Dennis Eckersley: The Last Thousand-Hundred Man

This article was written by Douglas Jordan

This article was published in Spring 2020 Baseball Research Journal

If you pick the baseball milestone carefully enough, you can always reduce the number of players that qualify to one. For example, the only player to hit more than 72 home runs in a season is Barry Bonds. He hit 73 dingers in 2001. Second on the list is Mark McGwire with 70 in 1998. The selection of 72 as a specific cutoff leaves Bonds as the only qualifier. But choosing a cutoff this way is suspect because it’s arbitrary. Sufficiently large round numbers may seem just as arbitrary as qualifying values, but getting 3,000 hits means a batter has had a great career. Three hundred wins is a great career for a pitcher.

It’s not unusual to combine round numbers as qualifying criteria. The question that sparked the idea for this paper is this: how many players have appeared in 1,000 games and have thrown 100 complete games? Individually, neither of these milestones is unique. About 1,600 position players have played in at least 1,000 games and almost 400 pitchers have thrown at least 100 complete games. But to get to 1,000 appearances as a pitcher is much more difficult. Cy Young pitched for 22 years and appeared in only (!) 906 games as a pitcher. That’s why almost all of the 16 pitchers who have appeared in more than 1000 games are modern relief pitchers. Jesse Orosco heads the list with 1,252 games played. But relief pitchers, by definition, don’t throw complete games. So in order to appear in 1,000 games, and throw 100 complete games, a pitcher had to have a successful (and lengthy) career as both a starting pitcher and a relief pitcher. Give some thought to whom you think might qualify in both categories.

There are actually a number of players who meet these criteria, but most of them had a career path that began as a pitcher and later transitioned to position player rather than starter turned reliever. The most famous of the group is Babe Ruth. Ruth appeared in 2,503 games in his career, mostly as an outfielder. But he came up as a pitcher and threw in 163 games. He went 94–46 and had a career ERA of 2.28 with 107 complete games. There are five nineteenth century players who followed a similar pattern of starting as a pitcher and switching to a position player. These players include Kid Gleason (1,968 games, 240 complete games), John Ward (1,827 games, 245 complete games), Cy Seymour (1,529 games, 105 complete games), Elmer Smith (1,237 games, 122 complete games), and Dave Foutz (1,136 games, 202 complete games). More recently, over his 25-year career (1959–1983) Jim Kaat pitched in 898 games and completed 180 games. Kaat also appeared in 106 additional games only as a pinch hitter or pinch runner, bringing his total number of appearances up to 1,004.

But beside Kaat (who needed over 100 non-pitching appearances to get there), the only starter turned reliever to meet the 1,000 appearance and 100 complete game standard is Dennis Eckersley. The purpose of this article is to celebrate Eckersley’s accomplishments. He is almost certainly the last pitcher who will accomplish this twin feat since it is becoming increasingly uncommon for starting pitchers to complete games. All data in this article are from Baseball-Reference.com.

Other Starters Turned Reliever

Are there other pitchers who could possibly qualify? One player that immediately comes to mind when thinking of starters who later pitched as relievers is John Smoltz. Smoltz had a great 21-year career that culminated with his election to the Hall of Fame in 2015. But his time as a starting pitcher was mostly during the 1990s or later, when it became less common for starters to go nine innings. And he pitched as a reliever for only four years. Smoltz wound up with 723 appearances, 53 complete games, and 154 saves. Tom Gordon is another starter who turned into a reliever. He spent ten of his 21 years as a starter or swingman, but compiled only 18 complete games. He spent 11 years as a reliever earning 158 saves and a total of 890 appearances. Bob Stanley also pitched in both roles during his career. He wound up with 637 appearances and 21 complete games in his 13-year career. Kerry Wood finished his 14-year career with 446 appearances, 11 complete games, and 63 saves. Finally, Rick Honeycutt pitched in 797 games and compiled 47 complete games during his 21-year career. The data for these other dual-role pitchers put Eckersley’s accomplishment into perspective. It’s very difficult to pitch 100 complete games and appear in over 1,000 games.

Eckersley Career Summary

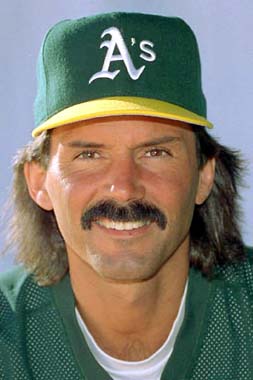

Eckersley started his major-league career with the Cleveland Indians in 1975 at 20 years of age. He was an All-Star for the Tribe in 1977 and threw a no-hitter that year1 before being traded to the Red Sox in 1978. In his debut year with Boston he went 20-8 with a 2.99 ERA. He made another All-Star appearance with the Red Sox in 1982. The Cubs were looking for pitching help in 1984, so the Red Sox traded Eckersley and Mike Brumley to Chicago in exchange for Bill Buckner. This is how Buckner got to the Red Sox before making his infamous error during the 1986 World Series. Eckersley developed some arm problems during his three-year tenure with the Cubs and was traded to the Oakland A’s before the 1987 season.

Given the arm problems that Eckersley had been having, A’s manager Tony La Russa decided to use him out of the bullpen instead of as a starter. Over the course of about two seasons, Eckersley’s role evolved to where he became one of the first relievers to be used as a one-inning closer. He thrived in the role. Eckersley won both the Cy Young award and the MVP award in 1992 when he had 51 saves and a 1.91 ERA. He pitched for Oakland for nine years earning a total of 320 saves in 525 games with a 2.74 ERA. Eckersley went to St. Louis in 1996 where he earned 66 more saves in two years before finishing his career at age 43 back in Boston in 1998. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2004. Since the end of his playing career, he has worked in broadcasting with the New England Sports Network (working Red Sox games) and TBS.

The Numbers, First Half of Career

Eckersley’s career divides neatly into two halves. He was a starting pitcher from 1975–1986 and almost exclusively a reliever from 1987–1998. This makes it natural to divide his career accomplishments into these two portions of his career. The numbers show that he was an above-average starter before transitioning to one of the best relievers of all time. Table 1 shows selected statistics from when he was a starting pitcher.

Table 1: Dennis Eckersley Selected Starting Pitcher Data and Comparisons

|

Yrs. |

W |

L |

ERA |

G |

CG |

IP |

SO |

BB |

ERA+ |

WHIP |

|

|

Dennis Eckersley |

12 |

151 |

128 |

3.67 |

376 |

100 |

2496 |

1627 |

624 |

111 |

1.212 |

|

Tommy John |

26 |

288 |

231 |

3.34 |

760 |

162 |

4710.1 |

2245 |

1259 |

111 |

1.283 |

|

Dwight Gooden |

16 |

194 |

112 |

3.51 |

430 |

68 |

2800.2 |

2293 |

954 |

111 |

1.256 |

|

Sid Fernandez |

15 |

114 |

96 |

3.36 |

307 |

25 |

1866.2 |

1743 |

715 |

111 |

1.144 |

|

Josh Beckett |

14 |

138 |

106 |

3.88 |

335 |

12 |

2051 |

1901 |

629 |

111 |

1.232 |

|

Jack McDowell |

12 |

127 |

87 |

3.85 |

277 |

62 |

1889 |

1311 |

606 |

111 |

1.302 |

ERA+ is 100*[leagueERA/ERA] adjusted to the player’s ballpark(s)

WHIP is Walks and Hits per Inning Pitched

In order to put the starting pitcher portion of his career into perspective, a group of starting pitchers was selected that had the same career ERA+ as Eckersley did during the first half of his career. The statistic ERA+ is superior to pure ERA because it accounts for both league ERA and the ballpark the player pitched in. Eckersley’s ERA+ as a starter was 111. This means that, on average over the course of his career, the league ERA was 11 percent higher than his ERA. However, it is more intuitive to think of the inverse of ERA+. The inverse of 111 multiplied by 100 is 0.901. This means that all of the pitchers in Table1 had a career ERA that was about 90 percent of the league ERA, on average. They are all better than average pitchers over the full course of their careers.

Although there are 312 pitchers who have a career ERA+ above 111, the accomplishments of the pitchers in Table 1 are still impressive. Gooden and McDowell both won a Cy Young Award. Beckett was the MVP of the 2003 World Series and the 2007 ALCS. Eckersley’s two All-Star appearances (as a starting pitcher) are in line with the others. Fernandez had two, Beckett and McDowell had three, and Gooden and John had four All-Star appearances.

From a numerical perspective, Table 1 shows that Eckersley’s WHIP is better than all but Fernandez. This is a good indication of his control. He didn’t walk too many batters. Most germane to this article is his 100 complete games. Of modern pitchers, John has 62 more complete games, but it took him 26 years (the second longest career ever for a pitcher, Nolan Ryan pitched for 27 years!) to get that many. During his first two years with Boston (1978 and 1979), Eckersley had consecutive seasons of 16 and 17 complete games. These represent 46 percent and 52 percent respectively of his starts those two seasons. In old-school style, he liked to finish what he started. To summarize, even though his career as a starting pitcher was not Hall of Fame worthy, his starting career ERA+, and these comparisons, show that he was a very good starting pitcher. Finally, it is interesting to note that Randy Johnson also finished his career with exactly 100 complete games in the 618 games he pitched in. Johnson’s career ERA+ was 135.

The Numbers, Second Half of Career

Eckersley got even better after his age 31 season in 1986. Not only did he manage to pitch for an additional 12 years as a relief pitcher, but his pitching numbers improved dramatically even though he was older. Table 2 is similar to Table 1 except that it only includes his statistics for the second half of his career as a relief pitcher. Pitchers in Table 2 after Eckersley are listed in order of career saves.

Table 2: Dennis Eckersley Selected Relief Pitcher Data and Comparisons

|

Yrs. |

W |

L |

ERA |

G |

SV |

IP |

SO |

BB |

ERA+ |

WHIP |

|

|

Dennis Eckersley |

12 |

46 |

43 |

2.96 |

695 |

387 |

789.2 |

774 |

114 |

136 |

0.999 |

|

Mariano Rivera |

19 |

82 |

60 |

2.21 |

1115 |

652* |

1283.2 |

1173 |

286 |

205* |

1.000 |

|

Trevor Hoffman |

18 |

61 |

75 |

2.87 |

1035 |

601 |

1089.1 |

1133 |

307 |

141 |

1.058 |

|

Lee Smith |

18 |

71 |

92 |

3.03 |

1022 |

478 |

1289.1 |

1251 |

486 |

132 |

1.256 |

|

Francisco Rodriguez |

16 |

52 |

53 |

2.86 |

948 |

437 |

976 |

1142 |

389 |

148 |

1.155 |

|

John Franco |

21 |

90 |

87 |

2.89 |

1119 |

424 |

1245.2 |

975 |

495 |

138 |

1.333 |

|

Billy Wagner |

16 |

47 |

40 |

2.31 |

853 |

422 |

903 |

1196 |

300 |

187 |

0.998 |

|

Jonathan Papelbon |

12 |

41 |

36 |

2.44 |

689 |

368 |

725.2 |

808 |

185 |

177 |

1.043 |

|

Eckersley (total career) |

24 |

197 |

171 |

3.50 |

1071 |

390 |

3285.2 |

2401 |

738 |

116 |

1.161 |

*All-time career record

During the second half of his career, Eckersley lowered his ERA from 3.67 to 2.96, his WHIP from 1.212 to 0.999 and improved his ERA+ from 111 to 136. The improvement in ERA+ means that on average he had an ERA about 74 percent (1/1.36) of the league ERA for those 12 years. His control improved dramatically, too. As a starter he walked a batter every 4.0 innings (2496/624) but as a reliever he walked a batter only every 6.9 innings (790/114). His strikeout to walk ratio went from 2.6 as a starter to 6.8 as a reliever. Even taking into account the different styles of pitching required to be a starter versus being a reliever, these are significant improvements as he got older.

During the second half of his career, Eckersley lowered his ERA from 3.67 to 2.96, his WHIP from 1.212 to 0.999 and improved his ERA+ from 111 to 136. The improvement in ERA+ means that on average he had an ERA about 74 percent (1/1.36) of the league ERA for those 12 years. His control improved dramatically, too. As a starter he walked a batter every 4.0 innings (2496/624) but as a reliever he walked a batter only every 6.9 innings (790/114). His strikeout to walk ratio went from 2.6 as a starter to 6.8 as a reliever. Even taking into account the different styles of pitching required to be a starter versus being a reliever, these are significant improvements as he got older.

This level of pitching performance moves him from being a better than average starting pitcher to one of the all-time great relief pitchers. Even though he was only a closer for about 12 years, he is seventh on the all-time list in saves. The six pitchers who have more saves then he does are included in Table 2. All six of them pitched as a reliever for at least 16 years to exceed the 387 saves Eckersley accumulated in just 12 years. Because he had such good control of his pitches during this period, he walked few batters which resulted in a WHIP of 0.999. This figure is essentially equivalent to the WHIP that Mariano Rivera put up (WHIP of 1.000) over his outstanding career. Rivera also had a career ERA+ of 205 (the best ever for pitchers who pitched at least 1000 innings). This means that his average ERA over the course of his career was 49 percent (1/2.05) of the league average. Rivera’s best year in terms of ERA+ was 2008 when his ERA+ was 316. This means his ERA was 32 percent (1/3.16) of the league average that year. That’s a pretty amazing season, even for a closer who pitched just 70.2 innings total that year. But as we will see next, Eckersley had a season better than this in terms of ERA+ even though his ERA+ overall during these 12 years were not as good as Rivera’s record-setting career performance.

As great as Rivera was, he never managed the feat that Eckersley did in 1992. That year Eckersley led the majors in saves with 51, had a 1.91 ERA, a WHIP of 0.913 and an ERA+ of 195 (his ERA was 51 percent (1/1.95) of league average) in 80 innings pitched. With this outstanding performance, he was awarded both the AL Cy Young award and the AL MVP award. Only nine other pitchers have won both awards in the same year since the Cy Young award was established in 1956. And yet, from a numerical perspective, 1992 wasn’t even Eckersley’s best year. In 1990 Eckersley had 48 saves, a 0.61 ERA, a WHIP of 0.614, and an incredible ERA+ of 603 (his ERA was 17 percent (1/6.03) of league average!) in 73.1 innings. He gave up only five earned runs and walked just four batters that entire season.

It also helps to put his second half ERA+ of 136 into perspective. Two very well-known pitchers finished their careers with ERA+ marks at, or close to, 136. Christy Mathewson had a career ERA+ of exactly 136 and Cy Young finished his career at 138. Admittedly, this is not a perfect comparison because Eckersley’s overall career ERA+ is 116. But he was keeping pace with all-time greats during the latter half of his career.

As with life, athletic careers have ups and downs. Although this article highlights many of the positive aspects of Eckersley’s career, he is arguably most well-known for one of his mistakes. This is the danger of performing on the national stage: when things go poorly, everybody remembers it. In one of the most famous moments in baseball history, an injured Kirk Gibson came to bat against Eckersley in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game 1 during the 1988 World Series. Gibson hit his famous home run (and made his also famous right arm pump after rounding first base) to give the Dodgers a walk-off victory. Eckersley says he’s been asked about the pitch he threw to Gibson constantly for the past 30 years.

Conclusion

Dennis Eckersley is one of only two pure pitchers to have appeared in over 1000 games (1071 total) and to have thrown 100 complete games (he finished with exactly 100). To achieve these milestones, he needed to be effective and durable, as both a starting and relief pitcher. The skills required to meet this standard are so rare that he will likely be the last pitcher to ever do it. The purpose of this article is to make these facts known to a broader public, and to celebrate the baseball career of a man who went from being an above-average starting pitcher, to one of the best relief pitchers of all time.

DOUGLAS JORDAN is a professor at Sonoma State University in Northern California where he teaches corporate finance and investments. He’s been a SABR member since 2014 and has been contributing articles to BRJ since 2014. He runs marathons when he’s not watching or writing about baseball. You can contact him at jordand@sonoma.edu.

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks to two anonymous reviewers for taking the time to carefully read the paper and provide feedback. Their comments substantially improved the paper and corrected the omission of players who are now included in the article.

Notes

1 Portions of the career summary are taken from the SABR Baseball Biography Project; https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/98aaf620