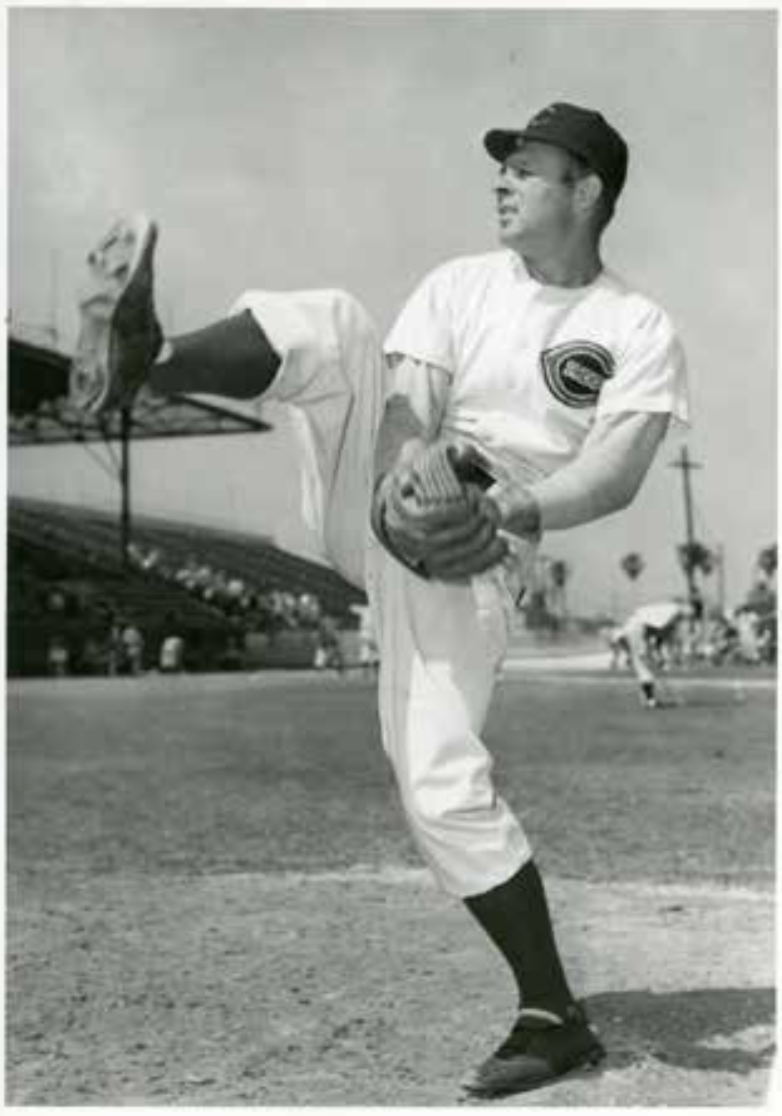

Johnny Vander Meer

Cincinnati Reds pitcher Johnny Vander Meer was close to achieving baseball immortality, but he didn’t know it. It was June 15, 1938, and he was on the mound in Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field with the bases loaded, two outs, and a 1-and-1 count on the irrepressible Dodgers shortstop Leo Durocher. One more out and his name would go into the record books as the first major-league player to pitch back-to-back no-hitters.

Cincinnati Reds pitcher Johnny Vander Meer was close to achieving baseball immortality, but he didn’t know it. It was June 15, 1938, and he was on the mound in Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field with the bases loaded, two outs, and a 1-and-1 count on the irrepressible Dodgers shortstop Leo Durocher. One more out and his name would go into the record books as the first major-league player to pitch back-to-back no-hitters.

Durocher, who was hitting just .256 but was tough in the clutch, dug in against the often-wild Vander Meer, who had walked eight that night but was comfortably ahead, 6-0. The left-hander reared back, kicked his leg high, and fired. Durocher hit a ball deep to right field that brought the crowd to its feet. It curved foul. The crowd let out a collective sigh of relief.

On the next pitch Vander Meer thought he caught the edge of the plate for strike three, but umpire Bill Stewart called it a ball, sending catcher Ernie Lombardi into a near rage. Hoots and catcalls rained from the Reds’ dugout. Vander Meer shrugged the call off and delivered again. This time Durocher lofted an easy fly ball to the sure-handed center fielder Harry Craft.

Teammates mobbed Vander Meer as he hurried off the field to avoid fans who ran on the field to congratulate him. Only in the dugout did he learn he had accomplished what no other pitcher in major-league baseball had: back-to-back no-hitters. And more than 75 years later, the feat has never been duplicated.1

John Samuel “The Dutch Master” or “Double No-Hit” Vander Meer was born on November 2, 1914, to deeply religious immigrant Dutch parents, Jacob and Kathy Vander Meer, in Prospect, New Jersey. He grew up in Midland Park, New Jersey, about 30 miles from New York City. There he learned to play baseball.2 His interest in baseball began at the age of 8 when he listened on the radio as the New York Giants swept the New York Yankees in the 1922 World Series. He began playing at 10 as a first baseman for his school at Stumps Oval, so-named because of its shape and the stumps left sticking up when trees were leveled.3

Vander Meer played ball every chance he could get. Then, at 14 he came down with peritonitis that nearly killed him. He was hospitalized for eight weeks and then spent five more at home.4 When he recovered, high school had already started so he dropped out. He went to work as an apprentice engraver at the factory where his father worked – and he continued to play baseball.

After his illness, Vander Meer’s weight shot up from 110 pounds to 175 by the time he was 17. (He eventually stood 6-feet-1 and weighed 190 pounds as a big leaguer.) And he had moved from first base to the pitching mound. He played for the Midland Rangers, who rarely lost when he was pitching, although he was cursed by wildness that would plague him throughout his baseball career. In 1932 Vander Meer pitched five no-hitters and finished the season 14-1.5

Vander Meer was hoping for a major-league career not only because of his love of the game but because he knew that without a high-school diploma, chances were slim for him to make a good living.6

Vandy caught the interest of a scout who arranged a tryout for him with the Giants, but he failed to attract much attention. He received a second chance, however, when National League officials began looking for a “typical American boy” to star in a film designed to promote baseball. His wholesome look filled the spot. The Dodgers sent him to Florida, where the documentary was filmed. Again he failed to attract interest – except from veteran pitcher Joe Shaute, who urged the Dodgers to give him a second chance.7 They relented and sent the 18-year-old Vander Meer off to pitch for the Dayton Ducks in the Class C Middle Atlantic League. His manager was the flamboyant Ducky Holmes and he was paid $125 a month.8

In his first year Vander Meer posted an 11-10 record with a 4.28 earned-run average. He struck out 132 and walked 74 in 183 innings. The Dodgers had first rights to Vander Meer, but when they inquired about him Holmes recommended that they not keep him or first baseman Frank McCormick, whom the Reds later picked up and who went on to win the MVP in 1940.9

Vander Meer wound up being sold to the Scranton Miners in the Class A New York-Penn League, where he improved, posting an 11-8 won-loss record with a 3.73 ERA in 164 innings. Wildness was becoming inherent in his pitching. In one game that he won 2-1, he walked 16 batters. It was at Scranton that Vander Meer fell, hurting his pitching shoulder, an injury that he said delayed his promotion to the major leagues.10

Although the Dodgers had earlier lost interest in Vander Meer, after his stint in Scranton they put in a claim that Dayton’s sale of Vander Meer to Scranton was illegal. Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, however, ruled that the Dodgers only showed renewed interest in Vander Meer when he started pitching better.11

Vander Meer stayed in Scranton but hurt his arm in the first game of the year and wound up with a 7-10 record and a 5.35 ERA, striking out 88 and walking 90 in 133 innings. It was in Scranton that Vander Meer met his future wife of more than 50 years.

Before the 1936 season Vander Meer was traded by Scranton to Durham in the Class B Piedmont League, a Cincinnati affiliate. There he turned his game around. He was 19-6 with a 2.65 ERA although his walks skyrocketed to 116 over 214 innings. He was named The Sporting News’ Minor League Player of the Year. The paper said the speed of his fastballs “makes it appear as though they’re hummingbird eggs.”12 The performance earned Vander Meer a late-season promotion to Nashville in the Southern Association, an A-1 league, where he went 0-1 in ten games with 25 walks and a 7.25 ERA in 22⅓ innings.

One apocryphal story had it that when Vandy was just missing the outside corner of the plate, coach Johnny Gooch moved the plate overnight when Vander Meer was scheduled to pitch the next day. His accuracy improved and then that night the plate was moved back.13

The Reds liked what they saw at Durham and invited Vander Meer to spring training in 1937. The Atlanta Constitution welcomed the pitcher with the headline, “Johnny May Cause Fans to Forget about Bob Feller in ’37.”14

Vander Meer was thrilled to reach the big leagues. But he didn’t last long. He didn’t think he was pitching enough, only once every ten days or so. And he didn’t get along with manager Charlie Dressen. General manager Warren Giles agreed to send Vander Meer to Syracuse to work on his game. He left Cincinnati with a record of 3-5 with an ERA of 3.85 with 52 strikeouts and 69 walks in 84 innings.15 In Syracuse, in the Double-A International League, he posted a 5-11 record but his ERA was a respectable 3.34 although he walked 80 in 105 innings. He called his wildness “the old bugaboo.”

During the winter Vander Meer wrote to Giles: “I know I’m a better ballplayer than the showing I made during the past season.” Giles thought so too and again Vander Meer was invited to spring training.16

When he arrived in Tampa for spring training he found a new manager, future Hall of Famer Bill McKechnie, who had replaced the fired Dressen. McKechnie was a godsend for Vander Meer. McKechnie was a player’s manager. Pitchers said fondly of him, “If you can’t pitch for McKechnie, you can’t pitch for anyone.”17

During that spring McKechnie and coach Hank Gowdy discovered a key to making Vander Meer a better pitcher: throwing overhand rather than half side-armed. He also got future Hall of Famer Lefty Grove to work with Vandy. McKechnie’s patience pleased Vander Meer. “I was able to concentrate on exactly what he told me,” he said. “I knew I didn’t have to rush or be afraid if I took my time.”18

As the 1938 season opened, Vander Meer figured that if he didn’t stick with the Reds this time, he would hang up his spikes.19 In his first outing he lost to the Pittsburgh Pirates 7-4, prompting McKechnie to put him in the bullpen, where he pitched in two games. Back as a starter, Vandy beat the Pirates this time 8-6 but had an 8-2 lead going into the ninth inning. An error and three hits knocked him out of the game, but he earned his first win. His lost his next game 2-0 to the Philadelphia Phillies but pitched a complete game. Next he blew a 5-1 lead against the Cardinals, losing 7-5. Then Vander Meer turned it around with a 4-0 blanking of the Giants in the Polo Grounds. That started him on a nine-game winning streak. The game before his first no-hitter, he beat the Giants again, 4-1, giving up only three hits, two in the first inning and a bloop single in the ninth.

On June 11 Vander Meer took the mound at home against the Boston Bees, the worst-hitting team in the National League with a .245 batting average. He was 5-2 and leading the league with 52 strikeouts. In pitching a no-hitter, Vander Meer gave up only four hard-hit balls; one was a liner by Vince DiMaggio off his glove that ricocheted to third baseman Lew Riggs, who threw DiMaggio out. Teammates carried the 23-year-old rookie off the field after the 3-0 shutout. “He’s a real pitcher,” Bees manager Casey Stengel said. “You watch him from now on. They’ll have trouble beating him.”20

On June 11 Vander Meer took the mound at home against the Boston Bees, the worst-hitting team in the National League with a .245 batting average. He was 5-2 and leading the league with 52 strikeouts. In pitching a no-hitter, Vander Meer gave up only four hard-hit balls; one was a liner by Vince DiMaggio off his glove that ricocheted to third baseman Lew Riggs, who threw DiMaggio out. Teammates carried the 23-year-old rookie off the field after the 3-0 shutout. “He’s a real pitcher,” Bees manager Casey Stengel said. “You watch him from now on. They’ll have trouble beating him.”20

In his next outing, on June 15, Vander Meer and the Reds visited Ebbets Field for the first night game in New York City. It was a banner night for the Dodgers with fireworks, a band, and Olympic star Jesse Owens racing against ballplayers. Five hundred fans from Vander Meer’s hometown, Midland Park, joined the festivities.

Vander Meer was going to put a damper on Brooklyn’s big celebration. Inning after inning he shut the Dodgers down to the point that even Brooklyn fans rooted for him to throw a second no-hitter. Once Durocher flied out, a new celebration was on 2 hours and 22 minutes after the game started. “If I’d known it had never been done before,” Vander Meer said, “it would have put more heat on me.”21

Vander Meer took his time showering with the hope that fans who might linger after the game to see him leave the park had given up and gone home. He told sportswriters he was going fishing the next day.

Up to that point only three pitchers before Vander Meer had thrown two no-hitters in their careers, Ted Breitenstein, Cy Young, and Christy Mathewson. Did he think he could throw three in a row? “I can’t say I’ll be out there for another no-hitter next time,” he told sportswriters. “I’ll just start out like I did last night and pitch my natural game. Then we’ll have to see what happens.”22

Before his next start Vander Meer was feted by his hometown, was offered lucrative endorsement packages, received a salary boost, was lauded in poetry, and was named the honorary mayor of Tampa, Florida, the home of the Reds’ spring-training site.

His next start was against the same Bees team he had beaten in his first no-hitter, but this time the game was in Boston. With Cy Young looking on – he had pitched 23 hitless innings spread out over several games – Vandy pitched 3⅓ more hitless innings until Debs Garms hit a single. That ended his hitless string at 21⅔ innings.

Vander Meer was glad it was over. “The pressure had become too much and I was glad to get out from under it. Enough was enough,” he said. “I think if I’d have had a $10 bill in my baseball pants I’d have gone over to first base and handed it to Garms.”23 The Reds won 14-1 and Vandy had allowed four hits.

On the basis of his nine-game winning streak with the no-hitters sandwiched in between, Vander Meer was selected to be the starting pitcher in the annual All-Star Game, this one at his home park, Crosley Field. He pitched three scoreless inning and gave up only one hit, to Joe Cronin. In addition to Cronin, the American League lineup featured Charlie Gehringer, Jimmy Foxx, Joe DiMaggio, Bill Dickey, and Lou Gehrig. The American Leagers were impressed. “He’s wicked,” said DiMaggio.24 The National League lost 4-1.

Vander Meer finished the season 15-10 with an ERA of 3.12, striking out 125 and walking 103. He was named The Sporting News’ Major League Player of the Year.

The Reds had high hopes for Vander Meer in 1939. But it was not to be. A series of illnesses and arm troubles put a crimp in his pitching, although probably for sentimental reasons he was selected to again appear in the All-Star Game. He finished the season 5-9 with a 4.67 ERA. The Reds reached the World Series, but the Yankees swept them. Vander Meer didn’t pitch an inning.

The 1940 season was not much better. He was sent down to pitch at Indianapolis in the middle of the year with the hope that he could return to help the Reds to another pennant. And that he did. He came back in September, pitched a couple of good games, and then Bill McKechnie picked him to pitch against the Phillies on September 18 in a game that could clinch the pennant. He pitched 12 innings of the 13-inning game and scored the tiebreaking run of the 4-3 game on a sacrifice fly.

Vander Meer was hoping to start a World Series game, but McKechnie used him only in relief. He pitched three scoreless innings in Game Five. The Reds beat the Tigers in seven games.

The next year Vandy ran up a 16-13 record with a 2.82 ERA with a one-hitter thrown in, on June 6, when he shut out the Phillies, 7-0. “It was the best game he ever pitched,” catcher Ernie Lombardi said. Except for a disputed scratch hit, Vander Meer would have had his third no-hitter.25 On August 20 Vander Meer was half of a pitching duo that accomplished a rare feat in a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Phillies. He and Elmer Riddle threw back-to-back shutouts, Vandy winning 2-0 and Riddle 3-0. That feat had been accomplished only 39 times in the American League and 58 in the National League since 1900. That was followed by an 18-12 year and then 15-16. In 1943 Vander Meer and Riddle matched their 1941 feat with another doubleheader in which they blanked their opponents, this time the Boston Braves on September 26. Riddle won the first game this time, 2-0, and Vander Meer the second, 1-0 – only the second time ever that the same two pitchers accomplished this feat.26

Vander Meer made the National League All-Star Games again in 1942 and ’43. In 1944-45, during World War II, he served in the Navy, joining other major leaguers who played in all-star games to entertain US troops.

After the war ended and he returned to baseball, Vander Meer was pretty much a mediocre pitcher, with a record of 44-55 with three teams. He was traded to the Chicago Cubs in 1950 and joined the Cleveland Indians in 1951 after being released by the Cubs. He was 3-4 with the Cubs and in one appearance for the Indians, he gave up six runs in three innings and was released.

Vander Meer’s career major-league record was 119-121. He walked 1,132 batters and struck out 1,294. He pitched 30 shutouts. Over the years he received little consideration for the Baseball Hall of Fame.

He spent the rest of 1951 pitching for Oakland in the Pacific Coast League, where his record was 2-6 in 13 games. Vandy was out of baseball at the age of 37, but then Gabe Paul, the Reds’ general manager, offered him a contract to pitch and be the pitching coach for Tulsa in the Double-A Texas League. Vander Meer saw it as a chance to get back to the major leagues. He finished the season 11-10 with a 2.30 ERA, including a no-hitter. Still no big league team picked him up.

He continued to manage for 10 years, mostly with teams in the South. Then family pressures led him to retire from baseball for good. “I enjoyed the hell out of [baseball],” he said, “but I had to get into the business world.”27 Among the players he managed who became notable major-league players were Pete Rose, Jim “The Toy Cannon” Wynn, Jim Maloney, and Lee May.

After baseball Vander Meer worked for Schlitz Brewing Co. for 15 years. He also spent time playing in old-timer’s games, attending autograph signings, and fishing. He died on October 6, 1997, in Tampa, Florida, at the age of 82. He was preceded in death by his wife and two daughters. He was survived by a sister and two grandchildren. He was buried holding a baseball in his left hand.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 James W. Johnson, Double No-Hit: Johnny Vander Meer’s Historic Night under the Lights (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 89-91, 98-99.

2 Ibid., 31.

3 Cynthia J. Wilber, For the Love of the Game: Baseball Memories From the Men Who Were There (New York: William Morrow, 1992), 141.

4 Johnny Vander Meer and George Kirksey, “Two Games Don’t Make a Pitcher,” Saturday Evening Post, August 17, 1938, 41.

5 Johnson, 35.

6 Kansas City Star, May 29, 1983.

7 Newspaper clipping, June 23, 1938. Vander Meer file, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

8 Paterson (New Jersey) Evening News, June 18, 1938.

9 New York World-Telegram and Sun, July 6, 1938.

10 Gordon Campbell, Famous American Athletes Today, Ninth Series (Boston: L.C. Page and Co., 1945), 53.

11 Johnson, 53.

12 The Sporting News, November 5, 1936.

13 Washington Post, March 4, 1959.

14 Atlanta Constitution, January 24, 1937.

15 Johnson, 58-59.

16 Vander Meer and Kirksey, 43.

17 United Press International, September 19, 1940.

18 Vander Meer and Kirksey, 44.

19 New York World-Telegram, January 28, 1939.

20 North American Newspaper Alliance, January 6, 1939.

21 From video included in James Buckley, Jr. and Phil Pepe, Unhittable: Reliving the Magic and Drama of Baseball’s Best-Pitched Games (Chicago, Triumph Books, 2004).

22 New York Times, June 17, 1938.

23 David N. Keller, “Oh, Johnny: Forgotten Baseball Legend,” Timeline (a publication of the Ohio Historical Society), March/April 1999, 42.

24 Associated Press, July 7, 1939.

25 International News Service, April 30, 1941.

26 James Watkins and Paul Doherty, “The Double Whammy,” Baseball Research Journal, 4 (1975); http://research.sabr.org/journals/double-whammy

27 Bill Ballew, “Johnny Vander Meer Discusses His Baseball Career,” Sports Collectors Digest, May 25, 1990, 245.

Full Name

John Samuel Vander Meer

Born

November 2, 1914 at Prospect Park, NJ (USA)

Died

October 6, 1997 at Tampa, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.