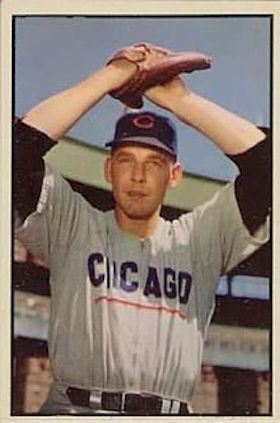

Paul Minner

Southpaw Paul Minner overcame serious injuries to his wrist and neck to transform himself from a hard thrower to a soft-tossing junkballer relying on location and control, and fashion a 10-year career in the big leagues (1946, 1948-1956). Traded by the Brooklyn Dodgers to the Chicago Cubs before the 1950 season, Minner averaged 10 wins and 192 innings per season over the next six campaigns during one of the longest stretches of futility in Cubs history. From 1947 to 1966 the North Siders finished in the second division every season and failed to produce one winning season. Minner’s career came to a crashing end when he cracked vertebrae and injured his neck on June 18, 1956, in circumstances that are not entirely clear.

Southpaw Paul Minner overcame serious injuries to his wrist and neck to transform himself from a hard thrower to a soft-tossing junkballer relying on location and control, and fashion a 10-year career in the big leagues (1946, 1948-1956). Traded by the Brooklyn Dodgers to the Chicago Cubs before the 1950 season, Minner averaged 10 wins and 192 innings per season over the next six campaigns during one of the longest stretches of futility in Cubs history. From 1947 to 1966 the North Siders finished in the second division every season and failed to produce one winning season. Minner’s career came to a crashing end when he cracked vertebrae and injured his neck on June 18, 1956, in circumstances that are not entirely clear.

Paul Edison Minner was born on July 30, 1923, in New Wilmington, Pennsylvania, a farming community of less than 1,000 residents in Lawrence County, about 60 miles north of Pittsburgh. He was the youngest of five children of Theo James Minner, a mechanic at a farmers supply store, and Rose Mae (Douthett) Minner, both native Pennsylvanians who married around 1908. Paul’s serious interest in baseball started when he participated as a 13-year-old in a summer baseball camp hosted by former Pittsburgh Pirates left-hander Wilbur Cooper, who won 216 games in his 15-year career.1 Minner was a standout athlete on the hardwood and diamond at New Wilmington High School, but also contended with injuries that marked his career. Despite suffering a broken foot as a sophomore, Minner was described as an “unusually talented pitcher [who can] flip the apple down the alley like a bolt of lightning.”2 By 1940 the hard-throwing left-hander drew the attention of baseball scouts, most notably from the Pirates and New York Yankees. Minner worked out for former big-league third baseman Freddie Lindstrom, who managed the Knoxville Smokies in the Class A1 Southern Association. “He had a brilliant fastball,” said Lindstrom.3 With approval of his parents, Minner agreed to sign with Knoxville for a $1,000 bonus after his junior year; however, Minner’s professional career was delayed one year until 1941 when he graduated from high school.

A fractured left wrist wiped out much of Minner’s first year in Organized Baseball. About two months before reporting to Knoxville’s spring training in Tallahassee, Florida, Minner suffered the injury during the basketball season. “[The broken wrist] took something away from his fastball,” remembered Lindstrom.4 Minner hurled only 29 ineffective innings and lost all four of his decisions, splitting his time with the Thomasville (Georgia) Lookouts in the Class D Georgia-Florida League and Knoxville.

With a healed wrist, the teenage 6-foot-5, 180-pouind Minner burst on the scene in 1942 with the Elizabethton (Tennessee) Betsy Red Sox, by leading the Class D Appalachian League in wins (18), ERA (1.41), and fewest hits per nine innings (6.3), and lost just twice. On July 24 he struck out 22 in a 17-inning complete-game victory over Kingsport en route to a berth on the league’s all-star team. He won two more games in the playoffs before Elizabethton was swept by Bristol in the best-of-three championship series. Newspapers at this time often referred to Minner as “Babe” before the ubiquitous “Lefty” became the more common moniker later in his career.

Just as Minner’s professional baseball career seemed to garner momentum, it was interrupted for three years by World War II. Minner was mustered into the US Army on March 2, 1943, and was originally stationed at the Army Reception Center in New Cumberland, Pennsylvania, where he pitched on the camp team.5 He rose to the rank of master sergeant in an engineering corps, but was not deployed overseas, and was stationed at Fort Lewis in Washington at the conclusion of the war.

The forces controlling Minner’s fate had shifted during the pitcher’s three years in the Army. Bob Allen, owner of the Knoxville Smokies, had transferred the club to Mobile, Alabama, in mid-July 1944 in search of bigger crowds and more money. The following year, Branch Rickey, GM of the Brooklyn Dodgers, established a working agreement with Mobile, which was reclassified from A1 to AA in the reorganization of the minor leagues for the 1946 season.

The 22-year-old Minner reported to the Dodgers spring training in Daytona Beach in 1946. “I like that skinny kid, Paul Minner,” said skipper Leo Durocher. “Something in the way he delivers the ball reminds me of (Carl) Hubbell.”6 Despite the lofty comparison, Minner had only 41 appearances and 230 innings under his belt in the minors. After a three-year hiatus away from pro ball, Minner had little chance of making the squad with veterans Kirby Higbe and Hugh Casey returning from the service and Vic Lombardi and Hal Gregg coming off productive rookie campaigns. Optioned to Mobile, Minner went 16-11 with a stellar 2.72 ERA in 235 innings for the sixth-place Bears in an eight-team league. Minner credited manager Al Todd, a former 11-year big-league catcher, with helping him refine his stride and follow-through, thereby improving his control. Purchased outright by Brooklyn in September, Minner returned to the Dodgers during an exciting pennant race with the St. Louis Cardinals in the last month of the season. On September 12 at Ebbets Field, he made his big-league debut, relieving Higbe in the third inning of a blowout against the Redbirds, yielding a hit and walk in 2 2/3 scoreless innings. In his next outing, the Chicago Cubs pounded him for four hits and three earned runs in an inning, saddling him with the loss. Brooklyn lost to the Cardinals in a two-game playoff series, the first in big-league history to determine the NL pennant winner.

In 1947 Minner remained with the Dodgers until the roster was reduced to the mandatory 25-player limit on May 15. Optioned to Mobile, Minner unexpectedly struggled, splitting his 22 decisions and posting a 3.66 ERA in 145 innings.

Minner was back at the Dodgers’ spring training in 1948, but seemed like a different pitcher. Sportswriter Harold C. Burr noted that Minner “was highly regarded in 1946,” but had since “seemed to have lost his fastball.”7 There was widespread conversation about converting Minner (a good hitter who had filled out his lanky frame to about 200 pounds) to a first baseman. Rickey, however, recognized the value of left-handed pitchers, and ultimately rejected the plan.

The cause of Minner’s sudden loss of speed and his struggles in Mobile in 1947 was probably an injury he suffered while shagging balls in the outfield with Dodgers teammate Pete Reiser. Minner dove for a catch and landed awkwardly on his neck, apparently ripping muscles and tearing ligaments. According to Chicago sportswriter Edgar Munzel, Minner “couldn’t straighten out his neck and pitched with his head cocked against the shoulder” for the next few years.8 Robbed of his fastball, he had a difficult time pitching.

Minner was optioned to Montreal in mid-May of 1948 after just one appearance for the Dodgers, but his demotion did not last long. With the Dodgers struggling and playing sub-500 ball, Minner was recalled in late June. Three weeks later he was at the All-Star Game at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis as one of the two batting-practice pitchers (the other was the Cardinals’ Ted Wilks) whom Durocher had selected to the NL All-Star squad. He picked up his first victory by hurling six scoreless innings in relief against Cincinnati in the second game of a twin bill at Crosley Field on July 17. While the Dodgers finished a disappointing third, Minner posted a 4-3 record and 2.44 ERA in 62⅔ innings.

Slotted once again for mop-up duty in 1949, Minner (3-1) logged only 47⅓ innings for the pennant winners. He etched his name in history in Game Five of the World Series against the New York Yankees on October 9. At the end of the eighth inning, at about 4:50 P.M., the lights were turned on at Ebbets Field. Moments later Minner took the mound as the first pitcher to throw under the lights in the fall classic, tossing a scoreless frame and yielding a double to Jerry Coleman as the Yankees won the deciding game of the series, 10-6. (The first night game in World Series history took place on October 13, 1971, when the Baltimore Orioles and Pittsburgh Pirates played Game Four at Three Rivers Stadium.)

One day after the conclusion of the World Series, Minner was sold along with first baseman Preston Ward to the Chicago Cubs for an estimated $100,000. The tall lefty reported to the Cubs’ spring-training facility on Catalina Island widely anticipated as a “regular starter” for a club whose staff finished last in team ERA in 1949.9 Skipper Frankie Frisch, who had taken over from the affable “Jolly Cholly” Grimm after 50 games the previous season, vowed to mold his team into a disciplined group, but the results were almost the same. Other than two holdovers, right-hander Bob Rush and southpaw Johnny Schmitz, the staff lacked depth. Minner began the campaign in the bullpen, then struggled in his first attempt as a starter (6.55 ERA in four starts). He got another shot in late June and proved his worth, reeling off four consecutive complete games, including three straight victories, to secure his position. Described by Edward Burns of the Chicago Tribune as a “gent of considerable poise,” Minner tossed a career-best 13-inning complete-game victory against Boston on August 5 at Braves Field en route to an 8-13 record and 4.11 ERA in 190⅓ innings for the seventh-place Cubs.10 Though never considered a strikeout pitcher, Minner averaged 4.7 whiffs per nine innings, good for seventh best in the league.

Frisch pointed to young hurlers on his staff such as Rush, Minner, Warren Hacker, and hard-throwing second-year right-hander Johnny Klippstein as reasons for optimism for the 1951 season. “If we get a couple of those kids going,” he mused, “we’ll be in the first division.”11 Schmitz had been traded away in the offseason, making Minner the primary southpaw on the club, a distinction he’d hold for the remainder of his tenure with the Cubs. Frisch handled his staff the way his mentor, John “Little Napoleon” McGraw, did when the Fordham Flash anchored the keystone sack for four consecutive pennant winners (1921-1924) for the New York Giants, and then four more for the Cardinals. Frisch eschewed a set rotation, and as Chicago sportswriter opined, “virtually pulled his starters out of a hat.”12 Consequently, pitchers struggled to find a rhythm, as eight hurlers started at least 11 games. Minner tossed a seven-hit shutout against Cincinnati in his debut, the home opener at Wrigley Field, but wins were few and far between. First baseman Phil Cavarretta replaced Frisch as skipper in midseason, but the North Siders continued their free-fall, finishing in the cellar. Minner had an unsightly record, six wins and 17 losses (tying for the NL lead in that dubious category), yet was probably the most effective hurler on the staff. While the woeful Cubs offense scored three runs or fewer in 15 of Minners’s losses, the southpaw paced the staff in ERA (3.79), complete games (14), and shutouts (3), including a two-hitter against Cincinnati.

As the Cubs began their quest for a winning season in 1952, beat reporter Edgar Munzel anticipated big improvements from the hurling quartet of Rush, Minner, Klippstein, and Hacker, despite their cumulative record of 23-35 in ’51.13 Though Minner was roughed up in the season opener against Cincinnati, lasting only 4⅔ innings, he got off to a strong start. He had worked with pitching coach Charlie Root, the former North Side hurler who as of 2016 still held the club record with 201 victories, to change his stride and follow-through, and the results were immediate. In his last start before the All-Star break, he tossed a two-hitter to defeat the Reds at Wrigley Field, 5-1, to set a career high with his ninth victory against just three defeats, and lower his ERA to 2.89. In his one legitimate shot at a berth on an All-Star team, Minner was snubbed by the Giants’ Leo Durocher, who skippered the NL squad.

“Minner’s radical reversal of his performance of the past two years with the Cubs is almost unbelievable,” gushed Munzel.14 Minner had a simple explanation for his success. “I’m just getting smarter,” he said. “I’m winning because I finally got it through my punkin head I couldn’t throw the ball past hitters.”15 Never having regained his fastball after his neck injury, he transformed himself into a crafty pitcher, relying mainly on changing speeds, breaking stuff, movement, and control for his success. Four times he placed in the top ten for fewest walks per nine innings, and posted a career-best mark of 1.8 walks per nine innings in 1953. He claimed he patterned his game after those of Cincinnati’s Ken Raffensberger and Brooklyn’s Preacher Roe, neither of whom had a blazer, but were nonetheless successful. “I now use three different speeds with my fastball and two on the curve,” said Minner.16 The hard-throwing Rush overpowered hitters, but “Minner outsmarts them,” opined Munzel.17

After an impressive first half in 1952, Minner imploded after the All-Star break. He lasted only 43⅔ innings with a 7.42 ERA in his next 10 starts. Sportswriter Edward Burns was concerned about how the 29-year-old would respond to the beatings. “He is as conscientious as any pitcher on the staff, and perhaps the most sensitive,” wrote Burns. “His morale, more than his pitching, needs rebuilding.”18 Minner made only three starts over the last month of the season, winning each, including a shutout against the Cardinals on September 29. That game was noteworthy in that Stan Musial secured his sixth of seven batting titles, beating out the Cubs’ Frank Baumholtz (.336 to .325); Musial, a former minor-league hurler, also made his first and only big-league pitching appearance in that game, facing only one batter, Baumholtz, who reached on an error. Minner (14-9, 3.74 ERA in 180⅔ innings) joined Rush (17-13; 2.70) and Hacker (15-9, 2.58) in leading the Cubs to a .500 record (77-77) and a fifth-place finish.

After offseason rumors that Minner would be traded back to Brooklyn proved to be false, Minner reported late to the Cubs’ camp in Mesa, Arizona, following a holdout. It was another dismal season for the North Siders. The weak-hitting Cubs were outscored by more than 200 runs and finished in seventh place despite the acquisition in early June of slugger Ralph Kiner in a blockbuster trade with Pittsburgh. Minner (12-15, 4.21 ERA in 201 innings), Hacker (12-19, 4.38 ERA) and Rush (9-14, 4.54) anchored a staff that finished seventh in team ERA. Hacker became the third Cubs hurler in four years to lead the league in losses, tying Pittsburgh’s Murry Dickson, and joining Minner (1951) and Rush (20 losses in 1951) in that unflattering distinction.

Cubs players got a jolt during spring training in 1954 when popular player-manager Phil Cavarretta became the first manager in big-league history to be fired during spring training, after the Cubs lost 15 of 20 exhibition games. He was replaced by former Cubs third sacker “Smiling Stan” Hack, who tabbed Minner to open the season at Sportsman’s Park. Described by St. Louis sportswriter Bill Broeg as the Redbirds’ “full-blown nemesis,” the soft-throwing junkballer tossed a six-hitter to win, 13-4, his sixth victory in his last seven decisions against St. Louis.19 He also whacked a homer and drove in three runs. Minner beat the Cardinals four more times, including three complete games, before a losing to them in his final start of the season. In a career-high 29 starts among his 32 appearances and a career-best 218 innings, Minner split his 22 decisions and posted a sturdy 3.96 ERA for the seventh-place Cubs.

For most of his career, Minner spent the offseason in his hometown of New Wilmington. He married local resident Eileen Belle Hoover on August 20, 1944, while serving in the Army. They had one child, Jon. According to The Sporting News, Minner had numerous offseason jobs, including selling cars, managing a bowling alley, and working for a government census office. By the mid-1950s, the Minners had relocated to Evanston, a northern suburb of Chicago, where Paul sold insurance.

Minner tossed a complete game to beat St. Louis 14-4, in the home opener at Wrigley Field in 1955. Plagued by arm pain for much of the season, he nevertheless improved his career record to 14-2 against the Redbirds by winning his fourth consecutive decision of the season against the Cubs’ archrivals on July 2, and improving his season record to 7-3. The number-four starter behind Rush, Hacker, and offseason acquisition Sam Jones (who continued a Cubs’ tradition by leading the circuit with 20 losses), Minner made only 10 more starts, finishing with a 9-9 record and robust 3.48 ERA in 157⅔ innings.

“Now that Eddie Lopat is out of the big leagues,” wrote Edward Prell in the Chicago Tribune prior to spring training in 1956, “the Cubs are ready to nominate their own Paul Minner as the leading ‘junk man’ of the majors.”20 After tossing what proved to be the 64th and final complete game of his career to defeat Cincinnati in his first start of the season, Minner went into a tailspin. He was pummeled for 42 hits and 29 runs (27 earned) in his next 31⅓ innings before picking up an ugly victory against the Giants at the Polo Grounds despite yielding 11 hits and five runs in 6⅔ innings on June 12. Six days later he reportedly fell in a bathtub in his New York City hotel, suffering a concussion and hurting his back and neck. Still unable to pitch a week after the incident, Minner was re-examined and doctors discovered a cracked vertebra. His neck was placed in a cast for an expected two to three months. It was widely reported that the injury re-aggravated Minner’s initial neck problems suffered while a member of the Dodgers. With his career in jeopardy, rumors emerged in Chicago that the mild-mannered Minner’s injury was the result of a scuffle with teammates, though Minner denied the reports.21

Though neither Minner nor his teammates were punished, at least not publicly, following the incident, the injury effectively ended Minner’s pitching career. He did not pitch again in 1956 and was given his unconditional release the day after the season ended.

Minner and his family moved back to the New Wilmington area after his release from the Cubs. He contacted the Pirates and attempted a brief comeback in 1957, but was released during spring training. In his 10-year big-league career, he went 69-84 with a 3.94 ERA in 1,310⅓ innings. He found most of his success against three teams, going 21-8 against the Cardinals, 16-14 against the Reds, and 16-16 against the Pirates. Minner also handled the bat well, hitting .219 (98-for-447) with 29 extra-base hits, including six round-trippers, and 43 runs batted in. In 1954 he knocked in a career-best 14 runs on just 13 hits.

After baseball, Minner inaugurated a long, successful career in the insurance business, retiring from the Pennsylvania Insurance Department in the 1980s. In 1986 he was inducted into the Lawrence County Sports Hall of Fame. He died at the age of 82 on March 28, 2006, in Lemoyne, a suburb of Harrisburg. A memorial service was held at Parthemore Funeral Home in New Cumberland, after which Minner’s remains were cremated.22 His wife of 62 years, Eileen, had died earlier that year.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Minner’s player file and questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 “Minner, Dodgers’ Rookie, a Threat From Right to Left,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 17, 1946: 11.

2 “Ramblings Around World of Sport,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, March 29, 1929: 14.

3 Arch Ward, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1954: D1.

4 Ibid.

5 Minner’s military questionnaire in his player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

6 “Durocher Places Accent on Youth,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 5, 1946: 15.

7 The Sporting News, February 25, 1948: 17.

8 The Sporting News, July 4, 1956: 15.

9 Irving Vaughn, “Cubs Still Plague Grimm; Beat His Dallas Lads, 7-3,” Chicago Tribune, April 8, 1950: A1.

10 Edward Burns, “Sox Lose, 8-7; Cubs Defeat Dodgers, 6-4,” Chicago Tribune, July 14, 1950: B1.

11 Associated Press, “Training Camp Briefs,” Terre Haute (Indiana) Tribune, March 5, 1951: 10.

12 The Sporting News, August 15, 1951: 10.

13 The Sporting News, April 16, 1952: 3.

14 The Sporting News, July 16, 1952: 24.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 The Sporting News, September 3, 1952: 12.

19 Bob Broeg, “Unruly Chicago Guests Break Up Cards’ Housewarming Party,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 14, 1954: 36.

20 Edward Prell, “Minner, New Majors Top ‘Junk Man,’ Signs,” Chicago Tribune, January 11, 1956: C1.

21 The Sporting News, August 1, 1956: 14.

22 Paul E. “Lefty” Minner Obituary, New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, March 30, 2006. ncnewsonline.com/obituaries/paul-e-lefty-minner/article_cbae77e8-ab33-5c22-8476-91b6438a1914.html.

Full Name

Paul Edison Minner

Born

July 30, 1923 at New Wilmington, PA (USA)

Died

March 28, 2006 at Lemoyne, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.