September 10-13, 1883: Grasshopper Jim Whitney snatches the pennant

In September 1883 a key late-season series in Boston pitted perennial powerhouse Chicago against a fine nine from Beantown. The Windy City team blew into the Hub holding first place, riding an 11-game win streak and appearing destined for a fourth consecutive National League title. Boston, however, was knocking on the door, a game and a half out, despite having just dropped two of three to the Providence Grays. And the Beaneaters would see to it that their visitors left town with pennant hopes dashed, thanks to a man called Grasshopper.

Chicago’s White Stockings fairly owned the League in the 1880s: five pennants and only one finish out of the top three. Led by future Hall of Famers Cap Anson and King Kelly, they fielded a lineup that was a veritable all-star team unto itself. Pitching duties were shared by Fred Goldsmith, a steady 20-game winner, and Larry Corcoran, who topped 30 victories four times between 1880 and 1884.

Chicago’s White Stockings fairly owned the League in the 1880s: five pennants and only one finish out of the top three. Led by future Hall of Famers Cap Anson and King Kelly, they fielded a lineup that was a veritable all-star team unto itself. Pitching duties were shared by Fred Goldsmith, a steady 20-game winner, and Larry Corcoran, who topped 30 victories four times between 1880 and 1884.

Boston could not boast the stable of stars that Chicago did, but the Beaneaters were not without stalwart veterans and promising youngsters. Jack Burdock and Ezra Sutton held down infield positions as they had since playing on Boston’s 1878 pennant winners, and first baseman-manager John Morrill had done service with the team since the inaugural 1876 season; all three were batting over .300. Twenty-two-year-old pitcher Charlie Buffinton was on his way to a 25-win season … but he was not the ace of the staff.

James Evans Whitney had broken in with Boston in 1881, making an immediate splash by leading the National League in both games won (31) and games lost (33) for a team that struggled to end up at 38–45. Possessor of a nickname alternately attributed to the shape of his head1 and to the way he walked,2 Grasshopper Jim lasted 10 seasons in the majors, piling up 191 wins along the way. The 6-foot-2, 170-pound workhorse would clock 514 innings and 54 complete games in 1883, and set an NL record for strikeouts with 345. His greatest strength was his control of the strike zone: ’83 was the first of three consecutive years he topped all pitchers in strikeout-to-walk ratio.

An audience of close to 3,500 packed Boston’s South End Grounds on Monday, September 10, for the series opener. “The interest manifested in the critical situation of the struggle for the league championship was well shown by the large attendance at the base ball grounds,” the Boston Daily Advertiser reported.3 Morrill’s club, despite committing an embarassing seven errors, evaded disaster thanks to its big right-hander. As the Advertiser concluded: “Whitney was the obstacle that (Chicago) could not surmount, and the bats would whistle around that sphere in every exasperating way but the right way.”4 Whitney’s line for the 4–2 complete game win: nine strikeouts, three hits, one walk, no earned runs. Goldsmith took the loss.

Now a half-game back of the visitors, Boston sent Whitney to the box again Tuesday, this time to face Corcoran. Cap’s men cobbled together a two-run sixth but failed to hold the lead. Boston scored the tying and winning runs in its final at-bat, and Whitney closed with a one-two-three ninth. The nearly 4,000 spectators went home happy; their Beaneaters were now in possession of first place.

On Wednesday the 12th, Whitney patrolled center field, as he usually did when he wasn’t pitching, and it was Buffinton’s turn to corral Anson’s troops. About 2,900 fans stuck around despite a persistent drizzle, and they were rewarded with an 11–2 Boston rout. Goldsmith suffered his second defeat of the series.

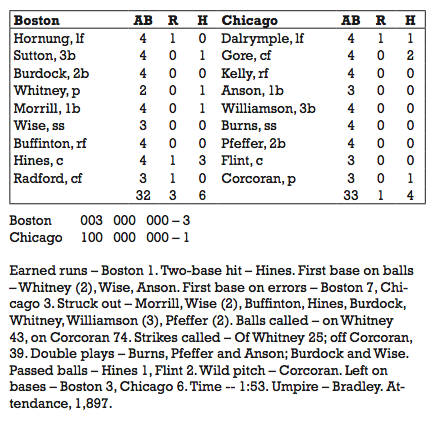

Thus the stage was set for the finale on Thursday the 13th. Even with a victory, the White Stockings could not reclaim first place, but they could claw back to within a half-game of the lead and send a message to the Bostonians that they were not entirely down and out, despite a poor three days’ showing. The smallest crowd of the four-game set, a handful under 2,000, was attributable to unfavorable conditions. “The weather was rainy and the ground soft,” noted the Chicago Daily Tribune.5

For the White Stockings, Abner Dalrymple’s leadoff drive to left in the first was misplayed by left fielder Joe Hornung, landing Abner on second base. Up next came George Gore, who pushed the runner to third with a single, whence he was brought home by Kelly’s fly ball. They threatened again two innings later, but with men on second and third with no outs, Hornung and center fielder Paul Radford made fine plays to hold them at bay. Hornung came through again in the fifth, running down a “terrific drive”6 over his head off Corcoran’s bat with a man on.

Boston got all the runs Whitney needed in the third. Catcher Mike Hines, who went 3-for-4 in the game, opened with a double. Radford and Hornung reached via infield errors. With Hines already home, Sutton stepped in next and laced a two-run single. Thus ended the day’s scoring. Corcoran was no easy touch; more Bostons made first on errors (seven) than on hits (six). He allowed but one earned run.

The problem for the Windy City men was that Whitney was even better. The four base hits he allowed were scattered and thus largely harmless. His strike-zone mastery was in evidence, as he struck out four while surrendering just a single base on balls. With Chicago mounting a last-gasp challenge in the ninth, fueled by a Buffinton muff and a questionable safe call by the umpire,7 Whitney fanned Fred Pfeffer to end the affair and notch his 32nd victory.

Hurling three complete games, Whitney had yielded a modest 13 hits, which in turn produced but two earned runs. Only two batters were able to milk him for walks, while 19 went down on strikes. Anson, Kelly, Gore, Pfeffer, and Ed Williamson together mustered a scant three safeties. After the series ended the Beaneaters won nine of their final ten to win the title, but the true turning point came in that series against Chicago, when Grasshopper Jim Whitney held sway over the 19th-century version of Murderers’ Row.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 Lewis, Jeff. “Nicknames Colorful in Sports Arena, “ Rockmart Journal (Georgia), September 10, 1986, p. 2B; entry for “Whitney, James Evans” in Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 1, ed. David Nemec (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), p.198.

2 Ivor-Campbell, Fred. Entry for “Whitney, James Evans” in Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: 1992-1995 Supplement (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995), p. 226.

3 Boston Daily Advertiser, September 11, 1883, p. 8.

4 Boston Daily Advertiser, September 11, 1883, p. 8.

5 Chicago Daily Tribune, Sept. 14, 1883, p. 2.

6 Boston Daily Advertiser, Sept. 14, 1883, p. 9.

7 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Boston Beaneaters 6

Chicago White Stockings 1

South End Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.