Joe Taylor

“[Joe] Taylor has such a vile reputation that I guess I couldn’t have the remotest interest in him, but he impressed me very much as a player.” – Branch Rickey1

“[Joe] Taylor has such a vile reputation that I guess I couldn’t have the remotest interest in him, but he impressed me very much as a player.” – Branch Rickey1

“When Taylor is ‘right’ he is definitely a Major League hitter. He has great reflexes, terrific wrist action and tremendously quick hands. He has as much power as almost any hitter in the game and an easy, near perfect swing.” – Lefty O’Doul2

“Joe Taylor should have been a superstar in the big leagues.” – Maury Wills3

All the superlatives that were directed toward Joe Taylor were always accompanied by a cautionary tone. After all, as baseball historian Dan Raley writes, “he was ox strong, overly developed in the upper torso, and he had a short compact swing that made him explosive at the plate.”4 He also had a suitcase full of demons, the biggest of which was his alcoholism.

Joe Cephus Taylor was born on March 2, 1926, in Chapman, Alabama, the only child of John and Mary (née Johnson) Taylor. His father worked in lumber mills and the building trades. At some point in the 1930s, his family migrated north to Pittsburgh.5 There he attended Connelley Vocational Trade School, opened in 1930 on Bedford Avenue in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. It is not known whether Joe completed his course of study there; records at the National Hall of Fame Library indicate that his highest level of education was grade school.

Joe entered the Army for a two-year stint from 1944 to 1945. After leaving the Army, his baseball experience was limited to playing softball. Gradually, he began playing sandlot ball as a catcher, where he caught the attention of Pittsburgh Courier sportswriter Earl Johnson. “Earl used to follow me in all our games. He wrote a lot of articles about me and was always encouraging me to make a career out of baseball. I would have stopped playing all together if Earl hadn’t kept urging me to stay with it.”6 Joe was not self-driven to play baseball but once his talents were pointed out to him, it became apparent to him that he could make money playing the game.

The Courier was integral in pounding the pavement for the inclusion of players of color in the big leagues. Over the years, Pittsburgh was the home of the iconic Negro League Crawfords and Homestead Grays.

Joe was coming up during the time that Jackie Robinson was breaking organized baseball’s color barrier. A blessing and a curse, the inclusion of blacks was certainly a major accomplishment, but at the same time it would be a death knell to the Negro Leagues.

It was at this time that Joe married Willa Mae Horsley on July 19, 1947. They went on to have two sons, Alan and Joe. Their home in Pittsburgh was at 705 Watt Lane. Outside of baseball, Joe worked as a window washer and a cab driver.7

Joe was a 6-foot-1, 185-pound right-handed outfielder nicknamed “Tommy Gun.” His first professional baseball assignment was for the Chicago American Giants of the Negro American League in 1949. While little is known statistically about the players, we do know that the Giants were awarded first place in the Western Division with a record of 48-35.8 With the Negro American League struggling to survive while their better players were defecting to Organized Baseball, Joe moved on in 1950 to the Winnipeg Buffaloes, an independent black team playing in the Manitoba-Dakota League. His teammates included Lyman Bostock Sr., as well as Hall of Famers Willie Wells and Leon Day. Again, statistics are limited. But as an example of his play, he drove in two runs on June 14, 1950, as Winnipeg defeated the Brandon Grays, 8-1, to win the Grays’ $1,400 Invitational Tournament.9

As the 1951 season began, Joe returned to the Chicago American Giants before moving on to the Farnham Pirates of the Class C Provincial League. The Pirates that year crafted a record of 52-71. The team was nearly all black and managed by Sam Bankhead. Some notable players of color included Humberto Robinson, Bob Trice and Josh Gibson Jr. Joe hit ten home runs and batted .360 during his stay at Farnham.

Joe’s maturation as a ballplayer accelerated in 1952 while he was playing with the St. Hyacinthe A’s of the Provincial League, a farm team of the Philadelphia Athletics. His teammates included Hector Lopez and Trice. Joe hit 25 home runs and batted .308 while leading the Provincial League in doubles with 35. For this, he was named to the All-Star team while helping St. Hyacinthe to a 79-49 record and a first-place finish. In September 1952, Philadelphia selected Taylor (and Lopez and Trice) to report to spring training the next season.10

In 1953 the Athletics moved Joe to the Williamsport A’s of the Class A Eastern League and then to the Ottawa A’s of the AAA International League. At Williamsport, he clouted ten home runs and batted .324. At Ottawa, his stats were comparable: seven home runs, 45 RBIs and a .315 batting average. His combined OPS was a very respectable .871. The Ottawa team included 17 future and former major league ballplayers. Both teams had losing records. At this time Joe expanded his resume to include winter ball, playing for Leones del Caracas 1953-1955, then for Johnny Temple in Venezuela in 1957. Pitcher Dick Fitzgerald, a winter ball teammate for one season, said he rarely saw Joe sober.11

Ottawa’s fortunes did not change in 1954, as they went 58-96. But Joe’s did. He emerged as a premier slugger in the International League, banging out 23 home runs with 79 RBIs while batting at a .323 clip with a hefty .940 OPS. This earned him his first trip to the big leagues with the last-place Philadelphia Athletics. Wearing number 20, Joe appeared in his first MLB game on August 26. He became the third African American player to appear for the Athletics, following Trice and Vic Power. In the second game of a doubleheader against the Boston Red Sox at Shibe Park on September 5, Joe led off the bottom of the seventh with the A’s trailing, 7-0, and hit his first MLB home run off Russ Kemmerer.

Despite such highlights, he hit only .224 (.578 OPS) in 18 games with the Athletics. To gain more seasoning, he began the 1955 season with the Columbus Jets of the International League. Soon thereafter, the Pacific Coast League’s Portland Beavers obtained him on option from Columbus. On May 15, he made one of the most spectacular debuts in Portland history, hitting three home runs in his first four plate appearances.

Arriving in Portland before sunrise with no baggage, he was put in the lineup at once for the Sunday twin bill against the Oakland Oaks. He slammed Karl Drews’s first pitch into the center field seats. In the fourth inning, he belted another Drews offering into the left field bleachers with one man aboard. Two innings later, Joe belted a Dick Strahs offering into the center field stands, giving the Beavers a 5-4 victory.12

That display was everything that one hoped Joe Taylor would be. He continued to play for the Beavers until he found the straw that broke manager Clay Hopper’s back. In a game when Joe was not in the lineup, he was sleeping off a hangover in the Beavers bullpen. Teammate Eddie Basinski hit a hard liner that sent the pitchers in the bullpen scrambling. Startled by the sudden activity, Joe instinctively grabbed the baseball. Basinski was called out on interference. Hopper, who was not enamored with Joe to begin with, was enraged and told him to get into the clubhouse where he couldn’t do the team any harm. This incident was the end of the road for Taylor in Portland.13 He had hit ten homers, drove in 55 runs, and hit .295 (.852 OPS).

The Beavers returned Joe to the Athletics, who promptly sent him to the International League’s Toronto Maple Leafs.

Taylor was purchased by the Seattle Rainiers from the Kansas City Athletics prior to the start of the 1956 season. With Joe, the Rainiers were a very good team, finishing second behind the Los Angeles Angels (led by PCL legend Steve Bilko). Joe crushed 24 homers with 89 RBIs while hitting .260 (.830 OPS). For his accomplishments, Joe was named to the All Pacific Coast League team.

In 1957, Joe returned to Seattle. This time he was under the guidance of baseball legend Lefty O’Doul. It was becoming apparent that Taylor’s home runs had two distinguishing characteristics. Almost all of them were of awesome proportions, and they came in clusters. It was equally apparent that Joe’s daily sobriety was questionable, yet he continued to hit at an all-star clip. His 1957 PCL season, a partial one at that, included 22 home runs, 72 RBIs, a .305 BA, and a .939 OPS. One of his teammates that year was speedster Maury Wills.

Sportswriter Len Anderson indicated the streakiness of Joe’s hitting in June 1957: “When the 31- year-old slugger is hot, he can belt the ball with ease out of any ballpark in the league. In fact, the great majority of his four-base wallops have been hit in the league’s larger parks – Sicks’ Seattle Stadium, Hollywood’s Gilmore Field and Seals Stadium in San Francisco. His lack of success, this year and last, in the league’s two home run parks, Wrigley Field in Los Angeles and Portland’s Multnomah Stadium, has been conspicuous, possibly because the inviting barriers in those arenas cause him to start over-swinging.”14

Anderson also noted that half of Taylor’s first 14 homers came in an 11-game stretch, and the other half over 53 other games. The 11-game stretch began in Seattle’s home opening doubleheader on April 30, when Taylor slammed three homers and drove in nine runs. Then, in mid-May, he hit five homers in six games. Finally, on May 26, he contributed two home runs and a 400-foot double off the fence.15

On August 2, the Cincinnati Redlegs purchased Joe from Seattle. Sportswriter Lou Smith reported that Cincinnati sent the Rainiers “a bundle of greenbacks and a player [Bob Thurman] to be optioned” in the deal.16 Smith referred to Taylor as “a 29 year old” even though he was 31 when the deal was announced. Dewey Soriano, Seattle’s general manager, said Taylor was the best hitter in the Pacific Coast League. “He can hit the ball as far as anyone and has good speed for a big man.”17 Joe stayed with the Reds for the remainder of the season. On September 10, Joe’s two-run shot in the bottom of the sixth off Johnny Antonelli to deep left field scored Johnny Temple, putting the Reds up, 2-1. They went on to win, 4-1. It was Joe’s first MLB home run in a winning effort.

September 16 was Joe’s greatest game of his MLB career, He accounted for all three Cincinnati runs in a 3-2, 10-inning victory over the Brooklyn Dodgers at Crosley Field, connecting for a first inning solo homer to right field off Johnny Podres, then again off Podres in the sixth. With the bases loaded and one out in the bottom of the tenth, he drew a walk to score pinch runner Bobby Henrich with the winning run.18 Despite the victory, the Redlegs were mathematically eliminated from the pennant that night.

On December 5, 1957, Joe was traded by Cincinnati with Curt Flood to St. Louis for Marty Kutyna, Willard Schmidt and Ted Wieand.

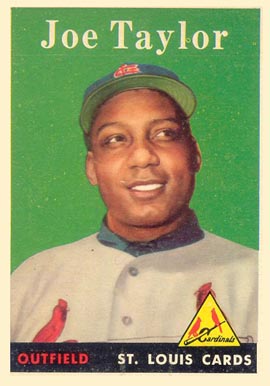

Joe split his playing time at the beginning of the 1958 season between the AAA American Association Omaha Cardinals and the St. Louis Cardinals. St. Louis was managed by Fred Hutchinson who, as a PCL legend himself, must have been very familiar with both Taylor’s strengths and his weaknesses. Joe clouted 10 home runs with 34 RBIs at Omaha while batting .270 (.899 OPS). In his limited play in St. Louis, Joe batted .304 with one home run and three RBIs. His OPS was a very respectable .911. Yet by the end of July, the Cards had seen enough of Joe and he was let go to the Baltimore Orioles for the waiver price of $20,000.

When Paul Richards was asked why he picked up Joe, he responded: “Because we needed a right-handed hitter with some power, more than a lefty, and Taylor fits that description. As a matter of fact, I tried to get him some time ago when Bob Nieman was sidelined but we couldn’t work it out then. We’ve got the spot now for second place and Taylor could help plenty, either as a pinch-hitter against left-hand pitching or alternating in the outfield. Since June 1, he has hit .304 with the Cards and last year hit .305 with Seattle. He can swing that bat.”19

Joe’s performance in Baltimore was somewhat lackluster. In 84 at-bats, he hit just two home runs and drove in nine runs. His .273 BA and .736 OPS were less than expected. The highlight of his 1958 Baltimore season came on August 9 when he went 2-for-5 with a solo home run off Tex Clevenger to help propel the Orioles to a 12-5 victory over the Washington Senators at Griffith Stadium.

As the 1959 season began, the Orioles remained confident in Joe’s ability. However, by July 27, exactly one year after he was acquired, Joe had just one home run and two RBIs. He was hitting a horrific .156 with a .653 OPS. Then his alcoholism once again reared its ugly head. Pleading that he overslept after arriving late for the Orioles-White Sox doubleheader, Joe was sold outright to Vancouver of the PCL. “He will make his next appearance for Vancouver,” declared a bristling Paul Richards, emphasizing Taylor’s sale to the Orioles affiliate in the Pacific Coast League was “outright.”20

With the 1959 Vancouver Mounties, Joe once again had his batting stroke back. He clubbed 23 home runs with 77 RBIs while crafting a batting average of .292 with a very respectable .920 OPS. Manager Charlie Metro could not get too angry with Joe and his shenanigans no matter how bad his behavior got. In fact, Metro humorously relayed the story of how Joe showed up at the San Diego Airport after missing the team plane and asked the gate attendant when the next train was leaving.21 Charlie could either bang his head against the wall or look the other way and keep Taylor’s bat in the lineup. Apparently, he chose the latter. Joe was named to the PCL All-Star team that year.

Joe played the entire 1960 season for the Seattle Rainiers, and it defined him as a Pacific Coast League legend both on the field and off. The Rainiers were an average team at best, finishing in a fourth-place tie under the tutelage of Dick Sisler. Joe finished the year with 30 home runs, 94 RBIs, a .291 BA, and a .907 OPS. The team was built around Joe.

It didn’t take Joe long to get started. He hit a home run over the dead center field wall of Sicks Stadium on opening day in a doubleheader against the San Francisco Seals, and would hit two more home runs that day. It was very similar to his debut with Portland in 1955. The home run to dead center, estimated to have traveled 500 feet, was the longest ball ever hit at Sicks Stadium.22

Yet, typical of Taylor, his success was always followed by some type of trouble. A month into the 1960 season, he went on a bender in Rainier Valley after a game. Coming out of a tavern, he climbed into someone else’s car. It looked like his – same make, model and color – but it wasn’t. As auto production was fairly standardized back then, his key fit into the ignition, the engine turned over, and he was off on a perilous ride. Before his outing was over, Taylor rammed this “borrowed vehicle” into another and was arrested for drunken and negligent driving, though luckily escaping auto theft charges. The Rainiers briefly suspended him but gave him a second chance.23

Joe’s career reached its peak in 1960. His reputation was well known in the majors, however, so there was no real chance of progressing beyond the PCL. He had a nice season for the San Diego Padres during 1961, banging out 26 home runs with 74 RBIs, a .268 BA, and an .876 OPS.

In 1962 Joe played his final season in the PCL split between the Hawaii Islanders and the Vancouver Mounties. By 1963, Joe could only find employment in the Mexican League, playing for both the Pueblo Pericos and the Mexico City Tigers.

In summary, his career was defined by great promise, but even more so by tragedy, as alcoholism reduced Taylor’s baseball life to a shadow of what it might have been.

After his playing days ended, Taylor returned to Pittsburgh. According to Dan Raley, there was talk that the former ballplayer became an ambulance driver, but that “seemed a bit ironic considering his shaky record behind the wheel.” Rather, “he spent much of his free time seated on a bar stool at his favorite hangout.”24

Raley also observed that “taking into account the alcohol abuse he heaped on himself, the former Rainiers slugger lived far longer than anyone might have imagined.”25 Joe Taylor died on March 18, 1993, in a Veteran’s Administration hospital in Pittsburgh.26 He was survived by his wife, Willa Mae, two sons, Alan and Joe, and five grandchildren.27He was laid to rest in Greenwood Cemetery in Pittsburgh.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Phil Williams, Rory Costello, and Norman Macht, and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 Branch Rickey, Branch Rickey’s Little Blue Book; Wit and Strategy from Baseball’s Last Wise Man (Branch Rickey & John J. Monteleone, June 1995): 110.

2 Len Anderson, “Feast-or-Famine Taylor of Seattle Having Best Year, The Sporting News, June 19, 1957: 29.

3 Dan Raley, Pitchers of Beer: The Story of the Seattle Rainiers (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011): 246.

5 Per census records, draft registration, marriage license, and other materials from Ancestry.com.

6 Len Anderson, “Feast-or-Famine”

7 National Baseball Hall of Fame folder.

8 cnlbr.org The Chicago American Giants were awarded the Western Division title when the Kansas City Monarchs were unable to defend their crown because several of the players were signed by Major League Baseball.

9 “1950 Tournaments,” Western Canada Baseball website (http://www.attheplate.com/wcbl/1950_1k.html)

10 “Local Players to A’s,” Montreal Gazette, September 16, 1952.

12 L.H. Gregory, “Joe Taylor Hits Three HRs in PCL Bow with Portland,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1955: 28.

13 Ed Mickelson, Out of the Park: Memoir of a Minor League Baseball All-Star (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015): 154-155.

14 Anderson, “Feast-or-Famine.”

15 Anderson, “Feast-or-Famine.”

16 Lou Smith, “Lou Smith’s Notes,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 2, 1957: 21.

18 Game Logs, Baseball Reference

19 Hugh Trader, untitled article from July 27, 1958, within Taylor’s National Baseball Hall of Fame folder.

20 “Good Sleep Sends Ballplayer Down,” AP article from July 27, 1959 within Taylor’s National Baseball Hall of Fame folder.

26 Tom Hawthorn, “The Mounties of a Baseball Era Gone By,” The Globe and Mail (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), July 5, 2006.

Full Name

Joe Cephus Taylor

Born

March 2, 1926 at Chapman, AL (USA)

Died

March 18, 1993 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.