‘Viva, Valenzuela!’ Fernandomania and the Transformation of the Los Angeles Dodgers

This article was written by Jason Scheller

This article was published in Dodger Stadium: Blue Heaven on Earth (2024)

In May of 1957, Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley took a helicopter ride over Chavez Ravine, the eventual home of his iconic new ballpark. In Brooklyn he had loaded the team with Italian and African American players to reflect the demographics of that borough. He wanted his team to reflect the large Mexican American population in Los Angeles, so he put the word out to his scouts to find him the Mexican Sandy Koufax. While seemingly impossible to many in the Dodgers organization, the team’s longtime Spanish language broadcaster Jaime Jarrin said, “He had a vision. He knew that eventually that market would grow and would be a very important part of the business for the Dodgers.”1

Though he would not live to see Fernando Valenzuela’s Dodgers debut – O’Malley died in 1979 – his dream became a reality when the Mexican native was signed by Dodgers scout Mike Brito in 1979. The left-hander was sent to Lodi of the Class-A California League. Valenzuela worked with Dodgers reliever Bobby Castillo to develop an off-speed pitch that eventually became the screwball. He picked it up faster than anyone in the Dodgers organization could have imagined. Called up to the majors on September 15, 1980, Valenzuela made 10 relief appearances. He pitched 17⅔ scoreless innings with a 0.00 ERA mostly in relief for the Dodgers’ playoff run, which was ended by the Houston Astros in a one-game tiebreaker for the National League title.2

Valenzuela came to Los Angeles when it boasted the highest concentration of Mexican Americans in the world. Approximately 2 million of the 7½ million residents of Los Angeles County were of Mexican American descent.3 While there had been Mexican American or Dominican players for the Dodgers, including Bobby Castillo, José Peña, Sergio Robles, and Manny Mota, none had the impact that Valenzuela had, and Mexicans for the most part stayed away from Dodger Stadium. The 1981 season finally brought the Dodgers the player they had been hoping for and ignited a passion among the Mexican American population as one of their own was finally taking the mound at Dodger Stadium.

On Opening Day in 1981, the Dodgers found themselves in the peculiar position of needing a starting pitcher. Jerry Reuss, the 1980 National League Cy Young Award runner-up and the ace of the Dodgers’ rotation, was a late scratch because a calf muscle he had strained the day before left him unable to walk. The number-two starter, Burt Hooten, had just had a procedure to remove an ingrown toenail, which took him out of contention for the starting job. The third man in the Dodgers’ rotation, Bob Welch, was recovering from a bone spur in his right elbow; and the two men at the bottom of the rotation, Dave Goltz and Rick Sutcliffe, were healthy scratches. Both had pitched in an exhibition series against the California Angels before the season opener.4 That left Valenzuela as the lone option to start against the formidable Astros.

Additionally, the Astros had acquired former Dodgers pitching great Don Sutton in the offseason, a move that Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda seemed to take in stride: “We knew there was a possibility of losing Don Sutton (who played out his option and signed with Houston as a free agent), so we had to plan ahead.” Speaking of Valenzuela, Lasorda said, “We were looking at him as the replacement for Don.”5

Valenzuela was 20 years old and the first rookie to start on Opening Day in the team’s history. Many in the crowd of 50,511 had to wonder why he was pitching. He warmed up, then went into the training room for a nap before jogging out to the bullpen and then onto the field as the Opening Day festivities got underway.

Making the situation arguably more comical, Valenzuela threw a screwball, a pitch that no one else had thrown with regularity since Carl Hubbell in the 1930s. Hubbell used that pitch in the 1934 All-Star Game to strike out, in order, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons, and Joe Cronin, all future hall of famers.6 Regarding Valenzuela, Hubbell, who had retired in the 1940s, told reporters, “He’s got the best screwball since mine.”7

Valenzuela was opposed by Joe Niekro, who had pitched the Astros to a 7-1 victory in the 1980 tiebreaker.8 The Astros were unfazed by Valenzuela. “When we heard that Reuss wasn’t going to start and that we were going up against a rookie, we felt we had a much better chance against [Valenzuela] than the veteran All-Star,” said Houston pitcher Joe Sambito.9

The Astros were ready to pounce on the largely untested rookie, but they were in for a surprise. Valenzuela’s delivery befuddled them. With his hands clasped, he reached toward the sky, while simultaneously lifting his right leg and his eyes toward the heavens, as if to ask for divine intervention, before delivering his pitch. Valenzuela threw a screwball to Astros leadoff hitter Terry Puhl, who hit a grounder to shortstop for the first out of the game. Valenzuela proceeded to pitch an almost flawless game, coaxing Astros hitters into groundballs, or occasional singles, but not giving up a run. He fanned Dave Roberts on a screwball for the final out to complete a five-hit, 2-0 shutout.10

Speaking of his screwball afterward, he said, “That’s my pitch, and when I need the big outs that’s what I go to.”11 While that victory provided a measure of retribution for the playoff loss in 1980, the game is better remembered as the birth of “Fernandomania.” It marked the beginning of a string of victories that made Valenzuela the star of the league and a hero to the legions of Dodgers fans the world over. Sportswriter Paul Oberjuerge summed up fans’ feelings when he stated, “Enroll me in the Fernando Valenzuela fan club. Any guy who can get people out despite that Pillsbury Doughboy physique is all right in my book.”12

That first win also ignited the local Mexican American community in Los Angeles, who wanted to see someone who reflected their background pitch for the Dodgers. That same community had once sworn not to attend Dodgers games when the ballpark opened in 1962 because of the way the evictions for the remaining Chavez Ravine families had been handled in 1959. The win would, in the words of Erik Sherman, “spark a phenomenon in which this remarkable young Mexican pitcher would begin to heal a long-fragmented relationship between the Dodgers, the city of Los Angeles, and a largely marginalized Latino community.”13

After the Opening Day series against Houston, the Dodgers went on the road. When Valenzuela’s second start came around, they were 4-0 and off to their fastest start since 1955. Unfazed by the frigid winds of Candlestick Park, Valenzuela pitched another gem of a game, allowing four hits and striking out 10 in a 7-1 victory over the Giants. He gave up a run, which he hadn’t done since his time with San Antonio in the minors. “I didn’t get tired, but I was a little stiff the last few innings because of the cold,” Valenzuela said.14

His next game was on April 18, in San Diego. The Dodgers won 2-0. Valenzuela pitched a five-hit shutout to improve his record to 3-0. Since his debut in September the season before, Valenzuela had allowed just one run in 44⅔ innings pitched. The win gave Valenzuela his second shutout and third straight complete game of the season. Valenzuela spoke modestly of his performance after the game, saying, “I don’t know if this is a streak. I’ve always pitched like this.”15

His next start came against Houston in the Astrodome. Before a crowd of 22,830, Valenzuela faced off against the man he was brought to Los Angeles to replace, Don Sutton. Both pitched well. While Sutton scattered six hits and allowed one run over seven innings, he was no match for the Dodgers phenom. Valenzuela threw yet another complete game, with 11 strikeouts en route to a seven-hit shutout. He also supplied his own run support, slapping a single off Sutton in the fifth inning to score Pedro Guerrero for the only run of the game. “When I got the hit, I was pleased to get the hit, but thankful to get ahead in the game,” Valenzuela said.16 With the win, Valenzuela now led the league in wins (4), strikeouts (36), complete games (4), shutouts (3), and innings (36), with an ERA of 0.25.17 Speaking of Valenzuela after the game, Sutton said, “He’ll come back to earth someday and give up an earned run or two.”18

Valenzuela returned April 27 to a hero’s welcome at Dodger Stadium. Throngs of fans burst through the turnstiles to welcome him back home against the Giants. The Dodgers hired Spanish-speaking ushers, and many in the crowd waved Mexican flags. Vendors hawked Fernando Valenzuela paraphernalia, mariachi bands played, and Mexican Americans showed up in force to support their freshly adopted favorite. “The fan demographics of Dodger Stadium changed in a month,” said Peter Schmuck. “It was stunning to pull your car into the parking lot and drive by mariachi bands. Sure, Mexican Americans came to games, but not like that. It was so much fun, just a wonderful, unbelievable circus.”19 Pitching in front of 49,478 fans, Valenzuela gave them what they came to see, beating the Giants 5-0 to secure his fifth straight victory and fourth shutout. “Webster has no words to define him,” Dodgers second baseman Davy Lopes said. “He owns this city right now. He’s entitled to all this acclaim. He’s a super kid and a great pitcher.”20

While Valenzuela’s seven strikeouts catapulted him to first place in the National League with 43, and the seven hits in his past 11 plate appearances ballooned his batting average to .438, it all paled in comparison to the woman who ran onto the field that night. In the ninth inning, Norma Echevarra, a young Mexican American woman wearing a “Valenzuela 34” raglan T-shirt. grasped Valenzuela’s shoulders and kissed him on the right cheek. Afterward, she raised her arms into the air and jumped up and down on the pitcher’s mound before being escorted from the ballpark by security.

Echevarra’s kiss was symbolic of the Mexican American community’s recognition of Valenzuela. It became, in the words of Erik Sherman, “a lasting image and symbol of the love and adoration being bestowed by millions of Mexican and other Latino fans on their new hero – Fernando Valenzuela.”21 Her kiss was emblematic of the transformative effect he had on the Dodger fanbase.

While the Dodgers possessed other high-profile pitchers, Valenzuela outdrew all of them in 1981. At home he drew an average 48,431 while everyone else on the pitching staff drew 40,941. For road games he pitched in, he averaged 32,273 people in attendance while other Dodgers pitchers garnered 14,292, a difference of 18,981.22 The Dodgers’ veteran Spanish-language announcer Jaime Jarrin summarized Valenzuela’s effect best by saying, “I truly believe that there is no other player in major league history who created more new fans than Fernando Valenzuela. Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Joe DiMaggio, even Babe Ruth did not. Fernando turned so many people from Mexico, Central America, South America into fans. He created interest in baseball among people who did not care about baseball.”23

There were so many interview requests that the Dodgers were forced to hold pregame press conferences in the locker room of every ballpark they visited. Back in Los Angeles, fans bought Valenzuela T-shirts or made their own bootleg versions to sell. Newspapers were hungry for more stories about Valenzuela, and the local newspapers were cranking out stories about him, his mysterious beginnings, and every facet of his life as fast as they could. Even the Los Angeles Police Department became part of the mania, ordering 100,000 Dodgers baseball cards with the LAPD insignia to hand out to children in the areas they patrolled.24 “Everyone was clamoring for Fernando stories, and it was just so unbelievable the amount of attention he was getting,” said former Dodgers director of publicity Steve Brener. “I can’t remember one player who captured the fantasy of the fans and the media the way Fernando did.”25

With Fernandomania now in full swing, the Dodgers traveled north of the border to take on the Montreal Expos on May 3, 1981. Valenzuela retired 21 straight batters after allowing a single to start the game. In the eighth inning, Chris Speier hit a single scoring pinch-runner Tom Hutton to tie the game, 1-1. Up to that point, Valenzuela had gone 36 innings without allowing a run. Manager Lasorda brought in Reggie Smith to pinch-hit for Valenzuela in the top of the 10th inning, while the Expos stuck with Tom Gullickson, who gave up five runs in the 10th inning to give Valenzuela a 6-1 victory. Valenzuela was 6-0, and it was only the second time he had been scored upon all season. Lasorda put the momentous victory in perspective saying, “It’s good for the Dodgers, the city of Los Angeles, for the country of Mexico and for baseball all over.”26

Valenzuela pitched next at Shea Stadium against the New York Mets on May 8. Up to that point he had six games, six wins, and four shutouts while allowing only two earned runs. He also had become the biggest draw in the major league. The Mets’ attendance numbers certainly reflected that. “39,848 fans – not bad for a team that averaged 11,300,” said sports artist LeRoy Neiman, who was on hand to sketch Valenzuela’s portrait before the game.27

Fans at Shea Stadum, just like fans who watched Fernando at other ballparks, waved Mexican flags and many wore sombreros. Valenzuela had certainly had a profound effect on baseball in Los Angeles and Latino culture throughout the United States. “I really do believe Fernando’s significance, in terms of what he did to give Mexicans a feeling of belonging, and of telling Americans that ‘we’re here,’ was remarkable,” said José de Jesus Ortiz, the first Latino to serve as president of the Baseball Writers Association of America. “So, he took us out of the shadows and introduced us to a country that didn’t realize we were here in such large numbers.”28

With all the adoration heaped on the visiting Valenzuela, the Mets felt like strangers in their own stadium. “I get a little tired when I look up at our own scoreboard and see constant plugs for a visiting team and visiting pitcher,” said Mets manager Joe Torre.29 Many Mets players agreed with Torre. “I’m sure the kid’s doing a super job,” second baseman Doug Flynn said, “and you’ve got to respect him. But I’d like to see the Mets promote our own club instead of visiting players. We’d like to think we’ve got a good selling product, too. We don’t want all those people coming in here hoping the guy will shut us out.”30 The Mets finished 21 games under .500 in 1981. With no good news of their own to report they used other teams’ best players to promote their club.

Despite the Mets’ best efforts, Valenzuela pitched his fifth shutout of the season, striking out 11 and dropping his earned-run average to 0.29. The Dodgers won 1-0, and Fernando improved to 7-0. “I had no control the first three innings,” he said after the game. “I wasn’t following through. I was throwing straight. My screwball wasn’t breaking, and my fastball was out of the strike zone.”31 Valenzuela was now on pace to set the rookie record for shutouts, and it seemed possible to all who watched him pitch that he would do it. Valenzuela was asked if he could pitch his entire career undefeated. He wryly answered, “It is difficult, but not impossible.”32 The victory left Valenzuela one away from the record of eight consecutive wins to begin his rookie season set by Boston Red Sox rookie pitcher Boo Ferriss in 1945, and three shy of the all-time rookie shutout record set by the Chicago White Sox pitcher Reb Russell in 1913.33 Ferriss began his rookie season with the Boston Red Sox in 1945 pitching 22⅓ consecutive scoreless innings, over nine games, he recorded eight consecutive victories.34 While many attributed Ferriss’s success to facing lineups weakened by the absence of players in World War II, his manager, Joe Cronin, said, “That boy is no wartime ballplayer. He’d be outstanding in any era.”35

A week after the Mets game an action shot of Valenzuela pitching appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated with the caption “UNREAL” in block letters. It was the pinnacle of magazine covers for a professional athlete, reserved only for the best, and he had made it after only seven games! In that same week he appeared on the covers of Sport Magazine, The Sporting News, and Baseball Digest.

Valenzuela took the mound on May 14, 1981, against the Expos in a Thursday night game that had been sold out for a week. A crowd of 53,906, the most for a Dodgers regular-season home game since 1974, showed up to cheer on their new hero. To accommodate the large number of Mexican American fans, the Dodgers hired ushers who spoke Spanish. The flags flying in the crowd that night no longer represented just Mexico. “Every Latin American county seemed to be represented. Not only Mexico. I’m talking El Salvador, Nicaragua – there were so many different flags,” recalled Dusty Baker.36 Valenzuela seemed human for the first time in his career, giving up three hits and two runs. Pedro Guerrero hit a tie-breaking solo home run to win it for the Dodgers, 3-2. While Valenzuela’s record increased to 8-0, it was the first time he had pitched from behind all season, as well as the first time he had given up more than one run in a game. He now had eight consecutive wins, tying the rookie record set by Boo Ferriss in 1945, seven complete games, 68 strikeouts, and a 0.50 ERA. The game marked the first time Valenzuela’s incredible streak might be in danger of ending. “Right now, I’m winning, and I hope it continues. But if I do lose, I’m prepared to deal with it,” Valenzuela said.37

Pitching on three days’ rest, Valenzuela next appeared against the Philadelphia Phillies at Dodger Stadium. His parents had flown in from Mexico to see him pitch in front of 52,439 fans. Despite all that, Valenzuela lost his first game of the season thanks to a home run by Mike Schmidt and a three-run fourth inning that propelled the Phillies to a 4-0 victory over the Dodgers. “I don’t think it will affect me. You win some games, and you lose some games. Tonight, I just lost. That’s all there is to it,” Valenzuela said afterward.38 During the game, the LAPD received a teletype message from the Savannah, Georgia police department asking, “Could you advise how Valenzuela is doing?” After the game was over, the LAPD passed along the news that Valenzuela had lost to the Phillies, 4-0. A spokeswoman for the Los Angeles Police Department noted that it was not usual to use police communications for unofficial business.39

By June 11, 1981, Valenzuela’s record stood at 9-4. In his six starts after posting an 8-0 record he went 1-4 with a 6.16 ERA.40 Then a players strike deprived fans of Valenzuela’s magic until August 10, when the games resumed. Valenzuela, who was named the starting pitcher for the National League All-Star team, returned from the strike strong, pitching three shutouts and pushing his total to eight, tying Reb Russell’s record. Attendance again attested to Valenzuela’s popularity as 46,168 people turned out to watch the game on September 17 against the Atlanta Braves, despite competition from a televised pro football game.41 Valenzuela won four of his last nine starts and finished the regular season with a 13-7 record.

In the National League West Division Series against the Astros, the Dodgers came back from two games down to win the five-game series behind the brilliant pitching of Valenzuela. Game One was a pitchers’ duel for the ages as the Astros’ Nolan Ryan and Valenzuela faced off. The two did not disappoint, as a capacity crowd of 44,836 filled the Astrodome to watch Ryan pitch a two-hitter, walking one and striking out seven. Valenzuela equaled his effort, striking out six and walking two over eight innings. Each man gave up one run. In the top of the ninth, Jay Johnstone pinch hit for Valenzuela. Fernando was replaced by Dave Stewart, who gave up a two-run home run to Astros catcher Andy Ashby as Houston edged out the Dodgers, 3-1.

A sellout crowd of 55,983 filled Dodger Stadium to witness Game Four. Pitching on three days’ rest, Valenzuela held the Astros in check through eight innings before giving up one run on four hits to win the game, 2-1. “There was no way I was going to take Valenzuela out of the game in the ninth inning,” Lasorda said. “It didn’t even enter my mind.”42

The Dodgers beat the Expos three games to two in the League Championship Series. In Game Two Valenzuela found himself on the wrong side of a shutout, losing to the Expos 3-0. In Game Five, Valenzuela was masterful, pitching 8⅔ innings, scattering three hits, and allowing only one run. The game was famous for Rick Monday’s clutch two-out home run in the top of the ninth to give the Dodgers the victory, 2-1.43

After the victory over the Expos, the stage was set for the 11th World Series matchup between the Yankees and Dodgers. The Dodgers had been on the losing end of eight of the first 10, with the most recent one in 1978.44 In this one, the Dodgers came back from a two-games-to-none deficit to knock off the Yankees.

In Game Three of the World Series, Valenzuela pitched to his largest crowd ever as 56,236 fans, a team record, filled Dodger Stadium. Sandy Koufax threw out the first pitch to a chorus of cheers from the crowd. Valenzuela threw 147 pitches en route to a complete game as the Dodgers beat the Yankees, 5-4. It was not vintage Valenzuela as he struggled mightily, almost being taken out more than once. But Lasorda stuck with him, and he finished the game. “It was my most difficult game ever,” Valenzuela said afterward.45

At the end of the season, Valenzuela received the Cy Young Award, edging out Cincinnati’s Tom Seaver, 70 points to 67 points, and becoming the youngest pitcher in history to be given the award.46 He was also named the National League Rookie of the Year, and he won the Silver Slugger Award as the best batter at his position. It was certainly the year of Fernando Valenzuela, and, more than anything, the mania that followed him that season was justified.

Valenzuela played nine more seasons with the Dodgers and made five more All-Star teams. He won 21 games in 1986. He played a total of 17 seasons for six teams and won 173 games. He completed 113 games and threw 31 shutouts. On June 29, 1990, he threw a no-hitter against the St. Louis Cardinals.

After retiring as a player, Valenzuela joined the Dodgers’ Spanish-language radio broadcast alongside Jaime Jarrín. In 2011 he was inducted into the Latino Baseball Hall of Fame and in 2013 the Caribbean Baseball Hall of Fame. In 2015 he became a US citizen, joining 8,000 others at the naturalization ceremony in Los Angeles.47 While he could have had a private ceremony, he opted instead to join others who had made a similar journey to their citizenship. In 2023 the Dodgers retired his number 34.48

Valenzuela’s statistics, as great as they are, would not be enough to enshrine him at Cooperstown, but the impact he has had on Mexican American culture would. He brought approximately 9,000 more fans to the games at which he pitched. He increased the Mexican American fan base of the Dodgers from around 10 percent when he started playing to 50 percent as of 2024.49 He was a tireless advocate for encouraging boys and girls to stay in school and visited countless elementary schools during his career to inspire the youth. He was appointed by President Barack Obama in 2015 as a presidential ambassador for citizenship and naturalization.

More than anything, Valenzuela helped bring the Mexican Americans who had been marginalized by perceived mistreatment and brutal removal from Chavez Ravine back to the ballpark. In the process, he gave them a feeling that they belonged there because one of their own was on the mound, and that somehow, he represented their dreams of what was possible. He fundamentally altered the composition of the Dodgers fan base by what he accomplished in his rookie season and continues to do as a former player and broadcaster today. He is beloved by those who saw him play and by new generations who listen to him broadcasting Dodgers games over the radio.

Valenzuela blazed the trail for future Dodgers greats like Hideo Nomo, as well as new Dodgers Shohei Ohtani and Yoshinobu Yamamoto. One could make a compelling case that Valenzuela belongs in the Hall of Fame not because of his impact statistically, but his impact culturally. For both Dodgers fans and Mexican Americans alike, Valenzuela will remain a baseball and cultural legend.

JASON SCHELLER is a professor of history at Vernon College in Wichita Falls, Texas. He is a graduate of Texas Tech University. His graduate work has been featured in the books “The Empire Strikes Out: How Baseball Sold U.S. Foreign Policy and Promoted the American Way Abroad,” by Robert Elias, and “The Boys Who Were Left Behind: The 1944 World Series Between the Hapless St. Louis Browns and the Legendary St. Louis Cardinals,” by John Heidenry and Brett Topel. He joined the Dallas-Fort Worth Banks-Bragan chapter of SABR in 2018.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, BaseballAlmanac.com, and the Fernando Valenzuela player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Thanks to Jorge Iber, Dodgers team historian Mark Langill, Rachel Wells, and Roger Lansing at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as well as Pat and Joy Scheller, Holly Scheller, and Greg Fowler for their support.

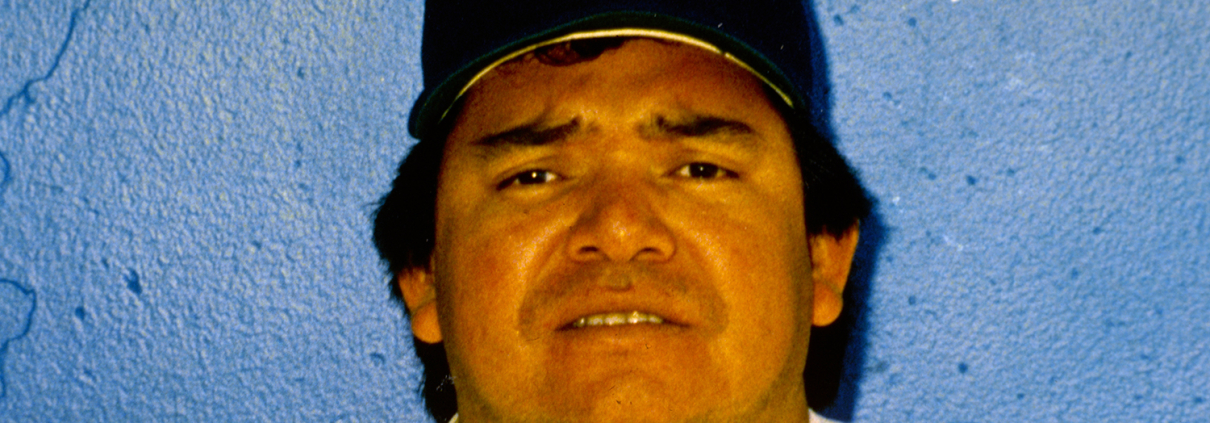

Photo credit: Fernando Valenzuela, SABR-Rucker Archive.

Notes

1 Dylan Hernandez, “Fernando Valenzuela Was a Game-Changer for the Dodgers, Baseball, and Los Angeles,” Los Angeles Times, March 30, 2011, https://www.latimes.com/sports/la-xpm-2011-mar-30-la-sp-0331-fernandomania-20110331-story.html, accessed November 14, 2023.

2 Hernandez.

3 Jason Turbow, They Bled Blue: Fernandomania, Strike Season Mayhem, and the Weirdest Championship Baseball Had Ever Seen: The 1981 Los Angeles Dodgers (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019), 76.

4 Erik Sherman, Daybreak at Chavez Ravine: Fernandomania and the Remaking of the Los Angeles Dodgers (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2023), 55.

5 Mike Davis, “Valenzuela Crafts 5-hitter, Blanks Astros in 1st Start,” San Bernardino County (California) Sun, April 10, 1981: 64.

6 Stew Thornley, “July 10, 1934: Carl Hubbell Strikes Out Five Hall of Famers in a Row at All-Star Game,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/july-10-1934-carl-hubbell-strikes-out-five-hall-of-famers-in-a-row-at-all-star-game/, accessed November 24, 2023.

7 Jerome Crowe, “A Screwball Chain of Events Led the Dodgers to Fernando Valenzuela,” Los Angeles Times, March 28, 2011: C-2

8 “Chubby Rookie Blanks Astros, 2-0,” Santa Cruz (California) Sentinel, April 10, 1981: 48.

9 Sherman, 56.

10 Turbow, 53.

11 Logan Hobson (United Press International), “Dodger Rookie Baffles Astros,” Ukiah (California) Daily Journal, April 10, 1981: 4.

12 Paul Oberjuerge, “Fernando Has Dodgers in Fat City,” San Bernardino County Sun, April 15, 1981: 21.

13 Sherman, 60.

14 “Dodgers Rookie Sensation Stumps Giants on Four-Hitter,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, April 15, 1981: 18.

15 “Ole! Fernando Does It Again, 2-0 Over S.D.,” San Bernardino County Sun, April 19, 1981: 19.

16 “Valenzuela’s Magic Dazzles Astros, 1-0,” New Braunfels (Texas) Herald-Zeitung, April 23, 1981: 7.

17 “Valenzuela Beats the Odds, Astros Again: He Pitches, Hits Dodgers Past Sutton, Astros, 1-0,” San Bernardino County Sun, April 23, 1981: 73.

18 “Valenzuela’s Magic Dazzles Astros, 1-0.”

19 Turbow, 78.

20 “Los Angeles’ Valenzuela Stills Giants,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, April 28, 1981: 11.

21 Sherman, 61.

22 Vic Wilson, “Fernandomania,” The National Pastime, 2011, https://sabr.org/journal/article/fernandomania/, accessed November 30, 2023.

23 Wilson.

24 Sherman, 90.

25 Jesse Sanchez, Nathalie Alonso, and David Venn, “Fernandomania Still Resonates Decades Later,” MLB.com, https://www.mlb.com/news/featured/remembering-fernandomania-40-years-later, accessed November 30, 2023.

26 Mike Tully, “Valenzuela Finally Scored Upon,” Ukiah Daily Journal, May 4, 1981: 6.

27 Turbow, 81.

28 Sherman, 85.

29 Joseph Durso, “The Buildup for Valenzuela Annoys Some of the Mets,” New York Times, May 9, 1981: 15.

30 Durso.

31 “Valenzuela Does It Again…,” Greenwood (South Carolina) Index-Journal, May 9, 1981: 9.

32 Turbow, 81.

33 “Valenzuela Does It Again….”

34 Richard Cuicchi, “June 6, 1945: Boo Ferriss Wins Record 8th Straight Game to Start Career,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/june-6-1945-boo-ferriss-wins-record-8th-straight-game-to-start-career/, accessed December 23, 2023.

35 Ed Rumill, “The Ferriss Wheel,” Baseball Digest, August 1945: 39-42.

36 Sherman, 89.

37 Mike Davis, “Fernando (8-0) Wins but Gives Up 1st HRs,” San Bernardino County Sun, May 15, 1981: 50.

38 “Phils End Valenzuela’s Winning Streak on Shutout,” Ukiah Daily Journal, May 19, 1981: 4.

39 Associated Press, “Loss wired to Georgia cops,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 20, 1981, Section 2: 9.

40 Turbow, 93.

41 “Valenzuela Equalled Rookie Shutout Mark,” Iola (Kansas) Register, September 19, 1981: 7.

42 “Valenzuela’s Four-Hitter Paces Dodgers Over Astros,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, October 11, 1981: 42.

43 David Leon Moore, “Dodgers, Monday Leave the Expos Feeling Blue, 2-1,” San Bernardino County Sun, October 20, 1981: 44.

44 “Recapping the Greatest World Series Rivalry,” San Bernardino County Sun, October 20, 1981: 44.

45 David Leon Moore, “Fernando Comes Back; Yanks Don’t: Dodgers Survive Slow Start for 5-4 Victory,” San Bernardino County Sun, October 24, 1981: 33.

46 Jack Lang, “Valenzuela Nips Seaver for ‘Cy,’” New York Daily News, November 12, 1981: 1.

47 Steve Dilbeck, “Dodgers’ Fernando Valenzuela Becomes a U.S. Citizen,” Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2015. latimes.com/sports/dodgers/dodgersnow/la-sp-dn-dodgers-fernando-valenzuela-us-citizen-20150722-story.html, accessed November 30, 2023.

48 “Dodgers to Retire Fernando Valenzuela’s No. 34 in August,” ESPN.com, https://www.espn.com/espn/print?id=35590016, accessed November 30, 2023.

49 Sherman, 240.