Closing the Gap: The MVP Cases for Lew Fonseca, Joe Cronin, and Hack Wilson

This article was written by John Racanelli

This article was published in Fall 2024 Baseball Research Journal

On May 7, 1929, the American League announced it had abolished the “League Award,” the most valuable player honor that it had awarded annually since 1922, ostensibly because “it tended to create ill-feeling among the players.”1 The National League followed suit on June 8, eliminating its League Award, which had been given annually since 1924, citing similar reasons.2 James Long of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph heralded the move, writing, “‘The most valuable player’ stuff was the bunk and never did anything but harm the game, inasmuch as it gave the favored player an exaggerated idea of his importance and created petty jealousies on the team.”3

The leagues’ dubious public justifications sparked skepticism, and speculation swirled that the magnates had grown weary of the players who finished high in the MVP voting holding out for higher salaries.4 The leagues were also able to save the $1,000 cash payout (approximately $18,000 today) that accompanied each award. The AL gave no award in 1929. The NL stopped after giving Chicago Cubs second baseman Rogers Hornsby his second MVP that year.5

The Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA) took over voting in 1931 and has chosen a Most Valuable Player for each league ever since, which leaves an awkward gap between the end of the league awards and the current incarnation of the award: Three MVP seasons are unfairly ignored. Following each of those seasons, however, polling was completed by the sportswriters and a record of the voting results was published contemporaneously.6 Accordingly, crowning the consensus Most Valuable Player for each of these three league-seasons—Lew Fonseca, Joe Cronin, and Hack Wilson—is reasonably straightforward.

THE CHALMERS AWARD

The idea of a most valuable player award originally grew from a promotion sponsored by the Chalmers-Detroit Automobile Company, which offered a new car to the player who posted the highest batting average in 1910.7 Owner Hugh Chalmers, “an enthusiastic baseball booster,” was perhaps hoping to simply hand the car over to hometown Tiger Ty Cobb, who had won the past three batting titles.8

The 1910 AL batting race, however, ended in controversy (and a lawsuit!) as manager Jack O’Connor and the St. Louis Browns were accused of purposely allowing Cleveland’s Napoleon Lajoie seven bunt hits in a season-ending doubleheader to wrest the batting crown from Cobb.9 Ultimately, Chalmers ended up giving away two cars—one each to Cobb and Lajoie— after league president Ban Johnson declared that Cobb had actually won the batting title over Lajoie, .384944 to .384084.10

In 1911, Chalmers announced a modified scheme by which his company would give a car “to each of two players, one in the National League and one in the American League, who do the most to help their respective teams.”11 Connie Mack telegraphed Chalmers praising the plan to reward “the most valuable ball player in each league,” perhaps unintentionally coining the term for the leaguewide honor.12 Chalmers thereafter tasked a committee of baseball writers to determine the winner for each league.13 The Chalmers Company awarded cars to a pair of players through the 1914 season, then abruptly ended the contest, claiming that the plan all along had been to run the promotion for five years.14

THE LOST YEARS

When the American League revived the idea to select a most valuable player in 1922—accompanied by a $1,000 cash reward—the owners imposed two conditions: (1) no player-managers were eligible because of the influence they might impose on game action; and (2) no repeat winners.15 The initial plan called for a commission of newspaper men in each league city and a chairman “not actively connected with baseball” to select a player on the basis of “all-around ability, faithfulness, and freedom from accident, sickness, etc.”16 The National League considered establishing an MVP award of its own in 1922 but did not make the award official until 1924, without any restrictions imposed on player-managers or repeat winners.17

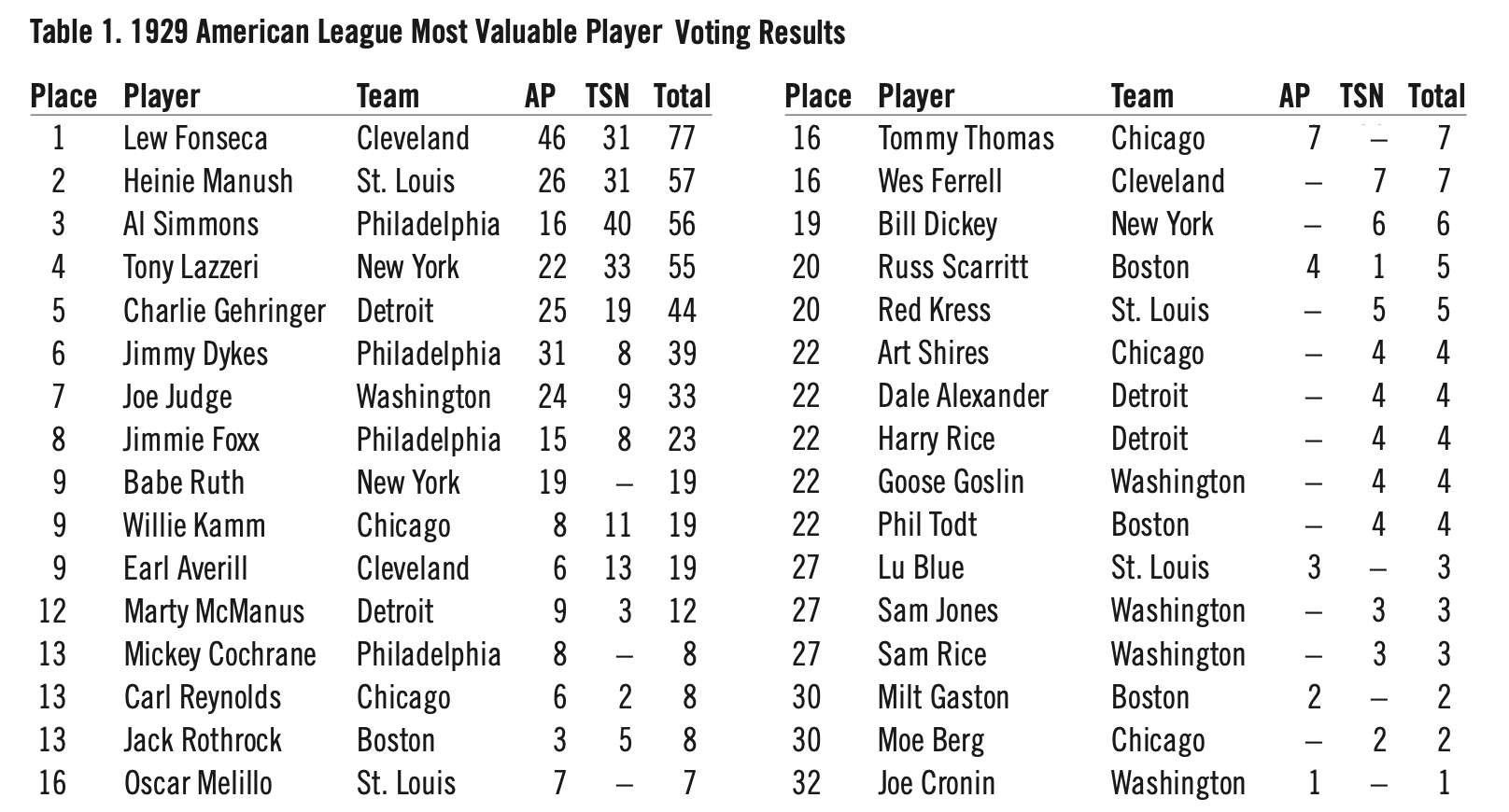

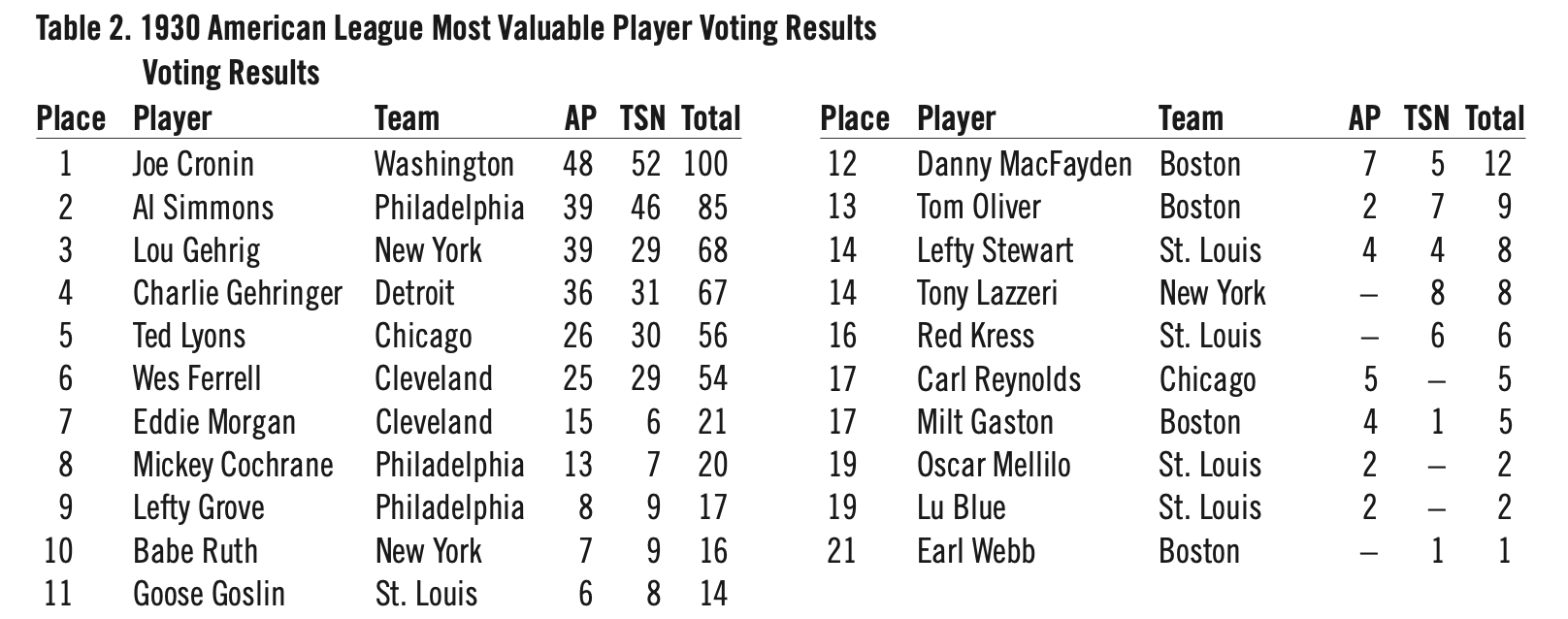

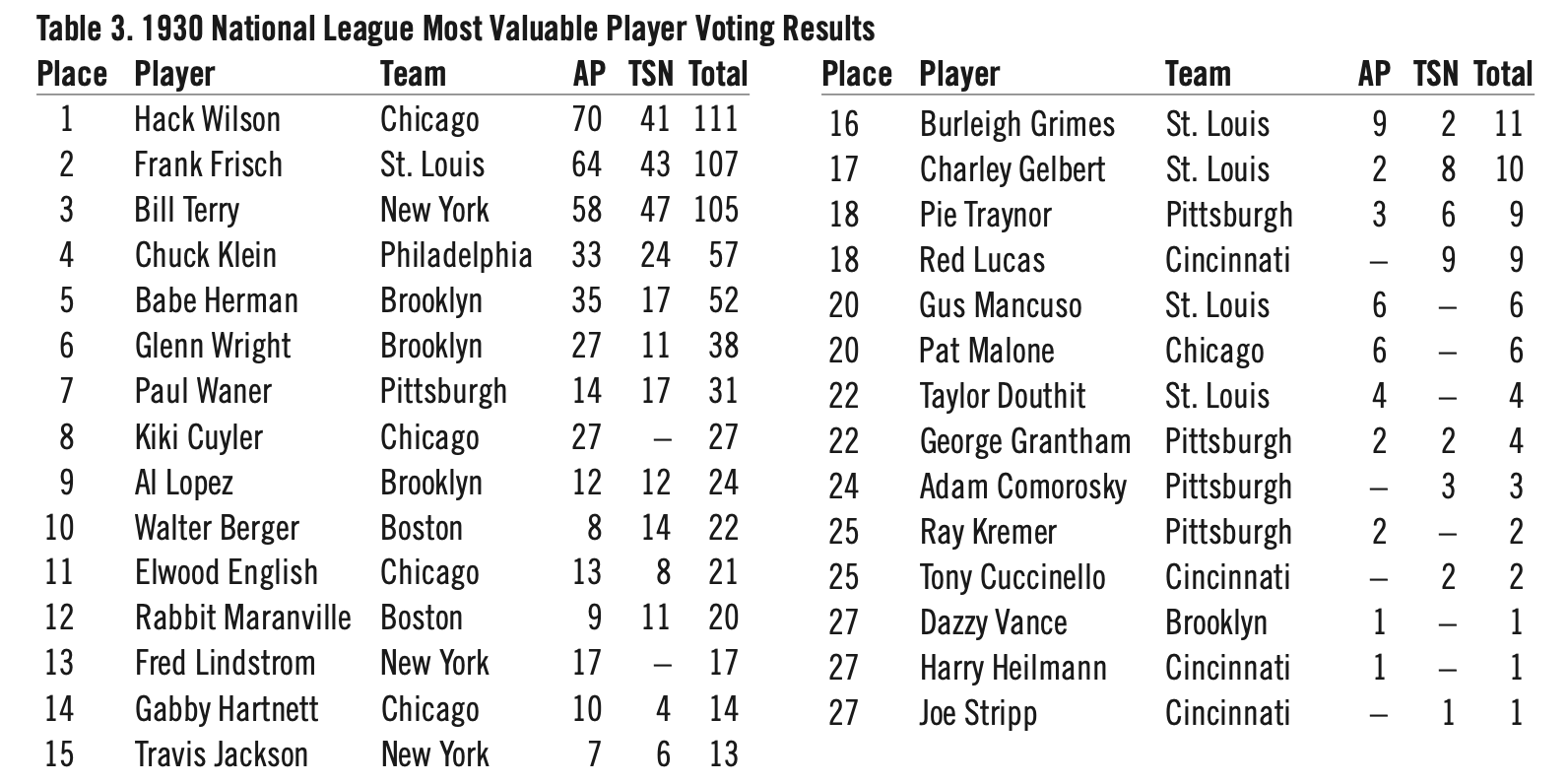

Despite the American League’s decision to discontinue the MVP selection in 1929, the Associated Press assembled a committee that included a baseball writer from each of the eight league cities to vote. The polling was conducted in precisely the same manner as in previous years: a first-place vote was worth eight points, a second-place vote seven points, and so on. The Sporting News also named Most Valuable Players in those years using a similar slate of writers: Al Simmons was crowned the 1929 American League MVP, Joe Cronin was christened 1930 American League MVP, and Bill Terry was named 1930 National League MVP. The transparent nature of the processes undertaken by the Associated Press and The Sporting News makes it possible to determine the consensus MVP for each of these years.

Lew Fonseca, 1929 American League MVP (SABR-Rucker Archive)

1929 AMERICAN LEAGUE MVP: LEW FONSECA (CLEVELAND)

Lew Fonseca was a man of many talents: licensed dentist, accomplished singer, ping-pong aficionado and “expert card manipulator.”18 Following four seasons with the Cincinnati Reds and one with the Philadelphia Phillies from 1921–25, Fonseca found himself with the Newark Bears in the International League in 1926. After batting .381 with 21 home runs for Newark, Fonseca was traded to the Cleveland Indians.

Playing at all four infield positions for Cleveland in 1928, Fonseca garnered enough support to place 22nd in MVP voting, despite having only appeared in 75 games. Fonseca was installed as Cleveland’s first baseman the following season and flourished, leading the AL with a .369 batting average and setting career marks in hits (209), runs (97), doubles (44), triples (15), runs batted in (103), and stolen bases (19).

Following the 1929 season, the Associated Press committee crowned Fonseca as American League MVP with 46 points.19 Cleveland’s general manager, Billy Evans, celebrated Fonseca’s win by giving him a check for $1,000 to replace the reward the AL had discontinued.20 (The subsequent Sporting News vote placed Fonseca in a third-place tie with 31 points.)21 The complete results are shown In Table 1.

Fonseca had received two points in the 1928 Most Valuable Player voting, but never received another vote for the remainder of his career.

1930 AMERICAN LEAGUE MVP: JOE CRONIN (WASHINGTON)

Nineteen-year-old shortstop Joe Cronin smacked his first big-league hit for the Pittsburgh Pirates on August 4, 1926. In September, he took over as starting second baseman and things looked bright for the youngster. However, personnel changes prior to the 1927 season conspired to keep Cronin on the bench and he appeared in just 12 games for the Pirates, despite being with the club for the entire season. He was sold to the American Association Kansas City Blues on April 1, 1928 and played half a season there before Washington purchased his contract in July. Cronin claimed the starting shortstop job in 1929 and had a nice season, which included an MVP vote following the campaign.

Cronin blossomed in 1930, batting a career-high .346, leading the league with 154 games played, and setting career highs in runs (127), hits (203), runs batted in (126), stolen bases (17), and total bases (301). Washington improved from 71–81 and a fifth-place finish in 1929 to 94–60 and second place in 1930.

Following the season, the appointed committee of baseball scribes chose Cronin as the American League MVP as he garnered one vote for first place, four votes for second place, and one each for fourth, fifth, and sixth.22 (The subsequent Sporting News vote also placed Cronin first with 52 points.)23 The complete results are shown in Table 2, below.

Cronin collected MVP votes in seven subsequent campaigns, finishing as high as fifth. However, this 1930 Most Valuable Player Award would be the only one of his Hall of Fame career.

1930 NATIONAL LEAGUE MVP: HACK WILSON (CHICAGO)

Lewis Robert “Hack” Wilson was famously “built like a beer keg and not unfamiliar with its contents.”24 Following a relatively undistinguished start to his major-league career with the New York Giants, Wilson was sent by John McGraw to the American Association Toledo Mud Hens in 1925. He was left unprotected, and the Chicago Cubs selected him in the 1925 major league draft. As Chicago’s center fielder from 1926–29, Wilson led the NL in home runs three times and finished third once.

In 1930, Wilson appeared in 155 games for the Cubs and set career highs for runs (146), hits (208), home runs (56), runs batted in (191), base on balls (105), batting average (.356), on-base average (.454), slugging percentage (.723), and total bases (423), and his OPS of 1.177 is still a single-season Cubs record. The 191 runs batted in remain a major-league record, perhaps belonging in the conversation about unbreakable marks (see Table 3, opposite).

Wilson received Most Valuable Player votes in five other seasons, finishing as high as fifth in 1926. This 1930 MVP Award would be the only one of his Hall of Fame career.

HONORING LEW, JOE, AND HACK

While hitters love to find gaps, baseball historians prefer to close them. Official recognition of the Most Valuable Player campaigns of Fonseca, Cronin, and Wilson would provide an uninterrupted line of MVP awards reaching back to the 1920s for each league. This awkward gap could be closed.

At its core, the only true difference in American League MVP voting between 1928 and the 1929–30 seasons was the league’s withdrawal of the $1,000 cash reward. Same for the National League in 1930—the only season since 1924 in which a league MVP is not recognized.

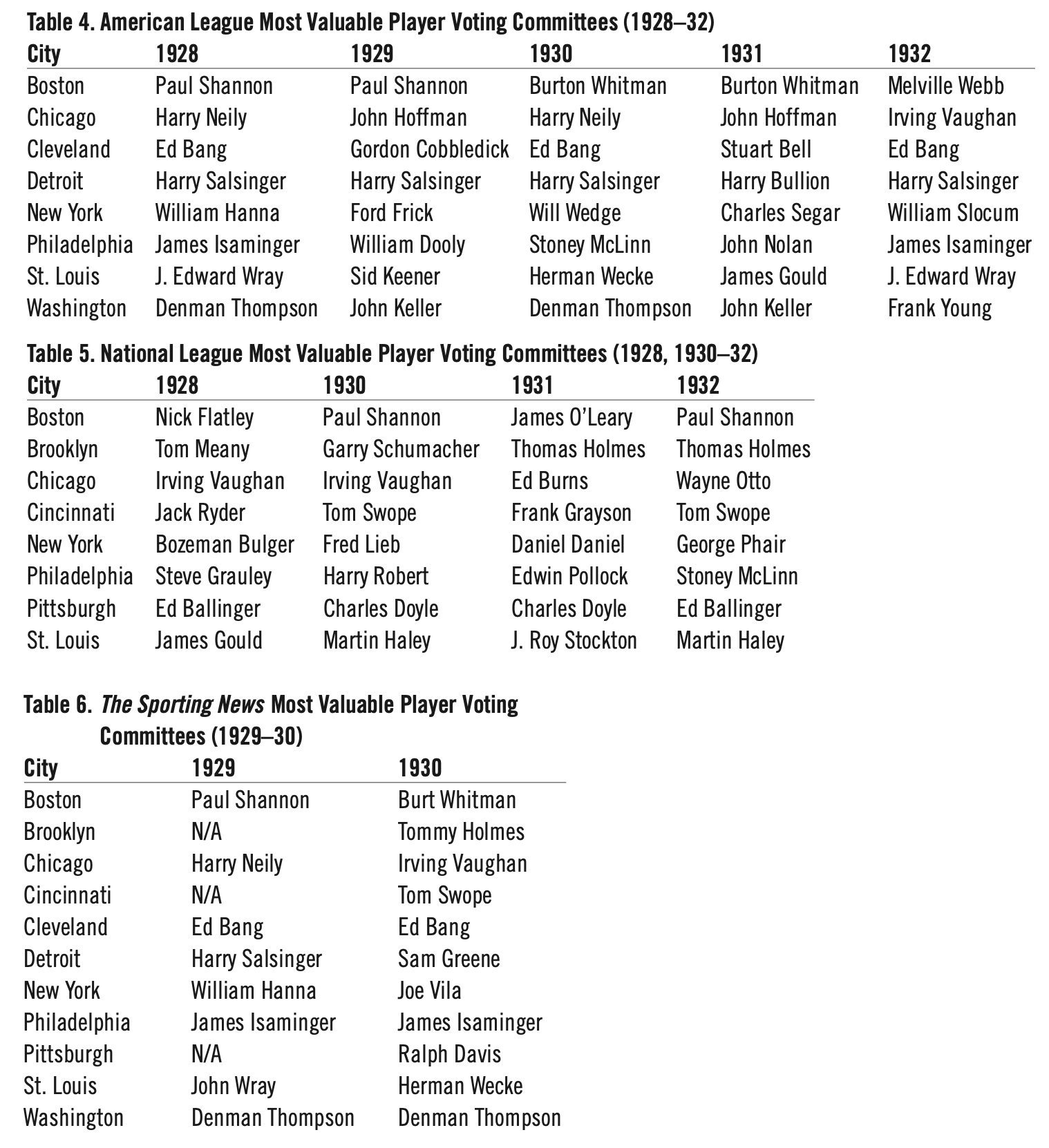

American League MVP voting was handled in the same manner in 1929 and 1930 as it was done for the officially recognized league awards through 1928 (one writer representing each of the eight AL cities casting a ballot of eight players for a maximum total of 64). There were several baseball writers who voted in 1929 and/or 1930 who cast MVP votes before and after, as shown in Table 4, below.

Similarly, the National League vote for 1930 was handled in the exact same manner as it had been in 1924–29 (one writer representing each of the eight NL cities casting a ballot of 10 players for a maximum total of 80). Again, there were several voters in 1930 who participated in the MVP selection process both before and after (see Table 5, below).

The Sporting News voting committees for 1929 and 1930 are shown below. The published list of voters for 1930 was combined, which tends to indicate that the writers for two-team cities participated in both the AL and NL voting. There was considerable overlap between this group and writers involved with the Associated Press MVP selection committees held earlier in each year (Table 6).

Starting in 1931, the BBWAA began voting for league MVPs, adopting the system previously used to select the National League winners: 10 points for first place, nine points for second place, and so on, for a maximum of 80.25 Nevertheless, the Most Valuable Player selections for 1931 through 1934 were deemed “unofficial” in contemporary reporting.26 When the 1935 MVP awards were announced for Hank Greenberg of Detroit in the AL and Gabby Hartnett of Chicago in the NL, however, the selections no longer included the “unofficial” modifier.27 The BBWAA used this system for MVP voting through 1937. In 1938, the voting system was expanded to include three writers from each city in each league and the ballot enlarged to 14, for a maximum vote total of 336.

Baseball and fans alike should recognize and celebrate these Most Valuable Player campaigns, especially considering that the MVPs for Fonseca, Cronin, and Wilson would be the only such award for each man. Indeed, the plaque honoring Cronin at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown prominently heralds his selection as the American League Most Valuable Player in 1930! It is time to close the gap.

JOHN RACANELLI is a Chicago lawyer with an insatiable interest in baseball-related litigation. John is membership director for the Chicago SABR Chapter and founder of the SABR Baseball Landmarks Research Committee. A regular contributor to the SABR Baseball Cards Research Committee, his “Death and Taxes and Baseball Card Litigation” series of articles was a 2023 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award winner.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to extend special thanks to Mark Armour, Ryan Fagan, Steve Gietschier, Bill Deane, and Adam Darowski for their kind direction and encouragement.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the endnotes, the author also utilized: Armour, Mark, “Joe Cronin,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/joe-cronin/.

Baseball Reference (which now recognizes these MVP campaigns). Gabcik, John, “Lew Fonseca,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/lew-fonseca/.

Retrosheet.org.

NOTES

1 “A.L. Abandons Most Valuable Player Award,” Decatur (IL) Herald, May 7, 1929, 12. AL MVP Award winners: 1922: George Sisler, St. Louis; 1923: Babe Ruth, New York; 1924: Walter Johnson (Washington); 1925: Roger Peckinpaugh, Washington; 1926: George Burns, Cleveland; 1927: Lou Gehrig, New York; 1928: Mickey Cochrane, Philadelphia.

2 “National No Longer Will Give Awards,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 8, 1929, 17. NL MVP Award winners: 1924: Dazzy Vance, Brooklyn; 1925: Rogers Hornsby, St. Louis; 1926: Bob O’Farrell, St. Louis; 1927: Paul Waner, Pittsburgh; 1928: Jim Bottomley, St. Louis; 1929: Hornsby, Chicago.

3 James Long, “Sports Comment,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, May 7, 1929, 20.

4 Murray Robinson, “As You Like It,” Brooklyn Standard Union, May 7, 1929, 14.

5 The National League had no rule preventing a player from winning multiple awards. Hornsby had also been voted NL MVP in 1925 with St. Louis.

6 The Associated Press and The Sporting News held separate votes in 1929 for the American League and in 1930 for the American League and National League.

7 “Auto for Best Batsman,” The New York Times, March 1, 1910, 10.

8 “Baseball for Hugh Chalmers,” Detroit Free Press, March 2, 1910, 14.

9 O’Connor v. St. Louis American League Baseball Co., 181 S.W. 1167, 193 Mo.App. 167 (Mo. App. 1916).

10 “Chalmers Felicitates Cobb,” Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1910, 22; “Cobb Wins Title and Auto,” Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1910, 22. Some simple math seems to indicate that the 196 hits in 509 at-bats credited to Cobb at the time resulted in a .385069 batting average and Lajoie’s 227 hits in 591 at-bats would have been .384095. Regardless, baseball historians have thoroughly reexamined these records and Baseball Reference now lists Lajoie with a .383 batting average (227 hits in 592 at-bats) and Cobb with a .382 batting average (194 hits in 508 at-bats.) Both are credited with the batting title on the website.

11 “Mack Approves Chalmers’ Plan,” Altoona (PA) Times, February 14, 1911, 9.

12 “Mack Approves Chalmers’ Plan.” At least as far back as 1875, the concept of most valuable player to his ballclub was recognized with the first documented use tied to a silver trophy given to Deacon White by a wealthy supporter engraved with the caption “Won by Jim White as most valuable player to Boston team, 1875.” Peter Morris, A Game of Inches (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010), 541, citing Bill Deane, Award Voting, 5–6.

13 “Hugh Chalmers Would Stimulate Batting Averages,” Lansing State Journal, February 3, 1911, 8.

14 “No More Free Autos for the Ball Players,” Pittsburgh Press, December 27, 1914, 22. Winners of the Chalmers Award: 1911: Ty Cobb, Detroit (AL), Frank Schulte, Chicago (NL); 1912: Tris Speaker, Boston (AL), Larry Doyle, New York (NL); 1913: Walter Johnson, Washington (AL), Jake Daubert, Brooklyn (NL); 1914: Eddie Collins, Philadelphia (AL), Johnny Evers, Boston (NL).

15 “League Offers $1000 Reward for Player,” Baltimore Sun, February 9, 1922, 11. Ty Cobb was ineligible for consideration as the Tigers’ player-manager in 1922, despite batting .401/.462/.565 in 613 plate appearances.

16 “League Offers $1000 Reward for Player.”

17 “Older League Meeting Ends in Love Feast,” Freeport (IL) Journal-Standard, February 15, 1922, 8.

18 Mark Dukes, “AL Batting Champ Earned $1000 Raise,” Cedar Rapids Gazette, April 9, 1989, 32.

19 Alan Gould, “Lew Fonseca is Named Most Valuable Player in A.L. by Sport Scribes,” Appleton (WI) Post-Crescent, October 16, 1929, 12.

20 “Lew Fonseca Gets $12,000 Check in 1930,” Stockton Daily Evening Record, December 16, 1929, 25.

21 “Simmons ‘Most Valuable’ Player in American League,” Joplin (MO) Globe , December 25, 1929, 10.

22 “Joe Cronin Beats out Simmons and Gehrig,” Boston Globe, October 10, 1930, 25.

23 “Cronin and Terry Named as Most Valuable Players,” The Sporting News, November 27, 1930, 5.

24 Ron Coons, “A Tale of Two Sluggers,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 7, 1977, C-4.

25 “Writers to Pick Valuable Player,” Detroit Free Press, April 14, 1931, 28; “Flash Best,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 21, 1931, 14.

26 “Previous Winners of American Loop Title of ‘Valuable’ Player,” Rock Island (IL) Argus, October 28, 1931; “1932 Sport Champions,” Staunton (VA) Daily News Leader, December 30, 1932, 6; “Sport Champions of 1933,” Eugene Guard, December 31, 1933, 8; “Champions of the Sports World During 1934,” Oakland Tribune, December 31, 1934, 10.

27 “International Amateur and Professional Sports Champions of 1935,” Hackensack Record , December 31, 1935, 15.

28 Bill Terry’s Hall of Fame plaque also includes a reference to his 1930 Sporting News Most Valuable Player Award.