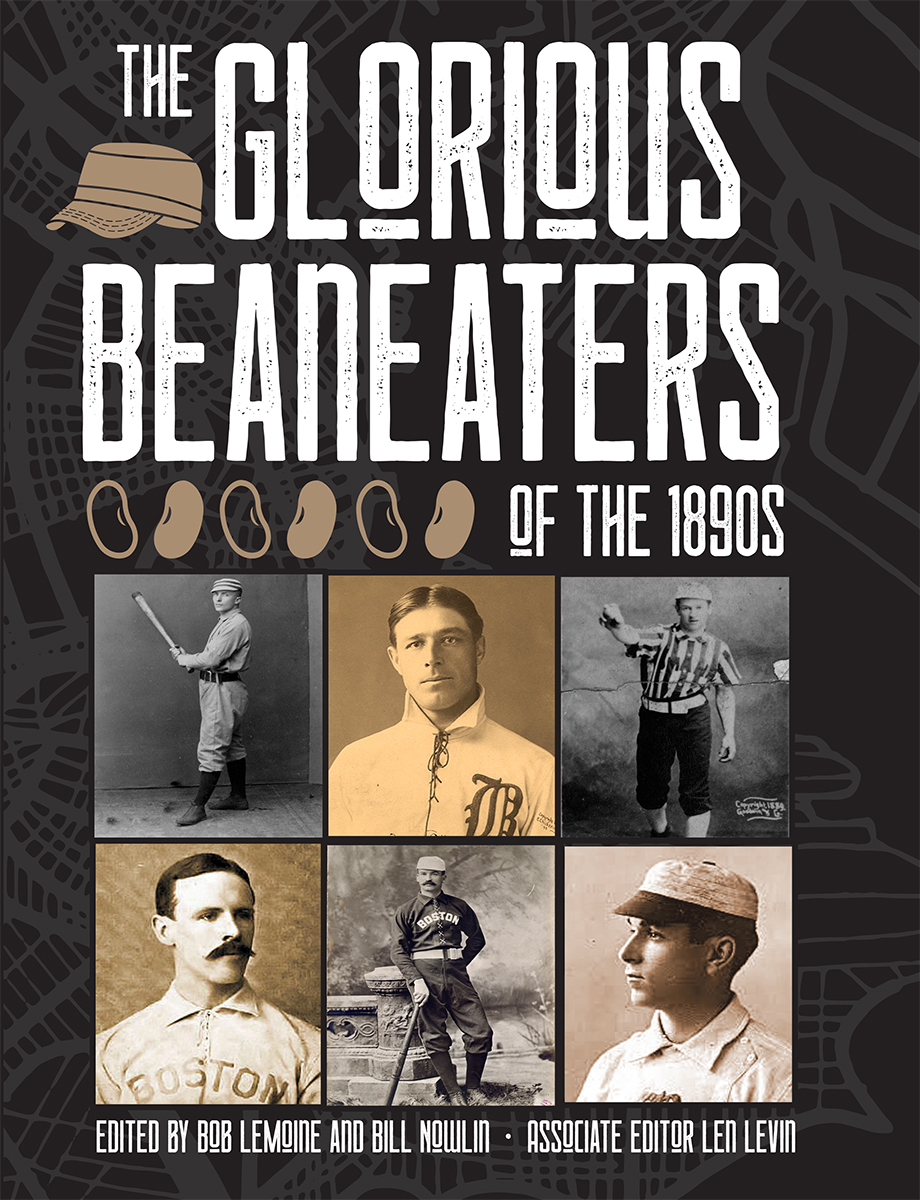

1897 Beaneaters: Boston’s Crusade

This article was written by Bill Felber

This article was published in 1890s Boston Beaneaters essays

The 1897 Beaneaters opened spring training in Macon, Georgia, with optimism that may have been out of proportion to their 74-47 fourth-place finish, 17 games behind the champion Baltimore Orioles, a year earlier. The core of the team was familiar: Tommy Tucker, Bobby Lowe, Herman Long, and Jimmy Collins across the infield, Hugh Duffy and Billy Hamilton forming two-thirds of the outfield, and Kid Nichols leading the pitching staff. Fred Tenney, who had inherited the right-field job when Jimmy Bannon was released late in the 1896 season, prepared to assume that duty full time. Reliable Jack Stivetts and youngsters Fred Klobedanz and Ted Lewis appeared ready to support Nichols as needed on the mound.

However high the Beaneaters’ hopes were, the schedule maker could not have created a more imposing start to the season. It began with a thoroughly disappointing April 19 Patriots Day home opener against Philadelphia marred by the club’s inability to touch Phillies ace Al Orth and by Nap Lajoie’s three-run eighth-inning home run that gave the visitors a 6-0 advantage. A desperate two-out ninth-inning rally produced two runs and loaded the bases for Tucker, who drove an Orth pitch high off the wall in the recesses of right field for a three-run double. The shot barely missed leaving the playing area for a game-tying grand slam; in fact, witnesses agreed it would have gone out had not Beaneaters management raised the fence by a few feet during the offseason. As it was, Tucker stopped at second and he died there when Orth retired Charles Ganzel on a game-ending infield grounder.

The opening road trip, a three-city, eight-game swing, began three days later in Baltimore, where that city celebrated its three-time defending champions on April 22 with a parade from the Eutaw House downtown to the ballpark, 2½ miles away. The city virtually closed for the occasion, an estimated 1,000 bankers and merchants opting to hail their heroes rather than work. While players were the main attractions, one of the attention-getting floats featured the 1894, 1895, and 1896 championship trophies as well as the 1896 Temple Cup, which the Orioles had won the previous October by beating the Cleveland Spiders.

Once at the park, the entire parade order was reassembled inside the gates for a march to the center-field flagpole, where the three pennants were unfurled and raised.

The Beaneaters, whose role through all of this was accoutremental, seized their chance to actually do something once play began. Halfway through the contest, they led 5-4. But Stivetts, the starting pitcher, complained to manager Frank Seleeabout a sore arm and the Orioles tore into Klobedanz, his replacement for the sixth. It was the kind of ethically questionable rally the Orioles had become famous for, beginning when Hughie Jennings leaned into a pitch that hit him. Umpire Tom Lynch ignored Beaneater protests that Jennings should have been denied his base for failure to make an effort to get out of the way, and moments later Jack Doyle drove a pitch over Hamilton’s head in center, producing three game-changing runs. The Orioles won, 10-5.

The series’ second game was more of the same. Nichols protected a 5-4 lead into the eighth inning when Willie Keelerslapped a single past Lowe. Jennings followed with a hit that sent Keeler to third, and when Jennings’ successful attempt to steal second drew Doc Yeager’s throw, Keeler trotted home with the tying run. A Collins error and two hits later, the Orioles led by their eventual winning score, 7-5.

In the third game, Joe Corbett – brother of former heavyweight champion James J. Corbett and a lightly used member of the Orioles 1896 staff – announced his presence for 1897 by stifling the Beaneaters’ bats, 7-1, to complete the series sweep. The Orioles’ most pleasant mound surprise, Corbett – who had made just six career starts to that point – would win 24 times for the Orioles in 37 appearances.

The train ride to Philadelphia provided Selee a chance to ponder a quick makeover. Tucker, showing the effects of age both at bat and at first base, was benched, to be succeeded by Tenney. (Tucker would be sold to Washington in June.) The latter’s place in right field was given over to rookie Chick Stahl. But the revised lineup managed just one win and two ties in the trip’s remaining five games in Philadelphia and Washington, outcomes made more depressing by Collins and Long errors undermining Lewis’s work in a 5-3 loss to the Senators. “Put that mob in cotton and ship them to Oshkosh,” a fan wired Selee of his 1-6 team.1

Equilibrium

The Beaneaters could not have sensed it at that moment, but less than two weeks into the season they had already weathered their stormiest stretch of play. Yet the coming together was less an epiphany than a gradual process of talented players gradually rising to their level. They were .500 (9-9) after defeating Cleveland on May 15, and two days later launched a six-game winning streak, outlasting the Chicago White Stockings 7-6 in 10 innings. Their first visit to St. Louis for a series against the woeful Browns produced three wins, scoring 11 runs in each of the three games while the Browns scored a total of nine. On the Western swing that concluded on May 29, they had gone 12-5 and lifted themselves from eighth place to fourth, five games behind the Orioles.

Even better, the schedule called for the same Western teams the Beaneaters had just collectively dispatched to visit Boston during most of the month of June. “I fully believe the home team will pass all the teams higher up in the standings before long and be in position to fight Baltimore for the lead when that team arrives here late in the month (June 24-26),” predicted Tim Murnane, the best-known sports reporter of the era.2 He was right: The Beaneaters launched a 17-game winning streak. It began with a crushing 25-5 dispatch of the hapless Browns May 31 and a doubleheader sweep of the Browns the next day, this time by scores of 14-6 and 12-3. In six games against St. Louis over the previous 10 days, the Beaneaters had scored 84 runs, the Browns 23. The Spiders and Louisville Colonels were both dispatched twice, the Pirates, Reds and Cubs three times, and the Dodgers once. Between May 20 and June 25, the Beaneaters played 29 games, winning all but three by an average margin of five runs and scoring in double digits 16 times. Aside from Marty Bergen, every Beaneaters regular was hitting above .300, and Duffy was pushing .400. When the Giants swept a doubleheader from Baltimore on June 21, the streaking Beaneaters completed their ascent in the standings, jumping a half-game ahead of the Orioles. Coming off a 1-6 month of April, they had won 17 of 23 in May and 22 of 24 in June.

The momentum was undeniable, even to Selee. “I have managed three champion league teams for Boston,” he said, “but the team I have this year is stronger than any I ever managed before.”3

Turbulence

The Beaneaters’ 5-1 victory over Cincinnati on June 12, in the midst of the streak, provided a glimpse into one of those moments that makes 1890s baseball deliciously larcenous. In the sixth inning, with Nichols working on a 3-0 shutout, Tommy Corcoran stood at third and Jake Beckley at second when Claude Ritchey rolled a one-out grounder to Bobby Lowe. Corcoran scored and Beckley followed him around seconds later, only to be called out by umpire Tim Hurst for failing to touch third base even though Hurst’s attention had been focused on the play at first. Witnesses later said Beckley had actually cut the bag by 20 feet, trying to take advantage of the fact that Hurst could not see him. But Hurst knew it would have been impossible for Beckley to score as quickly as he did by legitimate means. “As I saw him coming I said to myself, ‘O, what a bluff, but I’ve got you this trip,’” Hurst said after the game.4

Seventeen-game winning streaks ought to go a long way to promoting team unity, but that was not always the case among the Beaneaters, and particularly as it involved Bergen. A troubled individual who would 2½ years later murder his wife and children, then kill himself, he was probably schizophrenic, although such a diagnosis did not exist in those days. Certainly he was prone to periodic fits of imagined wrongs at the hands of his teammates. During one of the June games against the White Stockings, he lashed out at teammates he imagined were talking disparagingly of him behind his back, leaving the team for several days and returning home. Yet as much as Bergen agitated Selee’s life needlessly, the Beaneaters manager needed his arm and field generalship behind the plate. When the Dodgers finally snapped Boston’s winning streak on June 22, they stole three bases in key situations off backup Charlie Ganzel. So it was with a mixture of trepidation and relief that his teammates welcomed Bergen back to the clubhouse before the start of the Orioles series, with the Beaneaters clinging to their half-game lead.

A local cigar company offered Boston players a free box of cigars in exchange for a hit in that opener, which pitted Nichols against Jerry Nops. The cigar tab went up drastically when fans stormed the South End Grounds, hundreds of them penned behind outfield ropes that shrunk the playing surface to something approaching youth league dimensions. “The game was a pure farce … (the field) not much larger than a tennis court,” the Baltimore Sun’s correspondent complained.5 Taking full advantage of the confines, Beaneaters batters pounded out 19 or 20 hits (accounts differ), five by Duffy alone, while Nichols held the Orioles relatively in check for a 12-5 win. “Next to winning a game of ball, the thing that pleases me the most is a quiet half hour with one of these cigars,” Duffy told a reporter afterward.6 The most disquieting moment for Beaneaters partisans was a foul tip that fractured one of Bergen’s fingers, sidelining him again, this time for physical reasons.

Baltimore led the next day’s game, 9-8, with two out in the ninth when Bill Hoffer, the starting pitcher, began to wobble. Collins rolled a single through an opening on the right side, then Hoffer walked Ganzel and Stahl, filling the bases. Tenney took two strikes and smacked a line drive into the gap between Keeler and Jake Stenzel in right-center, a game-winning hit that touched off the type of walk-off celebration that is common today, but which was rare in the 1890s. The crowd burst on the field, swept Tenney off his feet, and carried him to the grandstand to receive its tribute. He emerged literally bruised for the experience, and hobbled through the series’ final game, a 1-0 Oriole victory with Corbett bettering Nichols before a crowd estimated at 17,000. For the record, the park’s listed capacity was 6,800.

Birth of the Rooters

In the afterglow of the enthusiasm sweeping through the city emerged an entity unique for its time, an organized fan club. The Royal Rooters were a semi-organized collection of fans that coalesced in June and July to celebrate and revel in the achievements of their Beaneaters. It was, by the standards of baseball fandom, a noteworthy assemblage, featuring – among others – Congressman John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, the future grandfather of President John F. Kennedy. As a group, the Rooters divided their time between two sites. The first was South End Grounds itself, where they established a more or less permanent presence in the seats adjacent to the Boston bench. The second was 3rd Base, a tavern owned by Rooter Michael “Nuf Ced” McGreevy,7 whose nickname derived from his habit of ending all baseball-related disputes with the declaration “Nuf Ced.” McGreevy outfitted his business with décor designed to celebrate the group’s heroes, including dozens of photos as well as chandeliers made of old Beaneater bats.

Having seized first place just prior to the Baltimore series, the Beaneaters spent the next several weeks methodically fortifying their advantage. After the series-ending 1-0 loss to Corbett, they reeled off eight more wins in succession, leading by 5½ games. It was all too efficient to be maintained; in Chicago the Beaneaters lost three straight one-run decisions, touching off a 2-6 stretch that reduced their advantage over the Oriole to 2½ games. Among those losses was a contentious one in Pittsburgh whose resolution illustrated several of the rough-and-tumble idiosyncrasies of 1890s baseball.

The Pirates, who had chosen to bat first, led by the eventual final score of 5-4 when Lowe drew a one-out base on balls and Bergen followed with a single in the bottom of the ninth. The afternoon had been rife with vulgar bench jockeying involving exchanges between Duffy, Pittsburgh pitcher Frank Killen, and fans. There were two out with Lowe at third and Bob Allen at second when Hamilton slipped a slow bounder toward second baseman Dick Padden and sped off toward first. Observers agreed that Hamilton arrived at the base simultaneously with Padden’s throw to first baseman Denny Lyons; in fact, the throw pulled Lyons into Hamilton’s path and the collision sent both players sprawling. Lowe, of course, crossed home plate easily and Allen, with no reason to stop running, also touched home before Lyons could recover his equilibrium. But did either of the runs count, or had Hamilton been retired at first, ending the game? Initially, umpire Bob Emslie made no clear signal, bringing both teams onto the field to celebrate their victory. Finally, Emslie signaled that Hamilton had been out at first, neither run counted, and Pittsburgh had won.

The pennant fight

The Beaneaters lead was three games when the Orioles made their final trip into Boston for the start of a three-game series on August 5. Aside from the decisive final-week series in Baltimore, these contests may have been the most contentious and most closely watched in baseball history to that point. It caught the attention of much of the sporting nation, which viewed it in terms that touched a national sense of right and wrong. There was not much question which side the three-time defending champions represented. Known for their cutthroat, brawling, and often under-handed methods of play, the Orioles had made enemies almost everywhere they played. The Beaneaters were no saints, but compared with their foes they inherited that image by default and wore it proudly. An editorial in the Pittsburgh Dispatch summed up the mood. “The most important point … is the superiority of the Bostons over the Baltimores as gentlemen. The latter have degenerated into a set of rowdies who resort to the smallest and dirtiest tricks ever seen on the ball field. How different it is with the Boston team.”8

League President Nick Young decided the games were of such importance that he should assign two umpires, not just one, to work them. The league’s senior umpire, Thomas Lynch, was an obvious choice, and Lynch’s second pick was Tommy Connolly, a future Hall of Famer at the time working in a regional minor league. Young was stunned, however, when Connolly declined the offer to work such highly visible major-league games, citing prior commitments to his minor league. The real reason for Connolly’s hesitation was the fetid atmosphere surrounding the games. He did not want to be a part of the antics he thought likely to ensue.

Whatever one thinks of Connolly’s action, his instincts proved solid. During the first few innings of the opening game, Beaneaters players and fans continuously berated Lynch for what they saw as his failure to prevent Orioles starter Joe Corbett from cheating forward off the pitching rubber. When Lynch finally did issue a warning, Doyle, Jennings, and John McGraw took up Corbett’s cause. The game was Baltimore’s pretty much from the start, the Orioles pushing four first-inning runs across against Nichols and coasting from there.

Baltimore again seized an early lead in the series’ second game, but this time the Beaneaters rallied … and that rally set off a chain of events that rocked the baseball world. In the top of the eighth inning, Lowe drove a triple over Stenzel’s head to the wall in center and Bergen rifled a single to right, giving Boston a 6-5 lead. In the bottom of the inning, Doyle, whose nickname of Dirty Jack betrayed his reputation as the Orioles’ most tempestuous player, popped an easy foul to Bergen, then unleashed a string of epithets toward Lynch. When the Orioles took the field for the top of the ninth, Doyle repeated his verbal assault and Lynch ejected him. Now teammates joined Doyle in surrounding Lynch, each of them verbally assaulting the umpire, and Lynch returning insult for insult. It’s not clear who threw the first actual punch, but Doyle punched Lynch in the eye, blackening it, and Lynch sent Doyle sprawling with a full left to the player’s neck. Kelley and Corbett raced to separate the combatants, and their presence brought fans streaming from the stands onto the field. “The cry was to mob the Baltimore players and it doubtless would have been done” had not Boston players and police jumped in to calm the fans. It took 10 minutes before the scene could be cleared sufficiently for play to resume.9

Compared with what had preceded, the game’s conclusion was uneventful. All it featured was some bottles thrown Kelley’s way, blatant interference and a disputed game-saving play. McGraw had reached second on Long’s one-out error, slightly wrenching his knee when he bowled over Tenney, who was blocking his way around first base. The injured McGraw left, replaced by the slower Joe Quinn. With two out, Jennings singled cleanly to Duffy in left and he fired home in time, Lynch said, to retire Quinn. “That Quinn was clearly safe was frankly admitted by some of the Boston writers,” the Baltimore Sun’s correspondent declared the following morning. Hanlon virtually accused Lynch of throwing the game, calling the umpire “at heart a Boston man and I know it.” He added that he knew “pretty well when a man makes an honest mistake.”10

Boston partisans told a far different story: The abusive Orioles were reaping their just rewards. “Numbers will be found who will excuse anybody for acting as Lynch did under … such provocation,” argued the Boston Journal’s J.C. Morse.11

Lynch notified Young that he would remain in his hotel room to nurse his injuries rather than umpire the Saturday game, forcing the league president to scramble for a replacement. Given the short notice, the best Young could find was Bill Carpenter, a rookie he had hired only a few weeks earlier. Boston city officials took it upon themselves to provide backup, assigning two members of the city’s police department to duty on the field, and 40 more to the grandstands. The officers were needed. In the first, Keeler loudly protested Carpenter’s ruling that he had been picked off first, and Carpenter promptly summoned the officers to restrain the player. Lewis did the rest, limiting the Orioles to five hits in a 4-2 Boston victory.

Road trip

The Beaneaters bade farewell to the Orioles in front by three games, a margin the Orioles reduced to a half-game over the ensuing several weeks. More significantly, the National League race had functionally been reduced to two combatants, with the third-place Giants 5½ games further back. Then, like twin comets streaking across the late-summer sky, they jointly spent the next month distancing themselves from the terrestrial portion of the league while never losing touch with one another. Between August 28 and September 22, the Beaneaters won 17 of their 21 decisions, the Orioles won 18 of 24, and neither team managed to open up a lead over the other that was larger than 10 percentage points.

The closeness of the race, overlaid by the ethical patina attached at that time to any challenge to the supremacy of the hated Orioles, ensured a steady buildup of interest, nationally as well as regionally, as a final-week series approached in Baltimore for September 24-27. Nowhere was this buildup more noticeable than in and around McGreevy’s 3rd Base Saloon, where the Royal Rooters conceived the idea of something unprecedented in sports at the time: A large-scale fan invasion of the other team’s home turf. At a cost of $25 apiece, more than 125 Rooters purchased a package that included steamship and rail travel, overnight accommodations, plus grandstand tickets to all three of the games. In Baltimore, fans lined up in rainy weather across several city blocks to get the tickets, and scammers hired women to pose as pregnant in order to be moved to the front of the line.

Ensconced at the Eutaw House the evening before the first game, the Beaneaters did something unexpected: They socialized with the Orioles. Proprietors of Ford’s Theater presented players on both sides with complimentary tickets to that evening’s presentation of A Man From Mexico, and the players who had fought so bitterly as recently as early August freely intermingled while enjoying the performance.

For Selee, there was but one problem: Bergen was not in town. The unreliable catcher had disappeared while the team passed through New York City on September 23, and his whereabouts was temporarily unknown. The matter resolved itself the morning of September 24, when Bergen showed up and blamed Selee for his absence. Several weeks earlier, the manager had scheduled an exhibition game against a local team in Jersey City for September 23 as a means of picking up a few extra dollars … a common activity at the time. As the importance of the Baltimore series grew, Selee canceled the exhibition … but nobody told Bergen, who that afternoon had been surprised to find himself the only person at the field.

Rooters who were unable to make the trip gathered Friday morning at the Music Hall, or in front of Boston’s several newspaper offices, to watch re-creations of the play-by-play. At the Union Street Grounds, the old wooden ballpark groaned beneath the weight of the estimated 13,000 who paid for entry, many standing in roped areas in the outfield. Thousands more perched atop the fence, or on rooftops across the streets, to peer in. The Royal Rooters huddled en masse behind the Boston bench, waving banners and raising what Orioles partisans described as an “unearthly din.”

The series on the field

Both managers sent their aces, Nichols (29-12) and Corbett (24-6), to the mound. The home team struck first, McGraw opening the game with a walk, stealing second, and scoring on Jennings’ single. Joe Kelley’s double between Duffy and Hamilton plated Jennings with a second run.

Through three innings Corbett was perfect. In the fourth, however, Doyle’s error allowed Tenney to score his team’s first run. In the fifth Long singled and Bergen doubled, tying the game. Lowe’s two-out hit a few moments later gave Boston its first lead, 3-2.

The Orioles repeatedly fell back on their “inside baseball” tactics, only to see the Beaneaters’ skill or their own errors of execution undermine them. In the third Collins raced in to field Keeler’s bunt attempt and threw him out. In the fourth, Stenzel was thrown out by Collins trying to score. Doyle attempted to steal second, only to have Bergen throw him out. Again in the fifth, McGraw tried to bunt but popped up to Nichols. In the sixth Bergen threw out Keeler attempting to steal second. It marked the fifth time that an Oriole had been retired on the bases.

Corbett’s errors helped the visitors break the game open in the seventh. With Nichols on first, he threw Hamilton’s easy grounder past Doyle into short right, allowing the runners to take second and third. Then he wild-pitched Nichols across. Tenney’s bunt single made the score 5-2. The Beaneaters added a sixth run in the eighth on Long’s double with Duffy at second.

A contributor for his offense, Long would soon become a hero for his defense. In the bottom of the inning, two walks and an infield hit filled the bases for Stenzel, who rocketed a shot toward left. Long leaped and snared the ball, ending the inning. “It was one of the greatest catches ever seen on the ballground,” asserted the Boston Globe’s Tim Murnane.12The Rooters rewarded Long in the most meaningful way possible, by showering him with silver coins in such volume that his teammates had to help the player collect them.

It was Long’s richest moment, but hardly his last. The Orioles mounted a ninth-inning rally that produced two runs and found runners at first and second with just one out for Keeler. He punched a line drive past the pitcher, but Long intercepted it and tossed to Lowe at second, doubling off Wilbert Robinson, the Orioles captain and lead runner, for a game-ending double play.

That evening at the Eutaw House, Selee held an impromptu press conference for the Rooters, at which he essentially guaranteed them the pennant. Congressman Fitzgerald, in a celebratory mood, hired a band, which played well into the night, ensuring that the inn’s guests – mostly the Boston players and delegation – would get little if any sleep. This was a particular concern for Collins, who had taken a foul ball off his face, swelling an eye shut. To address that concern, the Beaneaters applied the standard remedy of the day to Collins’s face: leeches.

The bleary-eyed players and fans awoke the next morning in time to pose for a group photo outside the hotel, then departed for the ballpark, where Klobedanz prepared to battle Bill Hoffer. The crowd was, if anything, even larger, and this time the home faithful were rewarded. In the first inning Keeler beat out a disputed infield hit and Kelley’s double scored him. In the second Collins botched McGraw’s bunt with runners at second and third, permitting both runs to come across. The Orioles led, 3-0. Boston rallied in the seventh, scoring two runs with Hamilton at third and Lowe at first after two were out. Lowe chose that moment to turn Baltimore’s gambling style of ball against the Orioles, breaking for second in the hope of drawing a throw that would enable Hamilton to score. He drew Robinson’s throw, all right, but Hamilton failed to break, prompting Lowe to retreat. When Jennings fired back to Doyle, Hamilton finally took off for home, but Doyle’s throw beat him for the third out.

The home team put the game out of reach moments later. Keeler singled, Jennings doubled, and Kelley drove them both across. The 6-3 final moved Baltimore back within a half-game of the Beaneaters. The result seemed to put the home fans in a mood the Royal Rooters described as puzzlingly friendly. “Someone yelled, “Three cheers for the Boston Rooters” and that’s what they were given … several times over. “We expected to be obnoxious to the crowd here,” one Rooter lamented of the cheerful reception.13

Sunday baseball being illegal in Maryland, many of the Rooters enjoyed a side trip to the nation’s capital. Collins, Tenney, and a few other players dined that evening at Baltimore’s Diamond Café, whose proprietors were McGraw and Robinson.

It did not take long on Monday morning for Baltimore team and city officials to realize that the decisive game was an event beyond their control. Orioles owner Harry von der Horst tried to shore up his undermanned staff of ticket-takers by joining them at the turnstiles, only to see those same turnstiles literally uprooted by late morning. Outside the ballpark, speculators commanded six to ten times the face value for tickets. The trolley line required 10 minutes to traverse the few patron-thick blocks in front of the ballpark. The ropes that had been strung across the outfield to handle the first two days’ overflows were now extended, virtually eliminating foul territory beyond the bases and shrinking the playing surface substantially. By the time players arrived for warm-ups, estimates put the throng inside the gates at 20,000. Then, quickly, the crowd burst through the left-field gate itself, creating a gap through which hundreds more poured freely. By game time an estimated 30,000 were on hand, with thousands more clinging from telegraph poles or atop nearby rooftops. Although the precise number in attendance remains impossible to determine, it was almost certainly the largest crowd to watch a team sporting event in America to that date.

The outcome may have turned in the first inning when Chick Stahl’s line drive caromed off Corbett’s pitching hand, jamming several fingers and forcing him from the game. Boston took full advantage, scoring eight times by the end of the fourth inning. For Baltimore fans, the only saving grace was that the visitors and Nichols particularly were also off their game, Boston holding only an 8-5 lead entering the seventh.

That’s when the issue turned permanently. Hoffer, worn down by the combination of his Saturday effort plus his relief work to that moment, allowed consecutive hits to Duffy, Collins, Long, Bergen, Nichols, and Hamilton, two of them reaching the overflow crowd on the field for doubles. By the time Robinson cut down Long attempting to steal for the third out, the Beaneaters had touched the frazzled Orioles for nine runs on 11 hits. A half-hour later, the Royal Rooters celebrated a 19-10 Beaneaters victory.

The outcome left Boston 1½ games ahead of Baltimore and all but clinched the pennant, which was formalized three days later when they beat the Dodgers, 12-3, while Washington defeated the Orioles, 9-3. The Orioles and Beaneaters met a week later in the Temple Cup series, Baltimore gaining whatever consolation there was to be derived from their four-games-to-one victory. To the Beaneaters, the Royal Rooters, and also to the broader baseball world, that outcome was anticlimactic. What mattered was that Boston had ended the roughians’ three-year siege of the National League pennant and restored the franchise to its place at the forefront of the baseball world.

BILL FELBER is a retired newspaper editor. He is the author of numerous books on baseball, golf and the cavalry, among them A Game of Brawl: The Orioles, the Beaneaters and the Battle for the 1897 Pennant. He is a regular contributor to calltothepen.com.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied heavily on his book A Game of Brawl: The Orioles, the Beaneaters, and the Battle for the 1897 Pennant (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007).

Notes

1 T.H. Murnane, “Can’t Tell Why,” Boston Globe, April 30, 1897: 4.

2 T.H. Murnane, “Welcome the Team Today,” Boston Globe, May 31, 1897: 4.

3 Ibid.

4 T.H. Murnane, “Path to Pennant,” Boston Globe, June 14, 1897: 3.

5 “Orioles Were Too Easy,” Baltimore Sun, June 25, 1897: 6.

6 “Boston Wins,” Boston Globe, June 26, 1897: 7.

7 In records, the name is variously spelled as McGreevey; he spelled it both ways.

8 As printed in “Unjust Criticism,” Baltimore American, July 27, 1897. The American said the Dispatch article was “as unjust as it is uncalled for, and so far as the Baltimore club is concerned is not true.”

9 “Fight on the Diamond,” Baltimore Sun, August 7, 1897: 6.

10 Ibid.

11 “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, August 14, 1897: 9.

12 “They’re in the Lead,” Boston Globe, September 25, 1897: 1.

13 ‘Pennant Hopes,” Boston Herald, September 27, 1897: 1.