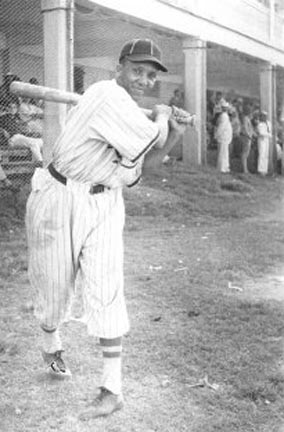

Horacio “Rabbit” Martinez

Horacio “Rabbit” Martínez (1912-1992) was the prototype for the long line of shortstops from the Dominican Republic: slick-fielding, quick, and a threat on the basepaths. He had an outstanding career in the Negro Leagues with the New York Cubans (1935-36, 1939-47). Though professional ball was largely absent in his homeland while Martínez was active, he still played there, as well as Cuba, Venezuela, and Puerto Rico. Toward the end of his career, he was also a player-manager in Panama.

Martínez got his nickname from his speed.1 He could hop like a rabbit too, as noted Pittsburgh photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris showed. At 5-feet-9 and 155 pounds, he was a classic light-hitting glove man. Yet even though he was not a powerful batter, his superb defense brought him to the Negro Leagues’ East-West All-Star Game five times: 1940, 1941, 1943, 1944, and 1945. In that showcase, among a host of the greatest players from that or any era, he batted .545 (6-for-11). 2

Had Martínez’s African descent been a little less obvious, he might have been able to perform in the majors. In Cuban Star, a full biography of Hall of Famer and Cubans owner Alex Pómpez, author Adrián Burgos, Jr. gave insight into Rabbit’s situation. “As a reflection of the capricious policing of baseball’s racial divide, thirteen Latinos would perform in both the black baseball circuit and the major leagues during this Jim Crow era [1902-1945]. . .the key to this group’s participation in the segregated majors was the public portrayal of them as not being U.S.-born blacks.

“Horacio Martínez. . .felt the impact of this truth. In 1943, sportswriters offered his name as a potential barrier breaker in the majors. The Daily Worker writer Nat Low cited the Brooklyn Dodgers as a possible destination, given its ‘weakness’ at shortstop. Mistakenly referring to Martínez as ‘first, last, and always a Cuban, the Norfolk Journal and Guide writer Lem Graves noted that there were ‘plenty of Cubans playing big league baseball, no fairer than Martínez.’ The problem, as was the case with dozens of other Latino players, was Martínez’s hair. That was what Pómpez informed the sportswriter, admitting to previous opportunities to sell Martínez to the Washington Senators or other clubs ‘if ‘Rabbit’ had possessed the slick hair.’”3

Although his playing days came too early, Martínez’s legacy to the big leagues as a scout is extremely significant. Alex Pómpez went to work for the New York Giants in 1950, after folding his Cubans team. He hired Martínez as a bird dog, and Rabbit eventually became the Giants’ head scout in Latin America after Pómpez died in 1974. His signal accomplishment was helping to bring in the first wave of Dominican major-leaguers — men like the Alou brothers, Juan Marichal, and Manny Mota.

Horacio Antonio Martínez Estrella was born on October 20, 1912 in Santiago, the second-largest city in the Dominican Republic. His parents were Antonio “Toño” Martínez and Ana Rita Estrella. As is true of many ballplayers (not least Dominicans), there has been uncertainty about both the year and place of his birth. Some sources show 1915, and there are suggestions that the place was San Pedro de Macorís, the city that has provided many Dominican shortstops, or Santo Domingo. However, the Hall of Fame of Dominican Sports (which inducted Martínez in 1970 as part of its fourth class) shows the 1912 date and Santiago.

The Martínez family had four boys and five girls. All of Horacio’s brothers — Toñito, Aquiles, and Julio — also became prominent baseball players in their homeland.4 In his late teens, Horacio became part of the team called General Trujillo, after the Dominican president/dictator, who had taken power in 1930. The squad traveled through the Caribbean and Central America during 1931 and 1932. In 1933 and ’34, Martínez was shortstop for the Licey Tigres. Licey (main color: blue) and the Escogido Leones (red) are the two longest-running and best-known Dominican teams. At that time, though, the nation did not have a professional league.

Martínez married Idalia Tejeda Burgos from Santo Domingo in March 1935. The couple eventually had three children: Horacio Augusto, Roberto Pedro Antonio and Mirtha Altagracia. Shortly after his marriage, Horacio and another outstanding Dominican, catcher Enrique “El Mariscal” Lantigua, joined the New York Cubans. They were the third and third fourth of their countrymen to play in the Negro Leagues, after pitcher Pedro Alejandro San (who debuted with Pómpez’s Cuban Stars in 1926) and Juan “Tetelo” Vargas, who is regarded as the most notable early Dominican player. Among the other first-rate players on the 1935 Cubans were Hall of Famer Martín Dihigo, Alejandro Oms, Luis E. Tiant, and Manuel “Cocaína” García.

In the winter of 1935-36, Martínez played pro ball in Cuba for the first time. He joined Santa Clara, featuring player-manager Martín Dihigo — but had to play second base, because the shortstop was another Hall of Famer, Willie Wells.5 Rabbit spent all or parts of seven winters in Cuba from 1935 through 1944, not including 1938-39 and 1939-40. He hit .258 with one homer and 92 RBIs in 978 at-bats, mainly for Santa Clara and Habana (he also played briefly for Almendares).

In 1936, spring training for the Cincinnati Reds featured a voyage to Puerto Rico. Toward the end of the trip, the Reds split their squad, sending a group of 16 players to Ciudad Trujillo (as Santo Domingo was known from 1936 to 1961) to play Dominican teams on March 3 and 4.6 The Reds swept Escogido and Licey, 7-1 and 4-2. Martínez — listed in the U.S. box score as “Horacio” — played for Licey. He was 2-for-4, though he also committed two errors.7

The New York Cubans did not operate during the 1937 or 1938 seasons. Special prosecutor Thomas Dewey had Alex Pómpez in his sights for involvement with the numbers racket in New York, and Pómpez hid out in Mexico for a portion of this time. His players, Martínez among them, looked mainly to Latin America for employment.

As has often been chronicled, 1937 was a remarkable year in Dominican baseball. The 1991 book by Rob Ruck, The Tropic of Baseball, gives an account featuring firsthand memories from people who were there. Rafael Trujillo was not a baseball fan (though his son Ramfis was); he really loved horse racing. Yet the Generalissimo was not happy because the 1936 championship had gone to San Pedro de Macorís, and the people around him were typically seeking greater glory for the dictator. Furthermore, baseball was a populist tool in Trujillo’s hands — the 1937 professional season was dedicated to his re-election.

Thus, Ciudad Trujillo assembled a powerhouse. Licey, for whom Martínez had played in 1936, and Escogido were combined. Furthermore, the best Negro Leaguers of the day were lured to come down and play. The Dragons’ list of luminaries included Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, “Cool Papa” Bell, and more. Many of the Negro Leaguers actually came down relatively late in the series, which ran from March to July; they displaced Dominicans and Cubans. The proportion of native players in the league that year wound up being low — but Martínez was there throughout, playing for Santiago.8

The dean of Dominican baseball writers, Emilio “Cuqui” Córdova, focused exclusively on the events of the 1937 season in the 17th book of his series Historia del Béisbol Dominicano.9 An earlier installment was devoted to Horacio Martínez, though unfortunately that fuller biography was not available as a source for this story.10

After the excesses of 1937, official pro baseball went on hiatus in the Dominican Republic for 14 years. Nonetheless, following the collapse, Martínez played for Licey when that club reformed.11 During this time, he also played in his homeland against visiting teams (from Puerto Rico, for example) and in the Inter-Antillean Series with Cuba and Puerto Rico. Also, during the years that there was no professional league play, baseball remained the sport of choice for Dominicans. Contests continued in the nation and Martínez was a frequent participant.

He also ventured elsewhere in Latin America. A book called Historia del Béisbol en el Zulia, which focuses on the game in Venezuela’s westernmost state, notes that he and Cuban shortstop Silvio García came down in 1937 to play with the Pastora club.12 Rabbit remained with Pastora in 1938, taking part in a memorable 20-inning game on June 5. The winning pitcher, fellow Dominican Andrés Julio Báez, went all the way in the six-hour, twenty-minute battle and scored the game’s only run.13 Báez was known as “Grillo B” — he was the middle brother of three “Crickets” who are all in the Hall of Fame of Dominican Sports.

Martínez also played 11 games for Vargas in Venezuela in 1938, going 9 for 49 (.184) with one RBI. Furthermore, he reinforced the Ponce Leones in Puerto Rico’s inaugural season of winter baseball, 1938-39. Until 1941, that circuit did not have full professional status — it was known as La Liga de Béisbol Semiprofesional de Puerto Rico (LBSPR).14 Although Martínez’s name does not appear in Enciclopedia Béisbol Ponce Leones, 1938-1987 by Rafael Costas, Puerto Rican League historian Jorge Colón Delgado has confirmed that Rabbit was there (statistics remain under investigation).15

Alex Pómpez was back in baseball in 1939, and so were his New York Cubans. Martínez rejoined the roster. In June and July 1939, however, a series took place in Ciudad Trujillo between the Dominican Republic (represented by Licey and Escogido) and Puerto Rico (represented by the Ponce Leones). “Licey walked away with the championship trophy and Horacio Martínez was the top hitter in the competition.”16 This followed an earlier series in Puerto Rico, which featured Licey against Ponce and San Juan.17

Here and there Martínez attracted attention from the mainstream U.S. press. In July 1942, ahead of a doubleheader against the semipro Brooklyn Bushwicks at Dexter Park, the New York Times singled him out for praise, saying, “The Cuban Stars have been traveling at a fast pace since Horacio Martínez took the shortstop role a month ago.”18 The previous day, the Brooklyn Eagle had explained that Martínez joined the club late because he could not get transportation north for six weeks.19

Perhaps the real reason was the same as what took place in 1943, when Martínez also reported late to the Cubans. As the New York Post wrote that May, Rabbit had ignored Alex Pómpez’s cables because he had been making good money at home in the Dominican Republic — but changed his mind, allegedly because he had been hitting Trujillo’s favorite pitcher too well.20

In July 1943, the Cubans headed upstate to play the Niagara Falls Days at Hyde Park Stadium (later renamed for local hero Sal Maglie). The Niagara Falls Gazette wrote, “Horacio Martínez, at shortstop, continues to show why he is rated without a peer at that position. Speedy and sure, Martínez has come up from the Dominicans of Cuba [sic] rated by far the best shortstop from that island since the great Checon [sic], although many critics maintain he is the equal of the latter.”21 The doubly confused comparison was with Pelayo Chacón, the Cuban who had also been a longtime star in the Negro Leagues, and whose son Elio became a major-leaguer.

A day previously, the Gazette had written that Martínez, “sensational shortstop,” along with Dave “Impo” Barnhill and Roy Campanella (misspelled as “Campinello”), had been in line for a 1942 tryout with the Pittsburgh Pirates that never materialized.22 Neil Lanctot’s biography of Campanella details how Pirates owner William Benswanger initially encouraged the notion, then backed down — but this account does not mention Martínez as one of the candidates.

Stanley Glenn, a star catcher who broke into the Negro Leagues with the Philadelphia Stars in 1944, told author Brent Kelley that he viewed Martínez as a Hall of Fame player. “He was a better hitter than [Phil] Rizzuto; he was also a better fielder. He could pick it, my friend.”23 Another Negro League chronicler, William McNeil, wrote, “Martínez was a defensive wizard of the caliber of Ozzie Smith. He had speed, grace, exceptional intuition, a sure glove, and a rocket for an arm. He was generally recognized as the best shortstop in the Negro Leagues during the late ’30s and early ’40s.”24

Glenn was giving Rabbit too much credit with the stick. William McNeil also wrote, “The chink in Martínez’s armor that kept him from becoming an all-time great was his weak bat. During his Negro League career his average hovered around the .230 mark.”25 Negro League records are patchy, but the general indication is in keeping with the more complete Cuban data. Rabbit compensated to some degree, however, with “small ball” skills. In his Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, James A. Riley wrote that Martínez was “a good bunter, fast on the bases, and good on either end of the hit-and-run play. . .Always a hustler.”

Martínez was also a leader. At some point he became a manager; possibly the first time he did so was during the Inter-Antillean Centennial Series of 1944. This tournament commemorated the 100th anniversary of the Dominican Republic’s independence from Haiti. Rabbit and Manuel Henríquez co-managed the home team, which upset Cuba — only the third time Cuba had lost an international competition in 20 years.26 Martínez also managed his national team during the Amateur World Series of 1944, but the seventh edition of this tournament was marred by various protests. One of them came from Martínez in a loss to Cuba; he objected to the improper use of pinch-hitters.27

In the winter of 1945-46, Venezuela established its main professional baseball league. Martínez came down to play for Patriotas de Venezuela, going 14 for 52 (.269) in 13 games with no homers and seven RBIs.28 That winter he also served as a player-manager in Panama. According to Dominican sources, the team was Colón; if so, that club was in the Canal Zone League, and boasted Cardinals center fielder Terry Moore. On January 3, 1946, however, the Panama Professional League began play with 28 players imported from Mexico, the U.S., and Cuba. This four-team circuit, which the Sporting News compared to Class-B ball, could have been the one Martínez joined.29

As Rabbit’s career with the New York Cubans wound down in 1946 and 1947, Alex Pómpez brought in a variety of notable players. One of them was Orestes Miñoso, later known as “Minnie,” who played third base in 1946. The shortstop that year was Silvio García, who pushed Martínez over to second base. García jumped to the Mexican League that summer, however, as Jorge Pasquel was luring many players south of the border with bigger money in his bid for major-league status.

Rabbit returned to the Panama Professional League in the winter of 1946-47 to play for Cadena Panameña de Radiodifusión. In 1947, with much of the luster gone from the Mexican scene, Silvio García came back to New York. There is no conclusive evidence that Martínez ever played in Mexico himself.30 However, he concluded his U.S. career with a championship, as the Cubans (Negro National League) defeated the Cleveland Buckeyes (Negro American League) in the Negro World Series. What may well have been his final games as a pro came with Panama’s Cervecería Nacional in 1947-48.

On Sunday, January 11, 1948, Dominican baseball suffered its greatest tragedy — an event that affected Horacio Martínez directly. A twin-engine plane flying from Barahona (in the southwestern part of the republic) to Santiago (in the central Cibao region) crashed into the Río Verde mountains. Except for catcher Enrique Lantigua, who had a premonition and drove instead, the entire Santiago club perished. That included Toñito and Aquiles Martínez, the former a popular catcher and the latter a fine-fielding second baseman. Julio Martínez, the club’s teenaged mascot, also escaped because his own team had scheduled a game.31

The 1949 edition of the annals of the University of Santo Domingo showed that Martínez was employed there as a sports instructor (i.e., baseball coach). He eventually became the university’s athletic director, occupying that job while he was scouting for the Giants. Felipe Alou, a pre-med student, was his cleanup hitter in 1955.

On December 28, 1956, Martínez managed his homeland’s team against a squad of U.S. players in the Dominican League’s All-Star game. The Dominican fans, who selected both teams, extended a special invitation to Eddie Lopat to come out of retirement and pitch. Lopat hurled the first two innings and got the win; Bill Mazeroski had the game’s only homer. The yanquis were managed by John “Red” Davis, a minor-league skipper for the Giants who was then also managing Escogido (a sign of the ties between Horace Stoneham’s franchise and the Dominican Republic).32

Martínez was a coach for Escogido; he also managed Licey for three games in 1951, the first season of the current Dominican League. In addition, he continued to manage the Dominican national team in amateur competition. One example was the 1959 Pan-American Games, held in Chicago.33 Although the Dominicans finished eighth with a record of 2-3, a powerful young man named Rico Carty (who turned 20 during the tournament) made a strong impression on U.S. scouts. He was spotted by Milwaukee Braves scout Ted McGrew and soon thereafter went on to become another early Dominican big-league star.

Although Martínez did not sign Carty, he did land quite a few other players for the Giants besides the Alous and Manny Mota. Among the men who made it to the majors were José Vidal and Freddie Velázquez (who signed in 1958), Ricardo Joseph (1959), Pepe Frías (1966), Rafael Robles (1967), and Elías Sosa (1968). Sosa was the only one of them who played for the Giants, though. Perhaps for that reason, over time the franchise’s interest in Dominican talent waned. Yet the great players whom Martínez signed felt immense loyalty and respect toward him. In July 1993, Juan Marichal described the poignant end of Rabbit’s scouting career to authors Marcos Bretón and José Luis Villegas.

“When other scouts were earning twenty-five thousand and thirty thousand dollars a year, Horacio was only earning nine thousand dollars. So when the Giants were looking to liquidate some of their scouting positions, they were going to retire Horacio at half his salary. I was out of the organization but the Giants asked my opinion and I told them they should retire Horacio at his full salary because he didn’t even earn a third of what other scouts were earning. And so they did, but [before that] when the Giants offered me a job [in the late 1970s] they were going to release him but I didn’t permit that. For me, Horacio was like a father and I wasn’t going to take his job away from him. He was the best scout they ever had.”34

In later life, Martínez suffered from Parkinson’s disease. Rob Ruck offered a moving depiction in The Tropic of Baseball. “Horacio Martínez, 77, is confined to a wheelchair in his Santo Domingo home. . .the once-graceful shortstop now can hardly speak. While struggling to describe his career to me on an earlier trip, Horacio Martínez’s eyes had filled with tears, brought on by frustration. I make the mistake of telling Julio about his brother’s efforts and the Aguilas coach excuses himself. He walks down the first base line into the right field corner where he sheds tears of his own.”35

Horacio Martínez died on April 14, 1992. The following year, a powerful testament to his importance came from another of the most eminent Dominican baseball figures, Felipe Alou. Alou told Marcos Bretón and José Luis Villegas how much Martínez meant to him personally.

“There are American black players who have been elevated to the Hall of Fame, who have been recovered from the forgotten, and that work has been done by Americans. But we don’t have and will never have that kind of representation to promote a Horacio Martínez. He wasn’t just some scout. He was a great athlete and he spoke a great deal to me before I left to play in the United States. This was back in the 1950s when there was so much racism in the United States, but I came here aware of all those things because I had a great teacher. I was his first player signed to make it to the big leagues and for me, it was like I was on a mission.”36

Alou expanded on this theme with Rob Ruck. When he was in his first pro season with the Giants, and encountered racism on a long bus trip in the Deep South, young Felipe was tempted to quit and go back home. Instead, “I thought about Horacio Martínez, not so much my mom and dad. I didn’t want to let him down and I stayed.”37 Alou in turn then became an inspiration to many Dominicans.

Echoing Marichal and Alou, Manny Mota offered his own personal tribute in 2012. In a firm and even tone, he emphasized, “Mr. Horacio Martínez was without a doubt one of the greatest players in the history of the Dominican Republic. Besides being a great player, he was like a father to me. I’ve got a great deal of respect and admiration for him.”38

In 2005, Martínez became one of 94 preliminary candidates named by the Hall of Fame’s Special Committee on the Negro Leagues. The process had changed since Felipe Alou had talked about it in 1993 — there was at least some Latino representation among the wealth of prominent figures. The screening committee also included an expert on Latin America in Adrián Burgos. In 2012, Burgos discussed what happened with Martínez’s candidacy.

“The five members of the nominating committee39 voted on narrowing down the list. Each nominee had to meet the three-quarters of the vote threshold that the Hall requires for induction; 39 made that cut. The lack of stats and more than some testimonials from a few Negro Leaguers hurt Horacio’s chances. For certain, we knew he was a fantastic fielder, but there was no Gold Glove award or a poll of the greatest fielders of the Negro Leagues. That also limited his chances.”40

A few years after the Special Committee election, however, the Latino Baseball Hall of Fame (El Salón de la Fama del Béisbol Latino) was formed to recognize great Hispanic players. As part of its second class, announced in October 2010 and inducted in 2011, Horacio Martínez was named by the Hall’s Veterans Committee. This institution is located in the Dominican Republic, and Martínez became the fourth Dominican honored. He followed Tetelo Vargas — and his two special protégés, Felipe Alou and Juan Marichal. Yet, as this kind, modest man said in 1975, “I have no complaints about life and although I have no money, it is my personal satisfaction of having always been an honest person.”41

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Peggy Fukunaga for contributing insights from her research on Dominican baseball, and to Rob Ruck for the introduction and his advice. Continued thanks also to Manny Mota and José Mota; Adam Chodzko, Media Relations, Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim; SABR members Alfonso Tusa, Jorge Colón Delgado, and Adrián Burgos; Jesús Alberto Rubio.

Sources

Books

Figueredo, Jorge S. Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003).

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues(New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994).

Gutiérrez, Daniel, Efraim Álvarez, and Daniel Gutiérrez, Jr. La Enciclopedia del Béisbol en Venezuela (Caracas, Venezuela: Editorial Norma, 2007).

Internet resources

Pabellón de la Fama del Deporte Dominicano (http://www.pabellondelafamadeportedom.com)

Edwin “Kako” Vázquez, “Horacio Martínez de Santiago Rep Dom,” 1-800-BEISBOL (http://www.1800beisbol.com/baseball/Deportes/Beisbol_Dominicano/Horacio_Martínez_de_Santiago_Rep_Dom/)

www.licey.com

Notes

1 Marcos Bretón and José Luis Villegas, Away Games: The Life and Times of a Latin Baseball Player, New York, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999, 51. Some sources indicate that he was also called “Millito,” but this may well be confusion with another player of the era named Luis Emilio Martínez.

2 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase (Lincoln, Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

3 Adrian Burgos, Jr., Cuban Star: How One Negro-League Owner Changed the Face of Baseball (New York, New York: Hill and Wang, 2011), 159-160.

4 Rob Ruck, Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game (Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 2011), 65.

5 Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 274.

6 “Red Rookie Trying to Emulate [Augie] Galan,” The Sporting News, March 5, 1936: 6.

7 The Sporting News, March 12, 1936: 10.

8 Rob Ruck, The Tropic of Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Publishing, 1991), Chapter 3.

9 Ubi Rivas, “Libro de Cuqui Córdova narra la calidad del torneo de 1937,” Hoy (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), October 24, 2009.

10 Cuqui Córdova, Horacio Martínez: El Rabbit (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: Revista Historia del Béisbol, 2004).

11 At some point in his career, he also played one season for Escogido.

12 Luis Verde, Historia del Béisbol en el Zulia (Maracaibo, Venezuela: Editorial Maracaibo, S.R.L.), 1999.

13 Cuqui Córdova, “ ‘Grillo B’ ganó un juego de 20 innings en Venezuela (05.06.1938), venciendo al zurdo cubano Lázaro Salazar 1 x 0,” Listín Diario (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), March 30, 2010.

14 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1995), 9.

15 Cuqui Córdova’s book also cites Puerto Rican sources, and Thomas Van Hyning also mentions in passing that Puerto Rican fans got to see Martínez.

16 William McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007), 147.

17 1939 newspaper reports in the Dominican newspaper La Opinión, as researched by Peggy Fukunaga.

18 “Bushwicks Meet Cubans,” New York Times, July 19, 1942.

19 “Dimout Law Again Saves Bushwicks,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 18, 1942: 10.

20 Stanley Frank, “Negro Ball Teams Carry On Despite All Difficulties,” New York Post, May 29, 1943: 34.

21 “Barley Definitely Slated to Pitch for Days Against Cubans Wednesday,” Niagara Falls Gazette, July 13, 1943: 13.

22 “New York Cubans Have Strong Team Here for Game Here Wednesday with Days,” Niagara Falls Gazette, July 12, 1943: 11.

23 Brent Kelley, Voices from the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1998), 155.

24 William McNeil, Baseball’s Other All-Stars (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2000), 174.

25 Ibid.

26 Cuqui Córdova, “Serie Interantillana Centenario 1944,” Listín Diario, December 17, 2011.

27 Rafael V. Peña, El Big Show Desde New York blog, November 14 and November 21, 2011 (http://www.radiario.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=368:radiario)

28 The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues incorrectly states that Martínez was player-manager for Caracas.

29 “Panama Pro Loop Begins Play,” The Sporting News, January 10, 1946: 16.

30 The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues also states that Martínez played winter ball in Mexico (La Liga de la Costa del Pacífico began play in the 1945-46 season). However, leading Mexican baseball researcher Jesús Rubio could not find any evidence of it. There is no entry for Martínez either in the reference on Mexican summer ball, La Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano, though there are gaps in that volume (for example, Hall of Famer Willard Brown).

31 Rafael V. Peña, “La Tragedia de Río Verde 1948,” El Día (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), January 11, 2011. Ruck, The Tropic of Baseball, 102.

32 Feliz Acosta Núñez, “Lopat Takes Hill, Helps U.S. Stars Decision Natives,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1957: 20.

33 Ruck, Raceball, 205.

34 Bretón and Villegas, 52.

35 Ruck, The Tropic of Baseball, 103.

36 Bretón and Villegas, 51-52.

37 Ruck, Raceball, 150.

38 Manny Mota, telephone interview with Rory Costello, May 21, 2012.

39 Rob Ruck was on the full 12-member voting committee.

40 Adrián Burgos, e-mail to Rory Costello, April 11, 2012.

41 Arturo Industrioso, El Caribe (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), June 21, 1975.

Full Name

Horacio Antonio Martínez Estrella

Born

October 12, 1912 at Santiago, (DR)

Died

April 14, 1992 at Santo Domingo, (DR)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.