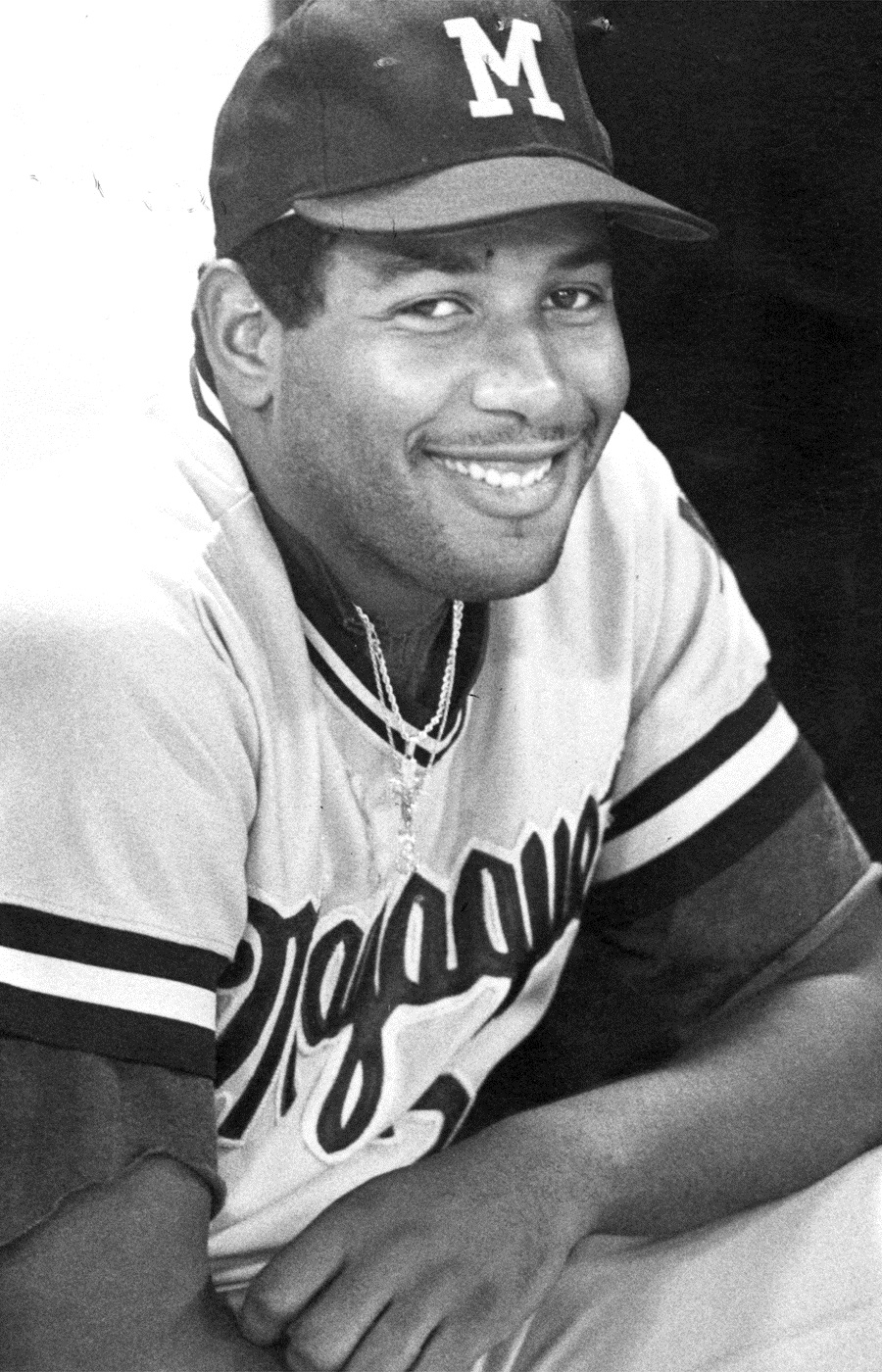

Roberto Hernández

“As a reliever, you’ve got to have amnesia. Not only with the bad days, but with the good days. You may get them out one, two, three today, but you’ve got to forget about it immediately, because that may not happen tomorrow.” — Roberto Hernandez, 20071

“As a reliever, you’ve got to have amnesia. Not only with the bad days, but with the good days. You may get them out one, two, three today, but you’ve got to forget about it immediately, because that may not happen tomorrow.” — Roberto Hernandez, 20071

“(In the 1989 Instructional League), Roberto (Hernandez) and (pitching coach) Rick Peterson worked hard like the rest of the staff always did under ‘Pete’ but, Roberto really took it a step further than most guys and made himself ‘figure it out.’ Obviously, he did, overcoming a life-threatening injury and going on to pitch for 20 years in the bigs. I love Roberto’s whole story because it’s a great one — from PR to NYC to Storrs and S.C. He did whatever it took — and was great friend and teammate along the way.

“To this day, he has always been the guy I tell people about when they ask me ‘who was the toughest guy to catch?’ Not from that day in the bullpen (when I first caught him in the Instructional League in 1989) but in games at both the minor- and major-league level when his stuff was just beginning to really explode early in his career. His fastball took off in all directions and his split was both hard and late-breaking. He threw heavy, heavy balls that could ruin your thumb if you caught it wrong, he was deceptive but what I respected the most about him was he never made excuses and was accountable.” — Matt Merullo, October 1, 2016.

Roberto Hernandez was born in Santurce, Puerto Rico, on November 11, 1964.

When he was 2 years old, his family — parents, two brothers and two sisters — moved to New York City. He grew up a Mets fan and, at age 16, even had a tryout at Shea Stadium. They wouldn’t be calling him back until more than 20 years had elapsed. As a catcher, he followed Thurman Munson of the Yankees and cried when he heard the news of Munson’s untimely death in a plane crash. Roberto was 14 years old at the time. After three years at Chelsea High School in New York, he received a scholarship to attend New Hampton High School in New Hampshire. Due to poor grades, he had to repeat his junior year, but he worked on his grades as well as his form as a catcher, and completed his secondary studies during the 1983-84 academic year.2

After high school, Hernandez went to the University of Connecticut. Although he was a pitcher in his professional career, the talented Hernandez was mostly positioned behind the plate at Connecticut in 1985. During the spring of 1985, Connecticut played a series of games in the Carolinas. Future teammate Matt Merullo remembers their first encounter: “I met Berto when he came to play UNC with the UConn baseball team. He was a freshman like me and was their starting catcher. I was DHing that day and during one at-bat, he started talking to me and I immediately liked him. I paid close attention to him and wondered what UConn was doing with him back there. He looked out of place and was young. He caught fine and had good energy but he was so tall and lanky that it took a while for him to release the ball. But when he did, it was a bazooka. Guys would be safe by a mile then have to get out of the way of a bullet.”

Hernandez starred in the first game of the Big East tournament against Georgetown. He slammed a two-run homer early on and in the 10th inning, with the game tied, really showed his mettle. He had been victimized by the Hoya running game, and three stolen bases were taken at this expense. However, in the top of the 10th, he gunned down Georgetown’s Glen Bruckner. In the bottom of the inning, he singled and was on board when Mike Pingree homered as UConn won its first game in the tourney, 11-9.3

After the 1985 season, Connecticut coach Andy Baylock was able to find Hernandez a place in the Valley League in Virginia. It was in this summer league that he pitched regularly for the first time, striking out 14 batters in his first start. He attracted the interest of college scouts and before long had a scholarship offer from the University of South Carolina at Aiken. Connecticut was not in a position to offer Hernandez significant scholarship money, and after getting approval from the UConn athletic director, Hernandez transferred to Aiken.

In 1986 at Aiken, he pitched regularly and he took a 9-2 record into the NAIA tournament in Lewiston, Idaho. When not pitching, he was the team’s designated hitter, and on May 11, 1986, he had three homers as Aiken won the district championship, and homered as his school won the regional playoffs to advance to the NAIA tournament. For the season, he wound up batting .315 with a team-high 18 homers. In the tournament, he extended his pitching record to 10-2 with a four-hit, 9-2 win over St. Francis of Joliet, Illinois, as his team finished in third place. He finished the season with 97 strikeouts in 94 innings pitched.

That season, his path once again crossed with that of Merullo. Merullo remembered, “The next fall (1985) I was jogging in the outfield just before a game against USC-Aiken and their starting pitcher was also jogging prior to his mound warm-up. We got close to each other in shallow center and I recognized him as that catcher from UConn. We had a big smile for each other and I knew he was excited to put the shinguards away and use that cannon on the mound. Being from a scouting background, I knew he had made the right career move. He just looked the part out there and the velocity was obvious without any gun. I really don’t recall that game, just meeting him again in the most unlikely place … but it made sense.”

Baseball America rated Hernandez as the 19th best player in the country going into the 1986 draft. He was the number-one draft pick (16th overall) of the California Angels in 1986 and was signed by Al Goldis.

Injuries plagued Hernandez during his first two minor-league seasons, and in 1988 he was 9-10 with a 3.17 ERA for Quad Cities in the Class-A Midwest League. He was off to a slow start in 1989 at Midland in the Double-A Texas League. After registering a disappointing 2-7 record at Midland, he was demoted to Palm Springs in the Class-A California League and eventually that season, the Angels lost interest. However, Chicago White Sox general manager Larry Himes had received positive reports on Hernandez. On August 4, the Angels traded him to the White Sox. Hernandez finished the season at South Bend in the Midwest League. The following season, he was back in Double-A, this time with Birmingham in the Southern League.

It was in the Instructional League that Hernandez once again he crossed paths with Merullo.

Matt remembered:

“Now it’s the fall of ’89, Instructional League in Sarasota. I made my debut with Chicago that April, was sent down when Fisk came back and suffered a broken hand that caused me to miss a lot of playing time. I was set to go to winter ball in the Dominican Republic after tuning up some in Florida. The new GM in Chicago was Larry Himes. He was another former catcher, turned scout then GM and had been with the Angels. He makes a deal for Roberto, who hadn’t done much in the minors but was a good ‘project.’ Roberto shows up in Instructs and just so happens to throw his first bullpen session for ‘the brass’ with me catching him. I squatted down and caught sinkers and tailing fastballs with about six guys standing behind Roberto watching every move like they were biting into gold to see if it was real. They didn’t like what they had sunk their teeth into. There wasn’t much on the ball and the delivery was way out of sync.

“Then our pitching coach, Rick Peterson, steps in and asks him to come to a set position on the mound, stare at my catcher’s mitt then ‘close your eyes and make the pitch.’ I called ‘Time out! What? You wanna catch him?’ The first pitch hissed through the air harder than anything he’d thrown, only it was off the corner of the bullpen fence about six feet to my upper left. I learned a lot that day. It was the first time I ever caught a pitcher with his eyes closed. The first of many. It was like putting a train back on the tracks. Roberto’s body was going one way and his arm was making up for it by throwing a strike with no power behind it. I didn’t even try to catch the ball but I noticed it had real life on it. It literally took off. The brass behind Peterson scratched their heads in both frustration and amazement as they witnessed a huge velocity jump in a matter of minutes. Peterson got Roberto to feel where his momentum was going and Roberto started making the adjustment to get his body under control and moving in the right direction. He was still a project of sorts but he was on his way. By the next year, he was in Double-A Birmingham and again I was catching him. I had a knee injury in winter ball that forced me back on the depth chart and I found myself playing with two kids named Frank Thomas and Robin Ventura in a league where I was an all-star two years before!”

Hernandez was invited to spring training with the White Sox in 1991, and did well. He was not sent down until the final week of spring training when Chicago decided to go with Brian Drahman as the 10th and final member of the mound staff.4

In 1991 Hernandez began the season at Triple-A Vancouver (Pacific Coast League) and posted a 4-1 record in seven starts. As early as spring training, he had felt numbness in his right hand. In June he sought medical help, and a doctor in Vancouver determined that Hernandez had blood clots. Surgery was performed by Dr. James Yao on June 4 to transfer veins from his inner thigh to his right forearm. “I was under the knife for 10½ hours one day and five hours the next. That’s the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do in my life. I had to go back under the next day because it did not take. The vein they took out of my leg and implanted in my arm did not take. It opened up and I was bleeding internally. It felt like I was on fire.”5 Although the doctor in Vancouver told him that he would never pitch again, Dr. Yao was more encouraging, saying that his chances were 50-50. Hernandez’s rehabilitation started in late June and bordered on the miraculous. He resumed pitching in July, throwing six innings in a Rookie League game in Sarasota. He then posted a 2-1 record with a 1.99 ERA in four starts at Birmingham. The key to his success was developing a slider in lieu of a curveball that had been described as “big and sloppy” by White Sox minor-league pitching coordinator Dewey Robinson.6

Late in the 1991 season Hernandez was summoned to Chicago and made his major-league debut on September 2, starting and pitching seven innings as the White Sox defeated Kansas City, 5-1. That evening the press box was full, as Bo Jackson was returning to action after surgery. Hernandez allowed only one hit and struck out four. He was simply spectacular, retiring the first 16 batters he faced and taking a no-hitter into the seventh inning before it was broken up by Bill Pecota. “At the time, I was kind of ticked. If I was going to give it up, I was going to give it up to George Brett or Danny Tartabull,” Hernandez said.7 Reflecting back on his surgery he said, “The doctors said I couldn’t come back, but I have a strong will to compete. I’ve been through a lot so I take nothing for granted.”8

His next two starts were not successful. He was knocked out in the second inning on September 7 and the third inning five days later. He spent the balance of the season in the bullpen and had no decisions after his win on September 2. His ERA ballooned to 7.80 by the end of the season.

In the offseason, Hernandez pitched winter ball for Mayaguez, Puerto Rico, which won the Caribbean World Series.

The move to the bullpen was permanent. In early May of 1992, he was sent back to Vancouver. Working exclusively in relief, he went 3-3 with a 2.61 ERA before returning to the White Sox in June. On June 21 against Detroit, Alex Fernandez started for Chicago and was done in by a five-run fourth inning. Hernandez came into the game with his team trailing 5-1, one out, and a runner on first. Hernandez stopped the bleeding and pitched through the eighth inning. By the time he left the game, the White Sox had scored five runs to take a 6-5 lead. In his 4⅔ innings Hernandez struck out seven batters and allowed only one hit as he got his second career win. Opposing manager Sparky Anderson said, “I didn’t know that kid, but he’s got a great arm.” White Sox catcher Ron Karkovice said, “I knew he felt good out there. He was throwing all three pitches (fastball, slider, and forkball) for strikes.”9

Manager Gene Lamont had a deep bullpen in 1992 and three pitchers, Bobby Thigpen, Scott Radinsky, and Hernandez, each had more than 10 saves. By season’s end, however, Hernandez had assumed the role of closer, finishing the last 15 games in which he appeared, saving nine and winning two. Knowing that his role could change day by day, he was philosophical: “It doesn’t matter who closes, we just pull for each other. Whatever role they want to use me in is fine with me.”10 From the All-Star break through Labor Day, he was 3-2 and converted five of eight save opportunities, posting a 1.44 ERA in 31⅓ innings. “I’m just having fun out there,” Hernandez said. “I’m getting ahead of hitters. Before this year and earlier in the year, I was having trouble throwing strikes and getting ahead of people.”11

Hernandez finished the season at 7-3 with 12 saves and his ERA of 1.65 was the best on the team. In 38 games from June 21 through the end of the season, his ERA was 1.53, and he struck out 63 batters in 64⅔ innings. The White Sox were in third place down the stretch and were within 6½ games of the lead when Hernandez got his eighth save on September 9. They were unable to get any closer and finished 10 games behind the first-place Oakland A’s. Hernandez was selected as the White Sox Rookie of the Year and received the Bill Veeck Newcomer Award from the Chicago Baseball Writers Association.

The next season, the White Sox won their division and advanced to postseason play for the first time in 10 years. Hernandez was a key. Manager Gene Lamont said, “He’s unfazed by the big situations. Everybody knew he had the stuff to do it. But you never really know how someone will react when you make him the (closer). Everybody can’t do it. You never know how situations will get to a guy. If he fails, how will he do next time? Every time he’s failed, he’s done fine.”12 For the 1993 season, Hernandez was in 70 games and recorded 38 saves. In the League Championship Series, which Chicago lost in six games to Toronto, Hernandez pitched in four games and was not scored on. He earned the save in Game Four as the White Sox evened the series, but Chicago lost the final two games and was eliminated.

Over the next four seasons, Hernandez became one of the preeminent closers in the league. But on occasion the road was bumpy. In the strike-shortened 1994 season, he temporarily lost his closer role when he blew consecutive saves on June 15 and 17, and was ineffective in a White Sox loss on June 20. His ERA stood at 7.33. After the three poor outings, Hernandez said, “I have to find where I was prior to this madness. It’s like everything that could happen has happened. The thing I have to do is forget about what happened and try to start over.”13 And start over he did. After missing eight games, he returned to action. In his remaining 19 appearances, his ERA was 1.74 as he saved seven games and posted a 3-1 record. For the year, his won-lost record was 4-4, but his ERA, due to the June debacle, skyrocketed to 4.91. He saved 14 games but blew six other opportunities. Twice he was taken off the hook as the White Sox came back to win.

In 1995, although Hernandez registered 32 saves, there were 10 blown saves, four during his second June swoon in as many seasons. To maintain a high strikeout ratio and be effective, he needed to spot his fastball and be effective with his breaking pitches. His 84 strikeouts in 59⅔ innings gave him a career high and all-time White Sox reliever record of 12.7 strikeouts per nine innings pitched. The record stood for 16 years until broken by Sergio Santos in 2011. Hernandez learned not to carry over a poor performance to the next day. “It’s hard for me to live with myself (after a blown save). You see your teammates go out there, battle for eight innings, and then I come in in the ninth and blow that game. I’ve learned to put it behind me for that day, but it doesn’t change the fact that I let him down.”14

In 1996 Hernandez increased his save total to 38, was named to the All-Star team for the first time, and finished sixth in the Cy Young Award voting. After blowing a save on Opening Day, he reeled off 20 consecutive saves (and one win) during 27 appearances where his ERA was 0.59. At the end of this stretch the White Sox had a 41-23 record and were within a half-game of the division-leading Indians. In his first All-Star Game appearance, he pitched a scoreless eighth inning. But his notoriety from that game had little to do with his pitching. While posing tor the team picture before the game, the platform tilted and the next thing anyone knew, Hernandez’s forearm had come into contract with the nose of Cal Ripken Jr., the guy with (at the time) 2,239 consecutive games. Ripken’s nose was bloody and broken, and “Robbie (Alomar) and Brady (Anderson) offered to get me a bodyguard when I got to Baltimore.”15 Ripken, all bandaged up, was able to start the game and later continue his streak.

On the verge of his becoming a free agent after the 1997 season, the White Sox sold Hernandez to the San Francisco Giants for the stretch drive. At the time of the trade, he was 5-1 with a 2.44 ERA and 161 career saves. After a 1996 season during which he had 38 saves and a 1.91 ERA, Hernandez had seen his salary jump to $4.62 million. But with free agency looming, the White Sox was not sure if they could keep Hernandez in the fold.

When the White Sox traded Hernandez to the Giants, he joined a contender, serving as setup man for closer Rod Beck, as the Giants won the NL West. After six years in the American League, National League audiences got to see his fastball, which was sometimes clocked at more than 100 mph. One of his victims, Todd Hundley of the Mets, said, “This guy was throwing BB’s. I don’t see anyone throwing harder than this guy.”16

Down the stretch, when Beck became erratic, Hernandez was pressed into service as the closer. On September 17, he pitched two innings to get the save against Los Angeles as the Giants pulled to within a game of the division-leading Los Angeles Dodgers. Two days later, against San Diego, he preserved the lead as the Giants, who had moved into the division lead the night before, maintained their one-game lead. On September 24 Hernandez gained his fifth win since joining the Giants. He entered the game against Colorado with the score tied 3-3 and pitched the final two innings as the Giants broke the tie and won 4-3, reducing the magic number to two. In his last appearance of the regular season, Hernandez was back in the role of setup man, pitching the eighth inning and turning over the ball to Beck as the Giants clinched the division.

Many of the Giants players had come from other organizations and Hernandez, during the stretch run, remarked, “We are a team of outcasts.” Of his role, Hernandez said, “Some situations are better for (Beck), some are better for me. I’m comfortable in the position I’m in. I’m a rover from the sixth inning until the ninth. I don’t consider it a sacrifice. I call it being a team player.”17

In 28 games with San Francisco, Hernandez went 5-2 with four saves (bringing him to 31 for the season), nine holds, and a 2.48 ERA. But in the postseason, he had little success. In Game One he entered the contest with the score tied. There were none out and two runners on base in the ninth inning. After getting two outs, he yielded a walk-off single to Florida’s Edgar Renteria. In Game Two he again entered the game in the ninth inning but was unable to record an out as the Marlins fashioned two singles, a walk, and a stolen base into the game-winning run in a 7-6 victory. In the decisive third game, he entered with his team trailing 4-2 in the eighth inning and was charged with two runs as the Giants were eliminated, 6-2.

Hernandez’s time with the Giants was short. After the season, he became a free agent and signed with the Tampa Bay Devil Rays, who were new in the American League in 1998. He set a personal high with 43 saves in 1999, blowing only four for the 69-93 Rays, and saved 101 games over three years. In 1999, he was named to the All-Star team for the second time. But despite his efforts, the Rays were years away from success, and it was time for him to move on.

Before the 2001 season there was a three-team trade involving Kansas City, Oakland, and Tampa Bay sent Hernandez to Kansas City. He toiled in Kansas City in 2001 and 2002 and racked up 54 saves, making him the first Latin player to achieve 300 saves. When he recorded number 300 on May 25, 2002, he became the 15th major leaguer to accomplish the feat. The Royals, like the Devil Rays, were not a contender and if Hernandez was to return to the postseason, it would be with another team.

That other team wound up being the Atlanta Braves. Hernandez was once again a free agent after the 2002 season and he signed with the Braves, where he became a setup man. In 2003, he appeared in the postseason for the third time. He pitched a scoreless ninth inning as the Braves lost the opener of the Division Series to the Cubs. After the Braves lost in five games to the Cubs, it was “a bad taste walking off the field, packing up, and knowing there aren’t more games.”18

Over the next three years, Hernandez made this way the Phillies (2004) and the Mets (2005). With the Mets in 2005, reunited with coach Rick Peterson, the then 40-year-old went 8-6 with four saves and an ERA of 2.58 while appearing in a team-leading 67 games. In 2006, after beginning the season with the Pirates and recording his last save, he was traded back to the Mets and returned to the postseason for the fourth time.

By that point, Hernandez was no longer a closer, but embraced his newfound role as set-up man and elder statesman. “I do miss closing, but I’ve learned to replace the satisfaction I got from that with trying to help get the lead to the closer, and also talking to and helping the young kids in the bullpen,” he said.19

How much longer would Hernandez pitch? He signed with the Cleveland Indians before the 2007 season, and that spring said, “It’s inevitable that I will have to retire some time. I’d love to play until I’m 50. [He was 42 at the time.] I may not make it, but I’m having a hell of a time trying.”20

In June 2007, when the 42-year-old Hernandez was released by the Indians, his place was secure. He was 11th in career saves with 326 and had appeared in 988 games. Was there anything left in his arm that would propel him to 1,000 career appearances. The Los Angeles Dodgers thought so and signed him on July 6. He pitched in 22 games and became one of 16 pitchers, as of 2016, to have appeared in more than 1,000 games. With the Dodgers, he was 0-2. He pitched for the last time (number 1,010) on September 25 against Colorado. He allowed three hits and a pair of runs, but he struck out his last batter, Troy Tulowitzki. It was the 945th strikeout in Hernandez’s career, and gave him a strikeout rate of 7.939 per nine innings.

Hernandez has been married to his wife, Yvonne, since his early days in the minor leagues. They have three children.

During his career and into his retirement, Hernandez was involved in his community in New York and was honored as a “Good Guy in Sports” by The Sporting News from 2000 through 2002. In his retirement, he stayed active in a number of projects, including Gloves for Kids and Project Warmth.

Just before retiring, Hernandez spoke of his resolve outside of baseball: “I think that as an athlete and coming up from New York City, and living a life as an inner-city kid, there’s a lot of things you want, but you can’t have your you can’t reach. We try to help as many people as we can, athletically or economically. Like a mentor basically. Like a concerned parent, because I have three kids of my own.”21

Last revised: August 1, 2018

This biography is included in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández.

Sources

In addition to the sources included in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, the Roberto Hernandez player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the following:

Gay, Nancy. “Artful Reliever Graces Giants,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 21, 1997: B1.

Greenville (South Carolina) News.

Interviews:

Andy Baylock — October 10, 2016.

Matt Merullo — October 1, 2016.

Notes

1 Jim Ingraham, “Hernandez Getting Better with Age,” Lorain (Ohio) Morning Call, March 15, 2007: C4

2 Tyler Kepner, “Saving the Best for Next to Last: Roberto Hernandez Now Calls the Eighth Inning His Domain,” New York Times, May 20, 2005: D2.

3 George Smith, Hartford Courant, May 18, 1985: C5.

4 “Hernandez Looking to Crack White Sox’ Starting Rotation,” Southern Illinoisan (Carbondale, Illinois), March 8, 1992: 22.

5 Murray Chass, “After Aneurysm Surgery, There’s Reason for Hope,” New York Times, May 24, 1996: B13.

6 Alan Solomon, “Changeover Sure Changed Hernandez,” Chicago Tribune, September 3, 1991: B9.

7 Solomon, “Hernandez’s 1-Hit Debut Is Royal Dazzler,” Chicago Tribune, September 3, 1991: B1.

8 Joe Mooshil, “Hernandez Pitches Three-Hitter in Debut,” Salina (Kansas) Journal, September 3, 1991: 9.

9 Solomon, “Sox Talk About Winning — and Do It,” Chicago Tribune, June 22, 1992: B3.

10 Dave Van Dyck, “Chicago White Sox,” The Sporting News, August 17, 1992: 39.

11 Solomon, “Healthy Arm Hernandez’s Idea of Happiness,” Chicago Tribune, September 4, 1992: B12.

12 Joe Illuzzi, “Chisox Count on Hernandez,” New York Post, September 3, 1993.

13 Van Dyck, “Chicago White Sox,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1994: 34.

14 Jerome Holtzman, “Sox’s Hernandez Ready to Mix It Up to Straighten Out,” Chicago Tribune, March 24, 1996.

15 Thomas Boswell, “A Little Break but Still No Bend,” Washington Post, July 10, 1996: C1.

16 Jonathan Mayo, “Hernandez Is One Giant Pickup,” New York Post, August 27, 1997.

17 Steve Marantz, “Harmonic Convergence,” The Sporting News, September 29, 1997: 31-32.

18 Todd Zalecki, “Putting It All in Words: A New Phils’ Reliever Can Always Find Pleasure in Talkin’ Baseball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 21, 2004: E7.

19 Ingraham.

20 Ibid.

21 Jayson Addcox, “Hernandez Makes Saves, On, Off Field,” MLB.com, August 6, 2007.

Full Name

Roberto Manuel Hernandez Rodriguez

Born

November 11, 1964 at Santurce, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.