SkyDome (Toronto)

This article was written by Allen Tait

The term “nova” is a good metaphor for describing the story of SkyDome. The stadium burst on the scene in 1989 and shone brightly as a state-of-the-art multi-use stadium. It was the first stadium with a fully retractable roof, the first that helped attract 4 million fans in a season for baseball and the first stadium to host a World Series game that was not played on US soil.

The term “nova” is a good metaphor for describing the story of SkyDome. The stadium burst on the scene in 1989 and shone brightly as a state-of-the-art multi-use stadium. It was the first stadium with a fully retractable roof, the first that helped attract 4 million fans in a season for baseball and the first stadium to host a World Series game that was not played on US soil.

However, by 1993 the stadium began to lose its luster due to a combination of construction debt for original construction “add-ons” plus a “multi-use” seating design that did not always provide the best sight lines for the primary stadium function of baseball. Despite these challenges, SkyDome remained in use and in late 2021, plans for additional stadium upgrades were announced.

The Vision

The vision of a domed ballpark for Toronto predates the city obtaining a franchise. Paul Godfrey, first elected as an alderman in 1968, attended the 1969 baseball winter meetings and asked Commissioner Bowie Kuhn for a franchise. The response: “Let me tell you the way we do it in major-league baseball. First, you build a stadium. And then we consider if we want to give you a baseball team.”1

In 1973 Godfrey had been reelected to the Metropolitan Toronto Council and was selected as chair by his fellow peers. Godfrey promised to deliver a baseball franchise, domed stadium, and conference center.2 Obtaining financing to construct a new domed stadium did not seem feasible so the focus was on renovating the existing Exhibition Stadium, which was then being used by the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League and hosted rock concerts.

Exhibition Stadium was intended to be a temporary facility until a domed stadium could be built. The stadium had adequate capacity: 38,522 (1977); 43,737 (1978).3 Seating, however, could be uncomfortable. Only the outfield bleachers had a roof. Ten sections along the first-base/right-field line were aluminum benches.

Weather was always a concern for early- and late-season games at Exhibition Stadium. Concerns were greater as the prospect of the Jays playing in the postseason became legitimate with the team showing true progress starting in 1982. While summers are pleasant in Toronto, average highs between 72 and 82 degrees Fahrenheit from June through September, the average lows and highs for April (38-53), May (51-68), and October (46-59) made for some unpleasant conditions at times. The discomfort level was magnified by the lack of cover for fans excluding the bleachers and, particularly in the spring, the warmer southerly winds were cooled by Lake Ontario, which was immediately south of the stadium. The phrase “cooler by the lake” is used with some frequency in spring weather forecasts for Toronto.

The Construction

Official progress for construction of a domed stadium began in 1983 when Ontario Premier William Davis proposed the construction of a $150 million (CDN) domed stadium supported by all three levels of government (federal, provincial, municipal).4 As for location, after an eight-month study a location was originally recommended at Downsview Park. The park is approximately 11 miles from downtown Toronto and was adjacent to the federally owned Downsview Airport, an air-force base, not a civilian airport. The location was accessible by highway and public transit. However, the federal government was not interested in having a stadium in the vicinity of its federal asset.5 The Canadian National Railway offered an undeveloped railyard land by the CN Tower and the site was selected in January 1985. This location was also attractive by being downtown and within easy walking distance of Union Station, a major transportation hub for the Toronto subway system as well as the primary commuter and intercity railway terminal for Toronto.

The federal government was also not interested in providing financing, thus necessitating a public/private partnership with a sharing of profit and risk. An August 1983 feasibility study stated, “Our analysis indicates that private financing is not a viable method for the domed stadium. The main reason is projected net operating revenues are insufficient to generate positive cash flows (after debt service).”6 A 25-member corporate consortium was organized with each corporate partner to contribute $5 million each in exchange for exclusive promotion or concession rights at the stadium.7

The next task was selection of an architect. The selection of the contract of architect Rod Robbie (six employees, zero experience in building skyscrapers, shopping malls, or convention centers) in conjunction with Canadian structural engineer Michael Allen to design the retractable roof was met with skepticism.8

The construction contract was awarded to EllisDon for an original lump sum price of $184.2 million. During construction, the scope was expanded to include a hotel, health club, restaurants, “Skybox” luxury suites, and a Jumbotron scoreboard, causing the budget to increase to $527 million.9

From a technology perspective, the skeptics were wrong. The roof did work on day one and continues to work to this day. The roof is 339,343 square feet in area, weighs 11,000 tonnes10 with a maximum height of 282 feet. The roof is comprised of four panels. Panel four is stationary; panels two and three slide along horizontal rails and panel one slides in a circular motion to tuck under panels two and three.11 The roof can open/close in about 20 minutes. Subsequent to SkyDome, other stadiums with retractable roofs have been built in Phoenix (1998), Seattle (1999), Milwaukee (2001), Houston (2002), Miami (2012), and Arlington, Texas (2020).

Budget management for construction of SkyDome was not a success story. The corporate consortium financing construction expanded the contract scope as noted above to increase the potential revenue stream. Hence the SkyDome design evolved from a baseball stadium to a multipurpose facility including baseball. It was billed as “The World’s Greatest Entertainment Center”12 The final construction cost for the SkyDome, including interest charges, is estimated at $650 million.13

SkyDome comprises five decks; however, in terms of seating capacity, SkyDome was 19th in seating capacity in comparison to the 26 stadiums in use at the time it opened.14 Regular tickets for fans were available in tiers 1 and 5 and part of tier 2. Ticket prices in 1990 were $15 for all tier-1 seats between the foul poles and all outfield tier-2 seats. Outfield tier-1 seats were $12. Tier-5 tickets were $12, $9, or $4 depending on location.15 Tier-2 also included 5,800 SkyClub seats roughly foul line to foul line, costing $2,000 to $4,000 for the season. Tiers 3 and 4 were the location of 161 SkyBox luxury suites costing $150,000 to $225,000 per season.16

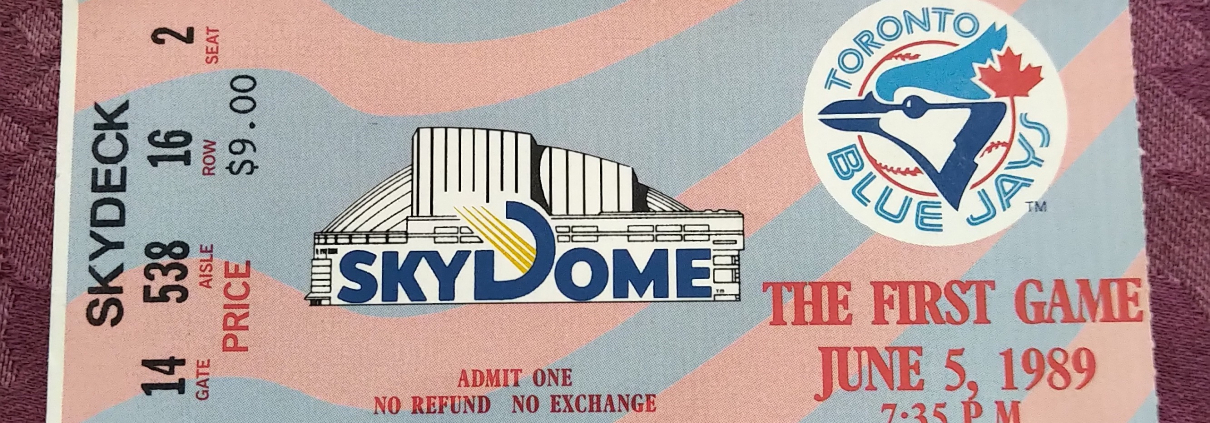

SkyDome was scheduled to open for the start of the 1989 season, but labor strikes delayed the opening.17 It opened for baseball on Monday, June 5, 1989.18 A detailed write-up of the first game, written by Adrian Fung, can be found online at the SABR Games Project.19 However, the first event, an opening gala on Saturday, June 3, left some patrons unhappy with their first SkyDome experience.20 The 90-minute program for the opening ceremonies gala, hosted by Canadian celebrities Alan Thicke (Growing Pains) and Andrea Martin (SCTV) were themed around the retractable roof. Tickets were priced from $57 to $252, or $5,000 for a 12-seat SkyBox.21 The roof was closed at the start of the gala and there were thunderstorms in the area. The gala finale was to include an opening of the dome and a decision was made to do so despite the weather, soaking the 45,000 spectators and entertainers. Upset attendees were offered free dry cleaning and 6,000 took up the offer.22

Game ticket to the Blue Jays home opener at SkyDome on June 5, 1989. (Courtesy of Gwyneth Gibson)

The Glory Years 1989-1993

Baseball fans were enthusiastic about SkyDome. Despite playing the first 26 games at Exhibition Stadium that season, the Blue Jays still led the major leagues in attendance by selling out 50 of 54 home dates and drawing 3,375,883 fans.23 Support carried over as the Blue Jays set a new major-league attendance record on September 17, 1990, and in 1991 became the first club to draw over 4,000,000 fans.

The Blue Jays again drew over 4,000,000 fans in the World Series championship years of 1992 and 1993. The team led the American League in attendance for six consecutive seasons (1989-1994). Toronto led major-league baseball in attendance from 1989 to 1992 before being passed by the expansion Colorado Rockies in 1993 and 1994 who played at Mile High Stadium with capacity in the range of 76,000.24

SkyDome was very busy during this era. In addition to hosting Blue Jays fans, other events held included being home to the Canadian Football League Toronto Argonauts, hosting the 1989 and 1992 Canadian Football League Championship Game (Grey Cup), an NBA exhibition game, lacrosse, tennis, cricket, ice-skating shows, Wrestlemania VI, Supercross, concerts, trade shows, the opera Aida, and a stage production of Les Misérables.25

Financial Pressures

Despite strong attendance for the Blue Jays and the many other events being held at the SkyDome, the stadium was losing money. Cash flow by 1993 was insufficient to service the outstanding stadium debt and interest payments were not being made. Hence the outstanding debt on the stadium had climbed to $400 million. A recalculation of cash-flow budgets indicated that the SkyDome had to be open for events 600 days per year to cover costs and generate a small profit.26

Although the original agreement was for a sharing of profit and risk between the corporate consortium and the provincial government, the government ended up protecting the consortium members from the overrun losses and this led to a $300 million write-off being incurred by the provincial government.27

In 1993 the provincial government sold the SkyDome to a private company for $150 million. Despite the sale price at around the original stadium budget, finances did not improve. In 1998 the owners filed for bankruptcy indicating they were losing $3 million per year and owed millions in back property taxes.28 In 1999, SkyDome was sold under supervision of a bankruptcy court for $80 million to Sportsco International Limited Partnership. In 2004 the current Blue Jays ownership purchased the $650 million stadium for $25 million and renamed the facility the Rogers Centre.29

Rogers Centre Era

SkyDome continues to operate today, although additional investment has been needed. In 2013 then Blue Jays president Paul Beeston noted that it required $250 million of renovations and upgrades to remain comparable to contemporary baseball standards.30

Significant upgrades included replacement of the sliding pits with a full dirt infield in 2016;31 a rebuild of the retractable roof operating system that extended into the 2016 season;32 and, new AstroTurf installed for the 2021 season.33

A few other notable events at SkyDome:

- It served as home to the Canadian Football League Toronto Argonauts for 27 seasons (1989-2015).

- It served as the original home to the National Basketball Association Toronto Raptors from November 1995-February 1999.

- Occasional rain delays occurred when the roof did not close in time at the onset of sudden rain.

- On three occasions, fans either assumed or forgot their hotel rooms facing the playing field were not one-way glass and provided “X-rated” entertainment to fans in the stands.34

- Two 30-pound roof tiles fell during a game on June 22, 1995, injuring seven fans.35

- A game on April 12, 2001, was postponed when two of the three roof panels collided, sending roof siding and insulation debris into left field during Kansas City Royals batting practice; no one was injured.36

In 2020 the future of SkyDome was in doubt. The Blue Jays had proposed that it be torn down and replaced with a new stadium at the existing site. After further study, the Blue Jays announced in late 2021 that SkyDome would be renovated instead.37 The reconstruction plan would have required five years to complete with the Blue Jays having to find a temporary home park during the construction period. The renovation plan will focus on renovating the lower bowl of the existing stadium.

Upon reflection, SkyDome may not have received a balanced review of its accomplishments. It is very easy to criticize the cost overrun and falling into bankruptcy 10 years after it was built. Being a circular multipurpose stadium, sight lines for some seats were not considered ideal for watching baseball. However, as current (2022) Blue Jays President Mark Shapiro noted in an interview reflecting on the 30th anniversary of SkyDome, the stadium was a state-of-the-art multi-use facility when it opened in 1989. It had the largest Jumbotron of its era. However, it opened at the end of the multi-use stadium era.38

The legacy of SkyDome includes the accomplishments that it hosted the first World Series game not on US soil, hosted back-to-back World Series titles for the Blue Jays, and was the first stadium to draw 4,000,000 fans in a single season. The financial challenges should not distract from the proud legacy of the stadium.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the Baseball-Reference.com website.

Notes

1 Stephen Brunt, Diamond Dreams: 20 Years of Blue Jays Baseball (Toronto: Viking, 1996), 17.

2 Brunt, 17.

3 Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals 5th Edition (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2019), 289.

4 Brunt, 150. All dollar figures cited are in Canadian dollars.

5 Brunt, 150.

6 Brunt, 150.

7 Brunt, 151.

8 John Mays, “Designed SkyDome as ‘a pleasure palace for the people,’” Globe and Mail (Toronto), January 6, 2012.

9 Lindsay Cole, “Raising the Roof: Toronto’s Rogers Centre Remains a Marvel,” EllisDon.com, July 4, 2017. https://www.ellisdon.com/news/raising-the-roof-torontos-rogers-centre-remains-a-marvel/, accessed January 9, 2022.

10 A tonne, or metric ton, is 2,205 pounds.

11 Cole.

12 Ira Rosen, Blue Skies Green Fields (New York: Clarkson Potter, 2001), 170.

13 Mays,

14 “Ballpark Ballistics,” Blue Jays Scorebook 14 (1990), 34.

15 Blue Jays Scorebook, 137.

16 “Countdown to SkyDome,” Blue Jays Scorebook 12 (1988), 298.

17 Blue Jays Scorebook, Collector’s Edition (1989), 136.

18 Lowry, 290.

19 Adrian Fung, “June 5, 1989: Blue Jays Play First Game in SkyDome,” SABR Games Project. sabr.org. https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/june-5-1989-blue-jays-play-first-game-in-skydome/. Accessed January 9, 2022.

20 https://www.theweathernetwork.com/ca/news/article/this-day-in-weather-history-june-3-1989-skydome-gala, last accessed December 27, 2021.

21 Blue Jays Scorebook, Collector’s Edition (1989), 136.

22 Blue Jays Scorebook 14 (1990), 106.

23 Blue Jays Scorebook 14 (1990), 38.

24 Lowry, 112.

25 Blue Jays Scorebook 14 (1990), 110-120.

26 CBC Archives, February 9, 2011.

27 Brunt, 151.

28 CBC Archives, November 26, 1998.

29 Marcus Gee, “SkyDome’s Legacy: Not with My Money, Never Again,” Globe and Mail, June 3, 2009.

30 Eric Enders, Ballparks Then and Now (San Diego: Thunder Bay Press, 2015), 154.

31 Brendan Kennedy, “Blue Jays Debut Rogers Centre All-Dirt Infield on Friday,” Toronto Star, April 7, 2016.

32 Cole.

33 Shi Davidi, “Blue Jays Getting New Astroturf Field Amid Hopes for Full Season in Toronto,” SportsNet.ca, December 11, 2020. https://www.sportsnet.ca/mlb/blue-jays-getting-new-astroturf-field-amid-hopes-full-season, last accessed December 27, 2021.

34 Lowry, 290.

35 Lowry, 291.

36 Lowry, 291.

37 Mark Zwolinski, “Renovation Planned for Rogers Centre,” Toronto Star, December 24, 2021: S5.

38 Ian Hunter, “Mark Shapiro Says Something Big Is Brewing with Rogers Centre Renovations,” BlueJaysNation.com, July 13, 2019. https://bluejaysnation.com/2019/07/13/mark-shapiro-something-big-brewing-rogers-centre-renovations/ accessed January 16, 2022.