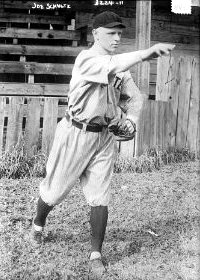

Toots Shultz

From 1906 to 1911, right-handed pitcher Wallace Luther “Toots” Shultz was the most sought-after student/athlete in baseball. From his days at prep school through his college days at the University of Pennsylvania he was pursued by his hometown Pittsburgh Pirates, the Philadelphia A’s and Phillies, both Boston teams, and the New York Highlanders. In 1911, when Shultz finally signed with the Phillies, his contract was the richest ever given to a college player heading to the major leagues. He was expected to be another Christy Mathewson, who had attended Bucknell University before starring for the New York Giants.

From 1906 to 1911, right-handed pitcher Wallace Luther “Toots” Shultz was the most sought-after student/athlete in baseball. From his days at prep school through his college days at the University of Pennsylvania he was pursued by his hometown Pittsburgh Pirates, the Philadelphia A’s and Phillies, both Boston teams, and the New York Highlanders. In 1911, when Shultz finally signed with the Phillies, his contract was the richest ever given to a college player heading to the major leagues. He was expected to be another Christy Mathewson, who had attended Bucknell University before starring for the New York Giants.

Toots Shultz was born on October 10, 1888, in Homestead, Pennsylvania, across the Monongahela River from Pittsburgh. He was the fifth of six children born to John and Jennie (Jefferries) Shultz of nearby McKeesport. He had three older brothers, including twins Harry and James, who were six years older and were well known local ballplayers. But baseball was a pastime in the Shultz family, not an occupation. Life centered on National Tube Company in McKeesport, the maker of the first steel pipe manufactured in the United States (and later acquired by US Steel). John Shultz was a machinist there; his older sons all followed in his footsteps as draftsmen and machinists at the plant; and Toots was expected to join them.

At two Pennsylvania prep schools, first at Shady Side Academy, then at Mercersburg Academy, Toots built a reputation as a great young pitcher. While pitching with Mercersburg he beat the Princeton baseball team twice, in 1906 and in 1907. As a member of the Pittsburgh Collegians he spent his summers competing against college, minor-league and Negro League players, starting at the age of 14. When Shultz graduated from Mercersburg in 1907, his next move was closely followed by the national sporting press.

In spite of multiple offers from major-league teams, Shultz decided to pursue studies at the University of Pennsylvania. When he entered Penn he majored in art, but he switched to mechanical engineering to prepare himself for a job with National Tube Company. Still, it was Shultz’s pitching for Penn that kept grabbing all the headlines and that drew the attention of big-league scouts and managers. And his schoolwork was not keeping pace. He struggled to maintain academic eligibility to pitch for Penn in 1909 and 1910. Before the 1911 season Shultz failed his tests and was asked to leave the university. He tried to persuaded the faculty to allow him to stay and to switch his major back to art, but they refused and his career at Penn came to an end. Finally, after all those years of pursuit, he was ready to sign a major-league contract.

Shultz still had to convince his father, who had a factory job ready for him in McKeesport. He asked for just one year in baseball, promising to settle in down in business after that. He then proceeded to sign a two year contract with the Philadelphia Phillies, for the then princely sum of $3,500 per year. Shultz was in such demand that he was able to eliminate from his contract the standard (and notorious) ten-day clause that would allow the Phillies to release him if he failed.

Toots was 22 years old when he went south to Alabama for spring training with the Phillies. At 5-feet-10 and 175 pounds, he had made his name not only as a pitcher but also as a hitter and in the field during his school days. But he got off to a poor start in the big leagues, losing three games, winning none, and posting an ERA of 9.36. He struggled with control and hit four batters in only 25 innings. On May 30, 1911, the Phillies decided it was time to make some radical changes and removed seven players from their major-league roster. Shultz was sent to the Buffalo Bisons of the Class A Eastern League for seasoning. He was paid his full $3,500 salary to pitch in the minors.

In Buffalo Shultz worked regularly, winning 11 games and losing eight. Manager George Stallings declared at the end of the season that he had made a pitcher out of Shultz. In the fall the Phillies played a series against Cuban teams. Star pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander was not with the team. Toots rejoined the Phillies and lived up to Stallings’ claim in the series, pitching in six of the nine games, and winning five times. The Phillies lost all three of the games in which he did not pitch. He had reportedly taken to relying heavily on the spitball.

Shultz spent the winter with a Buffalo teammate, catcher Bill Killefer, in Michigan. Killefer said they would do some hunting and promised they would show up for 1912 spring training in magnificent shape. They may have been in shape when they arrived at the Phillies’ camp, but Shultz frustrated manager Charley “Red” Dooin by putting on 15 pounds during spring training, and apparently annoyed his teammates by dressing formally for dinner every night.

Though he excelled at the dining table, Shultz struggled on the mound. In a preseason batting practice session he hit teammate Sherry Magee with a “swift inshoot,” breaking Magee’s wrist.i In four innings of work in an exhibition game against the Philadelphia Athletics, he gave up 12 hits and two walks and hit two batters, putting A’s outfielder Bris Lord out with a bruised wrist on a pitch similar to the one that had injured Magee. Ben Shibe of the A.J. Reach Company was experimenting with a softer baseball for youth baseball, and Toots joked, “That’s the kind of ball for me to pitch. I could hit all the Magees and the Lords in base ball and not break a bone.”ii

Shultz eventually got his first and only major-league win that year. But he was used mostly as a “rescue” pitcher, which was not considered a glamorous job in 1912. And he didn’t do much rescuing, posting a 1-4 record. The Phillies made Shultz an offer for 1913 at a much lower salary, and an unhappy Shultz talked a little too much among his teammates about it, which upset manager Dooin. Shultz commented that he could make more money selling real estate than pitching for the Phillies. Manager Dooin replied that the Phillies could make more money in the grain and hay business than by having Shultz pitch for them.iii So, having invested $7,000 in one win, the Phillies were ready to let him go.

Given the high expectations (and high salary) that came with Shultz to the Phillies, there was much discussion of why he failed. Shultz blamed a dislocated knee that he said bothered him both years. Manager Charley Dooin questioned Shultz’s work ethic. When Shultz was sent to Buffalo in 1911, Dooin had said he was tipping his pitches, and also accused him of “indifference.”iv When he was cut in 1912, Dooin criticized Shultz’s training habits and his 15 pounds of spring weight gain. Teammates questioned his heart, suggesting that as a pitcher Shultz had the goods and was unhittable in pregame practice, but was unable to deliver in real games. “If baseball was only played in mornings Shultz would be the greatest pitcher in the world,” said one teammate.v

Toots played ball that winter in San Diego, California. The Phillies sold him to the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League in December. Shultz expressed the hope that playing 1913 in “slower company” would help him regain his form. But the company wasn’t slow enough. In the spring there were reports that his knee still bothered him, and on June 21 Sacramento released him, citing a familiar problem – failure to get into condition. The next day Shultz was engaged in an early-morning poker game in a hotel room with some former teammates when the police showed up to break up the game. The players hid the chips under the mattress and the cards in a dresser drawer in order to avoid being arrested for an illegal poker game.

Shultz was picked up by the Vancouver (British Columbia) Beavers of the Class B Northwestern League and finished 1913 there. He was not impressive – he won one and lost two for the Beavers – but an optimistic Hugh Jennings bought his contract for $4,000, hoping Toots could be productive for his Detroit Tigers in the 1914 season.

Shultz wintered in Laguna Beach, California, looking forward to another shot at the big time. He showed up with a “corking” knuckleball added to his pitching repertoire, but he wasn’t with the Tigers for long. On April 10 Detroit released Shultz to Providence of the International League.

At this point it might have been expected that Toots would give up on being a ballplayer. His father certainly would have welcomed him home to McKeesport and a job at National Tube Company. His commitment to baseball and his conditioning were regularly questioned by managers, teammates, and the press. But on the other hand, Toots had also shown a love of the game. As a schoolboy he always played with the Pittsburgh Collegians in the summer. As a pro he found opportunities to get into fall and winter games. In additional to baseball, he enjoyed the manly pursuits with his teammates – hunting, poker, billiards, golf, and attending boxing matches. It turned out that Toots was nowhere near ready to give up the life of a ballplayer for a factory job. He reported to the Grays, after insisting that he be paid at the rate he had agreed to with Detroit.

Maybe that dislocated knee had healed, or maybe Toots just finally buckled down. In 1914 in Providence he won 19 and lost 11. He was only the third best pitcher on the Grays’ staff, not because he didn’t pitch well but because he was on a pitching staff with Babe Ruth and Carl Mays. He settled in as a fixture for Providence, winning 18 games in the 1915 campaign. He stayed with the Grays until World War I interrupted his career in 1918. In spite of some good pitching in the competitive International League, no major-league teams came calling.

The best-known events of Shultz’s career occurred in Providence. They are well known mostly because he was a teammate of Ruth, so the story was told in Robert Creamer’s definitive biography of the Sultan of Swat, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life. Shultz’s parents and grandparents were all born in Pennsylvania, but he was proud of his German heritage. When the World War broke out in Europe in 1914, he strongly supported the German side, leading to a new nickname for Shultz – “Kaiser.” He took considerable ribbing from his teammates, and when the French won a decisive victory over the Germans, Shultz was sent numerous copies of the newspaper accounts. In response, he took all the newspapers, wrapped them around a brick, and sent them to infielder Matty McIntyre, postage due. McIntyre had been expecting a package, so he paid the exorbitant 48-cent postage bill only to find that the Kaiser had gotten his revenge.

The rough treatment spread beyond Shultz’s teammates. In a game in Toronto in 1915 he was asked to pinch-hit. When his name was announced, according to Shultz, the crowd was worked up. Canada was already at war with Germany and did not appreciate his German loyalty. As he came up to hit against Toronto pitcher Bill McTigue, Shultz said, “You ought to have heard the row. Kill ’im. Kill the German. Hit the Hun in the eyes, McTigue. Knock ’is bloody brains out, McTigue.” McTigue promptly hit Shultz on the arm with the pitch, and crowd was, as Shultz described the scene, “as joyous as if a Canadian regiment had captured the Kaiser.” Shultz professed to be happy just get on base, believing that if he had gotten a hit “there would have been one Pennsylvania Dutchman less in this world.”vi

On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. A month later “Kaiser” Shultz registered for the draft, and he was classified 1A. In February of 1918, at the age of 29, he enlisted in the Navy and reported for duty in Newport, Rhode Island. His training regimen had not improved. The Pawtucket Times suggested that he chose the Navy because a “fellow as rotund as himself would not have much room in the trenches.”vii In any case, for both Shultz and the US military, it made more sense for a man with German sympathies to serve in Rhode Island than on the front lines in Europe. He was a machinist’s mate first class, which must have made the machinist Shultzes back home in McKeesport proud. But as always, Shultz found a way to be more ballplayer than machinist. He was the pitcher for the Newport Naval Station nine, whose schedule included more than 20 games against teams from other military bases and New England colleges as well as and the Boston Braves and Cleveland Indians.

Shultz’s Navy service ended on February 13, 1919. In April Providence sold his contract to the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League, so Shultz headed west to resume his baseball career. In spite of having kept in practice in the Navy, he was pounded by PCL hitters, and Seattle let him go in early June. But Wade “Red” Killefer, brother of Jim Killefer, who was Shultz’s friend and catcher in Buffalo and Philadelphia, was managing the PCL’s Los Angeles Angels and decided to give Shultz another shot. Toots did well enough in his Los Angeles stint to at least inspire some hope, and he was invited back for 1920.

That fall Shultz went hunting for deer and bear in Oregon with some fellow PCL ballplayers, and he “kept in shape” that winter on the golf course. The Portland Oregonian reported that he had worked hard and weighed less than he had at any time since leaving college.viii But he was hit hard in three appearances with the Angels, and they let him go. His rights were sold to Joplin of the Western League.

Toots instead headed to California’s Central Valley to pitch in the “outlaw” San Joaquin Valley League. He was joined by Al Bartholemy, a catcher who had also been let go after a brief 1920 stint with Los Angeles. Together they formed the battery for the Dinuba Sun Maids (it was raisin country). They also were partners in a combination Brunswick billiard parlor and confectionery store, an odd sort of business that was a product of Prohibition and possibly a front for other activities. The league played on Sundays and holidays, so a pitcher like Shultz would work just about every inning of every game, with a regular job during the week to pay the bills. The league featured quite a few former major-league and Pacific Coast League ballplayers, and a few baseball outlaws, most notably Chick Gandil with the Bakersfield Elks in 1920 (before he was an official outlaw) and Dutch Leonard with the Fresno Tigers in 1922 and 1923.

Shultz was no longer a full-time ballplayer. When he registered to vote as a Republican in Dinuba in 1922 he indicated that his occupation was “merchant.” But he played for Dinuba longer than he had played anywhere else in his career. Shultz was the primary pitcher for Dinuba from 1920 through 1922. He still had a tendency to hit batters with his pitches. In August of 1922 the shortstop for the Hanford Kings, a player named Brown, thought Toots was trying to bean him and threw his bat at Shultz. A harmless fight ensued. In 1923 former New York Yankee pitcher Ray Keating took over the pitching duties for the Sun Maids and Shultz spent two seasons in the outfield. He had always had a reputation as a good hitter and fielder, even when he struggled on the mound.

By the summer of 1925 Shultz had made his way back home to McKeesport. Not much had changed there. He moved into the family home with his parents, his older twin brothers Harry and James (both single and still working at National Tube Company), and his single younger sister, Bessie. Shultz’s oldest brother, Frank, had married and was living with his wife in McKeesport and working at National Tube. Only his older sister, who had married and moved to Chicago, had left McKeesport.

Toots was still living in the family home with Harry, James, and Bessie in 1940. In about 1941 he married Anna B. Caves, who worked as a stenographer at the Tube City Brewing Company. Toots took a new job with the Pennsylvania State Highway Department, for which he worked as a foreman until his death. On the morning of January 30, 1959, Wallace Luther Shultz died of a heart attack in McKeesport at the age of 72. He was the first of his siblings to pass, and he was survived by his wife. He was buried at McKeesport & Versailles Cemetery.

Sources

The famous story of Shultz supporting Germany in World War I and the ensuing practical jokes was found in Robert Creamer’s Babe: A Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1974), 97-98, and in Diamonds in the Rough: The Untold History of Baseball by Joel Zoss and John Bowman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 88.

Information about the series with Havana in the fall of 1911 was found in Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 by Jorge S. Figueredo (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2011).

Since there is no existing account of Shultz’s life, I looked at about 400 newspaper articles from papers across the country to develop his biography. The contemporary accounts found in Sporting Life (from the LA84 Foundation) and in newspapers at Genealogybank.com, NewspaperARCHIVE.com, Google News Archive, and Chronicling America helped to uncover the winding career path of Toots, provided game accounts and gave access to contemporary commentary on his career by managers, players, and columnists.

Accounts of Shultz’s career in the San Joaquin Valley League are from the above sources and from clippings from the Dinuba Sentinel in the collection of the author.

Shultz’s Hall of Fame folder provided an especially helpful obituary and a certificate of death.

Ancestry.com provided the Shultz family background and general biographical information, especially the US Census 1880-1840, World War I and World War II draft registrations, Pennsylvania Veterans Burial Card and California Voter Registrations for 1922 and 1924.

Minor-league statistics come from SABR’s minor-league database at baseball-reference.com. Shultz’s various stints were not all together under one player ID, but they were all located, and the keepers of the database notified as to which should be credited to Toots.

Penn’s brief online biography of Shultz at http://www.archives.upenn.edu/people/1800s/shultz_wallace_luther.html helped me to outline his life at the outset of my research and know where to look for him in my further research.

Notes

i Reading Eagle, May 6, 1912.

ii Sporting Life, June 22, 1912.

iii The Oregonian, Portland, January 26, 1923.

iv Sporting Life, June 24, 1911.

v New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, February 11, 1913.

vi Pawtucket (Rhode Island) Times, March 29, 1916.

vii Pawtucket Times, February 23, 1918.

viii The Oregonian, March 21, 1920.

Full Name

Wallace Luther Shultz

Born

October 10, 1888 at Homestead, PA (USA)

Died

January 30, 1959 at McKeesport, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.