Wade Stadium (Duluth)

This article was written by Anthony Bush

When Miles Wolff first came to Duluth, Minnesota, and saw Wade Stadium in April 1991, he envisioned it as the crown jewel in his dream to revive professional baseball in the upper Midwest. His vision may have been blurred by optimism. Author Stefan Fatsis described a stadium in disrepair: “The concrete flooring buckled, wiring was exposed, the roof leaked, holes dotted the backstop, (and) the stands were covered with pigeon dung.” It had been over 20 years since professional baseball had been played in the stadium, a relic of the Great Depression.

When Miles Wolff first came to Duluth, Minnesota, and saw Wade Stadium in April 1991, he envisioned it as the crown jewel in his dream to revive professional baseball in the upper Midwest. His vision may have been blurred by optimism. Author Stefan Fatsis described a stadium in disrepair: “The concrete flooring buckled, wiring was exposed, the roof leaked, holes dotted the backstop, (and) the stands were covered with pigeon dung.” It had been over 20 years since professional baseball had been played in the stadium, a relic of the Great Depression.

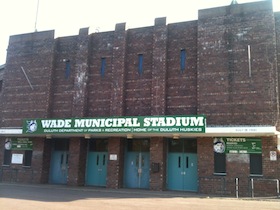

Located a half-block southeast of the 35th Avenue West/2nd Street intersection in the West Duluth neighborhood, Wade Stadium stands in the shadow of an elevated railroad leading to Duluth’s massive iron-ore docks. Merritt Creek runs near the right-field wall and the abandoned Duluth, Winnipeg & Pacific railroad line lurks beyond left field. The stadium has no luxury boxes or Jumbotron, and, unlike big-league stadiums, has no restaurants, retail stores, or hotels built nearby, eager to serve fans. And while its 12-foot-high brick walls give it the appearance of a prison, its interior offers an opportunity for liberation from the grind of modern life by stepping into the past, both Duluth’s and America’s.

Professional Baseball in Duluth

Professional baseball had flirted with Duluth before the Dukes, the Wade’s first tenants, began play in 1934. Duluth was represented by professional teams in 1886, 1887, and 1891; then in 1903 the Northern League expanded to Duluth and Wade Stadium’s predecessor, Athletic Park, was built. The Duluth White Sox played there from 1903 to 1916, primarily as a member of the Northern League. The league ceased operations on July 4, 1917, in the midst of World War I. It did not come back when the doughboys returned home after Armistice Day.

When Bruno Haas revived the Northern League for the 1933 season, he was criticized for attempting to launch a minor league during the Great Depression. His league not only survived the financial crisis, it lasted into the 1970s. Neighboring Superior, Wisconsin, fielded a Northern League team, the Superior Blues, who won the league championship in 1933. Duluth resident Richard “Rip” Wade, briefly an outfielder for the Washington Senators in 1923, managed the Blues. His father, Frank Wade, financed the team as a silent partner. When the league was expanded in 1934, the elder Wade was awarded the Duluth franchise.

The club was once again named the White Sox. In order to not be confused with the Chicago White Sox — and because it was difficult to keep the team’s literal white socks clean on the ore-dust covered field at Athletic Park — the management decided a new name was in order. The club initiated a contest in the spring of 1935 whereby fans recommended a new name for the team, and whoever suggested the winning name would receive season tickets. Over 500 people participated in the contest, proffering 170 names. John Ball and Paul Weatherby both offered “Dukes of Duluth” in honor of fellow Duluthian Thomas Hall Shastid’s 1926 novel The Duke of Duluth, which was simplified as Duluth Dukes.

From 1934 to 1940 the Dukes — affiliated with the St. Louis Cardinals — played at Athletic Park, located near where Wade Stadium stands today (its right-field corner was in roughly the same location as Wade’s left-field corner). Despite its significance as the home of the NFL’s Duluth Eskimos in the 1920s, Athletic Park was a hastily-constructed facility with uncomfortable seating, no locker rooms, and an uneven field covered with the iron ore dust that rained down from the docks.

Building the Wade

In 1938 the call went out for a new stadium to replace the dilapidated Athletic Park. A Citywide All-Sports Stadium Committee was created, and presented the city’s Charter Commission with petitions containing 7,074 signatures supporting a referendum on a $75,000 bond issue to cover the city’s share of a new stadium. In the referendum, held on November 8, 1938, more than the necessary three-fifths of the voters approved, and the vote was sustained by a recount.

After that, the Duluth City Council created a Public Stadium Advisory Committee to work with the city planning commission’s recreational committee. (One of the council’s appointees to the committee was Olaf Haugsrud, a former owner of the NFL Eskimos who later became one of the first owners of the Minnesota Vikings.)

Eschewing a plan put forth by the recreational committee to build the stadium at nearby Wheeler field, the advisory committee recommended a site adjacent to Athletic Park at 35th Avenue West. Called the “old circus grounds,” the property had been purchased by the city in 1937 for a municipal garage that was not built due to lack of funds.

The recreational committee then proposed a site exactly one block to the north, along 34th Avenue West. It cautioned against using the valuable industrial land with trackage at 35th Avenue West for a stadium. The 34th Avenue West site would have required purchasing three parcels of land: one from the state, one from the Duluth, Missabe and Iron Range Railway, and one, the Athletic Park site, from Dukes owner Frank Wade. The Stadium Committee chose the 35th Avenue West site.

A $20,000 work-relief allocation for Duluth from the State of Minnesota included $7,500 for stadium construction. Then, when plans for federal aid from the Public Works Administration fell through in the fall of 1939, the city applied for funding from another New Deal agency, the Works Project Administration (WPA). The WPA provided jobs for more than 8.5 million people nationwide from 1935 to 1943 and, in Duluth it built dozens of rustic structures and retaining walls in the city’s parks.

The WPA’s federal engineering division approved the city’s stadium plan and President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved an allotment of $80,732 on February 28, 1940. The federal project control division okayed a plan to lease the stadium to the Dukes for five years at $2,000 a year. However, the City Council postponed construction indefinitely on April 8, pending the possibility of a congressional change of WPA appropriations.

The Duluth Building and Construction Trades council, which opposed the use of WPA labor because the WPA paid less than the prevailing wage scale for skilled labor, urged further postponement. The West Duluth Business Men’s club protested the postponement, saying bonds had been sold and a majority of voters supported the plan. No congressional action was taken, and on May 3 the City Council gave the go-ahead for construction. Preliminary work commenced on May 20 after a groundbreaking ceremony. The Duluth Herald reported on July 9 that “At present two shifts of 75 men, directed by Roy Gamache, superintendent, under the supervision of C.J. Knutson, WPA engineer, are placing wall footings, doing drainage work, and grading and filling in, with construction of the walls and stands to follow.”

On August 7 the Dallavia Construction Co. won the construction contract with a low bid of $12,994. The company would lay 381,000 paving bricks salvaged from the reconstruction of nearby Grand Avenue when it was repaved in concrete earlier that summer.

Baseball legend Joe DiMaggio visited the nearly-completed stadium in January 1941 while staying with his in-laws. DiMaggio had married actress Dorothy Arnold, a Duluth native, in 1939. Joltin’ Joe waded through the snow to take a swing at an imaginary pitch and remarked, “Baby, batting out a homer in this park will be a good job for the best of ’em.”

The project needed several bailouts before anyone could start knocking out homers, however. The WPA had appropriated an additional $67,648 on December 16, 1940, and the city itself had to make sacrifices; the newspapers reported that $1,311 had been diverted from various city funds to purchase two carloads of cement. With the stadium close to completion in June 1941, another purchase of materials was necessary to prevent a work shutdown. The city purchased the materials on the assurance of Minnesota Governor Harold E. Stassen that $10,000 in legislative emergency funds would be awarded to complete all of Duluth’s major WPA public-works projects.

The First 40 Years

The Dukes played their first game at the brand-new Duluth Municipal All-Sports Stadium on July 16, 1941. While fans and players enjoyed the facility, the Dukes took it on the chin in their match with their cross-port rivals, losing to the Superior Blues 6-3.

The Northern League shut down after the 1942 season because of World War II. A short-lived but historically significant league was established in its stead. The Twin Ports League, the only Class E minor league to have ever existed, lasted six weeks in the summer of 1943 before folding on July 13. The league consisted of four teams: the Duluth Dukes, Duluth Heralds, Duluth Marine Iron, and Superior Bays. The three Duluth teams played their home games at the stadium. Most of the players were local industrial workers. The Northern League resumed play in 1946, and the Dukes were once again part of the Cardinals’ system.

On July 24, 1948, tragedy struck while the Dukes were traveling from Eau Claire, Wisconsin, to St. Cloud, Minnesota. A truck collided head-on with the team bus in Roseville, Minnesota, killing team manager (and bus driver) George “Red” Treadwell and players Don Schuckman, Gilbert Trible, and Gerald “Peanuts” Peterson. Another player, Steve Lazar, died two days later. Only four of the 13 survivors managed to continue their careers as professional baseball players.

The experience would prove difficult for Frank Wade to overcome. He sold the Dukes to Adam Pratt in 1951, but continued his role as president. Pratt sold the club to M.E. Olson and Ken Blackman in September 1952. Wade served in an advisory capacity for the new owners. He died on January 12, 1953, after suffering a heart attack. He was 80 years old. Known as Duluth’s “Mr. Baseball,” Wade spent a half-century promoting the sport in the Zenith City. His obituary in the Duluth News Tribune said that his health, “always vigorous and robust, cracked under the strain” of the 1948 bus accident.

A year later the old stadium advisory committee came together to propose that the city rename the municipal stadium in Wade’s honor, citing his work over the years: “(He) gave so freely, gladly and generously of his time, effort, and money to perpetuate the great American game of baseball and to afford so much clean, wholesome recreation and entertainment to our citizens,” the committee said. The City Council passed a resolution on February 3, 1954, and the Duluth All-Sports Municipal Stadium officially became Wade Municipal Stadium. Duluth residents would soon refer to it simply as “Wade” or “The Wade.”

Wade’s team continued to call the stadium home after his death. The team had lost its affiliation with St. Louis in 1950 and played independently until 1954, when it became part of the Cincinnati Redlegs farm system. The 1950s proved difficult for the Twin Ports to support two professional teams after the advent of television brought major-league baseball into living rooms across the nation. The Superior Blues folded after the 1955 season and merged with Duluth the following year as the Duluth-Superior White Sox, part of the Chicago system. In 1960, now as a Detroit farm team, the Dukes name returned.

Many future stars and Hall of Famers played at the Wade while members of Northern League teams. Aberdeen fielded Don Larsen, Earl Weaver, and Jim Palmer. Hank Aaron played for Eau Claire. Roger Maris got his start for Fargo-Moorhead, while Willie Stargell did the same in Grand Forks. Lou Brock, Orlando Cepeda, and Gaylord Perry all played for St. Cloud.

Duluth’s most famous connection to the major leagues was in the 1960s, when the club was affiliated with the Detroit Tigers. Twelve of the players on the Tigers’ 1968 World Series championship team had played for the Duluth-Superior Dukes, including Bill Freehan, Willie Horton, and Denny McLain.

By the end of the 1960s Duluth was once again affiliated with the Chicago White Sox after affiliations with Detroit and the Chicago Cubs, and the Dukes were thriving. They were Northern League champions in both 1969 and 1970, and attendance increased 25 percent from 1968 to 1969 and 41 percent from 1969 to 1970.

The situation was different in the majors. The White Sox’ attendance in Chicago was less than 500,000 in 1970, and the team lost $900,000. Across the board, major-league clubs were severing ties with their low-level minor-league affiliates in cost-cutting measures. By December 1970 the Dukes had lost their agreement with the White Sox and were unable to find a new parent club; Duluth dropped out. The Northern League lasted just one more season, fielding just four teams.

After the Dukes

The stadium had long offered more than just Dukes games. In 1949 it hosted the annual state high-school baseball tournament, in which Edison High School of Minneapolis defeated Washington High of St. Paul, 6-3, for the state championship. At a banquet at the Spalding Hotel in downtown Duluth, guest speaker I.T. Simley, South St. Paul’s superintendent of schools, “indicated Duluth in the future may become the high-school baseball capital of the state as Minneapolis is in basketball and St. Paul is in hockey.” But it was the only time the tournament was held in the city.

Baseball continued to be played at the Wade after the Dukes’ departure. The University of Minnesota Duluth played its home games there from 1971 to 1988 and high-school baseball continued at the Wade, but it was hardly enough to support the stadium. When Proctor High School defeated Denfeld High School of Duluth for the 1976 Section 7AA Championship, the Duluth News Tribune reported that the paid attendance of 929 was the “largest in recent years.” The two events that drew the biggest crowds to the stadium were not related to baseball. A Willie Nelson concert drew 8,200 people in 1983, and a year later the Beach Boys and Three Dog Night also performed at the Wade.

Even the efforts of Ray Adameak could do only so much in the face of years of neglect in the harsh Duluth climate. Adameak became the head groundskeeper at the Wade in 1986. He immediately put grass back in the infield that had been removed in 1974. Adameak worked to maintain the playing surface, but the structure itself fell into disrepair.

Miles Wolff’s 1991 plans for resurrecting the Northern League were solidified when he saw Wade Stadium. Wolff, former owner of the Durham Bulls and founder of Baseball America magazine, was steeped in baseball history. Author Stefan Fatsis described the moment Wolff first saw the Wade as an epiphany: “From the outside [Wolff] saw a fully enclosed brick behemoth, a structure full of mass and power, a ballpark stuck in a time capsule he had accidentally unearthed.”

Like Adameak’s work, a community “Save the Wade” task force could do only so much. Fundraising efforts included an exhibition game between the Minnesota Gophers and the Minnesota Duluth Bulldogs in 1991, but those efforts fell short. It took Wolff’s daring vision to get the City of Duluth and Mayor Gary Doty to authorize a $527,000 renovation project. The Wade was given a rebirth.

Professional baseball returned to Duluth in 1993 with a brand-new team with an old name. The Duluth-Superior Dukes played for ten seasons in the independent Northern League. Despite a league championship in 1997, they had nine losing seasons, poor attendance, and a revolving door of owners who could not turn a profit. After the 2002 season the club moved to Kansas City, Kansas, and became the T-Bones. The T-Bones left the Northern League and joined the American Association after the 2010 season.

The College of St. Scholastica started playing home games at the Wade in 2000, and as of 2013, still does. It is also the home of Duluth’s Denfeld High School baseball team and was the longtime baseball home of the city’s Central High School until 2004, when a new field was built on the school’s campus. (The school has since closed.)

While professional baseball was gone, the Duluth Huskies immediately filled the void in 2003. The Huskies compete in the Northwoods League, a summer collegiate league. In January 2012 the Huskies began working with the City of Duluth, which owns the stadium, on gathering funds for another renovation project. Among the issues: The facility’s 70-year-old brickwork needs repointing throughout the entire structure, and a portion of the wall parallel with the first-base line, which had been leaning, collapsed during a winter storm in 2013.

The $8.1 million project envisioned by the Huskies included a new entrance plaza and artificial turf. The Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development passed on the proposal in September 2012, despite approving funding for a ballpark project in St. Paul. The Huskies hoped for favorable consideration of a bonding proposal at a future session of the Minnesota legislature.

For most of his life, Frank Wade helped baseball grow in Duluth. Only time could tell if the brick landmark that bears his name would continue to be the site of many a game for years to come.

Sources

Fatsis, Stefan, Wild and Outside: How a Renegade Minor League Revived the Spirit of Baseball in America’s Heartland (New York: Walker & Company, 1996), 24.

Duluth Herald.

Duluth News Tribune.

Baseball-reference.com

College of St. Scholastica sports information.

Duluth Public Library.

University of Minnesota Duluth sports information.