St. George Grounds (Staten Island, NY)

This article was written by Larry DeFillipo

St. George Grounds began as a paradise, created alongside the Brooklyn Bridge and the Statue of Liberty, in what became the city that never sleeps.1 The centerpiece of developer Erastus Wiman’s resort on the northeast prow of Staten Island, New York, the Grounds were, variously, the last home of the American Association Metropolitans, the setting for a pair of the most extravagant open-air theatre productions ever staged, and a seven-week bivouac for the National League Giants. “The handsomest of its kind” when it opened,2 St. George Grounds soon disappeared without a trace, turned into a rail yard and later paved to put up a parking lot.

St. George Grounds is often misidentified as St. George Cricket Grounds, akin to calling Yankee Stadium the Lumberyard. A local cricket club was the previous occupant of the parkland where Wiman built his Grounds, just as lumber previously filled the lot where Babe] Ruth built his House.3 Further complicating the Grounds’ lineage, that cricket club was not the St. George Cricket Club, but rather the Staten Island Cricket Club. The St. George Cricket Club was located in Manhattan.

St. George Grounds was built on a parcel of land previously known as Camp Washington, a name first applied to the site of an encampment of New York militia and National Guard units dispatched there in 1858 to prevent the spread of a local uprising prompted by an outbreak of yellow fever.4 The following year, baseball was being played there.5 During the Civil War, Camp Washington was a Union Army training and mustering site for several regiments, including the famed 5th New York Infantry, known as Duryée’s Zouaves.6

Jacob Vanderbilt, scion of the wealthy Vanderbilt family, owned Camp Washington until a deadly 1871 accident aboard his Westfield II ferry pushed his holdings into foreclosure. He sold Camp Washington, along with surrounding undeveloped land,7 to financier George Law, who leased some of his land to the Staten Island Cricket Club.8

Mary Outerbridge, the daughter of one of the cricket club’s founders, is reputed to have set up the first U.S. tennis court at Camp Washington following a trip to Bermuda in 1874.9 The first American tennis tournament was reportedly held at the Camp in August 1877, with the first national tournament held there in September 1880.10

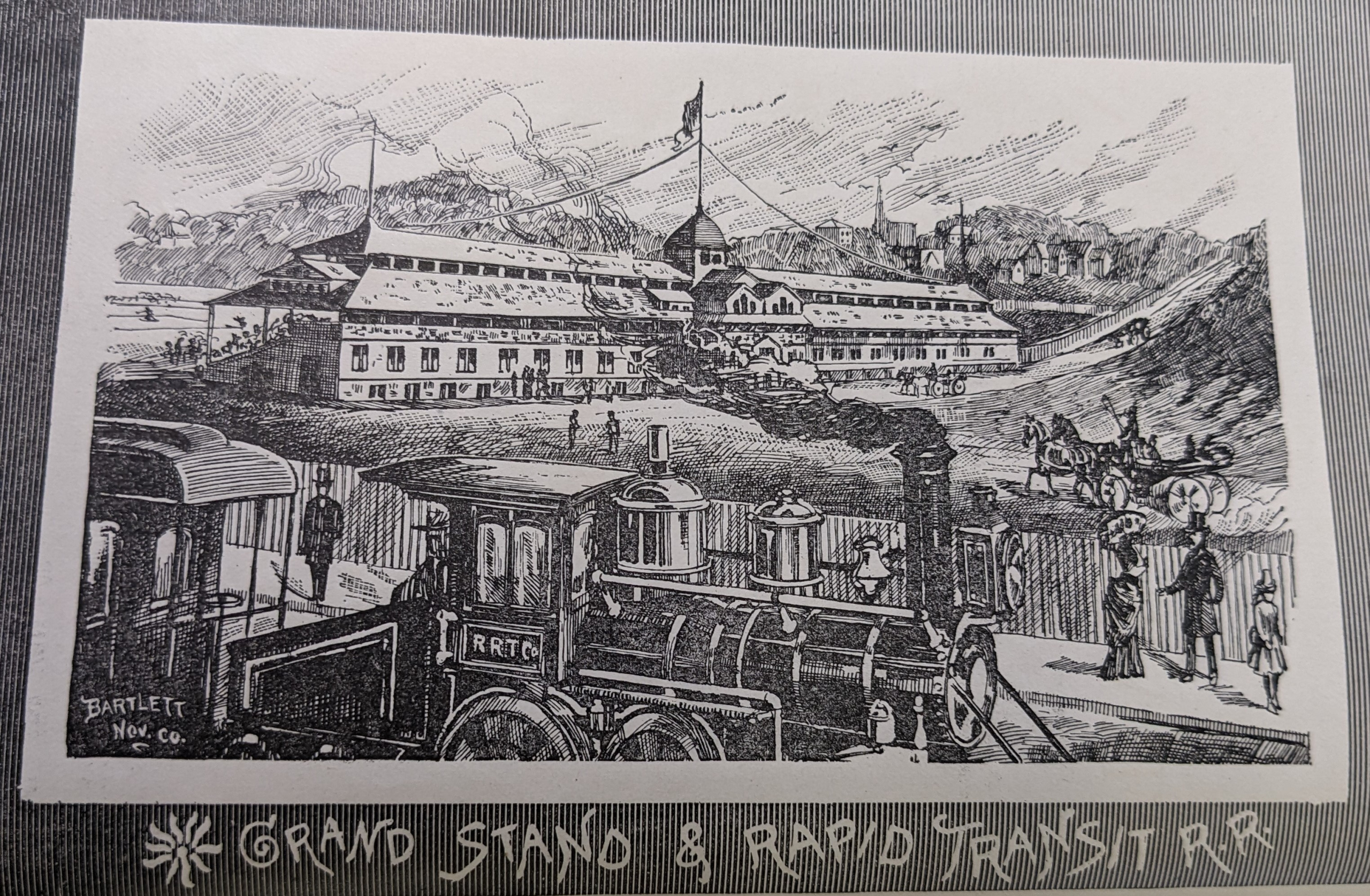

In 1880, Canadian-born businessman Wiman burst onto the scene. Stationed in New York City shortly after the Civil War, he envisioned Staten Island as a transportation hub for goods coming into the cities surrounding New York harbor. Considering its ample parklands and sweeping harbor views, he also saw the island as an amusement and entertainment destination for all of metropolitan New York. 11 He proposed the construction of rail lines running the length of both the northern and eastern shores, and a consolidated ferry service at their junction.12 By the summer of 1884, Wiman’s Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad Company had gained control of the Staten Island railroad and purchased both franchise and wharf privileges for the Staten Island and Bay Ridge (Brooklyn) ferries.13 In addition, he bought Camp Washington from George Law’s heirs,14 unveiled a plan to build a resort there, 15 then set about getting a drawing card to fill it.16

In late 1885, Wiman secured his marquee attraction. Or so he thought. He reached agreement with John B. Day to purchase the AA’s New York Metropolitans franchise and obtained the league owners’ approval to relocate the club to Staten Island.17 Soon after, league owners reversed course and cancelled Wiman’s franchise, fearing losses from lower Staten Island gate receipts as compared with a New York City venue. For good measure, they also scattered his players to other AA teams.18 After Wiman secured a court injunction, the other owners relentedand returned his players.19 Wiman set about building his team a ballpark.

By March 1886, a “small army of masons and carpenters” was erecting a wooden, two-deck (gallery) racetrack grandstand on a seven-acre parcel of land now known as St. George Grounds.20 Designed by Staten Island architect Edward L. Woodruff,21 the more than 300-foot-long grandstand consisted of a 72-foot-high center section and two adjoining wings, oriented perpendicular to the shoreline. The playing diamond was aligned so that the path between home plate and the pitcher was perpendicular to the grandstand, which provided splendid views from every seat. The structure included “outlines . . . in the Queen Anne style,”22 with a flat roofline embellished by a center cupola and squat pyramidal towers at either end.

The lower (main) gallery included 2,600 seats divided by 12 aisles, with a field-level walkway at its front. A 12-foot-wide promenade behind the gallery offered “unobstructed views of the entire [Upper] Bay, Narrows, Sandy Hook (New Jersey), Coney Island and the cities of New York, Brooklyn, and Jersey City.”23 The upper gallery had room for 1,500 spectators, with a glass-walled ladies refreshment room. The grandstand’s eastern end contained a wine cellar and a dining room with a view of the playing field. The reported size of the dining room varied, with the New York Times calling it nearly 50 feet by 140 feet, while a later Philadelphia Inquirer story claimed it was 50 feet by 200 feet, with room for 1,000. 24 The grandstand’s western wing, built into the gently graded slope, included a bar and an ice cream parlor.25 The New York Times called the grandstand “mammoth,” “larger by far than any one ever placed on a baseball field.”26

While the grandstand was taking shape, Wiman’s St. George ferry terminal opened.27 Adjacent to the Grounds’ southern edge,28 it completed the transportation network that he counted on to bring customers to his resort.

The Metropolitans played their first game at St. George Grounds on Thursday, April 22, 1886, against the Athletics of Philadelphia,29 a week into the season. The Philadelphia Inquirer estimated nearly 4,000 in the inaugural crowd,30 while Amusement Company general manager Major Williams claimed 7,000, as reported by the New York Tribune.31

The Mets, as they were often called,32 wore their eye-catching new uniforms: white shirts adorned with a distinctive blue and white polka dot necktie atop white pants with matching blue belt and stockings.33 Sartorial splendor wasn’t enough, as the Mets lost, 7-6, on a walk-off single by Athletics captain Harry Stovey.34

Further up the harbor that day, the final granite capstone was installed on the Bedloe’s Island pedestal for Liberty Enlightening the World, the gift from France that became the Statue of Liberty.35 St. George Grounds spectators and players alike would see the colossus rise over the course of the next few months.

Opening day reviews for the Grounds were mixed. The New York Times reported clear views from the grandstand’s first row to its last.36 Harper’s Weekly called the field too small to “permit of really heavy batting without danger of the ball’s going over the fence.”37 The New York Tribune ominously noted that the crowd had considerable trouble in reaching the island and just as much getting back.38 Later, the Chicago Tribune reported that it cost Wiman $51,000 “to make the greatest baseball grounds that the world had ever seen.”39

The next day the Mets lost their second game at the Grounds, a 14-6 pasting from the Athletics, with a “considerable decrease in attendance,” estimated at 2,000 by the New York Tribune.40

On May 4, the first home run hit at the Grounds came off the bat of Baltimore Orioles light-hitting second baseman Joe Farrell41 After losing their first six home games, the Mets notched their first St. George Grounds win on May 6, courtesy of a Jack Lynch one-hitter over the Athletics.42 Mets slugger Dave Orr delivered the Mets first home run at the Grounds exactly one month after it opened, a two-run shot off future Hall of Famer Pud Galvin.43

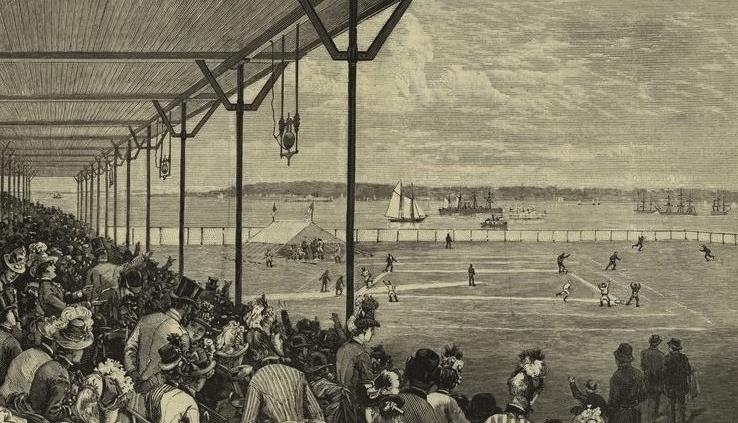

No photographs survive of St. George Grounds, but a Harper’s Weekly sketch published on May 15, 1886, provides details not found elsewhere.44 The field is enclosed with a low fence, supported by posts every few yards.45 (Though not evident in the sketch, the field sloped sharply down past third base into left field.46) Three concentric basepaths are shown, the outer pair possibly marking runners’ boundaries. A large tent is staked in foul territory aside the infield, providing cover for players not on the field. Hanging from the rafters above the well-dressed crowd are several large gas lamps, located near the front edge of the grandstand roof.47

By May 16, the Mets were 5-12 and in last place. Before the day was over, second-year manager Jim Gifford was replaced by veteran player, manager, umpire and the major leagues’ first switch-hitter, Bob Ferguson.48 After treading water for a few weeks, a two-hit shutout by Lynch in front of a packed house in St. George triggered an 8-1 Mets hot streak that pulled the club up to sixth place.49

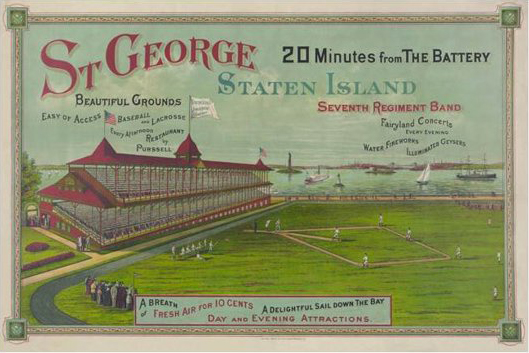

In late June, the Grounds’ new electrical fountains were unveiled, reportedly costing Wiman $40,000.50 The fountains contained 300,000 gallons of water, feeding 15 jets colored by individual 8,000 candle-power electric lights, with the jets forming a plume 150 feet high that was “plainly” visible from the southern tip of Manhattan.51 Soon after the fountains were in place, the Staten Island Amusement Company released a color poster, which promised a delightful sail down the bay to a variety of Grounds attractions, including nightly “fairyland concerts,” fireworks, and illuminated geysers, “just 20 minutes from the Battery.” 52

When the Mets were away on road trips that summer, the Grounds hosted concerts, light shows, lacrosse matches,53 amateur baseball matches, tours through a replica Japanese village and the opening of its casino.54 A fawning New York Times reported how delighted patrons filled “Wiman’s lamp-lit plaisance,” “finding the new resort in the full bloom of youth and beauty,” with a “wide expanse of green lawn suggesting pastoral enjoyment of the most civilized order.”55 For those seeking something less refined during the summer of 1886, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show could be seen at Wiman’s Erastina estate, several miles west of the Grounds. 56

In August 1886, Wiman’s pleasure palace inspired the Athletics to announce construction was underway on a new ballpark in Philadelphia “to rival the St. George Grounds.”57 Eight months later, the original Baker Bowl opened. Not all the attention that St. George Grounds garnered from rival cities was positive, however. The Chicago Tribune noted fewer than 400 spectators attended one contest and shared the opinion of unnamed others that Wiman’s venture was a financial failure.58 The Sporting News of St. Louis said the Grounds were “doomed to be a failure” because of the transportation challenges they presented.59

The opinions of pundits aside, the Metropolitans found the Grounds benefited their performance. Finishing the season in seventh place, they were 30-33-2 (.477) at home, significantly better than their 23-49 (.319) record away from the Grounds. On October 28, all of New York celebrated the dedication of the now-completed Statue of Liberty, followed by a parade through Manhattan’s financial district that became the first ticker tape parade in New York history.60

In the off-season, the possibility of night baseball at the Grounds was explored by Edward H. Johnson, president of the Edison Electric Light Company, who conducted experiments with the Grounds’ electric fountains. After finding that an illuminated ball “glistened like a meteor,” 61 he devised a scheme for lighting the entire field from bulbs buried in foul territory. Thomas Edison concurred,62 but the plan was never implemented.

Hopes were high for the Metropolitans’ 1887 season, as they welcomed former Met Dude Esterbrook back from the Giants and added promising rookie outfielder Darby O’Brien.63 After losing all 10 games of a season-opening road trip, the Mets won their May 3 home opener against the Brooklyn Grays. The game drew about 3,000 spectators who were treated to strong pitching and timely hitting from Mets hurler Al Mays and a frightening ninth-inning collision when Mets baserunner Bill Holbert kneed second baseman Bill McClellan in the face during a slide, knocking him “insensible.”64

The Mets played one more home game, then left on an 18-game road trip. While they were away, “Giants manager Jim] Mutrie’s Columbia nine” faced off against Yale University at the Grounds. 65 The Lions could do nothing with the “swift pitching” of third-year Yalie and future football coaching legend, Amos Alonzo Stagg.

By the time the Mets returned home at the end of May, they were 6-24 and in last place.66 Manager Ferguson was released, captain Dave Orr became interim manager, and ten days later former sportswriter and league co-founder Ollie Caylor was hired to take the reins. In the midst of these changes, the Mets began sharing the Grounds with the theatre production of The Fall of Babylon.67

Produced by renowned theatrical promoter Imre Kiralfy, The Fall of Babylon was a lavish, open-air re-creation of biblical events that entailed fireballs, catapults, five train cars of sets, elephants, camels, donkeys, rhinoceroses, kangaroos, an opera chorus, 170 arc lights, and over 1,000 actors and dancing girls on a 450- by-250-foot stage.68 Kiralfy called it “the grandest production that has ever been accomplished in any part of the world.”69

By mid-June, much of The Fall’s stage was in place, stretching from center field across to right field. Its effect on games was immediate and comical. During a June 13 Mets loss, the visiting Cincinnati Red Stockings’ batters “shot the ball against this stage, dropped it on top, and drove it over the top until it became a question of how long they could stand the fun.”70 Eight days later, St. George Grounds hosted a celebration of Queen Victoria’s 50 years on the British throne. Revelers enjoyed fireworks and music but left the diamond unplayable, forcing the next day’s Mets-Athletics game to be played at the Polo Grounds. Rain halted that contest after three innings.71

An estimated 10,000 fans attended the Metropolitans’ June 25 contest with Brooklyn the afternoon before The Fall’s premiere.72 Beginning with that game, the Mets instituted ground rules to accommodate the stage, limiting batters to one base for any hit to right field and two for hits to center. Excitement over The Fall seemingly juiced the Mets’ bats as well as their attendance. The afternoon before the play’s first rehearsal, the diminutive and devout Paul Radford had the only multi-homer game the Grounds would ever witness,73 and the day before The Fall’s premiere, Dave Orr launched the “longest homer ever made on St. George Grounds,” clearing the railroad tracks that ran past left field.74

Performances of The Fall continued daily in good weather through mid-September, averaging over 14,000 spectators filling the grandstand and terraced “benches” (temporary stands) on the east and west sides of the diamond.75 The Mets played 43 home games while sharing the Grounds with The Fall, going 20-21-2 over that span. One of those wins was an August 12 forfeit win over the Athletics, who refused to comply with umpire Ted Sullivan’s interpretation of the two-base rule on a ball hit by Philadelphia’s Gus Weyhing into a Babylonian diorama.76

By closing night of The Fall, the Mets were 37-76, 47 games back in the AA standings. After being trampled by 700,000 or more spectators over the past three months, the Grounds hosted Met doubleheaders the next two days. Then, the Mets agreed to move their next two home games to Philadelphia, ostensibly to reduce travel for the Baltimore and Brooklyn nines, but just as likely to give the Grounds lawn some time to recover.77

On October 7, just days before the end of the season, Erastus Wiman sold the Metropolitans to Charles Byrne, owner of the Brooklyn Grays.78 Byrne made it clear that if the franchise was to remain in New York, it would not be playing on Staten Island. The Mets ended their time at the Grounds (and their time as a franchise) with a dreary October 10 performance, whitewashed 4-0 by Baltimore’s 21-year-old phenom, Matt Kilroy, for his league-leading 46th win of the season.

The Metropolitans franchise folded after the 1887 season, with its most talented players retained by Byrne’s Grays. This was, ironically, just what Wiman had fought so hard to prevent when he bought the club.79

The Grounds were little used through April 1888, while owner Wiman tended to other matters, including overseeing the launch of his ferryboat, the Erastus Wiman.80 That summer, Kiralfy staged another open-air spectacle at the Grounds, titled Nero; or, the Fall of Rome. Featuring lions, tigers, chariot races, gladiator contests, and 2,000 performers, including 1,000 dancers and a 500-voice chorus, Nero was bigger and bolder than The Fall of Babylon.81 Prior to opening night, famed French daredevil Charles Blondin performed a highwire act on a tightrope hung between the grandstand’s upper gallery and the Nero set.82 Performed before up to 20,000 on some nights,83 the production weathered a mock stabbing that turned frighteningly real,84 and a real fire that threatened to burn the mock Rome.85 In August, four pairs of Nero cast members were married, “on stage in full view of the audience.”86

Despite the crowds, Wiman’s Amusement Company was reported to have lost $8,000 on Nero, with little prospect of turning a profit on future-year productions for which they were under contract.87

In early 1889, as the reigning NL (and World’s) Champion New York Giants were fighting to hold back city plans to build a street through the heart of their Polo Grounds field in upper Manhattan, the possibility of the Giants moving to St. George Grounds was floated in the press.88

Once a last-ditch legislative effort to quash the street extension went nowhere in mid-April 1889, Giants owner John Day announced that the Giants would relocate to St. George.89 “I doubt very much whether we would go back [to the Polo Grounds],” he said, but it “would depend largely on how we like St. George.” Despite concerns about the inclined outfield at the Grounds, and the diamond’s overall condition, the New York Tribune called the Grounds “undoubtedly the handsomest in the country,” with “superior accommodations to those of any other ball ground.”90

The Giants’ initial experience with the Grounds was dreadful. After playing their first two home games in Jersey City, the Giants had to cancel their first scheduled game at the Grounds due to rain. Despite the work of “numerous gangs of men and horses,” the field couldn’t be made ready by the next day, forcing a second cancellation.91 The New York Sun decried that the beautiful diamond was gone, replaced by acres of mud and water. Left field had been excavated to a depth of ten feet, to serve as an orchestra pit for Nero, with the removed earth piled in center. The outfield was half covered with boards, necessitating outfielders wear rubber-soled shoes to play on them.92

A crowd of 3,795 attended the Giants’ first game at St. George Grounds on April 29. Before the first pitch, they were treated to the spectacle of 100 workers removing towering structures left behind from the Nero production.93 Once the half-earth/half-stage diamond was made playable, the Giants defeated Hank O’Day and the Washington Nationals, 4-2, on pair of ninth-inning home runs. 94 After second baseman Art Whitney hit a ball that landed on the stage and bounced over the fence, umpire McQuade [sic]95 declared it a home run as the Giants had no ground rules for balls striking the stage.96 Ed “Cannonball” Crane followed with a no-doubter, driven over the left field fence and into the water.

Visiting NL players hated playing at the Grounds. Pittsburgh Pirate (and future evangelist) Billy Sunday complained of having to “wade through mud in making a run” on the largely un-sodded field, calling it “wretched,” and “the worst in the league.”97 “Players will have to devote more time to killing mosquitoes than playing ball,” said the Sunday Philadelphia Item.98 Chicago lost a game because one of their outfielders fell on the stage attempting to catch a fly ball at a crucial spot late in a game.99

The Giants maintained a solid record at the Grounds (17-6 through mid-June), but were drawing under 2,500 fans per game on a lumpy and pock-marked field that the New York Sun was now calling the worst ever.100 On June 14, with under 2,000 fans in attendance, the Giants drubbed the Philadelphia Athletics, 14-4, behind “Smiling” Mickey Welch.101 After bad weather cost the Giants the large gate receipts expected in their next two games,102 Day realized that staying in St. George had become unworkable. The continuing loss of revenue to the Brooklyn Grays and transportation challenges for players and fans could only be overcome by moving back across the harbor. 103 Once the Giants left for a three-week road trip, Day leased a large lot in upper Manhattan and had a new Polo Grounds hastily built. When the Giants returned, they bid adieu to St. George Grounds, and moved into their new home.104

Over the next few years, the Grounds were home to low-key local events and extravaganzas planned that never were.105 Giants manager Jim Mutrie, now a Staten Island resident, organized a testimonial on the Grounds to reigning bare-knuckle heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan, expecting up to 40,000 spectators for an event that never happened.106 Later, the casino hosted a meeting to organize support of a proposal by Wiman to have Staten Island selected as the centerpiece of New York’s bid for the World’s Fair of 1892.107

Indebtedness of $1 million and impending bankruptcy forced Wiman to sell his St. George real estate holdings in 1893, held in his wife’s name.108 By 1898, the grandstand was gone, and the Grounds had been converted to a rail yard for the SIRT’s parent company, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. 109 In the early 1950s, a portion of that rail yard became a parking lot for the Staten Island Ferry terminal.110 The parking lot was removed in 2015 to make way for Empire Outlets, a retail shopping complex considered the largest development project on Staten Island since the construction of the Verrazano Narrows bridge in the 1960s.111

Several 21st century sources refer to St. George Grounds as Mutrie’s Dump or Mutrie’s Dumping Grounds. 112 Those terms more properly apply to Manhattan’s Metropolitan Park, which Mutrie’s Metropolitans called home for five weeks in the spring of their 1884 championship season. That ballpark, bordered by the Harlem River in upper Manhattan, was built on the site of a former city dump, with a playing field composed of landfill refuse.113

Eleven major league players debuted at St. George Grounds, most notably the Mets’ Fred Mauer. Under the assumed name of Harry Brooks, the amateur Mauer was the Mets’ starting pitcher on July 24, 1886, against the Louisville Colonels. He allowed nine runs in the first inning, another four in the second inning, then was shifted to center field, where he committed four errors. Starting left fielder James Roseman pitched the final seven innings for the Mets.114

More than a decade after St. George Grounds disappeared, it served as the setting for one of the most fanciful stories told by Al Spink in his ground-breaking history of baseball, The National Game. Spink describes how Jimmy Ryan of the NL Chicago White Stockings hit a ball over the center field fence that, unbeknownst to all, struck a passenger onboard a ship bound for England. Ryan, he claimed, received the ball back by mail from Liverpool, proving he had the record for the longest hit ever.115

Author’s Note

The author attended high school a short walk from both the former St. George Grounds and the St. George Ferry terminal. From a top floor classroom, he could see two new under-construction icons reach for the sky, nearly 90 years after Lady Liberty first did: the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. Some 30 years later he unwittingly parked in the lot where St. George Grounds once stood before taking his family to see the New York Metropolitans of the modern era play at another ballpark now gone as well, Shea Stadium.

Acknowledgments

This article was reviewed by Kurt Blumenau and Howard Rosenberg and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

Sources

In addition to the sources referenced below, the author relied heavily on the author’s SABR Games Project story on the inaugural Metropolitans game at St. George Grounds, Bill Lamb’s SABR biographies of Erastus Wiman and John B. Day, Staten Island native Peter Mancuso’s biography of Jim Mutrie, Brian McKenna’s biography of Bob Ferguson, David Nemec’s biography of Ollie Caylor, Stew Thornley’s biography of the Polo Grounds and Larry Lupo’s When the Mets Played Baseball on Staten Island (New York: Vantage Press, 2000). The author also obtained statistical information from Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Staten Island and Brooklyn were incorporated into New York City in 1898, 13 years after the opening of St. George Grounds.

2 “Metropolitans Beaten at Home,” New York Tribune, April 23, 1886: 8.

3 Yankee Stadium was built on a 10-acre parcel purchased from the estate of William Waldorf Astor, once the richest man in the world. At the time it was purchased, the parcel was a garbage-strewn, temporary lumberyard for the Astor estate. “1923: The Foul Bulls That Went on a Rampage at Yankee Stadium>>lumberyard,” http://hatchingcatnyc.com/2014/09/09/foul-bulls-ruckus-yankee-stadium/lumberyard/, accessed February 17, 2022.

4 Located on the shoreline of Upper New York Bay, Camp Washington was less than a half-mile north of the Staten Island Quarantine, a federal facility established in 1801 to treat victims of yellow fever. The quarantine’s buildings were burned to the ground during an 1858 riot by local residents who feared that yellow fever had been spread from Quarantine occupants to the local community. “The Quarantine War,” New York Herald, September 17, 1858: 2; Andy McCarthy, “Forgotten History: The 1858 Quarantine Fires in Staten Island,” March 27, 2020, https://www.nypl.org/blog/2020/03/27/1858-quarantine-fires-staten-island, accessed February 17, 2022.

5 “Quickstep Club of Tomkinsville [sic],” Protoball website, https://protoball.org/Quickstep_Club_of_Tomkinsville, accessed February 28, 2022. In Green Cathedrals, author Philip J. Lowry claims that in 1853, the Knickerbockers faced the Washington Club at St. George Grounds. Happening three decades before St. George Grounds was built, such a contest was most likely played instead at the Elysian Fields, home field of the St. George Cricket Club. Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals, 5th edition (Phoenix: SABR, 2019), p. 280.

6 Their uniforms styled after those of the elite Zouave battalion of the French Army, the 5th played prominent roles in the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Battle of Fredericksville, and the Battle of Chancellorsville. Charles Gilbert Hine and William Thompson Davis, Legends, Stories and Folklore of Old Staten Island: The North Shore (New York: Staten Island Historical Society, 1925), p. 7; “5th Infantry Regiment,” https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/unit-history/infantry/5th-infantry-regiment, accessed February 18, 2022.

7 Law’s undeveloped land holdings along the shoreline are shown in an 1874 Richmond County atlas, totaling 15-20 acres (with one structure shown), bordered by Hyatt and Jay Streets. Roger P. Roess and Gene Sansome, The Wheels That Drove New York: A History of the New York City Transit System (New York: Springer, 2013), p. 228; Atlas of Staten Island, Richmond County, New York (New York: J.B. Beers & Co, 1874), p. 6, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e2-0b93-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99/book?parent=90fbf4a0-c5f7-012f-2c6e-58d385a7bc34#page/7/mode/2up, accessed February 11, 2022.

8 “Staten Island,” New York Times, April 24, 1873: 8.

9 “How ‘Love’ Term Prevailed,” Sacramento Bee, December 20, 1919: 39; “Mary Outerbridge,” International Tennis Hall of Fame, https://www.tennisfame.com/hall-of-famers/inductees/mary-outerbridge, accessed February 18, 2022; Amisha Padnani, “Mary Ewing Outerbridge,” Staten Island Cricket Club, https://www.statenislandcc.org/outerbridge, accessed February 18, 2022.

10 The first American tournament consisted of matches between members of the by-then renamed Staten Island Cricket and Baseball Club. Lawn tennis exploded in popularity soon after, with area newspapers reporting on Camp Washington tournaments up through 1885. “Lawn Tennis,” New York Herald, August 23, 1877: 5; “Lawn Tennis on Staten Island,” New York Sun, September 3, 1880: 1; “Lawn Tennis at Staten Island,” Brooklyn Union, October 11, 1885: 8.

11 Wiman later credited Buffalo Bill Cody’s manager with giving him the idea for a resort on Staten Island’s north shore, after the manager inquired whether Wiman realized “what a grand site Staten Island would be for a great ‘recreation ground,’ being easily accessible to three millions of people.” “New Pleasure Grounds,” New York Times, June 20, 1886: 2.

12 “Rapid Transit in Staten Island,” New York Tribune, April 20, 1880: 8.

13 “To Staten Island,” New York Times, April 4, 1883: 5; “Ferry Franchises Sold,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 17, 1884: 4.

14 The sale price was initially reported by the New York Times as $100,000, then later revised to $175,000. Wiman was purportedly executing a long-standing option to buy the Camp, which he had negotiated with Law before his Law’s death. After two previous options had expired, Law was said to have granted Wiman’s request for a third option after the latter offered to “canonize” Law by naming his planned ferry terminal St. George. “Staten Island,” New York Times, January 27, 1884: 5; “Staten Island Improvements,” New York Times, October 31, 1884: 8; Legends, Stories and Folklore, p. 6.

15 Staten Island Improvements,” New York Times, October 31, 1884: 8.

16 While Wiman looked for a drawing card, the Staten Island Cricket Club’s Camp Washington lease was extended. Their activities at Camp Washington included occasional baseball games. In 1883, the Brooklyn Eagle called the Staten Island Cricket Club nine the most prominent amateur club in metropolitan New York. Their roster was filled with talented Ivy League players, including a battery of Harvard College standout Jim Tyng and former Yale captain, Al Hubbard. (It was Tyng whose refusal to catch the swift pitches of a fellow Crimson pitcher without face protection prompted Harvard captain Fred Thayer to fashion the very first catcher’s mask in the spring of 1877.) Professional nines hosted at Camp Washington in 1883 included the pennant-winning Brooklyn club of the Interstate Association and the NL’s second-place Providence Grays. The cricket club continued to host amateur games at Camp Washington through at least September 1885. “Sports and Pastimes,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 15, 1883: 3; “Amateurs vs. Professionals,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 31, 1883: 3; “An Amateur’s Invention,” Boston Globe, March 27, 1886: 5; “The Brooklyn Live Oaks Defeated by Staten Island,” Brooklyn Union, September 1, 1885: 3.

17 “Base Ball by Electric Lights,” Sun (New York),” December 6, 1885: 2.

18 At that time, Staten Island had no direct access to neighboring Manhattan and Brooklyn and was reachable only by boat. Earlier that year, Day, owner of both the Metropolitans and the National League’s New York Giants, had shifted the Mets manager Jim Mutrie to his NL club, and absconded with Mets ace Tim Keefe and slick fielding third baseman Dude Esterbrook through a slight of hand that demonstrated his clear preference for his NL club. “Mr. Wiman’s Baseball Club,” New York Times, December 5, 1885: 8; “A $25,000 Ball Club Dropped,” Buffalo Evening News, December 9, 1885: 1.

19 Perversely, in making their case for why allowing a Staten Island franchise would result in a “direct pecuniary loss” to the Association, the AA argued that Day’s release of Keefe and Esterbrook earlier that year (done in order to move them to the Giants), and his subsequent inaction in providing the Mets with replacements of comparable talent (not done in order to save money), had “spoiled [the Mets’] reputation,” thereby diminishing attendance at their games. “A Victory for the Mets,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, December 20, 1885: 1; “The Baseball Muddle,” Marion County Herald (Palmyra, Missouri), January 1, 1886: 2.

20 The term “gallery” was used by the New York Times to describe each level of the grandstand. The grandstand was erected by a construction firm owned by Daniel Campbell, who would go on to become the Commissioner of the Department of Buildings for both Richmond and Queens Counties when they were incorporated into New York City in January 1898. “Hard by the Ferry,” New York Times, March 14, 1886: 14; Illustrated Sketch Book of Staten Island, New York (New York: Standard Printing and Publishing Co., 1886), p. 45; “Gotham Gossip,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana), June 28, 1886: 8; “What Builders are Doing,” Carpentry and Building, February, 1898: 38.

21 Woodruff designed several other buildings for the Staten Island Amusement Company. Many years later, he won the Phebe Hobson Fowler Architectural Award for his design of the Angel’s Gate Light, a lighthouse that is still standing in the harbor of Los Angeles, California as of 2022. Illustrated Sketch Book; “Obituary,” Engineering World, December 1, 1919: 67; https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t8pc3sm6m&view=2up&seq=8&skin=2021, accessed February 26, 2022; Los Angeles Harbor (Angel’s Gate) Lighthouse, Lighthouse Friends website, https://lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=99, accessed February 26, 2022.

22 “Hard By the Ferry.”

23 “Hard By the Ferry.”

24 Seating capacity of the Grounds also varied as reported by New York newspapers, from slightly over 4000 to 8000. “Hard By the Ferry”; “Curiosities of Base Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 4, 1886: 7; “Illuminated Fountains,” New York Times, July 1, 1886: 5.

25 George F. “Major” Williams, general manager of the Staten Island Amusement Company, anticipated the Grounds would provide cuisine and bars equal to the finest in New York, enabling visitors to enjoy a “comfortable table d’hôte or à la carte dinner at a reasonable price” on hot summer evenings. “Hard by the Ferry.”

26 “New St. George Grounds.”

27 “Staten Island,” New York Tribune, March 7, 1886: 8.

28 A description of progress on the grandstand’s construction places the ferry slip 300 feet from the grandstand. A map generated by a community organization in 1888 which depicts the grandstand located immediately south of Wall Street suggests that the ferry must have been further from the grandstand. “Hard By the Ferry.”; Robert A. Welke, Map of New Brighton, SI, New Brighton Village Improvement Association, 1888, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bf9e1342-6c01-1935-e040-e00a180603be

29 Contemporary newspapers referred to the Metropolitans opponent as the Athletics of Philadelphia, rather than the name typically used in the 20th century, the Philadelphia Athletics.

30 “Metropolitan and Athletic,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 23, 1886: 3.

31 “Metropolitans Beaten at Home.”

32 Identified as the Mets in most New York newspaper story titles and game descriptions, they were usually listed as the Metropolitans in box scores, so as not to be confused with the NL Giants. The Mets were also referred to as the Indians, especially by the New York Sun, following a popular promotion in 1885 in which Mets players were referred to by Indian names. The “Chief” nickname followed part-Native American outfielder James Roseman through the remainder of his career. Larry Lupo, When the Mets Played Baseball on Staten Island (New York: Vantage Press, 2000), p. 13.

33 “Spring Recreation,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 19, 1886: 3; Threads of Our Game, 19th-century baseball uniform database, https://www.threadsofourgame.com/1886-metropolitan-new-york/#, accessed February 14, 1886.

34 “New St. George Grounds.”

35 “Liberty and Her Pedestal,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 23, 1886: 4.

36 “New St. George Grounds.”

37 “Base-Ball on Staten Island,” Harper’s Weekly, May 15: 1886: 311-312.

38 “Metropolitans Beaten at Home.”

39 “Base-Ball Notes from New York,” Chicago Tribune, June 13, 1886: 10.

40 “The Brooklyns Win Again,” New York Tribune, April 24, 1886: 8.

41 It was the last of five home runs in Farrell’s brief career. “The Baltimores Defeat the Metropolitan by 10 to 3,” Baltimore Sun, May 5, 1886: 6.

42 Orr is tied with fellow Mets James Roseman, Paul Radford and Charley Jones for the most career home runs hit at the Grounds, with three apiece. Based on the author’s compilation from box scores published in the New York Times, New York Sun, and Sporting Life. “The ‘Mets’ Win a Game,” New York Times, May 7, 1886: 3.

43 “Beaten by a Single Run,” New York Times, May 23, 1886: 2.

44 “Base-Ball on Staten Island.”

45 A week before the sketch was published, 150 yards of that fencing had blown down during a storm. “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, May 19, 1886: 5.

46 Lowry, 280.

47 Michael Gershman, Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1993), p. 39; “A Second Look at the Illustrations in ‘Our National Game’,” October 17, 2018, Baseball Researcher website, http://baseballresearcher.blogspot.com/2018/10/a-second-look-at-illustrations-in-our.html, accessed March 6, 2022.

48 Ferguson, who had 14 years of experience managing in the NA, NL, and AA, resigned from his position as the highest-paid AA umpire in order to take on managing the Metropolitans. The normally right-handed batting captain of the National Association’s Brooklyn Athletics made history in 1870 when he chose to bat left-handed in a tight game against the fabled Cincinnati Red Stockings in order to keep the ball away from their great shortstop, George Wright.

49 The shutout was the first by a Mets pitcher at the Grounds. The New York Sun called the game “the best played game so far on the new Staten Island grounds. “In the Baseball Field,” New York Sun, June 13, 1886: 7.

50 The cost of the fountains, equivalent to $1.2 million in 2022 dollars, included a $25,000 licensing fee to Sir Francis Bolton. “Illuminated Fountains”; “New Pleasure Grounds.”

51 The New York Times also reported plans for St. George Grounds to host evening baseball and lacrosse using a phosphorescent ball. In another story describing the illuminated fountains, an unnamed Times-Picayune reporter bumped up the estimated grandstand capacity for planned evening concerts to 8,000, which henceforth became the number cited by most other newspapers as well. “New Pleasure Grounds”; “Gotham Gossip.”

52 Gershman, Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark; The concerts featured the fountains, the name “St. George” written in “great letters of fire,” and the Seventh Regiment Band and Drum Corps performing “airs from popular operas.” That same band, under the direction of John Phillip Sousa, performed the Star-Spangled Banner at the 1923 opening of Yankee Stadium. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper published a detailed description of the fountains, along with a nearly full page black and white sketch. “Illuminated Fountains”; “Fairyland on Staten Island,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 17, 1886: 348; Frederick C. Bush, “Babe Ruth Homers in Yankee Stadium’s Grand Opening, Hinting at Franchises Dynastic Future,” SABR website, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/april-18-1923-yankee-stadium-grand-opening-hints-at-franchises-dynastic-future/.

53 Wiman, a lacrosse player in his youth and president of both the New York and the National Lacrosse Associations, allowed the New York Lacrosse Club to continue hosting matches at the former Camp Washington after he had purchased it. In June 1886, the Grounds hosted lacrosse teams from Baltimore, Boston, Connecticut, and New York, vying for the Gelrichs Cup. Illustrated Sketch Book of Staten Island, New York, p. 42; “City and Suburban News,” New York Times, June 3, 1882: 8; “Sporting Notes,” New York Times, June 5, 1886: 8.

54 Free to all during its Sunday opening, the casino served no alcohol, invited children to attend, and offered “abundant supplies” of milk, ice cream, cake, and lemonade. The Japanese village, complete with quaint houses and unusual artisans, included woodworkers fashioning “fantastic screens, fans and other things peculiarly Eastern “Staten Island,” New York Times, June 26, 1886: 7; “Illuminated Fountains”; “Local Jottings,” The Evening Post, July 13, 1886: 1; “News of the Morning,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Evening News, August 14, 1886: 2.

55 “Caught From a Rainbow,” New York Times, July 16, 1886: 2.

56 “Buffalo Bill’s Bonanza,” New York Times, June 29, 1886: 2; Andrew Wilson, “Found Staten Island Stories 3: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, Mariner’s Harbor, 1886 and 1888,” September 23, 2016, New York Public Library website, https://www.nypl.org/blog/2016/09/23/clone-found-staten-island-stories-3-buffalo-bills-wild-west-mariners-harbor-1886-and, accessed February 15, 2022.

57 “To Rival the St. George Grounds,” Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), August 2, 1886: 6.

58 “Base-Ball Notes from New York.”

59 “The Mets Awful Luck,” The Sporting News, May 17, 1886: 1.

60 “First Ticker-tape Parade Held (1886),” Today in Conservation website, https://todayinconservation.com/2018/10/october-28-first-ticker-tape-parade-held-1886/, accessed February 21, 2022.

61 “Solved at Last,” Sporting Life, March 30, 1887: 1.

62 “In the World of Sport,” Brooklyn Times, April 2, 1887: 6.

63 An unnamed writer for The Sporting News was one well-wisher, hoping that “the finest grounds in the world will have a team of ball tossers . . . worthy to tread its velvety sward.” “Jim Mutrie Laughs,” The Sporting News, December 11, 1886: 1.

64 “The Mets Get Their First Victory,” New York Tribune, May 4, 1887: 2.

65 Mutrie coached the Columbia University baseball team for several seasons while managing the New York Giants. “The College League,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 22, 1887: 16; http://www.liskahaas.org/stagg/biography.htm, accessed February 22, 2022; Columbia Alumni News, Volume 11, No. 1 (New York: Columbia University, 1919), p. 687; “Fact and Rumor,” January 16, 1890, The Harvard Crimson website, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1890/1/16/fact-and-rumor-there-is-an/?utm_source=thecrimson&utm_medium=web_primary&utm_campaign=recommend_sidebar, accessed March 5, 2022.

66 Playing only two of their first 30 home games torpedoed the Mets season. For the season, the Mets would play 15 more away games than home games. This disparity was due in part to the AA practice of allowing teams to reschedule games from the home park of a weaker team to that of a stronger team in order to maximize gate receipts for both teams. Robert Allan Bauer posits that this practice skewed the pennant race, depressed attendance league-wide, and accelerated the demise of the league. Robert Allan Bauer, “Outside the Lines of Gilded Age Baseball: Profits, Beer, and the Origin of the Brotherhood War,” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 2015, ScholarWorks@UARK website, https://scholarworks.uark.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2214&context=etd, accessed March 1, 2022.

67 The Fall of Babylon premiered in Cincinnati during the summer of 1886 to rave reviews. “Personal Observations,” New York Sun, March 7, 1887: 2.

68 “The Fall of Babylon,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 24, 1887: 15; “Coming Attractions at Staten Island,” New York Tribune, April 24, 1887: 9; “News of the Theatres,” New York Sun, May 29, 1887: 14; “The Fall of Babylon,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 12, 1887: 16.

69 “Paragraphs of Opera and Play,” Boston Globe, June 5, 1887: 10.

70 “Metropolitan, 6; Cincinnati, 13,” New York Sun, June 14, 1887: 3.

71 “The Queen’s Jubilee,” New York Tribune, June 21, 1887: 7; Brooklyn Eagle, June 23, 1887: 1; “Sporting Notes,” Richmond County (New York) Advance, June 25, 1887: 5.

72 “Metropolitans, 0; Brooklyn, 2,” New York Sun, June 26, 1887: 3.

73 Radford was a Methodist who refused to play Sunday games throughout his career. He hit a pair of homers on June 16, against the Cincinnati Red Stockings’ Billy Serad. “Nine Innings Not Enough,” New York Times, June 17, 1887: 2; Charlie Bevis biography of Paul Radford, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/paul-radford/.

74 “Orr’s Great Drive,” Brooklyn Citizen, June 25, 1887: 2.

75 “News of the Theatres,” New York Sun, July 10, 1887: 5; “Babylon’s Fall a Great Success,” New York Times, August 7, 1887: 9.

76 During infield practice for one game at the Grounds, the Athletics had several elephants and camels parade through the outfield on their way to the show’s zoo. “Metropolitan, 9; Athletic, 0,” New York Sun, August 13, 1887: 3; Lowry, 280; Frank Vaccaro, Ted Sullivan SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ted-sullivan/.

77 Despite the many fans that attended ballgames and theatre at the Grounds that summer, profits were likely meager. The club’s desire to rake in more gate receipts is evident in their decision to skirt New York’s blue laws and twice play on Sundays in September in nearby Weehawken, New Jersey. On September 4, a crowd estimated at between 6,000 and 13,000 was on hand to see the Mets face the St. Louis Browns. They so overwhelmed the 1,500-seat ballpark that fans sat on the grandstand roof and on the field, close to both infielders and outfielders. After one fruitless inning of play, umpire, and former Mets manager, Bob Ferguson waved the players off the field, which prompted a near riot by the crowd. The game resumed as an exhibition with a different umpire. Crowding was so severe that the scorers “held their valuables in their hand while scoring as it was a frequent occurrence to find another man’s hand in one’s pocket by mistake. The Mets successfully played an official game the following Sunday against the Louisville Colonels, in front of far fewer (1,500) spectators and many more policemen than were on hand the week before. “Not to Go Away,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 17, 1887: 5; “On the Diamond Field,” Brooklyn Standard Union, September 5, 1887: 4; “The Game at Weehawken,” New York Sun, September 5, 1887: 3; “Playing at Weehawken,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 5, 1887: 6; A Victory for Louisville,” New York Times, September 12, 1887: 2.

78 Wiman is reported as having lost $30,000 in the two seasons he owned the Metropolitans franchise. “The Metropolitans Sold,” New York Times, October 9, 1887: 3.

79 During the abortive attempt to deny Wiman a franchise in December 1885, Byrne had several Metropolitans reassigned to his Grays. He persuaded a pair of Mets to sign Brooklyn contracts but was forced to relinquish them when the AA owners group reinstated Wiman’s franchise. “The Mets Have Their Innings,” New York Sun, December 10, 1885: 3; “The Baseball Muddle,” Marion County Herald (Palmyra, Missouri), January 1, 1886: 2.

80 Wiman spent much of his time in this period promoting a free-trade agreement with his native Canada and securing investors for his “cyclone coal economizer” device for improving energy efficiency. Local amateur sporting events were likely held at the Grounds in front of an echoing grandstand, but none were significant enough to attract the attention of local newspapers. “Reciprocity,” Buffalo Times, December 29, 1887: 2; “A Revolution in Fuel,” New York Tribune, January 29, 1888: 15; “Dramatic Notes,” Buffalo Commercial, April 21, 1888: 4.

81The Nero stage was deeper, wider, and placed 200 feet closer to the grandstand, than the stage used for The Fall of Babylon. The exact dimensions of the Nero stage differed in newspaper accounts. “Actors, Managers and Plays,” New York Tribune, May 23, 1888: 4; “Rome Will Fall on Monday Night,” New York Evening World, June 23, 1888: 3; “Nero Exceeds Even the Fall of Babylon,” New York Tribune, July 8, 1888: 16; “Imre Kiralfy’s New Spectacle,” New York Evening World, May 12, 1888: 4; “Kiralfy’s New Spectacle,” New York Sun, May 17, 1888: 3.

82 Blondin’s act included riding a wheeled cart, turning a somersault, walking with his eyes covered and sitting on a chair. Nearly 30 years earlier, Blondin became the first person to cross Niagara Falls on a tightrope, which he documented with a Daguerreotype camera he had carried strapped to his back. Blondin repeated his Niagara Falls crossing several times, including once with President Millard Fillmore in attendance. “It’s the Old Blondin,” New York Sun, June 24, 1888: 6; Karen Abbott, “The Daredevil of Niagara Falls,” October 18, 2011, Smithsonian Magazine website, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-daredevil-of-niagara-falls-110492884/, accessed February 27, 2022.

83 “Nero Exceeds.”

84 “Stabbed in Reality in the Play,” New York Tribune, July 12, 1888: 1.

85 “Threatened with Real Destruction,” New York Evening World, August 28, 1888: 3.

86 “News of the Stage,” New York Evening World, August 31, 1888: 3.

87 “Walks About the City,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 23, 1888: 6.

88 “In and Out Door Sports,” New York Sun, February 9, 1889: 3.

89 Day agreed to pay Wiman $6,000 a year to rent the Grounds. “Abandoning the Polo Grounds,” New York Tribune, April 19, 1889: 3.

90 “Now the Interest Grows,” New York Tribune, March 31, 1889: 15.

91 “The Diamond Field,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 27, 1889: 1; “Giants at St. George,” New York Evening World, April 29, 1889: 1.

92 “In and Out Door Sports,” New York Sun, April 27, 1889: 6.

93 “Base Ball Galore,” New York Sun, April 30, 1889: 8.

94 Midseason, the Giants traded for O’Day, who won nine games down the stretch to lead the Giants to their second NL championship. In the Giants subsequent World Series triumph over the AA champion Brooklyn Bridegrooms, it was O’Day who won the deciding contest. Dennis Bingham, Hank O’Day biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/hank-oday/.

95 The umpire was likely Jack McQuaid, listed in Retrosheet.com as having umpired NL games beginning in 1889.

96 Balls that bounced over an outfield fence were typically declared home runs across organized baseball until well into the 20th century.

97 “Base-Ball Notes,” Indianapolis Journal, May 29, 1889: 3.

98 “Clipping: The undesirability of the St. George grounds,” Protoball website, https://protoball.org/Clipping:The_undesirability_of_the_St._George_grounds, accessed March 1, 2022.

99 “What is the Trouble,” Chicago Tribune, June 9, 1889: 13.

100 Attendance was estimated at 43,000 through their first 19 home games at the Grounds. Sporting Life opined that a Decoration Day game which drew 5,000 at the Grounds would have attracted at least 20,000 at the Polo Grounds. “The Polo Ground Question,” Sporting Life, June 5, 1889: 7; Sporting Life, June 5, 1889: 4; “Our Pitchers in Form,” New York Sun, June 12, 1889: 6.

101 “New York, 14; Philadelphia, 4,” The New York Sun, June 15, 1889: 6.

102 The Giants rained-out June 15 contest with the Philadelphia Athletics was expected to draw one of the largest crowds of the season. Before the start of their June 17 rematch, captain Buck Ewing and owner Day, with hoe [hoes?] in hand, led a work crew in making the field playable from the previous storm. A subsequent downpour forced the Giants to send home a “boatloads of enthusiasts.” “Our Bad Luck Continues,” New York Sun, June 18, 1889: 6.

103 Weeks earlier, Sporting Life had suggested that Grays owner Charles Byrne was benefiting by many New Yorkers preferring to attend games in Brooklyn, rather than “taking the long ride to Staten Island.” “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, May 15, 1889: 4; “Staten Island’s Disadvantages,” Sporting Life, May 15, 1889: 4.

104 “Our New Ball Grounds,” New York Sun, July 9, 1889: 6.

105 The Ground’s casino hosted bowling events, served as an Election Day polling place, and was a meeting place for county political conventions, community gatherings and Wiman’s many business enterprises. The baseball diamond was home to community leagues and special event games. The last ballgame noted at the Grounds was in August 1892, during a local church picnic. “Election Notice,” Richmond County Advance, September 20, 1890: 5; “Presentation,” Richmond County Advance, October 4, 1890: 1; “At the Casino Next,” Richmond County Advance, October 4, 1890: 1; Richmond County Advance, October 11, 1890: 4; “Big Time,” Richmond County Advance, August 29, 1891: 8; “Sporting,” Richmond County Advance, April 23, 1892: 5; “St. Peter’s Picnic,” Richmond County Advance, August 13, 1892: 1.

106 The New York Evening World predicted a crowd of up to 40,000 for the event, to be held following Sullivan’s Hattiesburg, Mississippi match with challenger Jake Kilrain. Sullivan won that fight after an astounding 75 rounds. Sullivan spent a few days in the New York area a few weeks after the bout, but the Staten Island testimonial was never held. “A Sullivan Testimonial Planned,” New York Evening World, July 10, 1889: 3; “John L. Sullivan Wins,” New York Sun, July 9, 1889: 1.

107 Chicago was ultimately selected over New York, St. Louis and Washington D.C. to host what became known as the World’s Columbian Exposition, which opened in May 1893. “Looking for a Site,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 1, 1889: 16; “Staten Island Property Owners,” New York Herald, September 8, 1889: 11.

108 “The Wiman’s Pluck,” Ottawa (Ontario, Canada) Journal, October 7, 1893: 1; Bill Lamb, Erastus Wiman biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/erastus-wiman/.

109 Insurance Maps of the Borough of Richmond, City of New York (New York: Sanborn Map Co., 1898), plate 47.

110 Based on examination of aerial photographs. Sectional Aerial Map of the City of New York, 1951, No. 21, https://nycma.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/view/search/who/Aero+Service+Corp.?q=staten+aerial+1951&pgs=50&res=1; Staten Island ‘under construction:’ The St. George ferry terminal/Then and now, Staten Island Live website, February 11, 2022, https://www.silive.com/entertainment/2022/02/staten-island-under-construction-the-st-george-ferry-terminal-then-and-now.html

111 “Observation Wheel Raises,” New York Daily News, May 16, 2013: 36; “S.I. harboring optimism for shops at ferry,” New York Daily News, April 17, 2015: 16. In 2000, Richmond County Bank Ballpark was built on the north side of Wall Street, across from where St. George Grounds once stood. Named for a local bank incorporated two days after the Statue of Liberty was dedicated, the stadium was home to the Class-A Staten Island Yankees from June 2001 to the end of the 2019 season.

112 See for example, Lowry, 280; “St. George Cricket Grounds,” Ballparks Database website, https://www.seamheads.com/ballparks/ballpark.php?parkID=SAI01, accessed March 3, 2022.

113 Mets pitcher Jack Lynch called Metropolitan Park a place where you could “go down for a grounder and come up with six months of malaria.” “Notes,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 22, 1884: 10; Bill Lamb, Metropolitan Park (New York) biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/metropolitan-park-new-york/.

114 Mauer/Brooks returned to the amateur ranks soon after this, his only professional game appearance. Other players to debut at St. George Grounds included Spider Clark (1889), Al Krumm (1889), Bill Collins (1887), Bill Fagan (1887), Charlie Hall (1887), Fred O’Neill (1887), Peter Connell (1886), John Meister (1886), John “Cannonball” Shaffer (1886) and Elmer Foster (1886), who as this author uncovered elsewhere, debuted in the inaugural game played at the Grounds. “The Mets Beaten Badly,” New York Times, July 25, 1886: 5; Bill Carle, “Fred Mauer Found,” SABR Biographical Research Committee, January/February 2015 Report, p. 1: Bill Carle, “Henry Frank Brooks,” SABR Biographical Research Committee, January/February 2014 Report, p. 2; Larry DeFillipo, “April 22, 1886: Visiting Athletics walk-off Metropolitans in inaugural game at St. George Grounds,” SABR Games Project story.

115 Spink’s story was an identical copy of a yarn first published by the Baltimore Sun in May of 1903. Ryan did in fact hit a home run at St. George Grounds, off Tim Keefe in the sixth inning of a May 25, 1889, victory over the Giants. Detailed newspaper accounts of the game make no mention of a passing ship, simply noting that once the ball was hit over the fence, “it stayed there.” Al Spink, The National Game (St. Louis: National Game Publishing Co., 1910), p.367; “Hit Across the Ocean,” Baltimore Sun, May 11, 1903: 9; “Chicago Wins by One Run,” New York Times, May 26, 1889: 3; “A Big Day in Baseball,” New York Sun, May 26, 1889: 13.