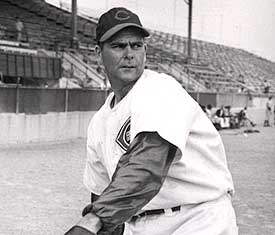

Ray Starr

The deep and talented farm system developed by General Manager Branch Rickey began to pay dividends when the St. Louis Cardinals won the National League pennant in 1930 and the following year won 101 games and captured the World Series. The team was expected to be even stronger in 1932 because the organization’s top three minor league pitchers, Dizzy Dean, Tex Carleton, and Ray Starr were expected to join the club. Carleton won 100 major league games; Dean became a Hall of Famer; but what about Starr?

The deep and talented farm system developed by General Manager Branch Rickey began to pay dividends when the St. Louis Cardinals won the National League pennant in 1930 and the following year won 101 games and captured the World Series. The team was expected to be even stronger in 1932 because the organization’s top three minor league pitchers, Dizzy Dean, Tex Carleton, and Ray Starr were expected to join the club. Carleton won 100 major league games; Dean became a Hall of Famer; but what about Starr?

He pitched in just three games for the Cardinals in 1932, then hung around baseball for the next dozen years, pitching for nine other major league organizations with “a list of clubs that would shame a train announcer.”1 At one point he even played semi-pro ball in North Dakota. It wasn’t until the manpower shortages during the World War II years that he finally got a chance to pitch regularly in the big leagues.2 Although he was in his mid-thirties by that time, he won 15 games in 1942 and made the National League All-Star team. Starr may have been correct when he said, “I think I could have been a winner up here since 1931 if they’d ever given me a chance.”3

Raymond Francis Starr was born on April 23, 1906, in Nowata, Oklahoma, a small town in the northeast corner of the state about 50 miles north of Tulsa. His parents were Charles, a native of Pennsylvania, and Almeta, from Ohio. Ray was the oldest of three boys. His brother Vernon was about a year and a half younger than him, and brother Paul about seven years younger. Like many men in the area, Ray’s father was employed in the oil industry, working as a foreman on a well site in 1910 and as a driller in 1920.

In 1922 the family moved to Centralia, Illinois, where the teenage Ray worked with his dad on the oil drilling rigs in the area. By 1925 he and his brother Vern got “baseball jobs” and he began pitching and Vern played shortstop for a local independent team sponsored by the Burlington Northern Railroad. 4 Ray was spotted by famous St. Louis Cardinals scout Charley Barrett and offered a tryout at Sportsman’s Park. Soon afterward he was signed to a contract and assigned to Danville, Illinois, in the Class B Three I (Illinois-Indiana-Iowa) League, one of the many minor league teams now in the Cardinals’ chain.

He pitched a perfect game against Bloomington in his fourth professional game, but was used mostly in relief the rest of the season and finished the year with a 3-5 record and a 6.60 ERA. The next season he dropped down to Class D with the Marshalltown Ansons in the Mississippi Valley League and won 11 games before being sold back to Danville late in July. Ray refused to report and was suspended by Marshalltown. He apparently changed his mind because one report said he returned to Danville late in the season and went 4-1 to help them win the league pennant, although this is not reflected in his minor league record. 5

Ray began the 1928 season with Danville again but finished the year in the Western Association with Topeka, Kansas. He returned to the same league the next year with Shawnee, Oklahoma, and finally reached the potential that had been predicted for him by winning 24 games with a 2.78 ERA. It may have been proximity to his boyhood home, but according to Ray his success was because he had finally gotten his mechanics straightened out after Danville manager Punch Knoll tried to change his pitching motion. On June 15 he beat Joplin, 8-2 in the first game of a twin bill and pitched thirteen innings in the nightcap.

It was then he first picked up the nickname “Iron Man” for his willingness and ability to pitch both ends of a doubleheader. Although no documentation could be found, several sources reported he had started and won both ends of a doubleheader twenty-one times during his career. Ray also claimed there were at last two dozen other occasions where he split the two games, but he insisted he never lost both games of any twin bill he pitched. These feats led to comparisons to another pitching Iron Man, Joe McGinnity.

Starr won 17 games in 1930 in his third stop in Danville. The next year the Cardinals promoted him to their AA farm team in Rochester, New York. He went 20-7 with an excellent 2.83 ERA and gave much of the credit to Billy Southworth, who Starr called the best manager he ever played for. His victory total was second in the International League to Yankee farmhand Johnny Allen. He performed his iron man stunt three times that season, winning five of the six games.

The Red Wings won the pennant and faced the St. Paul Saints, winners of the American Association, in the “Little World Series.” Ray was used in relief early in the series but got the start in the decisive game seven and beat St. Paul, 9-3, for the championship. He reportedly had a clause in his contract stipulating that if he won 15 games he would be promoted directly to the Cardinals the following season or they would risk losing him to another organization. St. Louis listened to offers from the Yankees ($50,000), Dodgers ($40,000), Cubs, Giants, and Pirates, but in November decided to purchase his contract from Rochester and bring him to spring training the following year.

In November 1931, St. Louis manager Gabby Street said, “I don’t know much about Ray Starr, who’s coming up from Rochester, but from all the dope I hear he’s going to be a first class prospect for our team next year.”6 One report even said “… the Cardinals may think as well of Ray Starr as they do of the more celebrated Dizzy Dean.”7 The Cardinals were so confident in their young pitchers that they traded 17-game winner Burleigh Grimes to the Cubs in the off-season.

Starr had a good spring and made the club but was expected to start the season working out of the bullpen. He had struggled with his control most of his career and needed to pitch regularly to remain sharp, so he asked the Cardinals to return him to Rochester where he could start every third or fourth day. Starr said, “It took me years to get control in pitching and I don’t want to lose that control now through lack of work.”8 The Cardinals agreed, and he spent most of the season back in the International League.

Instead of contending for another pennant, the Cardinals fell into the second division in 1932; they invited Starr to St. Louis for a trial in September. He pitched three innings in relief in his major league debut on September 11 against the Giants in New York. He was given a start four days later against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field and threw a two-hit shutout, outdueling Dazzy Vance, and won his first big league game, 3-0. He struggled through his next start, allowing nine hits and five earned runs in a 7-1 loss to the Pirates.

Immediately after the season, on October 10, the Cardinals traded him, along with catcher Gus Mancuso to the New York Giants for outfielder Ethan Allen, catcher Bob O’Farrell, and left-handed pitchers Bill Walker and Jim Mooney. After only two major leagues starts, Street had apparently already soured on him: “He was a hard pitcher to figure out. One game he would go great, and the next he’d be batted out early. I couldn’t depend on him. A pitching staff with five pitchers like him would keep a club in the second division all season.”9 Initially Starr was surprised, but later he welcomed the news, especially because Billy Southworth, his old Rochester manager, had been hired as a coach by the Giants.

Despite his high hopes he got into only six games and when the Giants traded Sam Leslie to Brooklyn for Lefty O’Doul and Watson Clark on June 13, they were one player over the 23-man roster limit. Starr was the odd man out; the next day he was sold to the Boston Braves. He pitched six innings and had a no-decision in his first start for Boston and made just eight relief appearances the rest of the season. It was only after the season ended that Starr revealed he had injured his back in a car accident the previous winter, and that limited his effectiveness all season. In November he filed suit in county district court against Michael Daily Service Company, owner of the truck that hit him, asking for $50,000 in damages. No resolution of this case could be found.

Starr went to spring training with the Braves in 1934 but in April was sold to Minneapolis of the American Association. He got off to a good start, winning five straight decisions, but in late July he left the team. Some reports indicated he was dissatisfied with his contract and had jumped the club, but team officials said the absence was allowed as Ray wanted to be with his wife who was expecting the couple’s second child. There may have been something to the salary dispute as it was said he weighed offers from a couple of fast semi-pro teams in Chicago while he was with his wife. After a couple of weeks, he rejoined the Millers. He had a record of 16-17 with an ERA over 5, but pitched in 260 innings, proving he was healthy again.

He began the 1935 season with Minneapolis again but when the club acquired Denny Galehouse from the Cleveland Indians in late May, Starr was the odd man out again, and was sold to Toronto of the International League, an affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds. He was never happy in Toronto, being at odds with manager Ike Boone about pitching regularly, and in late June there was some unnamed rules violation for which Starr was fined. After he refused to pay the fine, he was suspended and left the club. Declaring, “I’m all through with organized baseball,” Starr hooked on as player-manager with a semi-pro team in Jamestown, North Dakota, for the rest of the season. 10 He had one memorable matchup with Satchel Paige, who pitched for neighboring Bismarck, dropping a 1-0 decision.

Toronto never bothered to put Starr on their reserve list, so he essentially was a free agent. The next team to take a chance on him was the Syracuse Chiefs of the International League, an affiliate of the Boston Red Sox. Chiefs president Jack Corbett remembered Starr from his time in Rochester a few years earlier. After signing his contract Ray said, “I never felt better in my life and I’m confident I’ll be able to do at least 50 percent more work on the mound for Syracuse that most pitchers figure on doing. I’m sure I’ll be able to take my regular turn every fourth day and occasionally fill in between times, working a full doubleheader now and then. I figure on the greatest season of my life and on turning in a performance for the year as a whole that will put me back where I belong, in the ‘big league’”.11

At the time in the minor leagues, personnel decisions were often based on how much another team was willing to pay to purchase a player, rather than how well that player was performing. By this stage of his career, Starr was well aware of this fact. He performed another “Iron Man’ stunt on May 10, shutting out Toronto, 9-0 and 2-0, in a doubleheader, allowing just two hits in each game, but in early July he was sold to the Nashville Volunteers of the Southern Association. This would be Ray’s tenth minor league team and the sixth major league organization he worked for. He won nine games for Nashville the rest of the season, but when reporting for spring training the next year, he repeated his threat that he would be “through with baseball this season unless I have a great season.”12

Starr needed to put off retirement a little longer as he won 19 games for Nashville in 1937, and even collected a few votes for league MVP. The highlight was another doubleheader win over Little Rock on June 27. He took a step backwards the next season, going 14-20 with his ERA going up by more than one run a game. He started the 1939 season 1-4 with an ERA of seven before Nashville shipped him to the Fort Worth Cats of the Texas League. The change in scenery seemed to rejuvenate his rubber right arm once again; in his first appearance he threw 18 2/3 scoreless relief innings. Ripley’s “Believe It Or Not” made note of this achievement because he began pitching on May 31 and was still pitching in June, the game ending at 12:45 on June 1. He eventually ran his scoreless streak to 34 innings, tying a Texas League record set by Mort Cooper.

Given the opportunity to pitch regularly, Starr ended up winning 18 games with a 2.34 ERA. He may have pitched so well because he felt young around the other pitchers on the Cats staff. The team’s other top starters were 40-year-old Fred “Firpo” Marberry and 22-game-winner Ed “Beartracks” Greer, who was 38. The Cats finished fourth in the league but upset pennant-winning Houston in the first round of the playoffs and faced Dallas in the championship series. Starr used his curve ball to hold Dallas to six hits in a 6-0 shutout in game four to give Fort Worth a 3-1 series lead and the next day came in from the bullpen to stop a Dallas rally. Fort Worth won, 9-7, to take the series and earn the right to represent their league against the Southern Association champion in the Dixie Series.

As fate would have it, Nashville, who had given up on Starr that spring, was Fort Worth’s opponent in the series. Starr beat his former teammates, 10-2, in the opener, but was knocked out of game four in the sixth inning. Nashville won game five to take a 3-2 lead in the best-of-seven series. Marberry spun a one-hitter to win game six, 11-0, and Starr came back in game seven. He mixed in a good curve with his fastball to hold Nashville to two hits, shutting them out, 6-0. The victory gave the Cats the Dixie Series title, a win that must have been especially gratifying for Starr.

Ft. Worth fell into last place by the second half of the 1940 season, and Starr was sold to Dallas in late July. His combined record was 12-17 with a good 2.78 ERA. In December he returned to the Cincinnati Reds organization when he was sold outright to Indianapolis of the American Association. Starr was chosen to start in the league All-Star Game and had an excellent season in 1941, winning 20 games. He finished second in the American Association MVP voting to Louisville shortstop Johnny Pesky.

On August 30 his contract was purchased by the Reds and he returned to the major leagues after a seven-year absence. He lost his Reds debut, 1-0, to the Pirates in the second game of a doubleheader on September 5. Starr was used in relief a couple of times but pitched shutouts in his last two starts of the year. The Reds finished in third place and his teammates voted him a full share of their World Series cut.

Starr began the 1942 season in the Reds’ starting rotation and was the hottest pitcher in the National league over the first half of the year, winning 12 games against just three losses. When he was younger, Ray had a good fastball to go with a curve. As he aged he mixed in pitches that were described as “junk balls” or “nothing balls” with a slow curve, and his control improved. To explain the hot start Starr said, “I’m not as fast as I used to be. I used to be as fast as Grove. Now I change pace on them.”13

Originally, he was not chosen for the All-Star team, but when teammate Paul Derringer was injured, manager Bill McKechnie named Starr as his replacement. He did not play in the game. He cooled off a bit in the second half, but many of his loses were through no fault of his own. On July 14 he threw a three-hitter but lost to the Phillies, 2-1. In August he lost a ten-inning game to Boston by the same score and later that month he pitched ten scoreless innings against the Giants only to lose in the eleventh.

He finished the year strong, allowing the Braves just two hits in a 0-0 tie on September 10. In his next start, Starr threw a five-hitter and beat the Brooklyn Dodgers, 4-1, knocking them out of the pennant race. In his final start, on September 20, he allowed just one run and seven hits in 12 innings against Pittsburgh but had a no decision. Starr’s 2.67 ERA was seventh in the National League and his 15 wins were eighth. He received nine points in voting for the award won by the Cardinals’ Mort Cooper.

Starr had another strong season in 1943. In his first start he beat the Cardinals, 1-0, in ten innings, allowing just five hits. On June 1 he beat the Giants, 3-1, on a five-hitter and a couple of weeks later threw a fourteen-inning shutout of the Pirates. In the second game of a July 8 doubleheader against the Phillies at Shibe Park, he pitched ten scoreless innings and surrendered only three hits. He was lifted for a pinch-hitter and had a no decision in the game, won by Philadelphia, 1-0, in fourteen innings. Overall, he pitched 217 1/3 innings in 36 games, 33 of them starts. He had a 11-10 record with a 3.64 ERA.

Starr always maintained he needed regular work to be effective, even insisting he could pitch every other day; and that one day of rest between starts was plenty. Often referred to as “Rubber-Armed Starr,” if he went too long between appearances, he would often volunteer to pitch batting practice. He explained, “If I lay off my arm gets too much strength in it. The ball feels as light as a pea and I can’t do nuthin’ with it. I want it to feel heavy.”14

Starr held out many springs, but the club that held his rights usually predicted he would sign “when the mood strikes him.” He always kept in good shape over the winter and didn’t need much spring practice. He had an unusual training method in that he would throw as hard as he could the first day of camp and then slowly work the soreness out of his arm. He claimed never to have had a sore arm during the season.

Before spring training in 1944, Starr said that unless McKechnie allowed him to pitch every other day, he didn’t want to pitch for the Reds any longer. He held out and later asked to be sold or traded. After a conversation with team president Warren Giles, he reconsidered and, although he was described as a “discontented employee,” reported to camp.

It was then discovered that he had a bone chip in his elbow and was unable to pitch. On May 26 the Reds sent him to the Pittsburgh Pirates, his fifth National League team, for the $7,500 waiver price. He pitched in 27 games for the Pirates, winning six, including two victories over his former Cincinnati teammates. In his second start for the Pirates he beat the Reds, 3-2, and a week later tossed a complete game seven-hitter, wining, 2-1.

In March of 1945 the Pirates announced that Starr was penciled in as a relief pitcher or spot starter, so he held out again. He got into only four games, losing two of them. In June he was given permission to leave the team to visit his son, who had taken ill, but when he did not return at the agreed upon time, he was suspended. Shortly thereafter he was sold to the Cubs (leaving the Phillies the only National League organization he never played for). He got into just nine games for Chicago, ringing up a 7.43 ERA in 13 1/3 innings. He was left off the Cubs’ World Series roster, but was voted a half share. The following spring Chicago released him to Oakland of the Pacific Coast League. Having now turned 40 years old, he finally retired from baseball and returned to his farm just outside Centralia.

Starr was the most famous resident of his small home town. The local paper, the Centralia Evening Sentinel, provided detailed coverage of his life, both on and off the field. On one occasion an ad in the classified section announced, “For Sale or Trade 4 Holstein cows, fresh, 400 chickens, 30 pigs, at Ray Starr place on highway north of Centralia.” When he and his family had left for spring training before the 1935 season, the Sentinel ran the following ad: “For rent, from Mar 6 to Sep 10th, 6 room furnished strictly modern house, with 10 acres of land. See Ray Starr, 3 miles north of Centralia.”15

When he was just beginning his long career in baseball, Ray had married Doris McBride on November 25, 1925. The couple had two children. Son Billy was born in 1929 and daughter Barbara Ann was born in 1934. Starr raised chickens and hogs on his farm and always kept a number of coon and bird dogs he used for hunting. He moved to a new place a little farther north up Route 51, which was closer to the town of Sandoval than Centralia, and opened a roadside restaurant/tavern called “Ray Starr’s Home Plate” along the highway. He died of an apparent heart attack on February 9, 1963, at the age of 56. Starr was survived by his wife and two children. He was buried in the town cemetery in Carlyle, Illinois.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Warren Corbett.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, all genealogical and family information was taken from Ancestry.com and statistics were taken from Baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, May 25, 1944

2 Because he was the father of two children, Starr had a 3-A draft classification and was exempt from military service.

3 Brownsville (Texas) Herald, June 29, 1942

4 Vern also caught Ray on occasion and later converted to a catcher full-time. He played two years of minor league ball with Bay City, Michigan, and Ottumwa, Iowa

5 Centralia (Illinois) Evening Sentinel, September 8, 1927

6 Centralia Evening Sentinel, November 28, 1931

7 Centralia Evening Sentinel, January 26, 1932

8 Albert Lea (Minnesota) Evening Tribune, April 18, 1932

9 Centralia Evening Sentinel, October 11, 1932

10 Moorhead (Minnesota) Daily News, July 2, 1935

11 Syracuse Herald, March 5, 1936

12 Kingsport (Tennessee) Times, March 5, 1937

13 Brownsville Herald, June 29, 1942

14 Centralia Evening Sentinel, July 19, 1942

15 Centralia Evening Sentinel, March 3, 1935

Full Name

Raymond Francis Starr

Born

April 23, 1906 at Nowata, OK (USA)

Died

February 9, 1963 at Baylis, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.