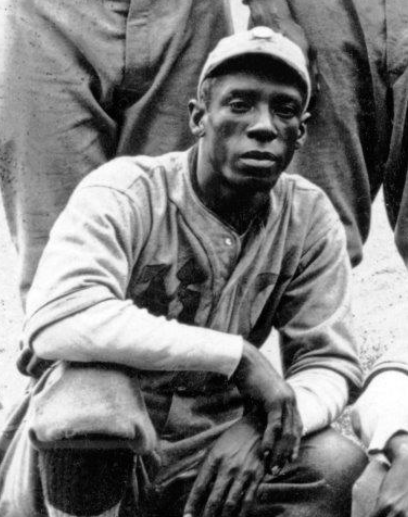

José Méndez

Among numerous icons from Cuba’s somewhat murky pre-revolution past, swarthy-skinned pitching ace José de la Caridad Méndez Báez stands at the very apex of the heap. Among the young nation’s first true national sporting heroes, the rawboned fastball hurler maintains an indelible image as one of the earliest icons of island baseball history. But it is a murky legend at best, one built largely upon an all-too-brief meteoric rise celebrated in subsequent years more for historical impact in his own fledgling nation than for any sustained diamond achievement. And in the long run some oft-ignored negatives would potentially cancel out many of the ballyhooed heroics repeatedly paraded in print by latter-day “Blackball” boosters among baseball’s many revisionist historians.

On the one hand there is the pesky legend surrounding one of the greatest of all underappreciated Negro league hurlers – an unhittable fireballing phenom who mesmerized visiting white big leaguers and in the process amplified the reputation and stoked the pride of the island’s still nascent national sport and its enthusiastic boosters. On the other hand there are all the perplexing questions about the true level of his achievements and the true merits of his meteoric career. If the byword of Cuban baseball – pre- and post-revolution – has so often been inescapable and distracting mystery, no figure remains more mysterious than the island’s first idolized Blackball pitching star.

Today the mere weight of the legend itself ironically casts a darkened cloud over Méndez and his actual sporting legacy. From the perspective offered by a full century separating his pioneering era from the present, there now seem to be many more troublesome questions than verifiable pieces of tangible evidence when it comes to measuring the actual ballplaying stature of this pioneering pitcher. His somewhat embellished saga indisputably occupies an indelible niche in Cuba’s early cultural and sporting history, yet his recent “belated” enshrinement in Cooperstown might seem to at least some purists more of an unwarranted sympathy vote than any mark of legitimate recognition. And the argument on Méndez’s behalf is not entirely helped by the fact that his 2006 election came via a one-time special ballot cast by a “Committee on African-American Baseball” charged with upgrading the Hall of Fame’s image regarding the treatment of pre-integration Negro league stars. That unorthodox (if perhaps needed) “rectification” balloting produced a mass enshrinement of 18 new selectees – the largest in the institution’s history – including the first woman (Effa Manley), 11 past Blackball greats, plus a quartet of pioneering Negro league owners, and early twentieth-century Cubans Méndez and Torriente. The original impetus had been a July 2000 grant awarded to the Cooperstown shrine and museum by Major League Baseball for the purpose of funding a comprehensive study on African Americans in the sport between 1860 and 1960, with the clear motive of enhancing the museum’s collections in this long-ignored area. One irony in the end was that a pair of the largest posthumous beneficiaries were not African-Americans at all but Afro-Cubans, an apparent nod to the crucial role played by Cuba in the early-twentieth-century Negro leagues saga.

If the Méndez plaque hung in Cooperstown’s gallery in the late summer of 2006 (almost precisely a century after his rather remarkable explosion on the Cuban winter league scene) is not among the least merited trophies in the North American National Baseball Hall of Fame, it might well be one of the most controversial. The Méndez feats – like those of fellow Cuban inductee Torriente – seem based heavily if not exclusively on but a handful of reportedly stunning winter-season exhibition outings versus touring (and thus vacationing) big leaguers.1 Those legendary outings have been time and again recounted and embellished without much careful examination of what they might actually have looked like at the time. Despite substantial Cuban league careers, neither Méndez nor Torriente ever maintained the universal accolades in their homeland that were attached to Cuba’s first Cooperstown honoree, Martin Dihigo, the first name usually raised when hot-stove discussions turn to picking the greatest all-around diamond performers from any league or era.2

What is nonetheless undeniable in the case of Méndez is the large impact his surprising exploits during the early winter months of 1908 and 1909 had on the Cuban baseball scene at the time. To understand that impact, one has to revisit the island baseball culture of the past century’s first decade. What must be grasped first and foremost is the political environment sweeping the island nation in the immediate aftermath of the misnamed Spanish-American War and during an American military occupation that immediately followed. The hostilities that came to an end with Teddy Roosevelt’s charge up San Juan Hill in 1898 were the culmination of three decades of rebellion against the ruling Spanish. But they also closed out a three-decade Cuban struggle for national sovereignty eventually co-opted with a US intervention that merely resulted in trading one colonial master for another. Also vital to the story is the earliest role of the “American” sport on the island and its impact on the young county’s sense of national identity. Touring American professionals – white big leaguers and barnstorming Negro leaguers – began visiting Havana late in the nineteenth century and such visits only expanded after the Cuban circuit was racially integrated in the first decade of the new century. One result of an obvious intertwining of sports and politics during the 1906-1909 American occupation was the so-called “American Season,” which was not only played out against the backdrop of deep-seated local resentment of the new overlords – and the burgeoning nationalistic passions that this fostered – but also helped put the new Havana-based winter circuit on strong financial footing for the first time in its initial quarter-century of hardscrabble existence.

The American Season was a string of fall exhibitions between Cuban leaguers and visiting North Americans (big leaguers and Negro leaguers alike) played annually on the eve of the regularly scheduled winter circuit in Havana.3 It held immense social and political meaning for the Cuban fans and press, implications stretching well beyond the athletic field. If the Cubans had earlier used baseball to brand their culture as distinct from that of their Spanish occupiers at the end of the colonial era, they were now also using it to demonstrate perceived equality with (if not superiority over) their new unwelcomed political occupiers from up north. Thus victories in these exhibitions were far more vital to the hosts than they were to the barnstorming Americans, vacationers in truth who came mostly in search of tropical sun and thriving Havana nightlife at the end of a long summer championship season stateside. And these heavily promoted games inevitably spawned native folk heroes on the baseball diamond every bit as big as, or perhaps bigger than, those who a decade or two earlier earned their stripes on military battlefields.

No budding local star benefited more from the circumstances of the newly minted American Season in Havana than did José Méndez. In the near century and a half of island baseball lore, certainly no athlete has been blessed with a better sense of accidental historical timing. The raw, hard-throwing righty had been rather miraculously discovered by longtime island pitching, infield, and outfield star Carlos “Bebe” Royer while toiling in obscurity on a provincial team in his native north coast province of Las Villas (later Matanzas). Handed an unexpected opportunity with the pros back in Havana, the unheralded 20-year-old wasted little time in authoring one of baseball’s greatest debut seasons during the 1908 winter campaign. Méndez virtually burned up the short-season circuit between January and March of 1908, winning nine of his 15 pitching appearances without tasting defeat for an Almendares club that itself played at above .800 baseball (37-8) and waltzed to a second consecutive pennant. While the remarkable rookie was not the club’s lone ace (he started only six times while José Muñoz posted 11 starts and a 13-1 ledger) he grabbed enough attention to earn an additional summer contract with Abel Linares’s Cuban Stars club scheduled to barnstorm in the States. Between mid-July and mid-September the new Cuban ace recorded at least five complete-game shutouts for the Linares-directed Stars, two against the Sol White-managed Philadelphia Giants.4

The story of how Méndez was first discovered by Royer, who at the time was winding down his own two-decade career with the Almendares Blues, is almost the expected stuff of time-tested fiction. Royer was freelancing with future big leaguer Armando Marsans and other Almendares regulars at a Christmastime provincial championship tournament (December 2007) when he spotted “a scrawny black kid playing shortstop” who also threw a mean fastball and snappy curve in spotty relief efforts for a rival Remedios team. Having been earlier assigned the task of checking out a previously touted Remedios hurler who proved far from impressive, Royer quickly urged Almendares skipper Pájaro “Bird” Cabrera to ink the versatile Remedios shortstop instead. Royer’s report was sufficient to cause the Blues manager to grab the 5-foot-9, 150-pound untried prospect from Cárdenas. Méndez, who had reportedly been playing mostly infield for a handful of teams in the north coast region from as early as 1905, was quickly tested in a preseason match with a newly minted Matanzas club about to enter the Havana winter circuit, where he immediately nailed down his roster spot with a reported nifty shutout effort.

If the stellar debut winter season with Almendares signaled a major new star on the horizon, the best was just around the corner for Méndez and the Cuban “American Season” experiment once island action reopened with preseason barnstorming matches between mid-October and mid-December of 1908. The big-league Cincinnati Reds would make the trek to Havana alongside a solid Negro independent team from Brooklyn and would join the Habana and Almendares clubs in two-dozen-plus round-robin games. First on the scene were the Brooklyn Royal Giants, armed with such Blackball stars as Pete Hill, Home Run Johnson, and Bill Monroe. The Royal Giants got off to a rough start, losing a 3-2 thriller to the still-smoldering Méndez; they nonetheless captured seven of their dozen matches with Almendares and the Habana Reds, four against the Blues, including a return matchup with the Almendares ace (a 4-2 loss for Méndez and the Cubans). The true fireworks, however, began more than a month after the early October lidlifter, when the Cincinnati Reds, a fifth-place finisher that summer in the National League, launched a lengthy series of visits by big-league teams that lasted off and on until the eve of the Second World War. This first stopover by a full big-league squad performing under its own banner (and not as a hodgepodge all-star contingent) quickly became the cornerstone of the Méndez legend and the apogee of early Cuban League baseball lore.

Méndez would first amaze the larger baseball world when his opening outing against the National Leaguers not only brought embarrassment to the stunned big leaguers but sent at least minor shockwaves through the white baseball press up north. When the visiting National League club arrived in Havana that winter for their celebrated whirlwind tour, they could hardly have anticipated the rude greeting they would immediately receive from a previously unheralded (at least in the North American mainstream white press) island Blackball strikeout artist. The National Leaguers opened comfortably if not impressively with a 3-1 edging of Habana. But only three days later (November 13) the wheels seemingly came off when Cincinnati’s Jean Dubuc squared off against the Almendares rookie sensation before an overflow afternoon throng in Almendares Park. To the surprise of the visitors, if not the savvy local fandom, Méndez dominated the lethargic Cincinnati lineup and carried a no-hit masterpiece into the ninth frame. Catcher Strike (pronounced “Streaky”) González drove home future big leaguer Armando Marsans (destined himself to pioneer with these same Reds three years hence) in the first inning, and the lone tally stood until the final tense frame. Future Yankees Hall of Fame manager Miller Huggins would finally end the magic with a slow-roller infield hit that died between the mound and second. But with his one-hit brilliance and initial victory, Méndez had launched a shutout string that quickly spread to historic proportions. The Cincinnati club for their part would bounce back in a rematch with Habana two days later, but then saw their bats again fall silent against masterful Almendares pitching, this time falling 2-1 to Andrés Ortega.

After still another embarrassing loss, this time a 9-1 thumping by the Royal Giants, Cincinnati finally seemingly awoke with a lopsided 11-4 shellacking of their Havana namesakes. Then on November 29 Cuban pride was again kindled by Méndez who reprised his outing of two weeks earlier, this time with seven additional spotless innings in relief of starter Bebe Royer in a tight 3-2 loss to the big leaguers. With the scoreless string already at 16 frames, on December 3 magical Méndez again took the hill against Dubuc and once more spun shutout ball in a 3-0 five-hit whitewash. Easily the most memorable feature of the Cincinnati club’s landmark tour of Havana would remain the remarkable performance of the previously unheralded Méndez, who over the final two weeks of November and the first week of December had hurled 25 consecutive shutout innings at the embarrassed National League club.

If Cuba’s “Black Diamond” (El Diamante Negro) became an instant local folk hero by so efficiently taming white big-league bats, and in the process proving that native islanders could hold their own against the best the American overlords could offer, he was only lighting the first flames of a smoldering legend soon destined to spread like wildfire. Within two weeks of handcuffing visiting big leaguers, Méndez again mesmerized a barnstorming club of Americans, white minor leaguers representing Key West – this time by a 4-0 count. The same clubs also met for a three-game renewal with the Almendares team next sailing up to Key West for the rematch. The encore games would provide only more of the same when in the opener Méndez didn’t allow even a single base hit, let alone any runs to mar still yet another superb outing.5 The string would finally be snapped at 45 shutout innings when the Habana Reds eventually broke through in the third frame, during the opening game of 1908-09 regular-season Cuban League action.

The Cuban magic that Méndez launched against the shell-shocked Cincinnati ballclub in late 1908 continued against four additional big-league visitors over the course of the next three winters. Things started a bit roughly for the celebrated Cuban ace the following November when the touring Detroit Tigers (sans front-line stars Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford) administered a 9-3 drubbing in which Méndez went all the way despite surrendering 11 safeties and walking five while striking out seven. Returning to form 10 days later in a rematch with Tigers ace Ed Willett (21-10 that previous summer in the American League), Méndez fell again, 4-0, despite yielding just six hits and one earned run while enduring four costly fielding errors committed behind him. But Méndez did manage a single victory against the Tigers in 1909, a 2-1 five-hitter in his third and final outing. The biggest news of the 1909 series against Detroit, however, transpired when Méndez was actually upstaged by one of his countrymen during a November 18 clash that inspired Cuban pride every bit as much as the earlier Méndez heroics against Cincinnati. The grandest embarrassment yet for the American pros came when a second swarthy Cuban ace, Eustaquio “Bombín” Pedroso, dazzled the Tigers with a brilliant no-hit effort that stretched to 11 innings after an errant throw by second baseman Armando Cabañas allowed an unearned late-game tally. Pedroso – with only two rather ordinary league seasons under his belt at the time, but eventually the owner of a solid 65-46 career mark over a decade and a half – earned his moment of immortality when the same Cabañas executed a perfect squeeze bunt to clinch the victory. Reports indicate that Pedroso at least for the moment became a grander island hero than teammate Méndez and earned $300 in postgame tips when a hat was passed among delirious grandstand supporters.6

If Pedroso briefly occupied center stage during that second American Season of clashes with the big leaguers, it was still destined to be Méndez who remained in the spotlight over the long haul. Legendary manager John McGraw would bring his talented New York Giants to the island for the popular fall series of 1911 (which also included the Philadelphia Phillies) and soon defeated the Cuban ace in all three of his starts (two of them against Christy Mathewson). But reportedly McGraw was nonetheless sufficiently impressed to bemoan the fact that Méndez with his jet-black skin remained off-limits for his own National League roster.7 It was Dolf Luque, however, who somewhat later offered perhaps the highest praise for the talents of the remarkable José Méndez. Returning to Havana for a public celebration honoring his own 27-win 1923 National League campaign, the successful big leaguer is rumored to have spied Méndez lurking in the grandstand and to have approached the aging 36-year-old Negro league star with a most memorable greeting. “This parade should have been for you,” a surprisingly humble and politic Luque allegedly remarked. “Certainly you’re a far better pitcher than I am.”8

The bulk of “The Black Diamond’s” heroic stature – most certainly in his homeland – would forever be based on the handful of stellar outings spread across the first four fall campaigns (1908-1911) featuring visiting big-league squads. Over that brief stretch the skinny kid from Matanzas faced five big-league clubs in 19 games (including one against an all-star lineup cobbled together at the end of the 1909 tour) and won a total of eight decisions while dropping an equal number and tying one. He did impressively master the Reds that very first summer but quickly proved a break-even pitcher. He was 1-4 against the Tigers (first without and later with Cobb and Crawford); he never defeated McGraw’s Giants (0-3) although he did enjoy a single success on December 14, 1911, when he earned what would later be called a “save” with four final shutout innings during the only Almendares victory over Mathewson. It was an impressive enough string to suggest the Cuban’s stature as a potential big leaguer. But in the end how much should be made of all this, even if we excuse the shortness of the run and assume that such exhibitions are by any measure the true equivalent of actual championship big-league games?

Most if not all historians have chosen to dwell on the highlights over the full record.9 As the years spread on, Méndez obviously lost some of his mastery. He began dropping more decisions than he won, a fact rarely noted in the laudatory accounts penned by Holway and other Blackball apologists. In the end, his two dozen appearances against big leaguers over a half-dozen American Seasons resulted in a losing ledger. Of the nine wins, only three (against seven setbacks) came after 1910. Even including the three more successful years (1908-1910), in seven of his 24 outings he yielded more than 10 hits. If games against minor leaguers and semipros (including an impressive 1913 no-hit effort against a Birmingham Southern Association club) are added in, the complete record (24-22) edges a notch above .500 but hardly seems to reflect Cooperstown immortality.

Of course it was not the American Seasons and their symbolic exhibitions alone that provided so much fodder for growing Cuban pride. Official winter seasons in Havana at the height of the American occupation also played a similar role. The first important forge in the link of the Cuban League and the Negro leagues would come with the 1907 and 1908 seasons when US Negro leaguers first showed up on Cuban League playing rosters. Against the backdrop of an unwelcome North American puppet administration, the importing of black stars from up north worked in a backhanded way to stimulate a good deal of patriotism among Havana fans, and it was nationality and not race that was the issue here. The 1907 season saw an all-Cuban Almendares team capture a league title over a Fé club stocked mostly with African-American imports from the Philadelphia Giants – Preston Hill, Rube Foster, Home Run Johnson, Charlie Grant, and Bill Monroe among them. It was a tight race throughout with Almendares, paced by future big leaguers Armando Marsans and Rafael Almeida, managing to pull out the pennant-clinching victory on the final day of the season before an enthusiastic overflowing crowd jamming Almendares Park. The following winter season Almendares proved even more dominant, largely thanks to the debut appearance of Méndez, who as a 20-year-old phenomenon (9-0) quickly proved a league ace – along with teammate Joséito Muñoz (equally dominant at 13-1). The all-native champions outpaced the Habana Reds (featuring Americans Preston Hill, Clarence Winston, Bill Monroe, Grant Johnson, and ace Rube Foster) by five full games.

It is true enough that Méndez did amass a substantial record of achievement during the first decade and a half of the twentieth-century Cuban winter circuit. Beating American big leaguers in Havana thrust Méndez into the national and even international spotlight, but his numerous victories in 1908 and 1909 over rival Cuban League clubs Habana and Fé – teams primarily staffed with imported American Negro leaguers – worked just as heavily to cement his immediate national icon status. Performances in the American Seasons were thus certainly matched if never quite altogether overshadowed (especially for the contemporary stateside white sporting press and later-era champions among late twentieth-century Blackball historians) by a string of equally noteworthy Cuban League outings. For his first four years in the league, Méndez truly dominated rival hitters, including some of the era’s best imported Negro leaguers like Clarence Winston, Preston Hill, George Johnson, and Bruce Petway. That stretch featured 42 victories against but eight defeats, plus 43 complete games. Three seasons (1908, 1910, 1911) he won league pennants for Almendares almost single-handedly, posting more than half his team’s victories (such as in 1910, when his unblemished 7-0 ledger paced the Almendares club that finished first with but 13 victories in a truncated 16-game schedule). And like most Cuban stars of the era, he was a versatile ballplayer who could also perform with precision as a shortstop. When a tired arm reduced and even killed mound effectiveness, the infield slot became his main responsibility in later years with the Kansas City Monarchs. He was originally discovered while manning that post, and visiting big leaguer Ira Thomas would later report that “not only is he a phenomenal slab man, he is a most excellent fielder as well and his hitting is hard and timely.”10

Even if the stellar performances against North American barnstorming clubs are erased from memory (or discounted for their questionable legitimacy), Méndez’s achievements in the Cuban winter-league record books are substantial for all the brevity of a career that peaked for five or six early campaigns (between ages 21 and 27), then dragged on with several interruptions (he missed five of six seasons as a pitcher between 1917 and 1923). He owns the all-time mark for winning percentage (76-28, .731) and his three undefeated seasons (1908, 1910, 1913-14) is a distinction never matched. His record for most seasons leading the league in shutouts (both overall and consecutively) was also never matched. And there are a handful of other similar and substantial distinctions – five times leading in winning percentage and an equal number of campaigns as the leader in shutouts. When the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame was established in Havana in 1939, Méndez was a member of the charter class of inductees. But the downside was that a highly noteworthy career in Havana that stretched out across almost two decades was more or less over – at least on the pitcher’s mound – after only nine short winter seasons. And therein lies part of the rub.

The North American Negro League career enjoyed by Méndez also has its strong if often thinly documented boasting points. By the time Rube Foster’s Negro National League debuted as an organized circuit in 1920, a mostly dead arm had largely snuffed out further pitching glory for the Cuban ace. He signed on with J.L. Wilkinson’s Kansas City Monarchs for the debut season of the NNL as playing manager, and although the bulk of his playing time came in the middle infield, he nevertheless displayed leadership qualities that guided his team to three consecutive pennants (1923-1925). He also at least in part rehabilitated his pitching career as his arm troubles slowly dissipated, but got by more on veteran craftiness than former speed and logged a far reduced load of mound appearances and innings. His best mound record on the summer circuit came in 1923 (15-5, with a league best 1.89 ERA) and he also claimed nine of 10 decisions over the next three seasons in more limited hurling duties. But as a North American Negro Leaguer, the Cuban’s prime performances fell during his stellar early years as a barnstormer with the Brooklyn Royal Giants (1908), the Cuban Stars (1909-1912), and Wilkinson’s All-Nations (1912-1917). And after the arm troubles popped up late in 1914 on the heels of his last great winter season with Almendares (when he went 10-0 that year), the remarkable Méndez pitching legend was largely a thing of the past.

Yet by all accounts Méndez performed equally as well as a Negro league hurler on the US summer circuit as he did in winter venues, at least before the nagging arm issues limited his one-time effectiveness. With the Cuban Stars in 1909 he is estimated by numerous sources to have compiled a 44-2 record, one of the best pitching ledgers found anywhere in baseball history.11 He would star in the first-ever modern-era Negro Leagues World Series in 1924, when he recovered some of his pre-injury mound magic, hurled one shutout, and earned still another victory in relief for Wilkinson’s victorious Monarchs. If the statistical record remains thin, Negro League performances have nonetheless spawned rich descriptions of the Cuban’s pitching style among former rivals and latter-day historians. John Holway cites unnamed old-timers as claiming the Cuban threw “a fastball that looked like a pea” and “a curve that looked like it was falling off a pool table” (Blackball Stars, 50). James Riley repeats a probably apocryphal story that Méndez once killed a teammate by hitting him in the chest with a fastball during batting practice (The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, 546). But tragedy was never far away from Méndez’s doorstep and the debilitating arm injury (likely the result of too much hard throwing unsustainable on such a wiry frame) was only a prelude to the ill fate that awaited down the road. When what Holway describes as a “gray, gaunt and grim” 36-year-old Méndez shut down the Hillsdale club of the Eastern Colored League in the deciding 10th contest of the marathon first Colored World Series (October 20, 1924), no one imagined that death was a mere four years away.

One of most remarkable and informative accounts of Méndez was penned in March 1913 by former Philadelphia Athletics catcher Ira Thomas. The praise – part of a lengthy article that appeared in the pages of Baseball Magazine and was the 10-year veteran receiver’s first-hand account of how island baseball had grown by leaps and bounds in recent years – was substantial if perhaps a bit hyperbolic. Thomas opines that “it is not alone my opinion but the opinion of many others who have seen Méndez pitch that he ranks with the best in the game. I do not think he is Walter Johnson’s equal, but he is not far behind. He has terrific speed, great control, and uses excellent judgment.” But there are unfortunately few details here to flesh out the report. And there is also a final note of skepticism when the big leaguer notes that “it seemed to me on my last visit that he had slowed up a little since the first time I had become acquainted with his fast straight ones.”12

Perhaps one element casting Méndez more in the realm of myth and legend than in the universe of flesh-and-blood ballplayer is the true scarcity of biographical detail surrounding the athlete’s pre- and post- ballplaying life. Of his birth we know only the date and location, and the fact (reported by Cuban biographer Severo Nieto) that his parents were José Méndez and Manuela Baez. And we have the reports of Robert González Echevarría (The Pride of Havana) that childhood and young adult interests included music and carpentry as well as baseball playing.

The details of Méndez’s death also are at best quite sketchy. Little is known about his final months and illness, only that he was reported deceased less than 22 months after hurling his final Cuban League victory (on January 26, 1927) and barely two years after his final triumph on the hill for the Kansas City Monarchs (June 13, 1926, over the Cleveland Elite).13 There is even some dispute over the actual date of his death, which is reported in a pair of sources as October 31, 1928 (Nieto and Wikipedia), and in yet another as November 6 (Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball). González Echevarría (The Pride of Havana), who provides one of the fuller portraits of the pitcher’s youth, has surprisingly nothing to say about his demise and at one point even inaccurately gives 1930 as the death date. It is nonetheless clear that Méndez died in obscurity and apparent poverty and that he was most likely the victim of TB – James Riley claims bronchopneumonia without citing any sources. His lone Cuban biographer, Severo Nieto (José Méndez: El Diamante Negro), repeats the October 31 date of demise but gives only two small details: that the pitcher was scheduled for a special award ceremony by Cuban League officials in the autumn of 1928 but was too ill to attend the ceremony, and that his body remained at 22 Picota Street for several days of viewing before interment in the Colon Cemetery. The final resting place is indeed today widely considered to be the Colon Cemetery grounds in the Vedado section of Havana, somewhere within the dual crypts honoring veteran ballplayers (his name is inscribed on one of those dilapidated monuments).14 But there is no individual tombstone and apparently no individual casket for the eventual Hall of Famer.

Early life details are equally incomplete and shadowy. Nieto’s Spanish-language volume is mostly pure hagiography plus endless strings of box scores, and begins with the well-told tale of the raw youngster’s amateur tournament discovery by Royer. The best biographical information, limited nonetheless, is provided by González Echevarría, who offers some insightful notes on the young athlete’s personality and personal life during the earliest years in the village of Cárdenas, the island’s late nineteenth-century hotbed of Afro-Cuban music and religion. Born March 18, 1887 (the only solid fact), the youngster reportedly apprenticed as a carpenter, came from a family of successful artisans, and also displayed talent as a musician early in life (he mastered the guitar and clarinet), and González Echevarría therefore places the future athlete squarely within an Afro-Cuban musical culture that reigned on the island in the earliest years of evolving nationhood.15 There are no details about parents, siblings, or formal education in the González Echevarría account beyond the mentioned musical predilections. A single biographical detail is that he was early nicknamed “El Cardenense” (Man from Cárdenas) when he burst on the Havana baseball scene in early 1908, and also less admirably called “Congo” (or “Congolese” – a popular if now seemingly tasteless reference to his jet-black skin color). On the heels of his patriotism-stirring 1908 and 1909 triumphs over the visiting Americans, the less tasteful moniker was rather quickly transformed into the more celebratory “El Diamante Negro” (The Black Diamond), which became his lasting and more reverential epithet.

González Echevarría draws even closer ties between the future pitcher and religion than those attached to the Matanzas region’s musical heritage. His known complete birth name of José de la Caridad Méndez Arco de Tejada was apparently given by presumably pious parents to brand him as a perfect emblem of the cultural unity that marked much of the Spanish-controlled but African-infused nineteenth-century Cuban colony. “De la Caridad” indicated someone entrusted at birth to the Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre, the island’s patron saint. That original Catholic icon had been adopted and transformed by the island’s original slave populations into the Yoruba deity Ochún. In the words of González Echevarría, “Méndez was the very embodiment [through his name, skin tone, and Yoruba cultural heritage] of the Cuban nation as represented by the ideals that led Cubans to fight for independence during his childhood.”16

The Special Negro Leagues Committee Cooperstown election of 2006 was likely long overdue and can be justified as a needed antidote to the sport’s unforgivable racist past. But quick fixes are often prone to flaws in execution. From one viewpoint the election of Méndez and fellow Cuban Blackball nonpareil Cristóbal Torriente (plus the likes of Negro League heroes such as Pete Hill, Biz Mackey, and Ray Brown) and can be taken as a clearcut triumph for those who wish to set the record straight on one of the darker corners of baseball history. But on the other hand, a certain amount of controversy inevitably has to remain.

The argument against Méndez as a legitimate Cooperstown Hall of Famer is complex but also somewhat obvious on the surface. Open to question are both the length of his career (not the total years but the years of legendary achievement) and the shifting level of the competition against which he built the bulk of his reputation. Great single games (in this case perhaps a half-dozen of them against legitimate big leaguers) or even unmatched single-season performances are not an automatic pass to Cooperstown. If so, then where is Roger Maris? Or Orel Hershiser and Fernando Valenzuela? If brief comets – or even longer-tenured heroes with a few aberrant rises into the most brilliant sunshine – were the key to true immorality, then Cooperstown would also surely have spaces for Don Larsen, Dusty Rhodes, Herb Score, and even Brady Anderson. It is for a transparent reason that Cooperstown eligibility is based on a minimum 10 years in the big time. And all of the above-mentioned group earned their fame on a stage where there could be no debate about the quality of talent or the legitimacy of the games in which they played. No one today argues for Omar Linares to receive a Cooperstown pass (despite a Cobb-like .368 Cuban League career batting mark built over 20 seasons), although the island league Linares dominated for so long was arguably of far higher caliber than the three- and four-team short-season turn-of-the-century winter circuit that was home for Méndez. Sadaharu Oh has no home in big-league baseball’s Valhalla because of the questions about the quality of Japanese pitching against which Oh outdistanced Hank Aaron and Barry Bonds.

Cuba’s “Black Diamond” remains one of the largest oversized diamond legends from an island nation packed with an unmatched baseball legacy. But it is also the twin curse of his sketchily documented career that he would be destined to suffer as well a hefty negativity attached to both his legend and his seemingly indelible myth. He was designed to be touted almost exclusively for a handful of brilliant outings that island political history (at the time they were performed) and later post-integration political correctness (a century after his triumphs) morphed into something perhaps more than the record justifies. For three brief winter seasons he outmatched visiting big leaguers who may or may not have been playing to their full potential. During four additional monthlong American Seasons in Havana, he at least held his own against the likes of Christy Mathewson, Chief Bender, and Eddie Plank, even if some of the luster was suddenly gone. But are fall exhibitions a true calling card to Cooperstown? Did he shine long enough even in his domestic Cuban winter circuit (whatever one makes of its reputation or stature) to be considered a legitimate Hall of Famer?17 These are of course the questions and debates that enliven the sport of baseball and fire the best of annual “hot stove league” discussions. The sport’s true appeal has always been far more its myths that any of its true factual legacy.

Jose Méndez “American Season” Record versus Major Leaguers (1908-1913)

Date – Opponent, Result, Innings Pitched, Runs, Hits – MLB Pitcher (Big-League Record)

1908 record, 2 W – 0 L

- November 13, 1908 – Cincinnati Reds, 1-0 (W), 9.0 IP, 0 R, 1 H – Jean Dubuc (5-6)

- November 29, 1908 – Cincinnati Reds, 2-3 (ND), 7.0 IP, 0 R, 2 H – Billy Campbell (12-13)

- December 3, 1908 – Cincinnati Reds, 3-0 (W), 9.0 IP, 0 R, 5 H – Jean Dubuc (5-6)

1909 record, 2 W – 2 L

- November 4, 1909 – Detroit Tigers, 3-9 (L), 9.0 IP, 9 R, 11 H – Ed Willett (21-10)

- November 14, 1909 – Detroit Tigers, 0-4 (L), 9.0 IP, 4 R, 5 H – George Mullin (29-8)

- November 22, 1909 – Detroit Tigers, 2-1 (W), 9.0 IP, 1 R, 5 H – Bill Lelivelt (0-1)

- December 16, 1909 – Big League All-Stars, 3-1 (W), 9.0 IP, 1 R, 2 H – Howie Camnitz (25-6)

1910 record, 2 W – 2 L

- November 13, 1910 – Detroit Tigers, 0-3 (L), 9.0 IP, 3 R, 5 H – George Mullin (21-12)

- November 21, 1910 – Detroit Tigers, 2-2 (ND), 10.0 IP, 2 R, 3 H – Ed Summers (13-12)

- December 5, 1910 – Detroit Tigers, 3-6 (L), 9.0 IP, 6 R, 13 H – Ed Summers (13-12)

- December 13, 1910 – Philadelphia Athletics, 5-2 (W), 9.0 IP, 2 R, 5 H – Eddie Plank (16-10)

- December 18, 1910 – Philadelphia Athletics, 7-5 (W), 9.0 IP, 5 R, 9 H – Eddie Plank (16-10)

1911 record, 2 W – 4 L

- November 5, 1911 – Philadelphia Phillies, 3-1 (W), 9.0 IP, 1 R, 5 H – George Chalmers (13-10)

- November 13, 1911 – Philadelphia Phillies, 4-0 (W), 9.0 IP, 0 R, 4 H – Eddie Stack (5-5)

- November 19, 1911 – Philadelphia Phillies, 1-8 (L), 8.0 IP, 8 R, 13 H – George Chalmers (13-10)

- November 30, 1911 – New York Giants, 0-4 (L), 9.0 IP, 4 R, 5 H – Christy Mathewson (26-13)

- December 10, 1911 – New York Giants, 3-6 (L), 11.0 IP, 6 R, 11 H – Doc Crandall (15-5)

- December 14, 1911 – New York Giants, 7-4 (Save), 4.0 IP, 0 R, 1 H – Christy Mathewson (26-13)

- December 18, 1911 – New York Giants, 1-4 (L), 8.0 IP, 3 R, 5 H – Christy Mathewson (26-13)

1912 record, 1 W – 2 L

- November 3, 1912 – Philadelphia Athletics, 3-6 (L), 9.0 IP, 6 R, 10 H – Chief Bender (13-8)

- November 11, 1912 – Philadelphia Athletics, 4-7 (L), 8.0 IP, 7 R, 12 H – Eddie Plank (26-6)

- November 17, 1912 – Philadelphia Athletics, 3-6 (ND), 5.0 IP, 0 R, 2 H – Chief Bender (13-8)

- November 25, 1912 – Philadelphia Athletics, 3-2 (W), 8.0 IP, 2 R, 6 H – Chief Bender (13-8)

1913 record, 0 W – 1 L

- November 8, 1913 – Brooklyn, 0-4 (L), 9.0 IP, 4 R, 10 H – Bull Wagner (4-2)

Totals: 9 W – 11 L, 204.0 IP, 74 R, 150 H (*at least 28 ERs but the figure is incomplete)

This summary of the Méndez American Season record was originally compiled by SABR researcher Gary Ashwill from box scores in the contemporary Cuban press. Some apparent errors in dates of games in the original Ashwell compilation have been corrected here. Since data on earned runs was spotty, Ashwill calculated a 3.26 total run average across the 204 accountable innings that Méndez worked. Severo Nieto (José Mendez: El Diamante Negro, 186) provides a more detailed chart including American Season contests Méndez pitched against not only big leaguers but also visiting minor-league and Negro League clubs. That listing extends through 1915, includes 52 games (35 complete games), a 24-22 overall won-lost mark, and a 2.77 total run average.

Sources

Alfonso, Jorge. “La Leyenda del Diamante Negro,” in Bohemia 93:2 (2001): 17-18. Havana, Cuba.

____________. “Méndez, La Principal Atracción,” in El Deporte (March 6, 1988): 81-85. Havana, Cuba.

Bjarkman, Peter C. A History of Cuban Baseball, 1864-2006 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2007).

Figueredo, Jorge S. Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2003).

____________. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2003).

González Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana – A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Holway, John B. “Jose Mendez: Cuba’s Black Diamond” (Chapter 4, 50-60) in Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988).

José Méndez file at National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York.

Nieto Fernández, Severo. José Méndez, El Diamante Negro (Havana: Editorial Científico-Técnica, 2004).

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994).

Rucker, Mark, and Peter C. Bjarkman. Smoke: The Romance and Lore of Cuban Baseball (New York: Total Sports Illustrated, 1999).

Skinner, David. “Havana and Key West: José Méndez and the Great Scoreless Streak of 1908,” in The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History, Volume 24 (2004): 17-23. Society for American Baseball Research.

Thomas, Ira. “How They Play Our National Game in Cuba,” in Baseball Magazine, March 1913: 61-65.

Notes

1 The case for and against the Cooperstown enshrinement of Torriente is taken up in a separate biography devoted to the slugging outfielder.

2 The enshrinement of Méndez and Torriente also has to raise the issue of Adolfo Luque, the acknowledged sole true Latin American big-league star before 1947 integration, a winner of nearly 200 major-league contests, the first Latin hurler to claim 100 victories, appear in a World Series, lead one of the big-league circuits in victories and ERA (with Cincinnati in 1923), and still holder of the Cincinnati franchise record for single-season victories. Of course Luque never had the benefit of a Negro Leagues lobby or a special election like the one in 2006; although light-skinned enough to reach the majors, he suffered a different kind of racial discrimination – the prejudicial attitudes toward early Spanish-speaking stars who were typically discounted as nothing more than “hot-blooded Latinos” and whose occasional displays of on-field frustration all too easily eradicated their considerable achievements. Luque’s underappreciated career is also treated here in a separate chapter.

3 The American Series was launched on a small scale in 1903 with the visit of the first American all-black team, paradoxically named the Cuban X-Giants although there were no islanders on the roster. In a nine-game series against local clubs (none from that year’s pro winter circuit), the Americans won only once and tied a third contest. The series burgeoned the followed fall with five different teams from up north (including the Cuban X-Giants and a group of big-leaguers known as the All-Americans) and the winter-league champion Habana Reds among the squads taking part.

4 Severo Nieto Fernández, José Méndez, El Diamante Negro, 8.

5 The games in Key West were truly historic since they represented the first integrated matches in that city. Figueredo (Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 77) reports that Almendares infielder Armando Cabañas was barred from entering US territory for the rematch series not because he was a Negro but because immigration authority thought he might be Chinese. The initial two games were peaceful but in the third, bottles and stones were hurled at the Cubans and even the local mayor entered the playing field to harass Almendares pitcher Joseito Muñoz.

6 Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 82. Figueredo reports that among the contributors were both a sitting and a future Cuban president, and also rival ballplayers George Mullin and Charles O’Leary of the vanquished Tigers.

7 Holway (Blackball Stars, 56) cites contemporary press reports and later McGraw biographies in reporting that Mrs. John McGraw referred to Méndez as “the black Mathewson” and explained that her husband frequently bemoaned the fact that at the time he didn’t have courage to abandon customs underpinning the “Gentleman’s Agreement” and recruit players like Méndez or Bombín Pedroso on pitching abilities alone.

8 The involvement of Luque here adds a welcomed touch to the legend. But the tale is most likely apocryphal. The source for the incident and quotation is again John Holway (Blackball Stars, 59). But like the bulk of Holway’s work, which is always heavy on hagiography and legend-spinning but usually rare on careful scholarship, there is no source cited for the incident of the suspicious quotation. It is noteworthy that while González Echevarría devotes several full pages to the several ceremonies honoring Luque in Havana during the summer of 1923 (The Pride of Havana, 173-175), there is never any mention of the presence of Méndez.

9 This summary of the Méndez American Season record was originally compiled by SABR researcher Gary Ashwill from box scores in the contemporary Cuban press. Some apparent errors in dates of games in the original Ashwell compilation have been corrected here. Since data on earned runs was spotty, Ashwill calculated a 3.26 total run average across the 204 accountable innings that Méndez worked. Severo Nieto (José Mendez: El Diamante Negro, 186) provides a more detailed chart including American Season contests Méndez pitched against not only big leaguers but also visiting minor-league and Negro League clubs. That listing extends through 1915, includes 52 games (35 complete games), a 24-22 overall won-lost mark, and a 2.77 total run average.

10 Ira Thomas, “How They Play Our National Game in Cuba,” 62.

11 Both Riley and Severo Nieto cite this reported 1909 ledger but neither offer details. Severo Nieto (in a footnote) credits the won-lost total as coming from unpublished research by SABR member Merl Kleinknecht.

12 Thomas is referring here to the Philadelphia club’s recent November 1912 Havana junket in which Méndez won a single contest while dropping two and getting no decision in the fourth. He remarks that years of service seem to be taking a toll on the still only 25-year-old hurler and offers a further explanation when he suggests that the Cuban “with all his terrific speed, has not what would seem a good build for such a wearing delivery. He is rather slight, does not appear muscular enough to stand such a strenuous pace. But he can still pitch with the best.” Thomas further offers the familiar appraisal of the era that “if he were a white man he would command a good position on a major league club in the circuits.” The bottom line is that one veteran big leaguer is here sanctioning Méndez as a legitimate professional prospect but certainly not suggesting he might merit a slot among the greatest of the age like Johnson, Mathewson, or perhaps his own teammates Eddie Plank and Chief Bender. And this valued assessment comes from an experienced receiver used to handling some of the best hurlers on the big league circuit.

13 The date of a final Cuban League win has in some sources been erroneously reported as January 21 (Wikipedia’s online Méndez entry for example), but his last league complete-game victory was a 12-5 Alacranes win over Marianao on January 26 (a contest miraculously played in 1 hour and 50 minutes despite the 17 runs scored). Cuba celebrated a pair of winter championships in 1926-27, and it was in the second, known as the Triangular Championship, that Méndez last performed with a version of the Almendares club redubbed as the Alacranes (Scorpions). His final victory in relief would come three days after his final complete game as a starter; it was a 10-9 10-inning triumph over the Habana Red Sox in which he relieved starter Oscar Tuero. Box scores for these (and many other Méndez games) are provided in the Severo Nieto biography (José Méndez: El Diamante Negro)..

14 There are two such ballplayer monuments in the Colon Cemetery, erected by the Association of Christian Ballplayers in 1941 and 1952 and now crumbling due to lack of maintenance and repair. If the Méndez remains now reside there, it is not clear where on the grounds they were entombed for the first dozen years after his death.

15 González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, 129-130.

16 González Echevarría, 130. Extending the significance of the ballplayer’s full name, González Echevarría elaborates that the Catholic deity in her original form was traditionally represented as a richly adorned mulatto to whom three storm-tossed men in a boat prayed desperately for their lives. The three sailors were a white, a black, and an Indian, the three ethnic components of the Cuban nationality.

17 Méndez’s spot in the inaugural 1939 class of the original Havana-based Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame (defunct after the Castro revolution), remains fully justified, given the importance of his victories over the American visitors at the very time Cuba was struggling to shape a national identity. Those wins, for Cubans at least, were the stuff of nation-building and not merely the stuff of dusty sporting archives.

Full Name

José de la Caridad Méndez

Born

March 19, 1887 at Cardenas, Matanzas (Cuba)

Died

October 31, 1928 at Havana, (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.