Harry Staley

In the box, Beaneater Harry Staley pitched a mystifying curve, yet he often wrestled with his control and the barrage of temptations offered baseball stars. At his peak, the curves, the speed, and workhorse stamina helped the Boston Beaneaters to three straight pennants (1891-1893). “Staley wild” was an often-used phrase by the papers of the day while reports of reprimands and his frequent pitiful physical condition attested to his rowdiness and poor habits. Undeterred by his personal struggles and the numerous pitching rule changes during the 1890s, Staley won 72 games in his four years with the Beaneaters.

In the box, Beaneater Harry Staley pitched a mystifying curve, yet he often wrestled with his control and the barrage of temptations offered baseball stars. At his peak, the curves, the speed, and workhorse stamina helped the Boston Beaneaters to three straight pennants (1891-1893). “Staley wild” was an often-used phrase by the papers of the day while reports of reprimands and his frequent pitiful physical condition attested to his rowdiness and poor habits. Undeterred by his personal struggles and the numerous pitching rule changes during the 1890s, Staley won 72 games in his four years with the Beaneaters.

Henry Eli Staley was born on November 2, 1866, in Jacksonville, Illinois, to William and Emily Staley.1 The Maryland natives were married in 1860. Emily gave birth to three daughters before Harry, then one more daughter, and two more sons by 1879. Harry grew up in Springfield, Illinois, and his family maintained a home there for the rest of his life. Staley’s mother died in 1910, several months after Harry’s untimely demise, while his coal-mining father survived to 1931.2

Staley began his baseball career with various amateur teams including the one from his hometown; his professional career began with the St. Louis Whites of the Western Association. The Whites acted much like the later farm teams with talent moving back and forth to Chris Von der Ahe’s National League team, the St. Louis Browns. (Von der Ahe also owned the Whites.) According to The Sporting News, Staley “had no superior as a pitcher in the Western Association.”3

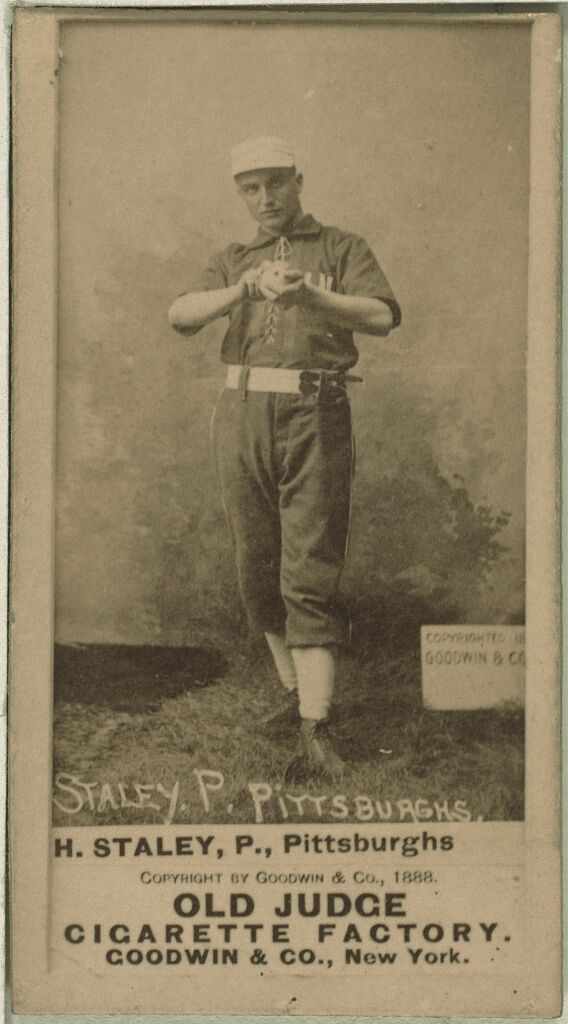

A baseball-card portrait of Staley from his time with the Whites sits in the National Archives. The right-handed pitcher appears shorter than his stated 5-feet-10. His weight was listed as 175 pounds. His physique shows the athleticism of youth, though his trimness would disappear with age and bad habits. From illustrations in newspapers, his eyes are soft and dignified, but in the photo portrait the darkness and menacing intensity in his eyes is striking.

Von der Ahe’s Western Association team was not financially sustainable, so he sold the club in June of 1888 along with most of its players to Indianapolis interests.4 Staley and first baseman Jake Beckley, though, were sold to the Pittsburg Alleghenys for $4,500.5 By June of 1888 Staley was pitching in Pittsburg alongside pitching stars James “Pud” Galvin and Ed Morris as well as the future evangelist Billy Sunday.

Staley’s first recorded game with the Alleghenys came on June 23, 1888, an away game against the Chicago White Stockings. Staley closed, gave up three runs, and threw two wild pitches. The game was out of hand long before Staley stepped in the box and the team lost 12-1. His rough start would soon be forgotten. On June 30 before his new hometown crowd, Staley struck out four and limited the White Stockings to two earned runs in a 6-4 win.6 The Sporting News credited Staley’s pitching for the win, confirming its earlier prediction of excellence in Staley if he ever had “a club backing him up.”7 On July 10 Staley struck out eight Philadelphia batters; however, the Pittsburg bats were unable to hold up their end, leading to a 1-0 loss.8 A week later, the rookie pitcher recorded his first shutout, against the Boston Beaneaters. He gave up no earned runs, walked only one, and hit one batter in the 4-0 victory.9 For the rest of July, Staley maintained a steady stream of strikeouts and solid pitching performances.

Staley’s trouble with control first appeared in August of 1888. In two games his wild pitches and walks led to defeats in close games against league leaders New York and Chicago.10 Staley regained some control at the end of August, striking out five in a 9-2 victory against Chicago; however, at the end of the season he was “hit freely” by Washington and was described by the Boston Globe as “very wild.”11 Despite his late-season trouble, the Alleghenys pitching rotation of Ed Morris, Staley, and Galvin was described as “steady, reliable and effective.”12 Staley ended the season with a 2.69 ERA, two shutouts, and a 12-12 record, and was reserved by the Alleghenys for the 1889 season.13

The Pittsburg Dispatch thought highly of Staley’s work in the box and declared that he would be a “first-class man” one day.14 Yet rumors circled around the city of Staley’s impending trade to Louisville. The Alleghenys manager, Horace Phillips, cited his “high opinion of Staley,” and team owner William Nimick declared that he “wouldn’t take thousands of dollars for Staley.”15 The stories continued as did negotiations behind the scenes into February, with the owner of the Louisville Colonels of the American Association stating that “Staley would make the Louisville club a valuable pitcher.”16 The Pittsburg Dispatch relayed the reasons for Staley’s late-season struggles, according to manager Phillips: Staley had been “led astray” by his teammates, “led into bad company,” and was not taking care of himself. Phillips heatedly protested the story, calling it and his statements wholly “fabricated.”17

By the middle of February 1889, the trade rumors were gone. The team decided it needed Staley more than a good third baseman.18 The reports on Staley’s condition were promising. He apparently spent most of the winter with his family in Illinois and then traveled to Hot Springs, Arkansas, to ensure that he was healthy and in playing condition by spring. As the young pitcher improved his arm and defensive skills, the team worked to ensure that he and his other errant teammates stayed in playing condition. In March the Alleghenys dictated a set of behavioral standards for players to encourage them “to do right, morally and otherwise.”19 The concern for player morality and its effect on the game was shared by most teams of the day. The press was not optimistic for success.

Preseason matches showed Staley had improved in speed and defense, but walks and wild pitches still evidenced “a wildness” that observers feared would “prove costly.”20 The Alleghenys went 8-8 in their first four series. In a May 8 game against the White Stockings, Staley pitched well, yet his defensive abilities contributed more to the team’s win. Staley stopped a hard-hit line drive in the ninth to protect Pittsburgh’s 3-2 lead. The skillful stop left Staley’s left hand battered and barely able to grip the ball. He finished the game by relying on the defensive work of his team. He pitched through May with a bruised hand. His usual skill was absent and he gave up more hits and scores than usual. Pittsburg’s bats were productive, but could not keep up.21

As May turned to June, the Alleghenys slid further down the standings. Injuries had left Staley as the only experienced pitcher on the team, forcing him to work the box more often than usual. On May 31 owner Nimick awarded his team’s workhorse a new suit of clothes in honor of his effort rather than any real success.22 The team was 12-18. In a sentiment familiar to most team owners, Nimick asked for “patience and public encouragement.”23

On June 29 Staley pitched a shutout against Philadelphia in front of the home crowd. The visitors “couldn’t touch Staley,” and the Alleghenys won 8-0. The second half of the season was no better for Pittsburgh, the team going 9-16 in July, but Staley’s control and speed returned.24 Staley’s improvement also helped him work his way out of a fine imposed on him by the team in June for an unknown infraction during a road trip. Energized by his rediscovered command in the box, the players actively lobbied to have the fine returned.25

Staley continued to be in “excellent form” through the end of the season, while the Alleghenys put together several winning streaks in August and September, However, this burst of productivity could not remedy the record earned from May to July. Pittsburg ended up in fifth place, 25 games behind the first-place New York Giants. Staley won 21 games and lost 26 with a 3.51 ERA.

Staley was placed on reserve for the 1890 season; however, the rumblings between players and owners during 1889 were about to change his status. The Players’ League grew out of the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players, established in 1885 to represent athletes and resolve conflicts with baseball ownership. The National League’s abuses of the reserve clause and attempts to limit salaries as well as the absence of a system of redress for players increased tension with the owners.26 Staley was an “enthusiastic supporter” of the Players’ League, whose preparations to break away began during the summer of 1889.27 Like many, he waited until December to officially sign with a Brotherhood team so as not to risk losing his last month’s pay to the fury of his old bosses.28 Staley signed with the Pittsburgh Burghers as did most of his Alleghenys teammates, including “Pud” Galvin, Ed Morris, and Jake Beckley.

Staley was back in Hot Springs by January of 1890 with teammate Billy “Yank” Robinson. The pair undoubtedly took advantage of the spring-supplied “hydrotherapy” popular at the time to improve their condition and drop Staley’s weight. Staley also worked on quickening his delivery, a specific assignment from his new manager, Ned Hanlon.29

By March, Staley was back in Pittsburgh and down to his playing weight. He was “enthusiastic about the Brotherhood’s chances for success,” but the Burghers posted a disastrous season and the Players’ League succumbed to economic pressures and the machinations of the National League.30 Staley managed 21 wins and a slightly better ERA, but he lost 25 and continued to show a game-losing wildness. In a July 8 game at Philadelphia, Staley gave up nine earned runs, and a week later he gave up seven against New York.31 On July 26 He held Boston to just three hits until the end of the eighth with Boston leading 2-0. Pittsburg scored three in the ninth, but Staley lost control in the bottom of the ninth and gave up two walks. The next batter hit a triple, scoring the runners and winning the game.32 Staley received little support from his fielders, and batters had little trouble putting his pitches in play.

In August Staley’s off-the-field carousing became public again. Seven members of the team were accused of drinking and violating team rules. Ed Morris was released from the team, his winning record unable to save him. Staley’s infraction was his second offense and he received a heavy fine.33 The fine and public reprimand apparently had good effect. Staley’s strikeouts increased as his walks decreased. The Boston Globe reported him “in good trim” as he held the Beaneaters to just one hit per inning over six.34 He hit two home runs in August, and despite his earlier struggles, the Pittsburg Dispatch proclaimed Staley “one of the best pitchers in the country today.”35 The Pittsburg Burghers finished 60-68 in sixth place. Rumors of players grumbling about manager Hanlon filled the Pittsburg Dispatch, and Staley was reported to be “tired of the Players’ League.”36 In turn, the Brotherhood was not pleased with his off-field activities and told the pitcher he “must choose better companions if he wanted to stay with” the Burghers.37

The Burghers owner and his Players’ League peers across the country began to merge with their National League counterparts across town in an attempt to save what remained of their investments.38 In January of 1891, the Players’ League wrapped up its last business, Staley was back in Hot Springs, and he signed with the new Pittsburg Pirates.39 The team headed to St. Augustine, Florida, in April, but Staley showed up “a little heavy.”40 The 24-year-old pitcher struggled with his weight for the remainder of his career. Neither his pitching form nor waistline had improved by an April 23 game against Chicago, a 9-2 loss. A few days later, Staley and the Pittsburg offense gave the hometown crowd quite a show with a 17-6 victory over the Cleveland Spiders. Staley struck out eight, gave up no walks, and allowed only three earned runs. The Pirates, though, were headed to a last-place finish in 1891 and had “too many twirlers on their salary.”41 Aside from the Cleveland game, Staley’s performances were lackluster. Pittsburg no longer wanted him, but interest remained in the rest of the league.

Brooklyn wanted Staley, and sportswriters reported the trade as a done deal.42 Staley, however, said no. Unable to come to terms with the pitcher, the Pittsburg Pirates released him, and the Beaneaters swooped in and signed him. The acquisition was met with much fanfare in the Boston papers. They hailed him “an artist,” “a handsome young athlete,” and “the best pitcher in the business.” Inexplicably the Boston Globe also mentioned his “good command” of the ball.43 The Boston papers crowed about his 16 victories in his last 18 starts; however, the real number was 10.44 The Phillies also took a look at signing Staley but withdrew, claiming he was an “undesirable man” with “uncertain habits.”45 Staley’s notoriety as a winning pitcher was followed closely by his reputation for intemperance.

Four days after signing with the Beaneaters, Staley debuted in a home game against Cincinnati. He gave up two runs in the first, but shut out the Reds for the next eight innings giving Boston a 7-2 victory. According to the Globe, Staley’s pitching performance “won his way into the hearts of all present.”46 In his next start, he also gave up two runs in the first, but this time Boston manager Frank Selee yanked him. John Clarkson relieved Staley but gave up eight more runs. The Globe howled at the “unfair movement” and the potential damage to Staley’s confidence.47 Clearly, the Globe was firmly in Staley’s corner.

The summer of 1891 proved that the Globe’s confidence was warranted. He held Brooklyn to just a double, a triple, and one run in an 8-1 win over the Grooms, pulling Boston up to second place.48 Staley closed out June by holding Brooklyn to one run.49 Staley’s curves continued to “baffle” teams into July and August.50 New York could manage only six scattered hits off him on July 27, the Phillies managed only eight in a 1-0 shutout on August 1, and only four Cincinnati players connected on August 5.51 As Boston held on to second place, the Globe proudly crowed that visiting teams were helpless against Staley.52 The Pittsburg press looked on in disgust at Staley’s performance and the Pirates’ own 33-52 record. “Certainly if there ever was a stupid transaction in baseball it was the releasing of Staley,” wrote the Pittsburg Dispatch.53

As Staley and the Beaneaters entered September, they were firmly in second place behind the Chicago Colts. Two losses to the Colts put them seven games out. By the middle of September they were able to cut that to five, and then on September 18 the Beaneaters began a 17-game winning streak including four doubleheader sweeps. In a September 30 home game against the Giants, Staley shut out New York for six innings until “rupturing an artery” after being struck in the face by a batted ball in the sixth. It ended his season.54 Despite losing Staley, Boston was now in first place and would remain there over the last three games of the season. As a Beaneater, Staley won 20 games and lost 8.

The 1892 Beaneaters lineup largely remained intact from the previous year including their pitching rotation. Staley, Kid Nichols, Jack Stivetts, and John Clarkson led the team to a 102-48 record and another championship. With the exception of a few days in July, Boston was in first place the entire season. Staley began the season in rare form, winning his first eight starts.55 His first loss did not come until a 10-inning 3-2 loss to St. Louis in June.56

August of 1892 brought trouble in the box. A 6-0 loss to Pittsburg featured dreadful fielding by Staley, one writer observing that he looked “like a man with wooden legs.”57 A week later he reportedly put “no life into his work” in a 6-1 loss to Cincinnati.58 In September Staley was reportedly suffering from an arm injury, and there were no signs of improvement in his pitching by the end of the month.59 In 1892 the National League experimented with declaring a champion for each half of the season. The two champions would then play a five-game series to determine the League champion. Staley pitched in the second game of the championship series, giving an “unsteady” performance that nearly lost the game if not for the Beaneaters’ superb defensive work.60 The Beaneaters were season champions, and despite the late-season injury, Staley ended with 22 wins and a 3.03 ERA.

Staley, Stivetts, and Nichols returned for the 1893 season after John Clarkson left the previous summer. While the Boston rotation remained steady, the rules of pitching changed dramatically. The modern pitcher’s mound replaced the flat pitcher’s box, raising the pitchers several inches above the batter. The distance between pitcher and home plate also was increased to the modern rule of 60 feet 6 inches. The two significant changes required a great deal of adjustment for pitchers, including Harry Staley.

The rule changes, however, were not the first hurdle for Staley. The pitcher failed to report to spring training on time.61 When he finally did appear, he was in poor shape. By May his condition was still substandard. The papers blamed the new pitching rules for his dreadful showing on May 2, but his weight and overall health did not help.62 The entire month of May 1893 was a disaster for Staley. He was “woefully out of trim” and it appeared his primary weapon, his curve, was gone.63 In a 13-12 win over Washington, Staley gave up 16 hits in four innings before being pulled.64 Rumors began to appear in the papers that a trade for better pitching was in the works.65

June saw little improvement in Staley’s pitching; however, on June 1, he had the greatest day of his career at the plate. In a 15-14 win over Louisville, Staley was responsible for nine Boston runs, with two home runs, a single, and two sacrifice hits. On the mound he was still in the wilderness, but his bat more than made up for it that day.66 But a week later, Staley gave up 15 hits, walked six, and threw four wild pitches in an 11-9 loss to Cincinnati.67 Plainly, Staley was still in need of conditioning or time to get accustomed to the new demands of pitching.

The Boston Globe reported on June 12 that Staley was living in Woburn, 12 miles from Boston, with the solid-hitting Boston shortstop, Herman Long. Their spare time was now spent with more subdued activities than the seductions offered by Boston.68 About this time, Staley’s fortunes on the mound began to turn. As June turned to July, his speed and control returned. In a 12-5 win over St. Louis on July 1, Staley gave up only three earned runs with two strikeouts. The victory put Boston in first place by one game over Philadelphia but the team slipped back into second by July 7.69

The team struggled along with Staley at the beginning of the 1893 season. But despite giving up 16 hits in a 7-4 loss to Philadelphia in July, Staley’s pitching largely regained its effectiveness as the Beaneaters charged into the final months of the season.70 Once moving back into first place at the end of July, the Beaneaters never retreated, holding a lead of 13 games at one point but never less than five. The papers raved about the pitcher’s performances. He was now in “prime condition,” with his curves again mystifying the opposition.71 Staley ended the season 18-10 with a 5.13 ERA. His early-season struggles were evident in the much higher ERA and the eight games in which he was pulled off the mound.

Three straight pennants for the Beaneaters increased the monetary expectations of several players, and so the 1894 season began with Staley and four others holding out for more money. An abundance of pitchers and his poor showing in the spring of 1893 potentially left Staley’s neck on the chopping block.72 By the beginning of April Staley and the team came to terms and another pitcher, Hank Gastright, was released.73

Staley began the 1894 season poorly, and there was no recovery this time. The Beaneaters used him sparingly; he started only 21 games and finished 18. Staley finished 12-10 with a 6.81 ERA. His fielding was “miserable,” and he began losing his control and speed late in games, giving up multiple hits. By July the press believed Staley was no longer a quality pitcher. He also gained weight over the summer, his body in no condition to play baseball. The press began referring to him as the “rotund Boston pitcher” and the “fat twirler.”74 According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, Staley became unpopular with the Boston sportswriters and the public because of what the public perceived as lackluster effort. The irascible Staley responded to the criticism by just giving up.75 Boston finished in third place. To no one’s surprise, the Beaneaters released Staley after the season.76

Staley was not adrift for long. The St. Louis Browns signed him in January of 1895. Over the winter, Staley shrugged off the obnoxious end to the 1894 season and also shed about 50 pounds. St. Louis manager Al Buckenberger called Staley the “catch of the year,” and owner Henry Killilea informed St. Louis fans “there is nothing the matter with his arm” and that “there is lots of good pitching in that fellow yet.”77 Clearly, these were the words of a promoter urging excitement in the face of his previous losing seasons.

Staley pitched mediocre ball for St Louis. His ERA for 1895, 5.22, was better than the previous year; however, he was routinely pulled from games as the other teams easily batted his pitches around the field. His weight and off-the-field activities made mediocre pitching worse and endeared him to no one. The Sporting News reported repeated “lushing” within the Browns lineup, with Staley one of the “chief offenders.”78

The Browns released Staley at the beginning of August. The Sporting News reported that he was struggling with rheumatism in his feet. There were rumors of offers from Philadelphia and Cincinnati, but they never materialized.79 Between the pain in his feet, his weight, and his drinking, Staley’s career in the major leagues was over.

Staley returned to Springfield and the bedside of his ailing brother shortly after his release. While he was there, a telegram arrived from Wheeling, West Virginia, seeking his help. The Wheeling Mountaineers of the Class-C Iron & Oil League were five games back in their pennant race and needed the services of Staley, whom they considered a “crack twirler.”80 The team was led by Jack Glasscock, a former National League infielder. Glasscock had taken to recruiting older National League players for Wheeling, which the Boston Globe called a “last resort of the ‘has-beens.’”81 Staley came to terms with the team and the Mountaineers sent the pitcher a train ticket. Staley arrived on August 24 and stayed with the team through the end of the season. The Mountaineers won the pennant.82

Staley signed with the Toronto Canadians of the Eastern League and his former St. Louis manager Al Buckenberger for the 1896 season. His pitching was occasionally solid, but a lack of control continued to plague him. The team, which finished the season playing in Albany, New York, and with a winning record, brought Staley back for the next season. However, Staley continued to decline. At the end of August 1897 he had an 8-11 record with a team filled with younger and more successful pitchers. The team released him.

Staley found a spot on the Norfolk (Virginia) club of the Class-B Atlantic League for a brief time in 1898, but his pitching career was essentially over. He settled in Pittsburg after leaving the game and worked at a paper factory. In 1910 the 43-year-old pitcher checked into the Battle Creek Sanatorium in Michigan with a stomach ailment. Doctors attempted surgery on January 12, but Staley died after the procedure.83

The same six modest lines announcing his death on January 12, 1910, in his hometown newspaper ran in several other papers across the country. While Boston papers did not even mention his death, six years earlier the Globe gave a small tribute to the former Beaneater. It called him an “honest workman” who “left no enemies in the baseball fraternity.”84 Staley was a successful pitcher at a time of great upheaval in the game. He eagerly supported the idea of players’ rights, struggled through the evolving pitching rules, and became one of many players struggling with off-the-field behaviors as the game tried to clean up its image with fans. Despite team and personal efforts to reform, Staley’s curve and career succumbed to alcohol and the indulgences offered the stars of the game.

Notes

1 1870 US census, Sangamon County, Illinois, population schedule, Springfield, 531, William and Emily Staley; digital image, Ancestry.com, accessed November 25, 2017, ancestory.com.

2 Michigan, Death Records, 1897-1920, Emily Virginia Staley.

3 “Staley and Beckley,” The Sporting News June 23, 1888: 1.

4 Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010), 358.

5 “Staley Signs With Boston,” Boston Globe, May 27, 1891: 5; “Staley and Beckley,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1888: 1. In the papers of the time period, Pittsburgh was spelled without the ‘h.’

6 “Games of June 30,” The Sporting News July 7, 1888: 2; Some sources credit him with one strikeout, some with five. Four is the number printed in the cited edition of The Sporting News.

7 “Staley and Beckley,” The Sporting News June 23, 1888: 1.

8 “National League,” The Sporting News July 21, 1888: 2.

9 Ibid.

10 “Pittsburg and Chicago Play Two Exciting Games,” Boston Globe August 23, 1888: 5.

11 “Pittsburg, 7; Washington, 2,” Boston Globe September 9, 1888: 5; “Washington, 8; Pittsburg, 3,” Boston Globe, September 14, 1888: 5.

12 “Murnane’s Message,” Boston Globe, September 10, 1888: 8.

13 Baseball-Reference.com; “Reserved for Next Year,” New York Times, October 19, 1888: 3.

14 “Sporting Review,” Pittsburg Dispatch, January 13, 1889: 6.

15 “Baseball Matters,” Pittsburg Dispatch, January 29, 1889: 6; “Staley Will Stay,” Pittsburg Dispatch, January 14, 1889: 6.

16 “A Strange Story,” Pittsburg Dispatch, February 10, 1889: 6.

17 Ibid.

18 “Sporting News,” Pittsburg Dispatch, February 12, 1889: 6.

19 “They Must Be Good,” Pittsburg Dispatch, March 12, 1889: 6.

20 “The Last Skirmish,” Pittsburg Dispatch, April 23, 1889: 6.

21 “Easy Victory,” Boston Globe, May 14, 1889: 5; “A Close Argument,” Pittsburg Dispatch, May 16, 1889: 6.

22 “With Little Glory,” Pittsburg Dispatch, June 1, 1889: 6.

23 “Not Losing Money,” Pittsburg Dispatch, June 10, 1889: 6.

24 “Mickey’s Measure,” Pittsburg Dispatch, July 6, 1889: 6.

25 “Gone to the East,” Pittsburg Dispatch, July 8, 1889: 6.

26 Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 221.

27 “A Break at Last,” Pittsburg Dispatch, November 27, 1889: 6.

28 “Busy Brotherhood,” Boston Globe, December 17, 1889: 8.

29 “Staley Heard From,” Pittsburg Dispatch, February 18, 1890: 6.

30 “New Club Gossip,” Pittsburg Dispatch, April 7, 1890: 6; “Pitcher Staley Arrives,” Pittsburg Dispatch, March 20, 1890: 6.

31 “In Fourth Place,” Pittsburg Dispatch, July 9, 1890: 6; “New York, 10; Pittsburg, 2,” Boston Globe, July 19, 1890: 5.

32 “A Pitcher’s Battle,” Pittsburg Dispatch, July 27, 1890: 6.

33 “Released for Drinking,” Pittsburg Dispatch, August 9, 1890: 6.

34 “‘Kareless’ Kilroy,” Boston Globe, August 29, 1890: 5.

35 “It Was So Very Easy,” Pittsburg Dispatch, September 30, 1890: 6.

36 “A Review of Sports,” Pittsburg Dispatch, September 21, 1890: 14.

37 “Notes of the Diamond,” Wheeling Register, October 12, 1890: 3.

38 Seymour, 244.

39 “Next Year’s Teams,” The Sporting News, January 24, 1891: 1; “Diamond Dust,” Wheeling Register, February 1, 1891: 3; “An Inglorious End,” The Sporting News, January 24, 1891: 1.

40 “A Call to Magnates,” Pittsburg Dispatch, March 25, 1891: 6.

41 “Baseball Brevities,” New York Times, May 23, 1891: 3.

42 “Staley Signs With Brooklyn,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 26, 1891: 3.

43 “Staley Signs With Boston,” Boston Globe, May 27, 1891: 5.

44 Ibid.

45 “Couldn’t Touch Staley,” Boston Globe, August 6, 1891: 5.

46 “Off His Fodder,” Boston Globe, May 31, 1891: 4.

47 “Tried Two Pitchers,” Boston Globe, June 3, 1891: 5.

48 “Two Games for Boston,” New York Times, June 18, 1891: 8.

49 “Brooklyn, 4; Boston, 1,” New York Times, July 1, 1891: 3.

50 “Staley Unfathomable,” Boston Globe, July 22, 1891: 5.

51 “Staley Puzzled Them,” Boston Globe, July 28, 1891: 5; “Giants in Third Place,” New York Times, August 2, 1891: 8.

52 “Couldn’t Touch Staley,” Boston Globe, August 6, 1891: 5.

53 “A Review of Sports,” Pittsburg Dispatch, August 9, 1891: 18.

54 “Boston Takes Lead,” New York Times, October 1, 1891: 6.

55 “Like a Ghost,” Boston Globe, May 31, 1892: 16.

56 “Staley’s First,” Boston Globe, June 4, 1892: 5.

57 “Staley’s Off Day,” Boston Globe, August 20, 1892: 5.

58 “Kelly Weakened,” Boston Globe, August 31, 1892: 5.

59 “Narrow Escape,” Boston Globe, September 29, 1892: 5.

60 “Duffy’s Batting,” Boston Globe October 19, 1892: 2.

61 “Two Men Not Yet Signed,” Boston Globe, April 2, 1893: 2.

62 “All Is Chaos,” Boston Globe, May 3, 1893: 6.

63 “Out of Trim,” Boston Globe, May 10, 1893: 5; “Three Straight,” Boston Globe, May 18, 1893: 2.

64 “Boston’s Day,” Boston Globe, May 27, 1893: 6.

65 “Where Will Kelly Go?” Boston Globe, May 12, 1893: 5.

66 “Very Much in It,” Boston Globe, June 2, 1893: 2.

67 “Dropped a Peg,” Boston Globe, June 9, 1893: 3.

68 “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, June 12, 1893: 9.

69 “Boston in First,” Boston Globe, July 2, 1893: 7.

70 “Won the Third,” Boston Globe, August 3, 1893: 2.

71 “Staley in Form,” Boston Globe, August 11, 1893: 6.

72 “Tucker’s Grievance,” Boston Globe, March 25, 1894: 7.

73 “Boston’s Ball Players,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 3, 1894: 3.

74 “Staley Slows,” Boston Globe, September 9, 1894: 2.

75 ‘Chat and Comment,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 19, 1895: 4.

76 “Baseball Notes,” Washington Post, December 30, 1894: 6.

77 “Pitcher Staley Signed by Browns,” Boston Globe, January 9, 1895: 2; “Chat and Comment,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 19, 1895: 4.

78 “A Dead Issue,” The Sporting News, June 9, 1895: 1.

79 “Henry E. Staley,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1895: 5; “Baseball Notes,” Washington Post, August 14, 1895: 6.

80 “Baseball Comment,” Wheeling Register, August 20, 1895: 4.

81 “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, September 11, 1895: 4.

82 “Baseball Comment,” Wheeling Register, August 21, 1895: 4.

83 “Harry Staley Is Dead,” Kansas City Star January 13, 1910.

84 “Harry Staley,” Boston Globe, July 10, 1904: 36.

Full Name

Henry Eli Staley

Born

November 3, 1866 at Jacksonville, IL (USA)

Died

January 12, 1910 at Battle Creek, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.