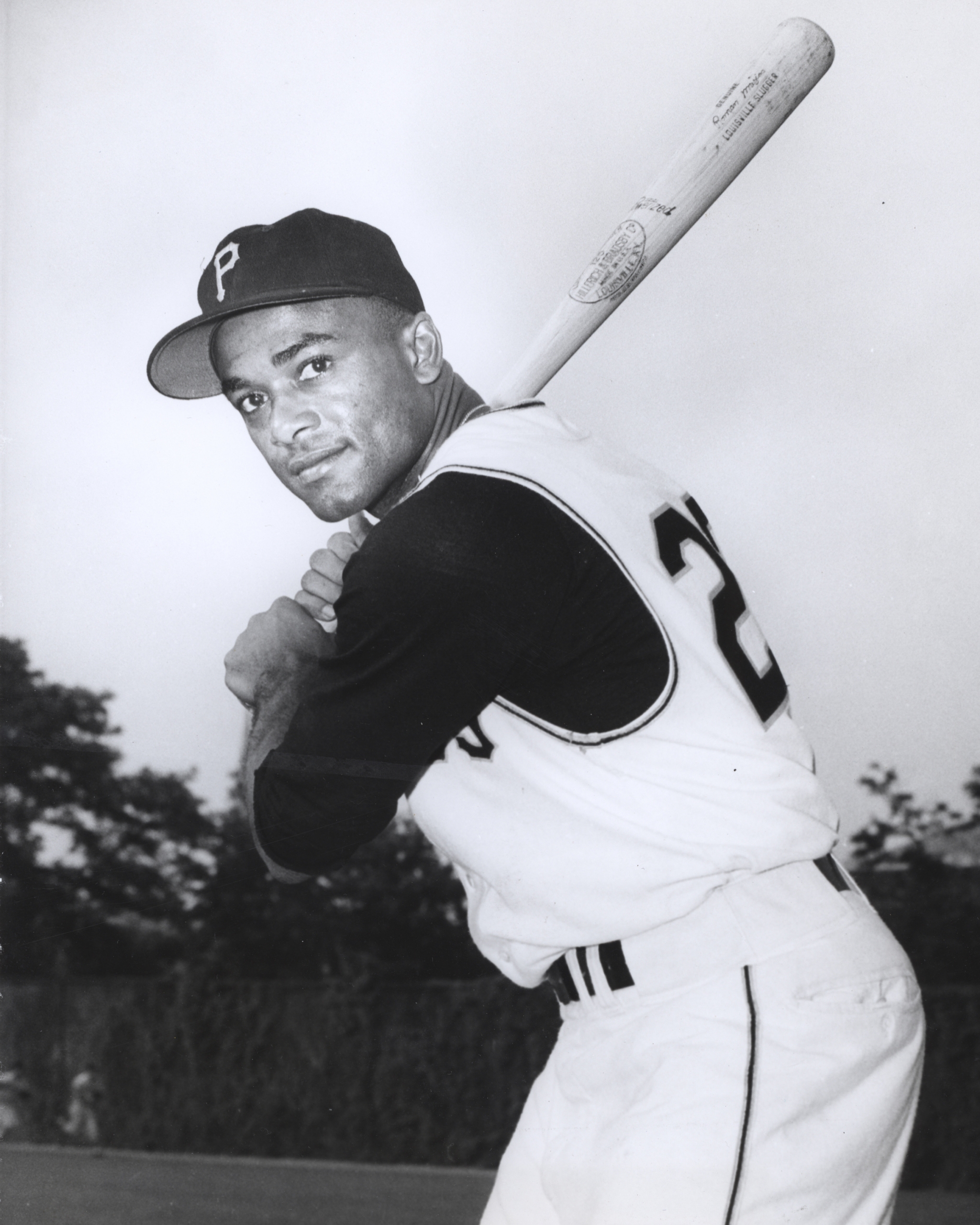

Román Mejías

Outfielder Román Mejías played in 627 big-league games from 1955 to 1964. Alas, just three of those came with the 1960 Pirates, his one US team that won a pennant. He was not on the roster when Pittsburgh won the World Series that year. Mejías was “an affable, good-natured player … whose demeanor, humility and enthusiasm reminded some people of Ernie Banks.”[1] He stood an even 6 feet tall, weighed 175 pounds, and was right-handed. He had the tools: He could hit for power and average, and he ran, threw, and fielded well. His primary position was right field, though – so that meant he was stuck behind his good friend Roberto Clemente during his time in Pittsburgh. Though Mejías could play anywhere in the outfield, the Pirates also had fine-fielding Bill Virdon in center and solid pro Bob Skinner in left. And when Pittsburgh obtained Gino Cimoli in December 1959, Mejías lost his backup position.

Mejías had played only two full years in the majors when he finally got a chance to be a regular in 1962. Then thought to be aged 29, but in reality 36, he had a breakout year with an expansion club, the Houston Colt .45s – he slugged 24 of his 54 major-league home runs during his season in the sun. He did not sustain that success, though, after an ill-considered trade to the Boston Red Sox that winter. The Houston franchise long failed to capitalize on the strongly Hispanic demographics of the Southwest by developing and marketing Latino ballplayers. The Afro-Cuban Mejías was the first example of this lack of sensitivity and appreciation.

Román Mejías Gómez was born to Manuel Mejías and Felipa Gómez on August 9, 1925. Accounts during his playing days (including his baseball cards) typically gave his year of birth as 1932, but Mejías himself later declared that it was 1930.[2] Upon his death, however, the year was shown to be 1925.[3]

Mejías also clarified his place of birth. US references have shown the city of Abreus, but it was actually Central Manuelita.[4] This sugar mill complex was in the vicinity of Abreus in the former province of Las Villas. The closest major city is Cienfuegos.[5]

Young Román completed three years of high school in Cuba, and played baseball at that level, but from a young age he worked alongside his father in a shoe factory.[6] On June 13, 1948, at the age of 22, he married Nicolasa Montero. (This date too is two years earlier than American sources showed during his career.[7]) The couple had two children, Leandra Rafaela and José.

Mejías began to climb the baseball ladder – and gain broader attention – by playing in the Pedro Betancourt Amateur Baseball League.[8] This league was based in Matanzas province in western Cuba, far from his home. It was composed of young men from around the country who sought to advance their game.

In 1953 Mejías was working as an assistant engineer on a train in Central Manuelita, loading sugarcane.[9] He joined pro baseball because the Pirates had been invited to spring training in Havana that year. Branch Rickey (then their general manager) decided to hold a tryout camp to search for prospects from the Cuban countryside. A Cuban lawyer named Julio “Monchy” de Arcos – who was also part-owner and general manager of the Almendares Alacranes, a team in Cuba’s professional league – paid for Mejías’ trip to Havana to attend the camp.

Hall of Famer George Sisler, who was then a scout for the Pirates, noticed the outfielder and signed him after a 100-mile ride with de Arcos to Mejías’s home. “If you’ve never traveled by car into the interior of Cuba, you can imagine what kind of ride we had,” said Sisler. The whole mill town (population: 300) turned out en masse to witness the signing.[10] The modest bonus was later reported to be $500.[11] SABR’s Scouts Committee gives the credit, as was often the case with international signings, to several men: Corito Varona, regional superscout Howie Haak, and Sisler. In 1985, Haak told Peter Gammons of the Boston Globe that Rickey agreed to knock eight years off Mejías’s age (though later evidence suggests it was seven).[12]

Mejías had much early success in the Pirates’ minor-league chain, beginning with Batavia in the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York League (Class D). In 117 games in 1953, he batted .322, which was second on the club, but he was team leader in slugging (.475), doubles (30), and triples (10). His 42 stolen bases led the league. He did not play in Cuba’s professional league that winter, though; it’s likely that he was not yet deemed ready for the high-level circuit.

Promoted to Class B in 1954, the Cuban hit in 55 straight games, finishing with a batting average of .354 (and 15 homers) for the Waco Pirates in the Big State League. The New York Times story about his hitting streak said that Mejías “can’t speak English, but his blistering bat knows the language of base hits.”[13] “What a ballplayer!” said Branch Rickey that year. “Mejias is sure to go all the way. He defends well, runs well, has a good arm and good power.”[14]

The gifted athlete faced racial and cultural obstacles. Southern segregation forced dark-skinned Latino players to live apart from the rest of the team, and Mejías – classified as a “Cuban Negro” – arrived in the United States unable to speak a word of English. He had to endure the taunts black ballplayers still faced then in minor-league ballparks of the American Southwest and South.[15] As Peter C. Bjarkman noted in his 1994 history, Baseball With a Latin Beat, “Dark-skinned Caribbean ballplayers were noteworthy when … Román Mejías first came upon the scene. … They have been truly commonplace only over the past decade.”[16]

Mejías later recalled, “I never expec’ to be so lonely in the U.S. I couldn’t eat. … I thought I would have to go back to Cuba for food. Finally, we learn to go into eating place and we go back in kitchen and point with fingers – thees, thees, these. [sic] After while, somebody teach me to say ham and eggs and fried chicken, and I eat that for a long time.”[17] Mejías’s fears that he would not be able to eat in the United States correspond well with Samuel O. Regalado’s characterization of Latino major-leaguers as having “a special hunger.”[18]

Mejías made his Cuban debut with Almendares in the winter of 1954-55. The Scorpions won the league championship and appeared in the Caribbean Series in Caracas, Venezuela. Branch Rickey had been watching Mejías in Havana, and the outfielder then made the big club in Pittsburgh coming out of spring training.[19] In fact, he was the starting right fielder on Opening Day, ahead of his fellow rookie and roommate, Roberto Clemente.[20] In his debut, on April 13, Mejías singled and walked in four plate appearances. The next day, he hit a two-run homer in the bottom of the first inning.

Clemente soon became the regular in right, however; for the year, Mejías appeared in 71 games and hit only .216. Though even his listed age was rather advanced for a prospect, one could argue that the Pirates rushed him without sufficient seasoning. Indeed, after another winter with Almendares, Mejías went back to the minors again in 1956, playing for the Hollywood Stars in the Pacific Coast League. He hit .274 during the long PCL season, appearing in 166 games, with another 15 home runs. Before the 1956-57 winter season, Almendares sent him and three other players to the Havana Rojos for Edmundo “Sandy” Amorós.

In 1957 Mejías spent much of the year in Pittsburgh, appearing in 58 games and batting .275. During most of August and the beginning of September, he played for the Columbus Jets in the International League. He led the league in RBIs for Havana with 43 during the 1957-58 winter season and won “Player of the Year” honors, even though he missed several games after an auto accident.[21] The softhearted man had swerved to avoid hitting a cat.[22]

Before the 1958 season The Sporting News wrote of Mejías, “Potentially, he has always rated highly and it was just a question of time when he’d start to blossom out.” Bobby Bragan, who’d managed Pittsburgh in 1956 and part of 1957, had also been the skipper of Almendares for several seasons. He’d seen Mejías firsthand for years and told Pirates general manager Joe Brown that Mejías was the best player in Cuba.[23]

Mejías spent all of the next two summers with the big-league club, and his games played rose from 58 in 1957 to 76 in 1958 and 96 in 1959. His batting average declined each year, but he drove in and scored more runs, a function of more playing time. He started 72 games in 1959, playing left field when Bob Skinner was injured in April, and right field in May and June when Clemente was on the disabled list. A personal highlight came in the first game of the May 4, 1958, doubleheader at Seals Stadium in San Francisco – Mejías clubbed three home runs. He hit two in a game on four other occasions, twice with Houston and twice with Boston.

About a third of the way through the 1959-60 Cuban season, Mejías went to a new team, the Cienfuegos Elefantes. After shortstop Leo Cárdenas made three errors in a game, Havana sent Cárdenas packing along with Mejías for Chico Fernández, Panchón Herrera, and Pedro Cardenal (older brother of José).[24] The Elefantes had been in a dreadful slump but turned their season around with the help of Mejías, who led the league in hits with 79. Cienfuegos won the championship that winter and then swept the Caribbean Series.

In 1960, however, Mejías was stuck on Pittsburgh’s bench in the season’s early weeks while the roster numbered 28. His only three games with the Pirates that year came within a week, on May 5, 8, and 11. He pinch-ran twice and struck out in his only at-bat, as a pinch hitter. The deadline to get down to 25 men came on May 12, and Mejías was sent to Columbus. With the Jets, he hit .278 and drove in 71 runs with a new high in homers, 16.

Meanwhile, the Pirates recalled Joe Christopher in June to be the spare outfielder. Though Mejías, too, was recalled near the end of the season, he broke his wrist in a game the weekend before he was to arrive. After the Pirates won the World Series, Mejías was one of seven players awarded a $250 payment in recognition of their short-term contributions.

Cienfuegos repeated as Cuban champion in the winter of 1960-61, but the Caribbean Series was not held because Cuba had withdrawn (the tournament remained on hiatus until 1970). Indeed, Cuba’s professional winter league ceased to exist after that season. Mejías finished his career there with 31 homers, 181 RBIs, and a .276 average in 408 games. He was inducted into the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame (in exile) in 1997.

When Mejías returned to Pittsburgh, his 1961 season played out more or less the same as 1960 had – three April games and one on May 2. Again he got just one at-bat; again it was a strikeout. Once more he spent the rest of the year with Columbus after he was optioned out on May 8. For the Jets, he lifted his annual high in homers to 21.

On October 10, 1961, Mejías got a good break: The Houston Colt .45s plucked him from the Pirates in the 1962 expansion draft. The Pirates were banking on young Donn Clendenon to fill the extra outfielder slot. They chose to leave Mejías (as well as Joe Christopher) unprotected in the draft. Each expansion club – the Mets and the Colts – selected four “premium” players for whom they paid $125,000 apiece. Mejías was one of the “first-round” selections, players whose contracts were sold for $75,000 apiece.

Not long after the expansion draft, Mejías went to play winter ball in Puerto Rico for the Ponce Leones. He left his wife and family behind in Havana – not to see them again for well over a year. The diplomatic and economic pressures of the evolving Cold War confrontation between the United States and Fidel Castro caused many such separations for Cuban ballplayers.

Houston needed Mejías, and used him, and he had the best year of his big-league career in 1962.When the fledgling club drafted the Cuban and awarded him the starting right-field position, he was determined to cash in on his opportunity. During spring training, Mejías’s five home runs and 17 RBIs carried the Colt .45s to the championship of the Arizona Cactus League. The Colts did have another Cuban at spring training, but when they broke camp, pitcher Manuel Montejo was returned to the minor leagues, leaving Mejías as the only Latino on the major-league roster.[25]

Mejías continued his onslaught against big-league pitching by hitting two three-run homers on Opening Day as the Colts won, 11-2. The Houston Chronicle described the Mejías home runs as a “double-barreled salute” to the introduction of major-league baseball “in the land of the Alamo.” Any irony that this shot was fired by a Latino ballplayer was lost upon Chronicle sports editor Dick Peebles, who focused upon pitcher Bobby Shantz’s complete-game performance. Nevertheless, Peebles did not entirely ignore Mejías, commenting that if the outfielder kept up the pace of Opening Day, he would hit 324 home runs. The editor, in a rather stereotypical fashion, noted that Mejías’ response to the ridiculous prediction was a “toothy grin.”[26]

Mejías continued to wreak havoc upon National League pitchers early in 1962. He started the season with an eight-game hitting streak, and by May 7 he had homered seven times. The press touted him as Houston’s answer to proven sluggers like the San Francisco Giants’ Willie Mays and Orlando Cepeda. Mejías entered June with 11 home runs and was leading the team in assorted offensive categories. He hit seven of those homers in cavernous Colt Stadium (360 feet down the foul lines, 420 feet in center, and 395 feet in the left and right power alleys).

After having hit only 17 home runs in six part-time seasons with the Pirates, Mejías found it difficult to account for his newly discovered power. He told the Chronicle, “I am more surprised than anyone else that I hit the long ball. In spring, I worked hard just to be patient and wait for the ball. I hit with my wrists and arms only. Before I was a line drive hitter. Not a home run hitter. The fences were a thousand miles away. Today, none of the fences are too far away. I think of the home run more because I know I can hit the ball far.” In addition to his work ethic, Mejías attributed his success to clean living. Claiming that his only vice was an occasional Cuban cigar, the athlete maintained, “Even if you are strong, sometimes you cannot do your work on the baseball field. So how can you hope to do it if you drink too much and don’t sleep enough?”[27]

A sense of modesty, along with his prolific hitting – especially at home – made Mejías a fan favorite in Houston. Media perceptions of Mejías were still framed through the lens of ethnicity, however – and his annual salary was just $12,500. The team’s Most Valuable Player was far from being the highest-paid Colt .45. The Chronicle also observed that Mejías was succeeding despite his concerns about his wife and two young children, who remained in Cuba. Mejías exclaimed, “There is not much food there, and I worry if they are eating properly.”[28]

Yet Mejías refused to complain publicly about his problems, and he continued to make the most of his opportunity to play every day in Houston. Even so, he did not make the National League All-Star team, despite standing third in the league in homers with 19. He also had 48 RBIs and was hitting .311. The players voted for the All-Stars in those days, not the fans, and they chose Mays and Clemente, along with Tommy Davis, who was also having his best year in the majors. NL manager Fred Hutchinson picked Anglo pitcher Dick “Turk” Farrell as Houston’s representative. Despite his more than respectable marks for an expansion club, Farrell expressed dismay that he was picked over Mejías. On the other hand, Mejías refused to raise issues of racial discrimination in the selection process. Though disappointed by the player balloting and Hutchinson’s choice of Richie Ashburn and Johnny Callison as reserve outfielders, he stated, “How do you like dot [sic]? Well, nothing to do but jus’ keep swinging.”[29]

But Mejías did not keep swinging as effectively during the second half of the 1962 season. Talk of the Colts finishing in the first division and Mejías attaining 30 to 40 home runs faded in the hot Texas sun of August and September. Slowed by nagging injuries and adjustments by opposing pitchers, his power numbers declined. Meanwhile, the hard-throwing and hard-partying Farrell became the darling of the Colts fans and media. The slumping Latino, Mejías, received generally respectful but certainly reduced attention.[30]

Nonetheless, Mejías ended the season with respectable numbers. He led the Colts in home runs (24), RBIs (76), and batting average (.286). He was really the only slugger on the team – the team’s runner-up in homers, Carl Warwick, had just 16. Yet when Dick Peebles compiled a review of Colts highlights for the inaugural campaign, the contributions of Román Mejías were conspicuously missing.[31]

This was still a club that needed to build, and it was not a total surprise when Mejías was traded after the 1962 season – manager Harry Craft had said that any player was expendable. But the transaction was hardly part of a youth movement by Houston management. On November 26 Mejías was dealt to the Boston Red Sox for American League batting champion Pete Runnels. By then 37, Mejías was thought to be 30 – but there was no doubt as to Runnels’ rather advanced baseball age of 34. Also, Runnels had little speed or power (just 10 homers and 60 RBIs during 1962).

So why did Houston make the trade? Marketing was a factor. While Houston executives apparently saw little potential in the Hispanic market of Texas, they were very interested in acquiring Runnels, a native of Lufkin, Texas, who resided in the Houston suburb of Pasadena. According to Houston sportswriter Clark Nealon in The Sporting News, the Colts had been trying for two years to land Runnels, a three-sport star at Lufkin High who had also attended Houston’s Rice University before turning pro in baseball. [32]

In his 1999 history of the Colt .45s, Robert Reed illustrated the role played by ethnic stereotypes in the controversial trade, arguing that Houston general manager Paul Richards was convinced that the “affable Cuban” was 39 years old rather than the “official” 30. But the transaction was risky because Mejías had “become somewhat of a fan favorite for his happy-go-lucky nature and occasionally unintentionally humorous turn of a phrase.” Reed, whose training was in journalism, seemed to have no problem with perpetuating the outdated image of the smiling, but somewhat lackadaisical, Latin ballplayer.[33]

As for Mejías, he was wished the best of luck by his former manager, Craft, who insisted, “He is a fine competitor. He carried us for the first two months of the season. … There were two reasons for his slump. He had played winter ball and started to run out of gas. Then he got hurt, missed a couple of weeks and when he got back into the lineup he couldn’t generate the steam he had before.”[34] However, Craft failed to mention Mejías’s growing concerns regarding his family in Cuba. Though the separation from his wife and two children was weighing upon his performance, Houston management showed little concern.

On the other hand, after acquiring Mejías, Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey instructed his front office to spare no expense in reuniting the ballplayer with his family. Red Sox management worked with the State Department and the Red Cross to, in the overwrought Cold War rhetoric of reporter Hy Hurwitz, “ransom the outfielder’s brood from the clutches of Castroism.”[35] Accordingly, on the evening of March 16, 1963, Román Mejías’s spring training in Phoenix was interrupted with the arrival of Nicolasa, 12-year-old Rafaela, 10-year-old José, and the athlete’s two younger sisters, Esperosa and Santa. He hadn’t seen them for 15 months. Señora Mejías had only been permitted to bring three dresses and one pair of shoes. The children were allowed only to bring the clothes they wore.[36] Following this joyous reunion, Mejías expressed his appreciation for the Red Sox organization, exclaiming, “Now, I don’t have to worry any more, and I can’t thank the Red Sox enough. I want to do everything possible for the Red Sox, and I hope very soon I’ll be helping them win the pennant.”[37]

The Red Sox had added slugger Dick Stuart the week before they’d added Mejías. They were looking forward to a real one-two punch. However, baseball reality failed to mirror the happiness of the Mejías family reunion. He had some good moments, certainly, such as the two-run double he hit in the bottom of the 15th inning on April 20 to cap a 4-3 Red Sox victory. On June 16 he hit three homers in a doubleheader, helping the Red Sox sweep Baltimore. It was “Maine Day” at Fenway Park, and Mejías received a toboggan as prize. The gift convinced him to spend the winter with his family in Boston.[38]

But Mejías first climbed above .200 only by June 22 and never got above .228 all year long. He finished the season at .227, with just 11 homers and 39 RBIs. He may have placed too much pressure on himself to show his appreciation for the Red Sox – but columnist George Vecsey argued that Mejías was another righty power hitter who pressed too hard while taking aim at Fenway Park’s inviting Green Monster in left field.[39]

After the season ended, Mejías took part in the one and only Latino players’ game at the Polo Grounds on October 12. The charity game, which benefited the Hispanic-American Baseball Federation, was the last time baseball was ever played at the ballpark before it was demolished.

Mejías’s output declined even more during his second season in Boston, with a batting average of .238, two homers, and four RBIs in just 101 at-bats – his last in the majors. However, Pete Runnels’ return to his home state was even less productive and shorter-lived. In 1963 the Texan hit only.253-2-23. After going 10-for-51 (.196) to start 1964, Runnels retired in the middle of May.

Mejías played winter ball in 1964-65, going back to Puerto Rico after a couple of seasons away. He then served as a player-coach for Boston’s Triple-A team, the Toronto Maple Leafs, in 1965. He hit .269 in 99 games with nine homers and 46 RBIs. The Boston organization sought to assign the veteran to Double-A Pittsfield in 1966, but he refused to report, and the team released him so that he could accept an offer in Japan.[40] Mejías played 30 games for the Sankei Atoms in the Central League (.288-0-4).

That was Mejías’s final season playing professional baseball. As late as 1985, however, he was still playing ball – softball, for the Orlando Cepeda All-Pro Stars. This squad – which also featured Wes Parker, Don Buford, and Dick Simpson, among other major leaguers – paid a visit to another of New York’s since-demolished ballparks, Shea Stadium. The team competed in the Los Angeles Advertising Softball League. [41] Mejías had moved to LA, where he invested some of his baseball earnings in an apartment building.

In 1999 author Jack Heyde met with Mejías as part of his series of visits with players from baseball’s “Golden Era.” Mejías talked about how Bill Mazeroski was a good friend to him with the Pirates, making him learn one new word in English each day – although the theft of his car wheels on a snowy winter day colored his feelings towards the city of Pittsburgh. Heyde concluded, “I feel very happy to have met and visited with Román. He is a man of unique pride, as evidenced by the meticulous care that he takes in maintaining his home, his property, and his flowers. … He is a genuinely friendly and appreciative person, the type one wishes the best for.”[42]

Román Mejías died in Sun City, California on February 22, 2023. He was 97.

Last revised: March 9, 2023

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

This biography was adapted by Rory Costello and Bill Nowlin from Ron Briley’s work on Román Mejías, which has a much deeper focus on his year in Houston.

“Roman Mejias: Houston’s First Major League Latin Star and the Troubled Legacy of Race Relations in the Lone Star State,” Nine, Volume 10, No. 1 (Fall 2001), 73–88.

Chapter 16 of Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003).

Books (thanks to SABR member José Ramírez for research from the Cuban sources)

Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003).

Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Ángel Torres, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997 (Montebello, California: Self-published, 1997).

Robert Reed, Colt .45s: A Six-Gun Salute (Boulder, Colorado: Taylor Trade Publishing, 1999).Newspaper and magazine articles

Román Mejías File, Baseball Hall of Fame Museum and Library, Cooperstown, New York.

Internet resources

Bill Thompson’s biographical web page on Román Mejías (http://thompsonian.info/roman-mejias.html). On this page, one may find a scanned copy of Here Come the Colts – Roman Mejias, by Joe Reichler of the Associated Press. This eight-page booklet was published in 1962 by the Houston Sports Association/Prentice-Hall, Inc.

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.japanbaseballdaily.com (Japanese statistics)

Notes

[1] Clay Coppedge, Texas Baseball (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2012): 77.

[2] Player questionnaire that Mejías completed and returned to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

[3] Román Mejías obituary, Dignity Memorial, (https://www.dignitymemorial.com/obituaries/menifee-ca/roman-mejias-11170437)

[4] Ángel Torres, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997 (Montebello, California: Self-published, 1997): 185. Translated passage: “The outfielder Román Mejías was born in the Manuelita Sugar Mill in the Las Villas Province on the 9th of August, 1930 – not in Abreus, as it reads in the Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia, or in Río Damuji, as stated in the Official Baseball Encyclopedia by Hy Turkin and S.C. Thompson. According to Who’s Who in Baseball, he was simply born in Las Villas in 1932. In the old records of the Cuban League, his birthplace was shown to be in Central Manuelita, Matanzas instead of Las Villas. All this left me very confused and I had to find Mejías where he resides in Los Angeles so he would clarify this.”

[5] In 1976 Cuba’s original six provinces were subdivided. This area is today in the province of Cienfuegos.

[6] Joe Reichler, Here Come the Colts – Roman Mejias.

[7] Mejías player questionnaire, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

[8] Torres, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997.

[9] New York Times, August 1, 1954.

[10] Les Biederman, “Bucs Found Mejias Loading Cane in Interior of Cuba,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1955: 11. This article misspelled Mejías’ first name as “Ramon” and de Arcos’ name as “Munchy D’Arcos.”

[11] Boston Globe, November 26, 1962.

[12] Peter Gammons, “Time Machine, Latin Style,” Boston Globe, April 5, 1985: 44.

[13] New York Times, August 1, 1954. The Times story ran after the streak had reached 53 games. The Los Angeles Times of March 1, 1986, is one of the publications listing the 55-game streak.

[14] Oscar Larnce, “Mejias of Waco Batting .345 for Pirate Farm Club,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1954, 35.

[15] For issues of segregation in minor league baseball, see Bruce Adelson, Brushing Back Jim Crow: The Integration of Minor-League Baseball in the American South (Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 1999).

[16] Peter C. Bjarkman, Baseball With a Latin Beat: A History of the Latin American Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1994): 6.

[17] Mickey Herskowitz, “.45s Charge Puny Attack with Missile Man Mejias,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1962: 23.

[18] Samuel O. Regalado, Viva Baseball: Latin Major Leaguers and Their Special Hunger (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998): xiv.

[19] Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999): 323.

[20] Bruce Markusen, Roberto Clemente: The Great One (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, LLC, 2001): 41.

[21] Ruben Rodriguez, “Shaw Shapes Up to Follow Jim Bunning,” The Sporting News, January 22, 1958: 24.

[22] Ruben Rodriguez, “Reds Smash Way Into Hot Pennant Fight,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1958: 20.

[23] Les Biederman, “Pirates Tab Three to Back Virdon as Middle Gardeners,” The Sporting News, January 22, 1958: 18.

[24] Ruben Rodriguez, “Marianao, Almendares Set Up Two-Club Race,” The Sporting News, December 3, 1958: 29.

[25] Jim Pendleton was the team’s only African-American until J.C. Hartman was called up at midseason.

[26] The Sporting News, April 18, 1962, and Houston Chronicle, April 11, 1962.

[27] Zarko Franks, “Mejias’ Season of Milk, Honey?” Houston Chronicle, May 30, 1962.

[28] Franks, “Mejias’ Season of Milk, Honey?”

[29] Houston Chronicle, June 30, 1962; The Sporting News, July 14, 1962; Reed, Colt.45s: A Six-Gun Salute, 112-13.

[30] Houston Chronicle, July 21, 1962.

[31] Houston Chronicle, August 28 and September 24, 1962.

[32] For the Mejías-Runnels trade, see New York Times, November 26, 1962, and The Sporting News, December 8, 1962.

[33] Reed, Colt.45s: A Six-Gun Salute, 140.

[34] The Sporting News, March 3, 1963.

[35] Hy Hurwitz, “Red Sox Worked to Rescue Mejias’ Family from Cuba,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1963.

[36] Chicago Tribune, March 17, 1963.

[37] Hy Hurwitz, “Red Sox Worked to Rescue Mejias’ Family from Cuba.”

[38] Bryant Rollins, “Toboggan Sways Him – Mejias to Winter Here,” Boston Globe, June 23, 1963.

[39] George Vecsey, “Boston’s ‘Dream’ Wall Is Really a Nightmare,” July 13, 1963, clipping from Román Mejías File, Baseball Hall of Fame Museum and Library, Cooperstown, New York.

[40] The Sporting News, July 2, 1966: 52.

[41] Jim Coleman, “Shades of Shea: Ghosts of Pennant Races Past Haven’t Changed, but Their Playing Field Has,” Los Angeles Times, July 18, 1985.

[42] Jack Heyde, Pop Flies and Line Drives: Visits with Players from Baseball’s “Golden Era” (Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing, 2004): 72-73.

Full Name

Román Mejías Gómez

Born

August 9, 1925 at Central Manuelita, (Cuba)

Died

February 22, 2023 at Menifee, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.