Oakland Park (Jersey City, NJ)

This article was written by Bill Lamb

Days before the start of the 1889 National League season, New York Governor David Hill vetoed legislation that would have rescued the Polo Grounds from imminent demolition by New York City officials. With his club’s ballpark lost, New York Giants principal owner John B. Day activated his fallback plan. Until Day could build a new facility somewhere in Manhattan, the Giants would play their home games in vacant St. George Grounds, a Staten Island ballpark that had hosted the recently disbanded New York Metropolitans of the major league American Association during the 1886-1887 seasons. But the St. George Grounds playing field needed work before it was ready for the Giants. As a result, the Giants were obliged to play their home opener in Oakland Park, an undersized ballpark located in Jersey City.

The Giants’ temporary quarters were a short-lived playing grounds so obscure that modern-day baseball historians often misidentify it as Oakdale Park (a late-19th century ballpark located in Philadelphia).1 Any attempt to profile Oakland Park today is handicapped by the unavailability of essential information. Among other things, the physical layout and playing field dimensions of the ballpark are unknown. No photograph, ink drawing, or other image of Oakland Park exists. Even the ballpark’s street location is not entirely certain. Nevertheless, using the scanty data reposed in vintage newsprint, this essay will attempt to recall long-vanished Oakland Park.

Like Newark, Hoboken, Irvington, and various other North Jersey municipalities, Jersey City was a hotbed of the early game, with local amateur nines dating from the mid-1850s.2 Professional baseball came to town in 1885, when the Jersey City Skeeters enrolled in the minor Eastern League. Seven weeks into the campaign, however, the Skeeters were supplanted by the circuit’s Trenton franchise, relocated to Jersey City.3 The home field of the Skeeters/Trents was a local ballpark known as the Grand Street Grounds, a facility that continued to service Jersey City’s pro clubs through the 1887 season.

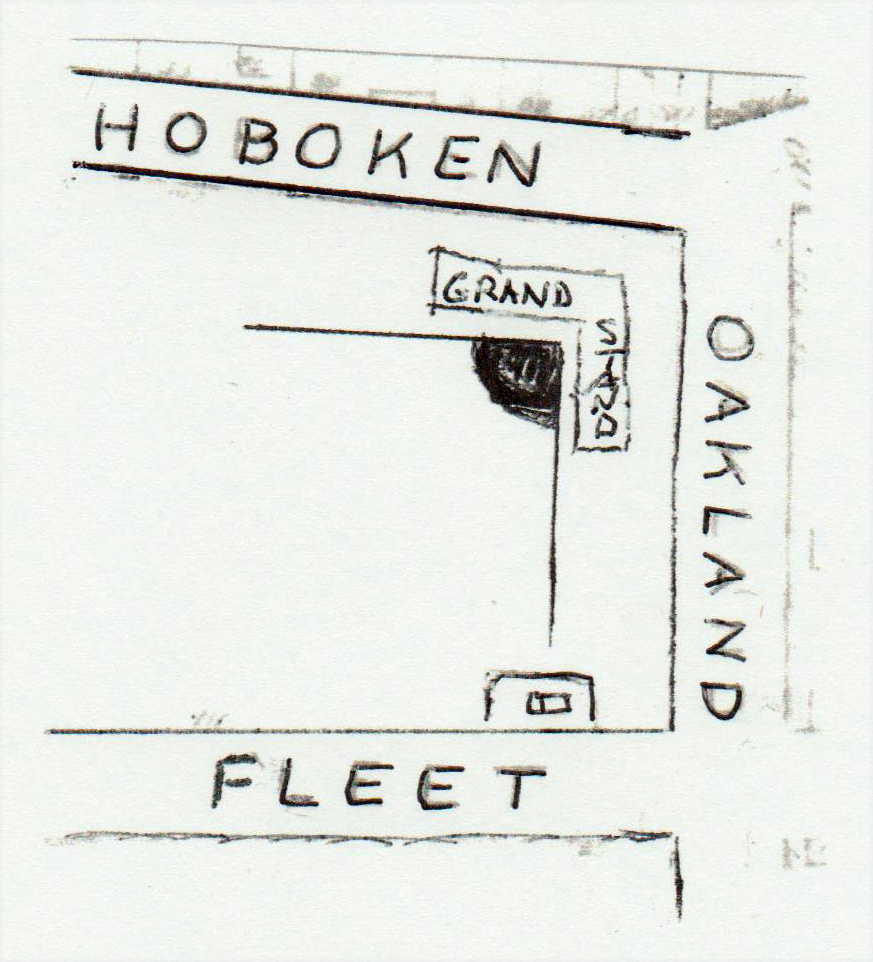

Among the grounds available to Jersey City’s thriving contingent of semipro and amateur baseball clubs was Oakland Park, situated in a tough working-class neighborhood of the sprawling Jersey City Heights district. Although there is contrary evidence, the ballpark was most likely situated on 4.63 acres bounded by Oakland Avenue, Hoboken Avenue, Fleet Street, and Bonner Street.4 Construction of the ballpark was underwritten by a group of local investors newly incorporated as the New Jersey Exhibition Company.5 The real property on which Oakland Park was built was owned by the Erie Railroad and leased by the NJEC.

Ground was broken on April 20, 1885,6 and the small wooden ballpark was ready for use in early May.7 Little description of Oakland Park appears in newsprint. All that can be said with assurance is that the grounds were entirely encased by a high board fence; that a covered grandstand of undetermined size was situated behind home plate and extended a short distance along the foul lines, and that grandstand spectators seated behind home plate were protected by wire meshing. A locker room and an office were also placed on the property.8

Oakland Park was in regular use during its first summer and often featured games between local teams for a cash purse.9 But the revenue produced by small-time baseball proved meager and the ballpark soon became a financial sinkhole for NJEC investors. In October 1885, the grounds and its improvements were advertised for sale at public auction, but ultimately escheated to the railroad, which permitted its use by local teams to continue.10 Later that month, Oakland Park received its first taste of major league baseball when the New York Giants played a postseason exhibition game against the Eastern League’s Jersey City Trents there.11

The exact timing is unclear, but the lease to Oakland Park was eventually assumed by Giants club boss John B. Day sometime in August 1888. In the meantime, the ballpark was likely operated by one Matthew Ludlow of Hoboken12 and thereafter by Fred Chapin, a Jersey City tavern and theater owner.13 Oakland Park began the 1886 season as the home ballpark of the Climax, a fast amateur team sponsored by the Lorillard Tobacco Company, one of Jersey City’s largest employers. Another Oakland Park tenant was the Hudson Colored Club of Jersey City, a Black amateur team.14 Among the features of the season’s early going was a rare interracial game between Hudson Colored and “a hastily gathered nine of white and black players.”15

With the 1886 baseball campaign heading toward its close, Oakland Park’s seating was expanded to accommodate crowds anticipated for the circus, wild west shows, and other non-athletic entertainments coming to Jersey City. In mid-September, nearly 100 patrons attending an evening performance of an Indian Village show were injured when a recent addition to the grandstand collapsed.16 One account of the incident stated that the combined new and previously built “stands had a seating capacity of 1,774 persons.”17 During the ensuing months, Oakland Park sustained further damage, being plagued by “young hoodlums…tearing down doors, seats, and fencing, and carrying them away for firewood.”18

With the Climax club having abandoned Oakland Park for the Grand Street Grounds, baseball activity slackened during 1887. The only nines regularly using the grounds were the teams of a locally stationed military regiment.19 The main park attractions that year were the circus and a horse show.20

But that changed dramatically in 1888. Over the preceding winter, the Jersey City Skeeters had transferred their affiliation from the minor league International Association to the newly organized Central League. The club also changed its home field, switching to Oakland Park. That August, title to the Jersey City team was acquired by New York Giants principal owner Day. Junior partner in the new operation was Pat Powers, the holdover field leader of the Skeeters ball club.21 By the time that the two men joined forces, improvements intended to make Oakland Park “the finest [ballpark] in the state” had already been undertaken.22

As part of his entry onto the local baseball scene, Day assumed the lease for Oakland Park.23 Guided by manager Powers, the club posted a sterling 84-25 (.771) record but lost the Central League crown by an eyelash to its archrival, the (83-23, .783) Newark Little Giants. With his New York Giants winning the National League pennant and the ensuing World Series against the AA champion St. Louis Browns, and with revenue pouring into his Metropolitan Exhibition Company’s coffers, Day stood at the pinnacle of his sporting life success in late 1888. Within a year, however, his fortune rapidly spiraled downward. And Oakland Park became an incidental casualty of Day’s misfortunes.

Likely because Day was highly esteemed and popular with fellow club owners, various major league teams booked his Oakland Park for spring 1889 exhibition games. Day himself, however, was distracted, locked in a desperate fight to save his big-league club’s ballpark from destruction by New York City officials. The Polo Grounds and the large, often unruly, crowds that attended Giants games had long been anathema to inhabitants of the tony Central Park North neighborhood of Manhattan where the ballpark had been built. In 1888, sympathetic officeholders in city government adopted a plan to redress resident complaints – by running a new street through the Polo Grounds outfield.

After his courtroom challenges to the city’s action proved unavailing, Tammany Hall stalwart Day turned to political allies in New York state government. As the 1889 baseball season drew near, a bill nullifying the condemnation of the Polo Grounds was passed in the state legislature and sent to New York Governor David Hill.24 But days before the baseball season was scheduled to begin, Hill vetoed the bill, deeming it an affront to the sovereignty of local government and the principle of home rule.25

Although bitterly disappointed by the veto, Day was not without recourse, having prudently devised a standby ballpark strategy. If the Polo Grounds were lost, Giants home games would be played in vacant St. George Grounds, the Staten Island ballpark formerly used by the by then defunct New York Metropolitans of the American Association. A $6,000 rental agreement signed by Day with St. George Grounds owner Eratus Wiman promptly cemented the Giants’ relocation.26 One obstacle still remained: the diamond in Staten Island had lain dormant during the previous baseball season and would not be in condition for play by opening day.

Agreeably for the New York Giants and John B. Day, the schedule of the newly organized minor league Atlantic Association placed its Jersey City Skeeters club on the road during the first week of the 1889 season.27 That made Oakland Park available for the Giants’ opener, but simultaneously posed “the great question [of] what to do with the crowds, as the [Oakland Park] stands can only hold so many.”28 Given that the Giants had no other playing field option, the question was largely academic.

Oakland Park entered the ranks of major league ballparks on April 24, 1889, hosting the world champion New York Giants’ season opener against the Boston Beaneaters. The New York Herald began its coverage of the contest by grousing about the transportation inconveniences endured by those making their way over from Manhattan, crammed like “sardines in a box” on Jersey City-bound ferries.29 A less critical Gotham daily approved of Oakland Park’s festive appearance, noting that “floating far above the grand stand and outfield fences were flags which, while the oncoming crank was yet far away from the grounds, caught and held his eyes.”30 As game time approached, “a steady stream of people kept the turnstiles in constant motion. The crowd soon filled the seating capacity of the grounds and overflowed upon the field.”31 With throngs turned away at the gate, official game attendance was pegged at 3,042.32

Much to the dismay of the New York faithful, the Beaneaters prevailed, 8-7. Significant for our purposes, the game’s extensive newspaper reportage was devoid of mention of Oakland Park’s playing field dimensions,33 architectural design,34 or surrounding atmospherics.35 Nor were ballpark details incorporated into coverage of minor league games played at Oakland Park – either before or after. This lends itself to the conclusion that there was nothing particularly distinctive about the grounds. Oakland Park was likely nothing other than a small-capacity but conventional late 19th century wooden ballpark.

The second and final major league game at Oakland Park was played the following day. This time, the Giants were victorious, 11-10, before a reported crowd of 1,424.36 As the day before, neither local nor national game reportage included mention of Oakland Park’s attributes. It was only identified as the site of the contest.37 Overnight rain thereupon forced the cancellation of the New York-Boston series rubber match.38 With the St. George Grounds now whipped into playing condition, the Giants swiftly moved their operations to Staten Island. Oakland Park’s time as a big-league venue had come to a close.

The following week, Oakland Park hosted the home opener of the Atlantic Association Skeeters. A reported 1,200 fans including Jersey City Mayor Orestes Cleveland were on hand to see the home side deliver a 14-5 pasting to Worcester.39 Shortly thereafter, the ballpark gates opened for play by the teams of the Hudson County Amateur League.40 And in late June, Oakland Park was the site of an open-air carnival that featured broadsword combat on horseback.41 Such attractions helped sustain the ballpark, as its primary tenant was encountering financial difficulties. In late July, Day, having “lost money on his Jersey City venture,” allowed “the club to go under.”42 Upon the folding of the Jersey City Skeeters, Day refocused his attentions on the operation of the New York Giants, and Fred Chapin reassumed day-to-day oversight of Oakland Park activity.43 The Giants club boss, however, remained the holder of the ballpark lease.

Over the winter of 1889-1890, attempts to revive Jersey City as the site of an Atlantic Association franchise were hampered by the difficulty that local club backers encountered in reaching agreement with Day on sub-letting Oakland Park.44 “The enormous price that Mr. John Day asks for the lease of Oakland Park and the grand stand” proved an “obstacle” to the proposed club’s use of the grounds.45 Day had made a fistful of money during the first eight years of his Metropolitan Exhibition Company’s existence,46 but he was now beginning to feel the financial pinch of construction of the New Polo Grounds, the Giants’ spacious new ballpark in far north Manhattan.47 Day was also obliged to marshal his monetary resources for the looming battle with Players League forces in New York. In the end, however, a deal was reached, and the newly minted Jersey City Gladiators began the 1890 season with Oakland Park as their home field.

The havoc wreaked on the baseball scene by the arrival of the Players League is beyond the scope of this essay. Suffice it to say that with five major league ballclubs,48 as well as the Newark Little Giants of the Atlantic Association, all playing within 15 miles of Jersey City, the competition for paying customers faced by the fledgling Gladiators was daunting. The Jersey City club then sealed its fate by getting off to a dismal playing start. On July 19, 1890, with a record of 27-46 (.370), the Jersey City Gladiators disbanded.49 And with that, the Oakland Park connection to Organized Baseball was irrevocably severed. From then on, activity at the ballpark was confined to semipro and amateur baseball, plus occasional soccer, football, and lacrosse matches. The circus, wild west shows, and other non-athletic amusements also used Oakland Park on a random date basis.

The absence of a professional baseball tenant quickly took its toll on the grounds. Neglected outer premises frayed and locker room pipes and fixtures were ripped out by thieves.50 But Oakland Park prospects brightened when the deep-pocketed Lorillard Athletic Club entered negotiations with Day for use of the ballpark. By that time, the New York Giants were locked in a death struggle with their local Players League rival and hemorrhaging red ink. But while Day was hard pressed for ready cash, he remained firm in his $2,000 per annum rental demand. Deeming that price exorbitant, the local press warned that Day risked having “a white elephant on [his] hands if he does not accept a fair offer, for the ground begins to show the need of a responsible party to keep it from going to ruin or being carried away piecemeal.”51

Negotiations stalled, and in late May 1891, it was reported that Oakland Park had been sub-let for five years by a different party, one Harry Powers.52 Yet less than two weeks later, it was announced that the Lorillard AC had succeeded Day as holder of the lease to Oakland Park and would be using the grounds as home field for association athletic teams.53 In its final year under Day’s control, Oakland Park had fallen into disrepair. To rectify the situation, the new lessee promptly dispatched “a large force of laborers” to renovate the property and to install a cinder track around the perimeter of the playing field. The clubhouse was enlarged, restroom facilities for event attendees were enhanced, and seating was replaced in the grandstand.54 Later, the wire mesh behind home plate was repaired and a canvas roof was extended over a bleacher section that had been added to the ball field.55

Once refurbished, Oakland Park served as the home field for the Lorillard AC baseball, soccer, lacrosse, and track and field teams. Lorillard also continued the practice of making the grounds available for local amateur clubs, as well as for the circus. Unhappily, the onset of hard economic times decimated the Lorillard AC membership, and in March 1893 the club abandoned the lease to Oakland Park.56 The property reverted to Erie Railroad control, but it is unclear how Oakland Park was managed from that point on. Amateur teams continued to have access to the grounds, but activity began to dwindle.

Beginning in early 1895, the Hudson City Improvement Authority periodically approached the railroad about acquiring Oakland Park. Erie was willing to lease the grounds for up to 25 years but declined to sell the property.57 Negotiations continued but eventually foundered as it became clear that expending funds on the acquisition of parkland was not a priority of Jersey City political leaders.58

As the 19th century trickled to a close, so did activity at Oakland Park. The last discovered event taking place there was a baseball game between two local youth clubs played in early September 1899.59 Oakland Park lay dormant at the time that Jersey City reentered Organized Baseball with a short-lived entry in the 1900 Atlantic League. The new club used the Johnston Avenue Grounds instead.60 Early in 1906, the Erie Railroad sold the ballpark property to the National Realty Company of Jersey City, which promptly subdivided it into building lots.61 All remaining trace of Oakland Park soon vanished.

More than a century after Oakland Park saw its last athletic activity, the tough Jersey City Heights neighborhood where it once sat has undergone transformation. Today, the old ballpark property provides addresses for a dense mix of modern commercial and residential buildings. Beyond living memory and without any token of commemoration, Oakland Park, the undersized local grounds that hosted the 1889 season-opening game of the world champion New York Giants, is long forgotten.

Acknowledgments

The writer is indebted to John Beekman, chief librarian at the Jersey City Public Library, for his assistance in the research of this essay, which was reviewed by Rory Costello and David H. Lippman and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo.

Sources

Specific sources for the information imparted above are cited in the endnotes. Generally consulted was The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson & Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 3d ed. 2007), and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 See e.g., Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Company, 2d ed., 2006), 108. Full disclosure: The writer has made the same mistake.

2 For more on the early baseball scene in Jersey City, see John G. Zinn, “Pioneer Base Ball Club of Jersey City” and “Excelsior Base Ball Club of Jersey City” in Base Ball Founders: The Clubs, Players and Cities of the Northeast That Established the Game, Peter Morris, William J. Ryczek, Jan Finkel, Leonard Levin, and Richard Malatzky, eds. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013), 194-198.

3 See “Their Last Inning: The Jersey Citys Disbanded – The Trentons Transferred to This City,” Jersey City Argus, June 24, 1885: 1. See also, “Patrick T. Powers, Promoter of Sports,” (Jersey City) Evening Journal, November 19, 1898: 27.

4 The writer’s imagining of Oakland Park’s location and layout is reflected in the crude street grid diagram that accompanies this essay.

5 Per “Sporting Notes,” (Jersey City) Sunday Tattler, April 5, 1885: 3. The corporation president was local investor Robert E. McDermott.

6 See “Another Base Ball Park,” Evening Journal, April 20, 1885: 1.

7 The scheduled May 2 ballpark opener had to be postponed “owing to the bad condition of the grounds.” Sunday Tattler, May 3, 1885: 3. The first discovered game played at Oakland Park took place on May 13, 1885, when the amateur Oaklands defeated the Marions, 5-4. Sunday Tattler, May 17, 1885: 3.

8 Details about Oakland Park were extracted from random Jersey City newspaper articles. See e.g., “Ten Persons Injured,” Sunday Tattler, September 12, 1886: 2.

9 See e.g., “Sporting Notes,” Jersey City Herald, August 1, 1885: 1, promoting a game between the amateur Jerseys and the semipro Jersey Blues, with a $250 stake going to the winner.

10 See “A Miserable Failure,” Sunday Tattler, October 11, 1885: 3.

11 As reported in “The Waning Baseball Season,” Jersey City Argus, October 22, 1885: 4.

12 Ludlow bought NJEC honcho McDermott’s interest in the corporation in September 1885. See “Personal,” Sunday Tattler, September 13, 1885: 2.

13 “Sporting Notes: Base Ball,” Evening Journal, August 12, 1886: 2: “Fred Chapin has taken charge of Oakland Park, and has put the ground in good condition for ball playing.”

14 “Base Ball Notes,” Evening Journal, May 13, 1886: 2.

15 “A Mixed Game,” Evening Journal, May 22, 1886: 3. The mixed-race nine was recruited after the advertised opposition, “the Mabies, a colored club of Englewood,” New Jersey, failed to show up.

16 See “The World’s News in Brief, “Bayonne (New Jersey) Times, September 16, 1886: 2.

17 “A Horrible Crash,” Evening Journal, September 13, 1886: 1.

18 “Boys Destroying Oakland Park,” Evening Journal, November 6, 1886: 1. The vandals “were pounced upon” by ballpark proprietor Chapin and sent to juvenile detention by a city magistrate.

19 See “Military Notes,” (Jersey City) Sunday Morning News, July 17, 1887: 5.

20 As reflected in advertisements published in the Sunday Morning News, April 24, 1887: 5, and July 3, 1887: 4.

21 Per “Patrick T. Powers,” above. The New York Giants franchise was officially owned by the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, Day’s corporate alter ego.

22 As reported in “Base Ball,” (Hoboken, New Jersey) Hudson County Democrat-Advertiser, April 21, 1888: 2.

23 Coverage of an early May exhibition game between the Skeeters and the NL Philadelphia Quakers at Oakland Park appeared in “Jersey City Wins,” New York Evening World, May 4, 1888: 1. Periodic advertisements for 1888 Jersey City home games at Oakland Park were also published in The Sporting Times.

24 As reported in “The State Legislature,” New York Sun, April 20, 1889: 3; “Day Hears of It,” New York Evening World, April 19, 1889: 1; and elsewhere.

25 See “Goodby, Polo Ground!” New York Tribune, April 24, 1889: 10; “It Is Vetoed,” New York Evening World, April 23, 1889: 1.

26 As reported in “Foley Looks Over Field,” Boston Herald, April 22, 1889: 3; “Abandoning the Polo Grounds,” New York Tribune, April 19, 1889: 3; and elsewhere. Three years earlier, Wiman had purchased the New York Mets franchise from the Day-controlled Metropolitan Exhibition Company and initiated the ill-fated relocation of the club to Staten Island.

27 Over the winter, the Central League was re-formed as the Atlantic Association.

28 “Baseball Notes,” Jersey City News, April 24, 1889: 1.

29 “Boston Gets First Blood,” New York Herald, April 25, 1889: 10.

30 “Losers,” New York Evening World, April 24, 1889: 1. The three banners commemorated the 1888 New York Giants National League pennant, World Series victory, and triumph over the AA Brooklyn Bridegrooms for the New York metropolitan area championship.

31 Same as above.

32 As noted in “Contest Begun,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Daily Herald, April 25, 1889: 1; “The Champions Defeated,” Philadelphia Times, April 25, 1889: 2; and elsewhere. A disapproving Manhattan sportswriter sniffed that “they would have had 15,000 at the Polo Grounds.” George E. Stackhouse, “Manhattan Cocktails,” Sporting Life, May 1, 1889: 3.

33 Like the short-porch left field fence at Lakeshore Park in Chicago.

34 Like the elegant façade and grandstand at Brooklyn’s Eastern Park.

35 Like the factory smokestack soot and the city dump stench that pervaded Metropolitan Park in Manhattan.

36 Per the game box score published in the New York Tribune, Trenton Evening Times, and elsewhere, April 26, 1889.

37 See e.g., “Hardie Bats Very Hard,” Jersey City News, April 26, 1889: 3; “All Right,” New York Evening World, April 26, 1889: 1 (local); “New York 11, Boston 10,” New Orleans Times-Democrat, April 26, 1889: 2; “National League Games,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 1889: 6 (national).

38 See “They Will Play on Monday,” Jersey City News, April 27, 1889: 2; “Local Ball Games Postponed,” New York Evening World, April 26, 1889: 1.

39 Per “The Atlantic Association,” New York Sun, April 30, 1889: 8.

40 “Diamond Dust,” Jersey City News, May 3, 1889: 3.

41 As reported in “A Great Show at Oakland Park,” Jersey City News, June 26, 1889: 3.

42 “Our Ball Club Must Go,” Jersey Evening Journal, July 27, 1889: 4. The Jersey City Skeeters disbanded on July 25, 1889.

43 Per “Miscellaneous Sporting Gossip,” Jersey City News, August 5, 1889: 1.

44 Backers of the new club had recently organized as the Jersey City Baseball and Exhibition Company. See “The New Baseball Club,” Jersey City News, January 30, 1890: 1.

45 “Baltimore at the Bat,” Jersey City Sunday Morning News, December 1, 1889: 9. See also, “That Baseball Team,” Jersey City News, January 13, 1890: 3; “Baseball in This City,” Jersey City News, December 2, 1889: 3; and “Gossip of the Meeting,” New York Sun, November 12, 1889: 4.

46 In 1889, it was reported that the Metropolitan Exhibition Company had cleared a staggering $750,000 profit from the operation of its ball clubs. See “An Offer for the Giants,” New York Times, September 6, 1889: 3. The figure is outlandish as the NY Giants never reported a single-season profit in excess of $35,000 while the NY Metropolitans actually lost money for the MEC. Nevertheless, Day and his corporate cohorts had done very well financially.

47 The Giants abandoned the St. George Grounds as soon as the New Polo Grounds was built and played their first game there on July 8, 1889.

48 The major league clubs close by Jersey City were the (Real) New York Giants and Brooklyn Bridegrooms of the National League; (Big) New York Giants and Brooklyn Ward Wonders of the Players League; and Brooklyn Gladiators of the American Association.

49 As reported in “Ready to Bid It Good Bye,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Daily Patriot, July 19, 1890: 1; “Jersey City to Go Under,” Baltimore Sun, July 18, 1890, S1; and elsewhere. Jersey City’s place in the Atlantic Association was promptly assumed by the Harrisburg Athletics of the recently-deceased Inter-State League.

50 See “Caught the Thief,” Jersey City News, September 22, 1890: 1

51 “Want Oakland Park,” Jersey City News, September 26, 1890: 3.

52 “The World of Sport,” Jersey Evening Journal, May 29, 1891: 3. The new lessee was not related to former Jersey City Skeeters manager Pat Powers.

53 “The World of Sport: The Lorillards Have Secured a Lease of Oakland Park,” Jersey Evening Journal, June 11, 1891: 3.

54 “Athletic,” Jersey Evening Journal, June 29, 1891: 3.

55 “Athletic,” Jersey Evening Journal, July 27, 1891: 3. The property was officially retitled the Lorillard Athletic Grounds, but the new name never took.

56 “World of Sport: Athletic,” Jersey Evening Journal, March 1893: 3.

57 See “A Park for the Fourth District,” Jersey City News, February 21, 1895: 3; “A New Park Bill,” Jersey Evening Journal, February 21, 1895: 1.

58 See “Citizen Managers,” Jersey Evening Journal, March 21, 1896: 4.

59 Per “Games of Baseball,” Jersey Evening Journal, September 1, 1899: 6.

60 The Jersey City club folded five weeks into the season. The Atlantic League followed suit two weeks later.

61 Per “Big Boom in Lower Jersey City Section,” (Hoboken, New Jersey) Observer of Hudson County, March 27, 1907: 12.