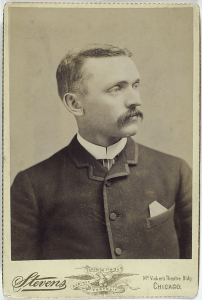

Abner Dalrymple

“Steady as a clock,”1 Abner Dalrymple was a fixture in left field for the 1880s Chicago White Stockings, a powerhouse that won five National League pennants over seven years. Together with Mike “King” Kelly and George Gore, he formed what manager Adrian “Cap” Anson called “the greatest trio of outfielders ever gotten together in one club.”2 Gaffes in Game Six of the 1886 World Series cast Dalrymple as the first goat in fall classic history and marked the end of his time in the Windy City.

“Steady as a clock,”1 Abner Dalrymple was a fixture in left field for the 1880s Chicago White Stockings, a powerhouse that won five National League pennants over seven years. Together with Mike “King” Kelly and George Gore, he formed what manager Adrian “Cap” Anson called “the greatest trio of outfielders ever gotten together in one club.”2 Gaffes in Game Six of the 1886 World Series cast Dalrymple as the first goat in fall classic history and marked the end of his time in the Windy City.

A career .288 left-handed line-drive hitter, Dalrymple accumulated more than 1,200 hits over a 12-year major-league career that included stops in Pittsburgh and Milwaukee. Along the way he earned a batting title as a rookie that he later lost, a home run crown, and a single-game record for doubles that remains unbroken. In his prime, Dalrymple was listed as standing 5-foot-10½ and weighing 175 pounds.3

Playing much of his career in an era when batters specified pitch location, Dalrymple’s bat control awed Hall of Fame catcher Buck Ewing. “Talk about [Napoleon] Lajoie and others who can hit any kind of ball, old Abner Dalrymple was about as good as anybody I ever saw,” said Ewing, adding “he could make more off of poor balls than any of them.”4

In addition to bat skills, Dalrymple was also blessed with speed and a right arm good enough to average a dozen outfield assists a year. That skill set led sabermetrician Bill James to rank Dalrymple tenth among 19th-century left fielders.5

Gentlemanly in manner and temperate with alcohol,6 Dal, as he was called, was a fan favorite. At former stomping grounds he was routinely showered with gifts from adoring fans. But as Dalrymple’s career wound down, a less honorable side emerged. While playing for a Denver team, he racked up so many unpaid debts he asked for his release to escape local creditors. His refusal to repay a loan resulted in a sheriff’s deputy seizing gate receipts from what proved to be his final major-league game. Soon after, Dalrymple abandoned his wife to live with another woman 2,000 miles away. The couple reconciled, after which Dalrymple straightened out his life and enjoyed a lengthy second career as a railroader.

Abner Frank Dalrymple was born in September 1857 to Samuel and Harriet Dalrymple, in the southwest Wisconsin village of Gratiot. Present-day databases, dating back to at least 1951, list September 9 as Dalrymple’s date of birth, but a State of Illinois index of deaths, and an obituary published by a local newspaper from a town nearby where he lived late in life, reported that he entered the world on September 19.7

By 1870 the Dalrymple family, which included an older sister to Abner plus two younger sisters, lived across the Illinois state line, in the town of Warren. That year’s US census identified Samuel as an auctioneer born in New York and Harriet as a housekeeper born in Ohio.

At the age of 14 Dalrymple was playing for a team of Illinois Central Railroad engineers. To qualify for the team, he took a job as a brakeman. Two years later he formed a team that earned $300 (over $8,000 in 2023 dollars) by winning a tournament at the Freeport, Illinois, fair.8 By 1876 Dalrymple was playing for the Freeport Base Ball Club. The team’s number nine hitter and third baseman, he helped turn “a fine tripple [sic] play” in mid-July then did it twice more three days later.9 By season’s end Dalrymple was batting cleanup for the undefeated Red Stockings.

The following spring Dalrymple was a center fielder for the Milwaukee nine of the League Alliance. Hitless in his professional debut, he led the third-place Cream Citys in batting average, runs scored and hits.10 Moved to left field, Dalrymple’s fielding drew superlatives: “immense” in one game, and “magnificent” in a no-hitter tossed by Sam Weaver.11

The most important at-bat of Dalrymple’s season may have come in an exhibition game loss to the defending NL champion Chicago White Stockings on July 12. In the eighth inning Dalrymple broke up a no-hitter by Al Spalding,12 the man who would later lure him to Chicago.

Milwaukee’s third-place finish earned them entrance into the National League for the 1878 season. The youngest of the Grays when he debuted on May 1, Dalrymple went 1-for-4 against Cincinnati Reds hurler Will White.13 He put together a 15-game hitting streak to start the year, and by the end of June was hitting .381, second-highest in the league.14 Dalrymple’s outfield play was also dynamic; he led NL outfielders in putouts (128), errors (28), and range factor-per-game (2.28).

Milwaukee finished last in the league, but Dalrymple won the batting title, hitting .356 versus .351 for Paul Hines of the Providence Grays.15 In 1969 Major League Baseball’s Special Records Committee (SBRC) determined that “performances in all tie games of five or more innings shall be included in the official averages,” a practice not followed before 1885.16 That decision boosted Hines’ 1878 batting average to .358 but dropped Dalrymple’s to .354, giving Hines the title retroactively (and taking it from Dal posthumously).17

Before Dalrymple had even finished his debut season, he set a new course for the next one. Days before the Grays last game, he signed a contract to play for the Chicago White Stockings in 1879 at an annual salary reported to be $1,400.18

Dalrymple’s acquisition was part of a massive overhaul of a team that finished a disappointing .500 the year before. Only two ballplayers from Chicago’s 1878 season opener were in their 1879 Opening Day lineup: Cap Anson, in his first year as a playing manager/captain, and pitcher Terry Larkin. To help fans distinguish all the new faces, Chicago management had each player start the season wearing color-coordinated caps, belts, neckties and stocking stripes, with a unique color for each player.19 Dal’s assigned color was white.

Playing left field and batting at the top of the order, Dalrymple collected 21 hits in his first 12 games, but tapered off to hit .291 for the season, with 25 doubles, which tied for second in the NL. On defense, he struggled, making 40 errors, not only leading the league again, but setting a new NL record for outfielders. “Dalrymple is a splendid judge of a ball,” snarked the Chicago Telegraph. “That is he can take one in a store and tell whether it is well made or not. But when he is out in the field, and one is batted toward him, he is never dead sure whether it is going to drop ten rods in front or fly forty feet behind him.”20 This proved to be an eerie foreshadowing of a fateful play seven years hence.

Though Dalrymple’s defense was often atrocious, Spalding’s Base Ball Guide and Official League Book for 1880 considered his batting style “the embodiment of the faculty of free hitting.”21 “His quick eye,” the Guide added “enables him then to bring his bat with a rapid sweep up or down to the line of the ball, and, as he strikes with great force, the ball if hit fairly will go hard and far.”

Bolstered by the addition of pitcher Fred Goldsmith, two-way player Larry Corcoran, and a young Mike Kelly, the 1880 White Stockings cruised to the NL pennant. In left field for every one of those games was Dalrymple, who hit .330, with a team-high 12 triples. He topped the NL in at-bats (382), runs (91), hits (126), and total bases (175). In June and July, Dalrymple compiled a career-high 17-game hitting streak that coincided with a league-record 20-game winning streak by Chicago.22 He committed 11 fewer errors than he had the year before, and on August 31, showed his ability to not just prevent baserunners, but eliminate them, as he gunned down two at the plate in a 2-1 Chicago victory.23

A half-century later, Dalrymple recounted an epic sleight-of-hand he claimed to have pulled off late in the 1880 season during a game in Chicago against Buffalo. As he recalled, with two out, the bases loaded, and Chicago leading in the ninth, “a smoky haze had settled over the field.” Buffalo batter Ezra Sutton stepped to the plate and hit a “furious wallop” in Dalrymple’s direction.24 Dalrymple leapt as if to make a catch, and at the same time pulled “an extra ball” from his shirt, which he said he kept there in case of “emergency.” The umpire, seeing the Chicago left fielder land with a ball firmly in his grasp, called the batter out.

Though Dalrymple’s tale was more fable than fact,25 he did push the competitive envelope in other ways. He admitted to carrying a small penknife to loosen the seams on darkened used balls to force umpires to replace them with easy-to-see new ones. As former White Stocking ace Clark Griffith said about Dalrymple in 1911, “He could pull off a lot of stuff for an outfielder and get away with it in a fashion that would cause a riot nowadays.”26

In 1881 the White Stockings took over first place in late May and never let go, winning back-to-back pennants. Called the hardest hitter in the country by journalist Opie Caylor, Dalrymple hit .323 over 82 games.27 On July 2 he hit his first major league home run, off Troy’s Tim Keefe.28 Exactly one month later he became the first major leaguer considered to have been intentionally walked with the bases loaded. Trailing 5-0 in the eighth inning, Buffalo rookie hurler Jack Lynch elected to force in a run by walking Dalrymple, preferring to take his chances against the next batter, George Gore.29

Three weeks before the start of the 1882 season, Chicago’s popular president, William Hulbert, died. Without Hulbert’s steadying influence to help Anson get the most out of the team,30 Chicago stumbled out of the gate. Dalrymple’s four doubles and three triples across three mid-June games sparked Chicago to win 14 of 15, a streak that set them on a path to their third consecutive NL pennant.

On July 24 Chicago debuted new “sensible and taste-ful” short-sleeved summer uniforms, after the NL abandoned an ill-advised regulation requiring players to wear multi-colored uniforms similar to what the White Stockings tried years earlier.31 The new threads proved to be splendid batting clothes, as Chicago pasted the Cleveland Blues, 35-4, setting an NL single-game record for runs by a team that lasted 15 years.32 Dalrymple was one of five bespoke White Stockings to both collect four hits and score four times or more. For the season, he again led the league in at-bats, and he hit .295 with an excellent 130 Adjusted OPS+.

Early in the 1883 season Dalrymple was laid low for several weeks by an eye infection, which opened the door for future evangelist Billy Sunday to debut in his place.33 Following a midsummer slump,34 Dalrymple was dropped down in the batting order against lefties but responded poorly; he made 10 errors over a seven-day span. His offensive numbers finished in line with past seasons, but Chicago failed to win a fourth-straight pennant. Dalrymple did enjoy one extraordinary day at the plate on July 3, when he and Anson each doubled four times in a 31-7 demolition of Buffalo.35 Matched dozens of times since, no major leaguer has ever hit more doubles in one game.36

A number of the 121 doubles Dalrymple hit between 1879 and 1883 were ground-rule doubles knocked over the short porch in right field at Chicago’s Lake Front Park, located no more than 230 feet from home plate.37 For the 1884 season, White Stockings management reclassified those hits as home runs, a change that produced immediate and historic results.

In the first inning of Chicago’s May 29 home opener, Dalrymple hit the very first home run over Lake Front’s right field fence.38 When the opposing Detroit Wolverines came to bat, their leadoff batter George Wood did the same. The next day Dalrymple again homered to right. On August 14, he hit a pair of three-run homers at Lake Front off Buffalo’s Billy Serad, which gave him 16 on the season, surpassing Harry Stovey’s previous major league single-season high of 14, set the year before.39

Dalrymple hit 22 home runs in 1884, 18 of them at home, but teammates Ned Williamson and Fred Pfeffer hit more. Despite hitting a record-setting 142 home runs, and posting a league-high .281 batting average, Chicago finished a distant fifth to the Providence Grays. Thanks to the NL’s first season with over 100 scheduled games, Dalrymple set a new league record with 521 at-bats. He also recorded personal highs in runs scored (111) and RBIs (69).40

The White Stockings abandoned their lakeside bandbox in 1885 for West Side Park, a new ballpark on the city’s west side. Dalrymple gave up his life as a bachelor to wed Miss Minerva S. Green two days before Opening Day, then celebrated by hitting six home runs during Chicago’s five-week season-opening homestand. He only hit five more throughout the season, but 11 proved enough for the NL home run crown. Chicago hit fewer than half the number of homers they hit the year before, but held off the New York Giants in the closest pennant race in the NL’s then 10-year history. It was Dalrymple who just about sunk the Giants pennant hopes with a two-run double in the ninth inning of a White Stockings win over New York on October 1 that clinched a tie by putting Chicago five games ahead of the Gothamites with five left to play.41 The Boston Globe declared that, “Gore, Dalrymple and Kelley [sic], the mastodonic outfield of the Chicagos, have outbatted, outfielded and outrun any outfield in America this season.”42

Dalrymple proved unable to carry his late season heroics into Chicago’s “world’s series” with the American Association champion St. Louis Browns.43 He hit .269 (7-for-26) with a home run, and his Series OPS of .783 matched his regular season OPS of .782, but his shaky defense opened the door in Game Three to a five-run first inning for St. Louis. He also committed two of Chicago’s 17 errors in a sloppy Game Seven loss.44 The 1885 Series ended in a controversial draw.

After an off-season spent tending cattle on his Nebraska ranch, Dalrymple, only 28 but already graying at the temples, found himself platooned with 23-year-old right-handed hitting Jimmy Ryan. Unable to keep his batting average above .250, Dalrymple’s playing time continued to be cut by Anson who sat him out all but one game between August 23 and September 23.45 A habit Dalrymple had developed of swinging at the first pitch he saw each game didn’t help, as opposing pitchers caught on to his odd superstition, which was aimed at preventing hitless games.46 Back in the lineup for the last two weeks of the 1886 season, Dalrymple’s batting average ended up a mediocre .233, as Chicago edged out Detroit for its fifth pennant in seven years.

As was true for much of the regular season, Dalrymple had little impact in the first five games of the 1886 World Series, a rematch between Chicago and the Browns. Down three-games-to-two in the best-of-seven series, Chicago was leading Game Six in St. Louis by a score of 3-1 as the Browns came to bat in the eighth. With two out and two runners on, Dalrymple misjudged a fly ball hit toward him by Arlie Latham, breaking in when he should have stayed put.47 The ball landed behind him, allowing both baserunners to score. In the top of the ninth, with the score tied, the go-ahead run on third and two out, Dalrymple fanned on three Bob Caruthers offerings thrown out of the strike zone. A tenth-inning wild pitch by Chicago’s John Clarkson allowed the Browns’ Curt Welch to score the Series-clinching run on a play immortalized as the “$15,000 slide.”

The Denver News later quoted an un-named teammate saying “Dal’s mind was on that $525 [each winning player’s expected share] and not on the game,” and charged Dalrymple with misjudging Latham’s fly “in a style that would have disgraced an amateur.”48 Dal swore he couldn’t see the low line drive against the dark grandstand.49 Anson and Kelly reportedly accused Dalrymple of having “revenged himself” over getting benched for Ryan.50 The Sporting News concluded their Series wrap-up with the observation that “every one of the Chicagoans blamed Dalrymple for the defeat they suffered that day.”51 Decades before the term was commonly used, Dalrymple had become the very first World Series goat.52

By Thanksgiving, Spalding sold Dalrymple’s contract to the Pittsburgh Alleghenies, an American Association team that had just transferred to the NL. Spalding claimed he was reluctant to lose Dalrymple, but Dal had requested his release, feeling “a change would be beneficial.”53 Anson wasn’t sorry to see him go, an opinion made evident years later when he called Dalrymple “an ordinary fielder” whose “poor fielding cost us several games that in my estimation we should have won.”54 Sporting Life reported Dalrymple was let go due to worsening eyesight, a problem he’d long suffered with.55

Diminished or not, Pittsburgh manager Horace Phillips saw Dalrymple as an accomplished hitter who could help support the dream-team rotation that he’d pulled together: Pud Galvin, Jim McCormick, and “Cannonball” Ed Morris, who collectively won 101 games the year before. “Glad to get away from Anson’s tyrannical power,” Dalrymple terrorized him with a first-inning leadoff triple on Opening Day that sparked the Alleghenies to a home victory over the defending NL champions.56 The Chicago Tribune sarcastically referenced the negative impact on the club from jettisoning its entire 1886 outfield (Gore and Kelly had also been sold in the off-season). “If any Chicago Base Ball Club managers have any photographs or well-executed engravings of the checks received from the purchasers of Gore, Kelly, and Dalrymple, they can now go and look at them and derive some consolation therefrom in this trying hour.”57 When Dalrymple first came to bat during Pittsburgh’s first series in Chicago, he was greeted with rounds of applause and given a silver-mounted rosewood bat by “old friends and admirers.”58

Dalrymple’s season went downhill from there. Hitting .195 in mid-June, he was benched on and off for the next six weeks. But when the team’s best hitter, third baseman Alex McKinnon, lay dying from typhoid, president William Nimick named Dalrymple team captain.59 He guided Pittsburgh to its first .500 month of the year in August, but couldn’t prevent a sixth-place finish. A short-lived NL rule that counted walks as hits helped Dalrymple hit an even .300, but after MLB’s SBRC retroactively backed out walks in 1969, his adjusted average was a career-low .212.

In the waning days of the 1887 season Dalrymple haunted his former team one last time, hitting a pair of solo home runs off John Clarkson in Chicago on September 28. The first one tied the game in the eighth and the second one ended it in the tenth.60 Dalrymple’s heroics must not have alienated his former teammates. After the season he spent ten weeks barnstorming with them in cities from St. Louis to San Francisco.61

The 1888 pre-season was an uncomfortable one for Dalrymple. In line to replace Phillips as manager, Dalrymple instead lost his position as captain. His rancorous relationship with Phillips, whom he banished to the grandstand for in-game interference the year before, may have been why.62 After “old man Dalrymple” wrenched an ankle the week before Opening Day, he healed in the company of a new temporary roommate and old friend, Billy Sunday, recently acquired by the Alleghenies.63

Typical of Dalrymple’s 1888 misfortunes, a drive he hit over the center field fence during a June game in Indianapolis struck a telegraph wire and bounced back on the field, limiting him to a double.64 In August Dalrymple missed two weeks to injury after running into a fence in Washington, D.C.65 Denied the chance to play regularly after he returned, Dalrymple requested and received his release.66 He finished the season at .220 with, for the first time, a negative WAR.

Early in Dalrymple’s professional career, he’d spent several off-seasons working railroad jobs, including brakeman for the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad company.67 When Pittsburgh released him, Dalrymple went back to the rails, as a gateman on the Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad.

Not ready to ride the iron horse full-time, Dalrymple signed on with the Western Association Denver Grizzlies for the 1889 season. He played left field and filled in at third base “like a war horse” for manager Dave Rowe, spending over 40 games there.68 He also secured a victory in the first of the only two games he ever pitched as a professional (both in relief).69 Dalrymple hit for the cycle in his second game as a Grizzly and again on June 27, the latter giving him home runs in five-straight games.70 For the year Dalrymple hit .331, with 72 extra-base hits in 523 at-bats, and stole 54 bases, including six in one game.71

Back with Denver in 1890, Dalrymple hit the first home run in the Grizzlies’ new Broadway Athletic Field ballpark on April 18, but by the end of the month he was released.72 The Denver News claimed Dalrymple asked to be cut free to escape creditors.73 He’d opened a cigar store in town and took on debt to stock and outfit it, but proved unable to sell enough stogies.

Dalrymple caught on immediately with the Milwaukee Brewers of the Western Association and was warmly welcomed by the city where his professional career began. As he came to bat in his first home game, he was presented with a silver-headed cane by “friends of ’78,” then later received a gold watch.74 “Once more a colt,” Dalrymple stole 79 bases and hit .328 for third-place Milwaukee.75

Rechristened the Creams, Milwaukee started the 1891 season slowly, going 8-11. Dalrymple broke up a no-hitter in the ninth inning against Omaha in one of those losses.76 After he lined out three doubles in a 12-0 whitewashing of Lincoln, the Daily Nebraska State Journal joked that Dalrymple “hasn’t forgotten to use the stick even if he did play one-old-cat with Israel Putnam, Lord Cornwallis and a few others of revolutionary fame.”77 Milwaukee got hot soon after and surged to the top of the Association standings. “Often mak[ing] sick the hearts of prize pitchers,” Dalrymple led the Association in hitting in late July.78 A few weeks later, Milwaukee moved up to the major-league American Association, taking over the franchise formerly held by Cincinnati’s Kelly’s Killers, a team whose manager and namesake was King Kelly.

Dalrymple went 4-for-4 for the once-again Brewers in his second game back in the majors, and in Milwaukee’s home debut, scored five runs in a 30-3 lambasting of the Washington Statesmen.79 Two days later, on September 12, Dalrymple hit for the cycle. After tripling in a run in the opening frame, Dalrymple “illustrated to the excited multitude the law of excentric [sic] projection” by hitting a ball well over the right field fence.80 The Washington Post reported the ball went through a window of a nearby house.81 The cycle was the first of Dalrymple’s major league career; the home run his last.

Dalrymple’s final game was also memorable for what happened afterwards. Looking to boost their finances, the Brewers and Columbus Solons had agreed to move their season-ending two-game series to Minneapolis. Milwaukee won the series opener on October 2 with Dalrymple going 0-for-4. After the game, a local deputy sheriff seized the gate receipts ($120) to satisfy a judgment against Dalrymple for an unpaid debt of $98.82 Despite carrying his highest major league batting average in ten years (.311), Dalrymple did not play the next game. In the coming months, Dalrymple would stray even further from the “quiet and proper in decorum” image he’d developed.83

Rumored to be missing in November, Dalrymple turned up weeks later in Tacoma, Washington, playing house with a Milwaukee “woman of questionable reputation.”84 Undeterred, Mrs. Dalrymple traveled to Tacoma and persuaded Abner to return home with her.

Over the next four years Dalrymple bounced around the minor leagues. Favorably impressed with the Evergreen State from his scandalous time there, he signed on with the Spokane Bunchgrassers of the Class-B Pacific Northwest League for the 1892 baseball season. With his watchful wife in the stands for every game, Dalrymple hit an even .300 playing all three outfield positions, and occasionally first base, for manager Ollie Beard.85 Dalrymple left at the end of July, dismissed for “indifferent work and cranky actions in the field” according to the local papers. Dal insisted his contract had ended, coinciding with the end of a leave-of-absence from his job with the Northern Pacific Railroad.86

Dalrymple followed Beard to Macon, Georgia, and the Class-B Southern Association in June 1893, where he played in 30 games before returning to his railroad job. The following May he played in one game for Minneapolis of the Western League, then signed on with Indianapolis of the same league. Chosen to be team captain by manager Bill Sharsig, “Uncle Abner,” as one local newspaper called him, stayed on for the whole season, hitting .355 for the Hoosiers.87

Dalrymple reunited with Beard again in 1895, back in the Southern Association. Playing for Evansville at age 37, “Grandpa Abner” did well against hurlers from both ends of the record-book.88 In an April exhibition against the NL Cleveland Spiders, he reached base twice against Cy Young, the winningest pitcher in major league history,89 and on June 4 he hit a game-winning homer off Crazy Schmit, who owns the second-lowest winning percentage of any major-league pitcher with at least 40 decisions (.163).90 For the year, Dalrymple hit .292 over 49 games with 12 stolen bases.91

Done playing professionally, Dalrymple joined various “farmer boys” teams over the next decade, first in Morris, Minnesota, where he and his wife lived, then in Crookston, Moorhead, and Fargo.92 He last played competitively in 1907 with a semipro team in East Grand Forks, Minnesota.

As baseball transitioned from career to hobby for Dalrymple, he worked as a brakeman on upper Midwest routes for the Northern Pacific, later rising to the level of conductor. He retired in 1928, with 36 years of service, at the age of 71.93

Several years before his retirement as a railroader, Dalrymple’s wife died. He remarried in 1926, to Margaret Alderson Glasgow, a widowed former “school-day sweetheart” from Warren.94

On January 25, 1939, Dalrymple died at his home in Warren after a brief illness.95 Recalling his brief stint among NL home run leaders, the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph called Dalrymple “the Babe Ruth of his era.”96 A more apt epitaph might be the lyrical description of Dal that Clark Griffith once offered: “A smooth old soul.”97

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

The author compiled game logs for Dalrymple’s professional career from game summaries and box scores published in newspapers which regularly covered the teams on which he played, primarily the Freeport (Illinois) Journal, Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, Chicago Inter Ocean, Detroit Free Press, St. Paul Globe, Minneapolis Tribune, Omaha World Herald, Spokane Review, Macon Telegraph, Indianapolis Journal, Evansville Journal, Sporting Life, and New York Clipper. He also obtained pertinent material from Bill McMahon’s SABR biography of Al Spalding. In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted FamilySearch.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, Stathead.com, Baseball-Almanac.com, and Statscrew.com.

Notes

1 “’Booze’ and Base-Ball,” Chicago Tribune, September 23, 1887: 3.

2 “Diamond Field Gossip,” New York Clipper, April 6, 1895: 73.

3 “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 17, 1884: 8.

4 “Drift of the Diamond,” Pittsburgh Press, April 3, 1900: 5.

5 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (Free Press: New York, 2001), 713. James compared ballplayers across all major league eras, ranking Dalrymple 93rd all-time. Nineteenth-century left fielders that James rated ahead of Dalrymple (defined by the author as those with a majority of their plate appearances before 1901), were, in order, Ed Delahanty, Jesse Burkett, Joe Kelley, Jim O’Rourke, Harry Stovey, Tip O’Neill, Charley Jones, Kip Selbach, and Elmer E. Smith.

6 Orin Crooker, “When Billy Sunday Hit the Trail,” Nashville Baptist and Reflector, April 13, 1916: 10.

7 Hy Turkin and S.C. Thompson, The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1951), 72; “Illinois Deaths and Stillbirths, 1916-1947”; “Ab Dalrymple, ‘Babe Ruth’ of the ‘70s, Dies,” Freeport (Illinois) Journal-Standard, January 26, 1939: 1. The Freeport Journal also listed September 19 as Dalrymple’s date of birth in an extensive article they published more than a decade before his death in which he shared details of his baseball career. “Al (sic) Dalrymple, ‘Babe Ruth’ of ‘70s, Retires from Railroad Work,” Freeport Journal-Standard, September 22, 1928: 4. The author was unable to uncover any contemporary record of Dalrymple’s birth in records available online from Lafayette County, Wisconsin, where Gratiot is located. The headstone at Dalrymple’s gravesite does not help eliminate this uncertainty as it lists only his year of birth.

8 “Abner Dalrymple, Champ Batter in 1878, Will Retire,” Billings (Montana) Gazette, September 23, 1928: 8.

9 “Base Ball,” Freeport Journal, July 19, 1876: 8; Chicago Tribune, July 22, 1876: 5.

10 “Good Enough,” Milwaukee News, May 19, 1877: 4; “The Milwaukee Club,” Chicago Tribune, November 11, 1877: 8. A fanciful retelling of Dalrymple’s first days with Milwaukee a decade later described him as sporting large, sunburned hands, long hair, and “the most ungainly [gait] imaginable.” The account erroneously claimed that Dalrymple homered in his first at-bat against a “League” pitcher and added three more hits before the game ended. “Liners,” Detroit Free Press, May 9, 1887: 5.

11 “That Game,” Milwaukee News, June 21, 1877: 4; “Champions,” Milwaukee News, September 7, 1877: 4.

12 “Base Ball,” Milwaukee News, July 13, 1877: 4.

13 “Base-Ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 2, 1878: 8.

14 “Personals,” Memphis Appeal, June 26, 1878: 5. Batting streak information based on game logs compiled by the author. Dalrymple’s career-opening streak may have been an NL record. Between 1901 and 2023, the longest hitting streak at the start of an NL career is 17. “Jordan Walker’s landmark debut hit streak of 12 games ends vs. Pirates,” ESPN website, April 14, 2023, https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/36183943/jordan-walker-landmark-debut-hit-streak-12-games-ends-vs-pirates

15 “The ‘Guide’ for 1879,” Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1879: 12. The league’s official statistics were released in A.G. Spalding’s Base Ball Guide for 1879. That publication included a full page “portrait of young Dalrymple, the leading batsman of 1878.” See also, “Base Ball,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 9, 1879: 3.

16 John Thorn, “Why Is the National Association Not a Major League … and Other Records Issues,” Our Game website, May 4, 2015, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/why-is-the-national-association-not-a-major-league-and-other-records-issues-7507e1683b66.

17 At the time that Dalrymple lost his crown, he was the third youngest, behind Ty Cobb and Al Kaline, to have won a major league batting title, and one of only four rookies to have done it. Ross Barnes of the 1876 White Stockings, Pete Browning of the 1882 American Association Louisville Eclipse, and Tony Oliva of the 1964 American League Minnesota Twins were the other rookies to lead their respective leagues in hitting. Since Dalrymple was originally recognized as the 1878 batting champion, Baseball-Reference.com lists both Hines’ and Dalrymple’s 1878 batting averages in bold font, which represents league leadership.

18 “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 11, 1878: 5; “General Notes,” Cleveland Leader, September 20, 1878: 8. In later years, Dalrymple claimed that his salary was the highest of any Chicago ballplayer in 1879. That claim morphed upon his death into an assertion that he was “the highest paid ball player of his day.” “Former Star of Diamond Relates Past Experiences,” Des Moines Register, October 14, 1928: 24; “Abner Dalrymple Dies in West,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, January 27, 1939: 26.

19 “Notes of the Game,” Chicago Tribune, March 16, 1879: 12. The use of differing-colored uniforms was a practice that Chicago had first adopted several years earlier but abandoned.

20 “Base Ball,” Chicago Telegraph, August 1, 1879: 1.

21 Spalding’s Base Ball Guide and Official League Book for 1880 (Chicago: A.G. Spalding & Bros., 1880), 20.

22 “Baseball Notes,” New York Clipper, July 10, 1880: 122. Abner’s streak ended during the same game in which the team’s winning streak ended, an extra inning shutout loss on July 10 to Cleveland’s Jim McCormick. In one game of Dalrymple’s streak, he and two other normally left-handed-hitting teammates, Gore and Corcoran, elected to bat right-handed against Lee Richmond, at that time arguably the nastiest left-hander in the league. “Chicago vs. Worcester,” Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1880: 13.

23 “Chicago vs. Troy,” Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1880: 3. Dalrymple was the offensive star of the game as well, doubling twice and scoring Chicago’s only two runs in their triumph over the Troy Trojans.

24 “Former Star of Diamond Relates Past Experiences,” Des Moines Register, October 14, 1928: 24.

25 Various details of Dalrymple’s story don’t match contemporary records. Chicago did win two relatively close games over Buffalo at the close of the 1880 season, and won two more post-season exhibition games directly after the season ended, but game summaries in Chicago and Buffalo newspapers made no mention of a Buffalo rally in the ninth, nor of Dalrymple making a game-ending or otherwise extraordinary catch. In addition, Sutton never wore a Buffalo jersey; he played for the Boston Red Stockings in 1880. Chicago also won a thriller over Buffalo to end the 1882 season, but again there was no report of a great ninth-inning play by Dalrymple. “Chicago 6, Buffalo 5,” Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1882: 9.

26 W.A. Phelon, “One on Ab Dalrymple,” Pittsburg Headlight, August 1, 1911: 8.

27 “So Glad!” Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1881: 10. Anson won the batting crown, hitting .399.

28 “Chicago-Troy,” Chicago Inter Ocean, July 4, 1881: 3.

29 “Chicago vs. Buffalo,” Chicago Tribune, August 3, 1881: 4. Lynch’s decision appears to have been based on events of that game and not prior performance. Dalrymple had singled off Lynch earlier in the game but had been a modest 6-for-23 (.261) over the previous two weeks. In two earlier games against Buffalo, he’d gone 3-for-10, with no extra base hits, and was a modest 1-for-5 against Lynch. Gore was 3-for-10 batting against Lynch coming into the game but had been held hitless before the eighth inning.

30 “Gossip of the Game,” Chicago Tribune, May 28, 1882: 16.

31 “1882 Chicago,” Threads of Our Game website, https://www.threadsofourgame.com/1882-chicago/, accessed November 20, 2023.

32 “Chicago 35, Cleveland 4,” Chicago Tribune, July 25, 1882: 7. That record stood until June 29, 1897, when the Chicago Colts, as they were then known, scored 36 against the Louisville Colonels. Justin Sweetwood, “The Highest-Scoring Games in MLB History, The Analyst.com website, July 19, 2023, https://theanalyst.com/na/2023/07/highest-scoring-games-in-mlb-history/

33 “Fly Tips,” Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1883: 8; “Chicago vs. Boston,” New York Clipper, June 2, 1883: 172. Roughly a century before the term first entered baseball vernacular, Sunday took a “golden sombrero” in his debut, fanning four times.

34 See e.g., “Notes,” Buffalo Commercial, August 15, 1883: 3. Though Chicago faced southpaws infrequently during the 1883 season, dropping Dalrymple in the batting order seemed warranted. He hit only .214 against the few southpaws he faced that season (6-for-28), versus over .300 against right-handers.

35 “Chicago, 31; Buffalo, 7,” Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1883: 7.

36 From 1901 through the 2023, 50 major leaguers have hit four doubles in one game, most recently Jarren Duran of the Boston Red Sox on July 2, 2023. As Negro League game statistics are incorporated into official major league databases, that number will likely grow, or the record might even be eclipsed.

37 John C. Tattersall, “Clarifying an Early Home Run Record, Baseball Research Journal, January 1972, https://sabr.org/journal/article/clarifying-an-early-home-run-record/.

38 “Chicago-Detroit,” Chicago Inter Ocean, May 30, 1884: 3.

39 “Chicago, 17; Buffalo, 10,” Chicago Tribune, August 15, 1884: 2.

40 Though not an official NL statistic until 1920, the Chicago Tribune first published “runs batted home” by Chicago ballplayers in 1880. “Team Record,” Chicago Tribune, July 11, 1880: 6.

41 “Beaten a Third Time,” Philadelphia Times, October 2, 1885: 4. “When Dalrymple made his great drive,” described the Philadelphia Times, “the crowd broke into a thunderous cheering, the contagion apparently reaching to everyone present save the immediate supporters of the New York nine, and even some of these appeared to catch the infection.”

42 “Total Bases,” Boston Globe, July 8, 1885: 5.

43 “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, October 20, 1885: 3.

44 “St. Louis Beats Chicago,” Boston Globe, October 17, 1885: 2; “No Longer Champion,” Chicago Tribune, October 25, 1885: 11.

45 While cooling his heels, Dalrymple attended the inaugural meeting of the Base Ball Players’ Brotherhood, organized by the Giants’ John Montgomery Ward. Foreshadowing changes yet to come, Dalrymple was mistakenly identified as a representative not from Chicago, but rather Pittsburgh, then still a member of the American Association. “Base Ball Brotherhood,” Semi-Weekly Age (Coshocton, Ohio), August 30, 1886: 2.

46 “Chicago Wild with Joy,” Philadelphia Times, July 18, 1886: 11.

47 “A Chicago Account of Chicago’s Defeat,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 26, 1886: 5.

48 “The National Game,” Denver News, November 2, 1886: 7.

49 “Base-Ball,” Chicago Tribune, November 27, 1886: 2.

50 “Sporting Events,” Oshkosh (Wisconsin) Northwestern, October 30, 1886: 1.

51 “At the Lindell” The Sporting News, October 30, 1886: 3.

52 For a detailed analysis of whether Dalrymple’s goat label was warranted, see Dennis Pajot, “Baseball’s First World Series Goat: Abner Dalrymple and Game Six of the 1886 World Series,” Seamheads website, April 6, 2009, https://seamheads.com/blog/2009/04/06/baseballs-first-world-series-goat-abner-dalrymple-and-game-six-of-the-1886-world-series/

53 “Base Ball,” Boston Herald, November 27, 1886: 5. Sporting Life reported that Dalrymple’s heart was broken when he lost playing time to Jimmy Ryan, and that “he made no secret of his desire to leave Chicago.” His resolve to leave was hardened after his teammates blamed the team’s World Series loss on him. Dalrymple going to the Alleghenies was also rumored to have been part of the deal that Spalding helped broker to get Pittsburgh to move to the NL. “Dalrymple for Pittsburg,” Sporting Life, December 1, 1886: 1.

54 Adrian Anson, A Ball Player’s Career (Chicago: Era Publishing, 1900), 114.

55 “Not Much,” Sporting Life, December 15, 1886: 2. Dalrymple’s eyesight was first rumored to have been failing shortly before the Series. Immediately after, The Sporting News shared with its readers that “Dalrymple is troubled with an affection of the eyes and cannot see as well as of old.” The problem was so severe that sometime during the season he traveled to Philadelphia for eye surgery. Whatever the issue was, it didn’t seem to worsen. Dalrymple continued to play for many years after the 1886 World Series with scant mention of it in the press. “Baseball Gossip,” Streator (Illinois) Free Press, October 22, 1886: 1; The Sporting News, October 30, 1886: 4; “Fly Tips,” Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1883: 8; “Base-Ball,” Burr Oak (Kansas) Reveille, August 9, 1883: 2; “Sport-Pastime Drift,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 5, 1886: 10.

56 “Diamond Points,” Boston Globe, April 19, 1887: 3; “A Brilliant Victory,” Pittsburg Post, May 2, 1887: 6.

57 Untitled, Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1887: 4.

58 “The Battery Beat ‘Em,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1887: 6.

59 “First Baseman M’Kinnon Dead,” Pittsburg Post, July 25, 1887: 6; “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, July 25, 1887: 3.

60 “Dalrymple’s Home Runs,” Pittsburg Post, September 29, 1887: 6.

61 “White and Brown,” Sporting Life, November 9, 1887: 3. In addition to Dalrymple, Chicago’s barnstorming team included several other ballplayers they picked up from other teams, like American Association standouts Bid McPhee and Tony Mullane. Chris Bouton, “When Baseball Was King,” Hardball Times website, November 26, 2019, https://tht.fangraphs.com/when-baseball-was-king/; “The Chicagos Beaten,” San Francisco Examiner, December 25, 1887: 6; “At Central Park,” San Francisco Examiner, January 9, 1888: 8.

62 “Pittsburg Pencilings,” Sporting Life, October 5, 1887: 1; “Sporting News and Notes,” Milwaukee Journal, March 23, 1888: 1. Clearly aware of friction between Dalrymple and Phillips, when Nimick appointed infielder Fred Dunlap captain he made clear that Phillips was to stay out of the new captain’s hair during games.

63 “Earned and Stolen Bases,” Lynn (Massachusetts) Item, April 12, 1888: 4; “Sporting,” Pittsburg Press, April 19, 1888: 5. About the pair, the Pittsburg Press said, “two quieter or more gentlemanly men in any line of business it would be hard to find.”

64 “Base Ball Matters,” Chicago Tribune, June 28, 1888: 6.

65 “Kuehne’s Big Hit,” Pittsburgh Post, August 14, 1888: 6; “Diamond Dust,” Chicago Inter Ocean, September 2, 1888: 12. While he was recuperating, Dalrymple took a turn as a ballpark gatekeeper. “Earned and Stolen Bases,” Lynn Item, August 28, 1888: 4.

66 “Dalrymple’s Complaint,” Pittsburgh Post, September 12, 1888: 8.

67 “Diamond Dust,” Cleveland Leader, February 9, 1881: 5; “Base Ball,” Cleveland Leader, December 27, 1881: 5; “Base Ball Gossip from Chicago,” Boston Herald, April 11, 1883: 5.

68 Roxy, “Rowe’s Hard Row,” Sporting Life, July 3, 1889: 6.

69 “A Day for the Sluggers,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, May 24, 1889: 2. Dalrymple entered Denver’s May 23 contest against the Sioux City Corn Huskers in the middle of an eighth-inning rally that pulled Sioux City to within two runs. After escaping that inning, he recorded a 1-2-3 ninth. Charged with two runs according to Baseball-Reference records, it’s unclear whether Dalrymple would’ve met current criteria for earning a save.

70 “Denver 23, Des Moines 4,” Omaha Bee, April 22, 1889: 2; “Down They Go,” St. Paul Globe, June 28, 1889: 6.

71 “Denver 5, Milwaukee 2,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Herald, August 15, 1889: 5.

72 “Omaha an Easy Mark,” St. Paul Globe, April 19, 1890: 5.

73 “Dalrymple Goes to Milwaukee,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 30, 1890: 9; “Denver Catches On,” Denver News, May 4, 1890: 4.

74 “Dalrymple Presented with a Cane,” Chicago Tribune, May 15, 1890: 6; “Caught on the Fly,” Central City (Nebraska) Courier, May 29, 1890: 7.

75 “Diamond Gossip,” Omaha World-Herald, July 20, 1890: 7; “It is All Over Now,” St. Paul Globe, October 1, 1890: 5; “The Western,” Sporting Life, October 25, 1890: 8.

76 “Dad Clarke Did the Work,” Omaha Bee, April 18, 1891: 2. The pitcher that Dalrymple denied a no-hitter to was Dad Clarke of the Omaha Lambs. Omaha’s victory in that game ended a string of 17-consecutive losses to Milwaukee.

77 “Short Hits,” Daily (Lincoln) Nebraska State Journal, April 21, 1891: 2.

78 “Base Ball Notes,” Leavenworth (Kansas) Standard, July 24, 1891: 1.

79 “Louisville vs. Milwaukee,” New York Clipper, August 29, 1891: 424; “Sat Down Upon Senators,” Milwaukee Journal, September 11, 1891: 2.

80 “Took the Third Game,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 13, 1891: 7.

81 “Nearing the Tail End,” Washington Post, September 13, 1891: 3.

82 “Minneapolis Globules,” St. Paul Globe, October 4, 1891: 10. This was Dalrymple’s second run-in with the law over money that season. Passing through Chicago on his way to Milwaukee’s season opener, he was detained by a local constable over a suit claiming he’d failed to repay a $200 debt. “Dalrymple and the Constable,” Chicago Tribune, August 19, 1891: 7.

83 “A Player’s Folly,” Sporting Life, January 2, 1892: 1.

84 “The Northwest Field,” Portland Morning Oregonian, December 24, 1891: 2.

85 “Gossip of the Diamond,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 12, 1892: 3.

86 “Players Released,” Sporting Life, August 20, 1892: 1; “Notes of the Game,” Spokane Review, August 2, 1892: 8.

87 “The Ball Club at Home,” Indianapolis News, May 29, 1894: 8; “Western Work,” Sporting Life, October 27, 1894: 4.

88 “Sporting Notes,” Pittsburgh Post, March 11, 1895: 6.

89 “Held ‘Em to Four,” Evansville (Indiana) Courier, April 10, 1895: 1; “One, Two, Three,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, April 10, 1895: 5.

90 “Dal’s Lucky Hit,” Evansville Journal, June 5, 1895: 1.

91 Based on the author’s game log. Year-end averages published by the New York Clipper show Dalrymple hit .314. “Official Averages,” New York Clipper, December 21, 1895: 667. Dalrymple’s final professional season included maybe the most bizarre play of his career. Down three runs in the ninth inning of a game in New Orleans, Dalrymple hit an apparent leadoff home run into the grandstand. During his home run trot, he was told by Beard to stop at third; “in order to worry the pitcher.” Looking to outwit Beard, Pelican manager Abner Powell had his catcher position himself at the backstop fence and urged the pitcher to ignore Dalrymple (i.e. allow him to steal home). Beard’s ploy “worked” as Evansville scored three times to win the game. “Evansville 6, New Orleans 5,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 13, 1895: 8.

92 “Dalrymple Is a Conductor,” Buffalo Enquirer, April 17, 1902: 4; “Shortstops,” Morris (Minnesota) Tribune, May 27, 1896: 5; “Morris vs Turners,” Morris Tribune, July 6, 1898: 1; “Abner Dalrymple, Champ Batter in 1878, Will Retire,” above.

93 “Abner Dalrymple, Champ Batter in 1878, Will Retire.” Dalrymple, injured in at least one train accident, was involved in several others that resulted in fatalities, including one outside of Minneapolis in 1902 that he was initially blamed for. “Seven Injured in N.P Train Wreck,” Morris Tribune, March 23, 1917: 1. “Verdict of Accidental Death,” Little Falls (Minnesota) Transcript, February 16, 1900: 4; “Two Killed in Collision of Freight Trains in West,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, December 13, 1902: 2.

94 “Abner Dalrymple, ‘Babe Ruth’ of ’76, Marries Widow,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, September 22, 1926: 1; “Babe Ruth of 80’s, Retired Rail Man, Visits Here with Bride,” Minneapolis Star, June 25, 1929: 3.

95 That same day, the first members of the fourth class to enter the Baseball Hall of Fame were announced, less than six months ahead of the Hall’s opening. The inductees revealed by the Baseball Writers Association that day were George Sisler, Eddie Collins, and Willie Keeler. Whitney Martin, “Sisler, Collins, Keeler Voted to Hall,” (Phoenix) Arizona Republic, January 25, 1939: 9.

96 “Abner Dalrymple Dies in West,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, January 27, 1939: 26. In first reporting Dalrymple’s death, Sun-Telegraph columnist Harry Keck mistakenly referred to Dalrymple as Abner Doubleday, another Abner of early baseball fame. With centennial celebrations then underway to commemorate Doubleday’s supposed invention of baseball in 1839 (a fiction long since debunked), the mistake was understandable. Harry Keck, “Vignettes of Sport,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, January 28, 1939: 12.

97 W.A. Phelon, “One on Ab Dalrymple,” Pittsburg Headlight, August 1, 1911: 8.

Full Name

Abner Frank Dalrymple

Born

September 9, 1857 at Gratiot, WI (USA)

Died

January 25, 1939 at Warren, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.