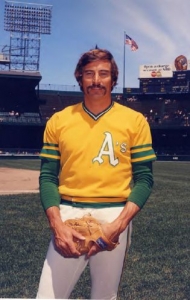

Bob Locker

Bob Locker threw 879 innings in the major leagues. His career earned-run average was 2.75. Pitching for the White Sox in the mid-1960s, he was an ace for a bullpen that led the league in ERA for four straight years. Oakland manager Dick Williams deployed him as his designated rally-killer in 1971, when the A’s won 101 games, and 1972, when they became world champions. And yet Locker saw himself as a player of very limited ability. “I had no depth perception, I couldn’t field, I couldn’t hit,” he said. “My job was to work at avoiding trouble, on not screwing it up for the other guys.”1

Bob Locker threw 879 innings in the major leagues. His career earned-run average was 2.75. Pitching for the White Sox in the mid-1960s, he was an ace for a bullpen that led the league in ERA for four straight years. Oakland manager Dick Williams deployed him as his designated rally-killer in 1971, when the A’s won 101 games, and 1972, when they became world champions. And yet Locker saw himself as a player of very limited ability. “I had no depth perception, I couldn’t field, I couldn’t hit,” he said. “My job was to work at avoiding trouble, on not screwing it up for the other guys.”1

The first child of Henry and Northa Locker, Robert Autry Locker was born on March 15, 1938, in George, Iowa. The Lockers grazed cattle and grew corn on pasture they owned at the edge of town. When he could, Locker played baseball as a child, but he spent much of his after-school time chopping corn. He adored his mom, “an absolute saint. She’s the reason I turned out reasonably well.”

Locker attended his mother’s alma mater, Iowa State University, where he played baseball for legendary coach Cap Timm. Locker would credit Timm, who coached the Cyclones for over 30 years and whose name graces the team’s ballpark, as the person who taught him the most about baseball. In high school Locker had been “a typical farmboy, trying to throw the ball through a brick wall. I had very little science and finesse. I was trying to impress myself, throwing harder and harder.” Under Timm’s guidance, Locker worked hard on his mechanics and grips, shortened his stride, and learned to hang onto the ball longer before releasing a pitch. When he finally put it all together, Locker developed a major-league-caliber sinker. “Those adjustments, coupled with my inflexible fingers, allowed me to throw the sinker with full fastball velocity,” he said.

Tall (6-feet-3) and lean (200 pounds), and coming from a heavily scouted program, Locker was courted by three major-league organizations by the end of his fourth year at Iowa State. “The White Sox, Yankees, and Orioles made me offers,” he recalled. “Even though the Yankees offered $12,000, I accepted the White Sox offer for $10,000.” His rationale: By the time he was ready for the majors, Early Wynn and others would be retiring, so Locker decided to take short money in exchange for the faster path to the majors.

Locker pitched briefly in the low minors in 1960 before returning to school to finish his geology degree, and in 1961 he joined the Lincoln Chiefs, Chicago’s affiliate in the Class B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League. He led his team in ERA (2.57) and wins (15), and his 228 innings were most in the league. He spent 1962 and 1963 out of baseball fulfilling an Army ROTC service commitment. On leave in 1962, Locker married Judy Swalve, and in 1963 they had their first child. When Locker returned to baseball in 1964, Chicago rushed the 26-year-old to the Indianapolis Indians of the Pacific Coast League and he picked up where he left off. He led Indians starters in innings (226), ERA (2.59), and wins (16). He struck out 178 and walked only 57, a preview of the control he would have throughout his major-league career.

When Locker reported to his first major-league camp, in February 1965, he had military experience, a college degree, and a family. He arrived in boot-camp shape. He wore a weighted vest and spent much of his time doing finger exercises. He carried index cards everywhere he went so he could keep notes on hitters and umpires. “I keep tabs on just how umpires call pitches on me,” he told a sportswriter. “I want to remember if they will give you that low strike or whether they’re high-ball umps, whether they are good on inside or outside pitches. Someday, in a tight situation, it may be important.”2 Small things, perhaps, but Locker, assiduously self-critical, felt he needed every edge to close the gap between his talent and everyone else’s.

Locker made the team but not as a starter. In the minors he had complemented the sinker with a changeup, a nickel-curve, and a fastball. But the White Sox were so impressed with the explosive sinker that they sent him to the bullpen and — in not so many words — ordered him to forget the rest of his repertoire and stick to the sinker.

“There are two kinds of sinker,” Locker explained. “One is a roll-over sinker — Tommy John had one of those — a predictable pitch. I had a smothered sinker, which is a lot like a knuckleball. It’s hard to predict. I had to fight it every day, every pitch. But when everything was right the ball had some pretty wicked downward movement. It offset my liabilities. You know that if you throw it and the guys get a couple of singles off it, you keep throwing it and they’ll eventually hit it at someone and you’ll get a double play.”

In Ball Four Jim Bouton wrote that he heard rumors the White Sox kept the balls so cool and damp that they mildewed.3 What’s more, Locker remembered that the team kept the infield wet.3 “Managers really want you to get the ball on the ground. The Sox liked the idea that I was a groundball pitcher, a good thing to be if you come into the game with runners on.” When he became the team’s manager in 1966, Eddie Stanky threatened to fine Locker $200 for any hit he gave up on a pitch other than the sinker. “Two hundred dollars was a lot of money to me then.” Locker believed his place in the majors was far from secure and he had a family to take care of. And so, though he had misgivings and would come to regret the decision, Locker agreed.

He debuted on a cool, clear afternoon in Baltimore in front of a small house of 4,248 fans. With the White Sox trailing 3-0, Locker entered the game in the seventh inning to face the bottom of the Orioles’ lineup. He gave up a single to the first batter, John Orsino, who stole second and then scored on a single two batters later. Locker got through the first two batters in the eighth, but the heart of the order — Brooks Robinson, Norm Siebern, and Curt Blefary — tagged him for two runs on three straight doubles.

If Locker’s first game was rough, the next couple of weeks were a three-finger prostate exam. He surrendered runs in his first five games. It would be 12 days before he got into a sixth, but the break did him good: he didn’t allow a run in 11 of his next 12 appearances, and he rolled for the rest of the year. Overall, the rookie threw 91⅓ innings and, despite the bad start, he finished 5-2 with a 3.15 ERA.

With all-star Eddie Fisher (2.40 ERA) and future Hall of Famer Hoyt Wilhelm (1.81) in the pen, White Sox manager Al Lopez could shield Locker by using him in low-pressure situations. Throughout the season, he was rarely used when the White Sox were ahead. From May 19 to July 10, Locker pitched 20 times; he entered with a lead only once. It wasn’t glamorous work but it wasn’t grunt work either. “It was Locker,” Fisher said, “who went in to pitch the middle innings and keep the Sox in the game,”4 a role that would come to define Locker’s career. Led by great pitching — the bullpen’s 2.54 ERA was the best in the majors — and great defense, Chicago won 95 games in 1965, but the offense couldn’t keep up. The White Sox finished second, seven games behind the Minnesota Twins.

Overwhelmed by poor mental and physical health, Lopez didn’t return the following year. He handed the team to Eddie Stanky. Compared with Lopez, Stanky wasn’t known to be adroit with pitchers. The transition, though, didn’t hurt the staff. The White Sox again had the majors’ best ERA. The transition didn’t hurt Locker, either. No longer an apprentice, he often got the ball with the game at risk. In late May Fisher told sportswriter Jerome Holtzman that Locker was the best reliever on the team. Despite pitching the last two months with a sore elbow, he dropped his ERA from 3.15 to 2.46. In 95 innings he struck out 70 and gave up only ten unintentional walks. He finished 35 games, up from 14 the year before. He saved two games in 1965, 12 in 1966. The White Sox had great pitching and defense, but a constipated offense kept them out of the World Series once more. They finished fourth, 15 games behind the first-place Orioles.

Chicago finished in fourth again in 1967, held back again by its inept offense. For the third straight year the bullpen had the majors’ best ERA. Locker had a breakout season. He didn’t allow a run in 12 of his first 13 games. His ERA by month was 0.77, 2.35, 2.66, 2.92, 1.63, 1.80, and 0.00. He led AL relievers with 77 games and 124⅔ innings and had the most saves (20) and lowest ERA (2.09) of his career. He ended the season with five straight scoreless appearances.

Every year, scar tissue accumulated in Locker’s pitching arm. Every spring, he spent the first few weeks of camp loosening it. In 1968 the tissue proved more stubborn than usual. He started the season with a sore elbow, and it showed. Batters hit .318/.391/.515 against him through the end of May. The pain began to subside, and Locker’s performance improved to .257/.333/.314 for June. In July Lopez returned as manager and soon after the reunion Locker went 20 straight games without allowing a run. From June through the end of the year he held hitters to .213/.268/.270, and his second-half ERA of 1.38 was the best half-season ERA of his career. Locker’s great second half and another league-leading year for the bullpen couldn’t save the White Sox from their first losing campaign in 18 years, however. They fell to ninth place, 36 games off the league lead.

In 1968 Locker continued to pitch well even as the team around him fell apart, but things were different in 1969. As the White Sox got off to a tepid start, Locker took several beatings. On April 3 the Seattle Pilots pelted him for five hits and four runs in less than an inning. At the end of May the Yankees got to him for four runs in just 1⅓ innings. A bad outing on the first of June swelled Locker’s ERA to 7.23. He remembered that stretch as “the worst 45 days of my career.” Locker’s problem wasn’t physical or mental. It was mechanical. “I lost the sinker,” he recalled. The White Sox grew impatient and on June 8 sent Locker to Seattle, where he joined Jim Bouton and Mike Marshall in the notorious Ball Four bullpen.

Widely regarded as an offbeat, independent thinker, Locker immediately bonded with Bouton and Marshall. “Marshall was a genius,” he said, “especially about pitching. And Bouton” — Locker had no idea a book was in the works — “was scribbling stuff down in his notebook all the time.” Locker had been known to teammates as Wall or Foot. To Bouton he was Snot (a snot locker, explained Bouton, is a nose.5) They worked out together in the outfield before games, Bouton developing his knuckler; Marshall, his screwball; Locker, his sinker. They did more than toss baseballs back and forth. They pitched an eight-pound shot to each other. “People thought we were crazy, but it didn’t hurt our arms. In fact, I think it strengthened all three. I think it might have had something to do with the success I had with my sinker that year.” In addition to throwing an eight-pound ball, Locker did lots of finger exercises. “I had stiff, terrible hands and I needed strength and as much flexibility as I could get.”

Within days of the trade to Seattle, the sinker came back. It returned a bit too exuberantly at first — in his second game for the Pilots, against the White Sox no less, he faced three batters and walked them all — but he quickly tamed the pitch, and over the next two weeks shrank his ERA from 7.12 to 4.09. Before the trade, his ERA was 6.55. Afterward, it was 2.18. Before the trade Locker had fewer innings pitched (22) than hits allowed (26). He had already given up six home runs. After the trade he allowed 69 hits and three homers in 78⅓ innings. It was some of the best work of his career.

For the Pilots, though, the year was a dud. Managed by Joe Schultz, they went just 42-70 after acquiring Locker, and finished in last place. Players loved Schultz but he wasn’t much of a tactician — a manager more inclined to worry about the color of a player’s sweatshirt than what pitch he was working on.6 Schultz’s haphazard management of the Pilots’ bullpen got extensive treatment in Ball Four. Locker, a former military officer, hated the lack of defined roles in a bullpen. Under Schultz and every manager except Dick Williams, Locker never knew what his job was from one inning to the next. “In those days,” he said, “the closer was the only defined role. Other jobs weren’t defined.” Even Al Lopez didn’t tell the relievers, other than his closer, how he planned to use them. “Lopez was very good at handling pitchers but nobody knew what he was thinking. Sometimes I’d warm up in the second inning, then sit, then be called on late in the game. For a reliever there’s nothing worse than spending the whole game on pins and needles with no idea whether you could be called on in the second inning or the ninth.”

The Seattle franchise was moved to Milwaukee for 1970 and installed Dave Bristol as manager. “He didn’t use me as he should have. I don’t know why,” Locker said. “With Seattle the year before, I was throwing as well as I ever had.” And Locker started the year well — six games, no runs — but by the end of April he had allowed 19 baserunners in 10⅓ innings and an OPS (slugging average against plus total bases) of .873. He found himself working the back end of blowouts. By mid-June Locker had appeared in 28 games. The Brewers won five. At 18-41 and 20½ games out of first, the season was already a lost cause. And then, for reasons that remain unclear, Milwaukee sold Locker to Oakland for an undisclosed, and presumably small, amount of cash. From a distance it’s hard to imagine what was in it for Milwaukee. For Oakland, it was a matter of keeping an enemy close. In the previous three seasons, Locker had pitched 27 innings against the A’s and held them to 12 hits and one home run, while striking out 20 and posting a 1.37 ERA.

When Locker arrived in Oakland he was in third place instead of last, six games out of first instead of 20. With Mudcat Grant as the new closer, Oakland’s mediocre bullpen had become one of the league’s strongest. As Locker saw it, the A’s bullpen in the early ’70s was the key to their success. “We always had three or four closers on that team,” Locker said. “That’s why we were so good, not because we had guys who could hit the cover off the ball. We were always in the game.”

The Brewers, like the White Sox, gave up on Locker too soon. With Milwaukee he allowed 37 hits in 31⅔ innings; with Oakland, 49 in 56⅓. He gave Bristol an ERA of 3.41; Dick Williams, 2.88. The A’s finished second but were on the verge of becoming a dynasty.

When the 1971 season began, Williams expected Locker to be the right-handed closer. It would be the first time he had a clearly defined role. On April 27 Locker entered a game in the eighth inning with the A’s trailing 3-2. He put six runners on base that inning (two of them by intentional walks as Williams tried to set up a double play). Three runs scored, pushing his ERA up to 4.63.

Williams decided to give Rollie Fingers a chance to take Locker’s place. Fingers had been with the A’s for a while but mostly as a starter. “He had good stuff,” said Locker, “but knowing he had to pitch every third day or so, he had problems with nerves.” Fingers, who according to Williams “was the clubhouse patsy and the guy tricked into giving his money away or putting on the wrong uniform,” got a chance to close.7

“Rollie went to the bullpen because I wasn’t doing so well,” Locker said. Fingers moved to the pen for good and took over as closer. Locker didn’t have a problem with it. “Rollie had great confidence out of the bullpen. He went right at it. He was awesome.”

Locker lost his job as closer, but he finally knew what his role was every day. When the A’s were down by one or two runs, Locker’s assignment was to make sure things didn’t get any worse. “My job,” he said, “was to stop the other team’s rally and keep us in the game.” Supported by a boisterous offense and great defense, Locker finished the year 7-2. Other than that, Locker was the same in 1971 as he had been in 1970. His walk rate came down a little (from 3.0 per nine innings to 2.4) but his strikeout rate, home run rate, ERA, and WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) hardly changed at all.

With Locker and Darold Knowles handling setup duty from the right and left sides, and Fingers reprising his role as closer, Williams expected his bullpen to be unstoppable in 1972. Was the pen as good as the ones Locker was part of in Chicago? “It’s hard to compare our bullpen here with the one in Chicago,” he said. “Over there, we all had trick pitches. Wilhelm and [Wilbur] Wood threw those knucklers, and” — referring to his side-arm delivery — “I come from Port Arthur.”8

The A’s won four out of five to start the season, went 18-3 from May 20 to June 10, and went into July 43-23, four games ahead of the White Sox. Through July and August the A’s hit poorly, pitched well, and essentially played .500 ball. Meanwhile the White Sox steadily gained ground. They began a 26-10 run on July 19 and surpassed Oakland by a half-game on August 27. But within 48 hours the A’s reclaimed the lead and never gave it back.

Between August 6 and September 11, Locker pitched 17 times without allowing a run, the second longest scoreless streak of his career. He finished the year 6-1 with a 2.65 ERA. Overall, his hit, walk, strikeout, and home run ratios were the almost the same as they had been in 1970 and 1971.

From 1970 to 1972, Locker threw 206⅔ regular-season innings for the A’s, with an ERA of 2.79. He allowed four home runs — one every 51 innings — and 37 unintentional walks. He preserved enough winnable games in 1971 and 1972 to go 13-3.

Locker turned that performance upside-down in the playoffs. He pitched in four postseason games in 1971 and ’72. Oakland was in every game when Locker came in, but they went 0-4. Of the 14 batters he faced, 11 were right-handed, an ideal setup for a right-handed specialist, but five of the 11 reached base and three scored. His career playoff ERA was 9.00.

“Williams wasn’t enamored with me,” Locker said of the 1972 postseason. He might have been on borrowed time even before the 1972 playoffs. “Dick was the best manager I ever had,” he said, “but I don’t think he liked me. If you asked him, he would say something not too kind about me, I imagine. I was a free spirit, or whatever you’d call it and Dick just didn’t dig my vibe.”9

Two months after the A’s won the World Series, they flipped the 34-year-old Locker to the Chicago Cubs for coveted prospect Bill North. The A’s were thrilled with the deal but Locker was so upset he threatened to quit. Some in Chicago didn’t like it either. Jerome Holtzman wrote, “It could turn out to be [GM John] Holland’s worst trade since he sent Lou Brock to the Cardinals in 1964.”10

Locker was sullen and apprehensive when he reported for training camp in 1973. “I don’t like the idea of coming here,” he told Holtzman.11 It was his first time in the National League. He didn’t know his teammates and they didn’t know him. Making matters worse, he had a sore arm. “My arm was so weak I couldn’t break a pane of glass.”12

Opening Day cheered him up. On a cool, sunny day at Wrigley Field, the Cubs beat the Montreal Expos 3-2 with a ninth-inning rally. Locker watched the comeback from the bench instead of the bullpen. “I was amazed to hear these guys yelling and cheering,” he said. “And I don’t mean the extra men. I mean stars — guys like Santo and Kessinger and Williams and Hundley and Beckert. They were yelling their heads off.”13

Realizing his fastball wasn’t what it used to be, and discovering that he was in a fastball-hitting league, Locker knew he had to expand his repertoire. At the time, he was infatuated with Jonathan Livingston Seagull, a fable about self-perfection. He turned to Bill Bonham, who owned the team’s best changeup, for help. They worked out together, they roomed together, and before long Locker had his changeup back. “My goal was to throw three consecutive changeups for a strikeout,” he said. “Eventually it worked.” It worked especially well against lefties (.541 OPS in 1973), who had always given Locker more trouble than righties.

Locker carried a 1.96 ERA into June. He pitched with a lead — and under pressure — more than ever. He continued to pitch well and, despite a record of 64-69, the Cubs entered September only 3½ games behind the St, Louis Cardinals for the division lead. With the pennant an arm’s length away, manager Whitey Lockman nearly doubled Locker’s workload down the stretch, using him 17 times in the Cubs’ final 28 games. Locker responded with a 2.61 ERA, five saves, and a 3-1 record, but it wasn’t enough. The Cubs finished in fifth place.

Locker pitched 106 innings in 1973, his most since 1967. He saved 18 games and won ten. He had a 2.54 ERA, even though he worked in a hitter’s park and had the league’s worst defense behind him. In a sense, 1973 was his best year. He contributed more to his team’s wins — measured by Wins Above Replacement and Win Shares — than any other team he had played for.

The 1973 season was Locker’s last good year. Whitey Lockman’s desperate push for the pennant cost Locker his elbow. He missed the entire 1974 season but midsummer surgery had him ready for spring training in 1975. Ever since he arrived at his first training camp wearing a weighted vest, Locker proved himself to be a fitness fanatic. When he was with the A’s, he sprinted against younger players and Charlie Finley’s kids, and he outran them all. As he saw it, fitness was just one more edge he needed to overcome his liabilities. He came to spring training in 1975 feeling stronger than ever. Even the elbow felt good. But a shoulder problem developed before the end of camp. By June 25, when the Cubs released him, Locker had more walks than strikeouts and a 4.96 ERA in 32⅔ innings. He took the flight home from Montreal and never returned to baseball.

Locker returned with Judy to the Bay Area, where they raised three boys and one girl. Having occasionally worked in real estate during his baseball career, he was able to build a second career in real estate and exterior design. After 40 years in the Bay Area, he retired to Montana in the late 2000s, became an inventor, and taught himself to write. He published two books, Cows Vote Too in 2013 and Esteem Yourself the following year. Esteem Yourself, he said, was meant to inspire young people. “If allowed to do what they want, they’re going to do what they want. It’s all what can I do to entertain myself, not what can I do to improve myself. Young people don’t have self-esteem, because they haven’t had to earn it. They haven’t had to do something for someone and feel good about it.” In addition to inventing and writing, Locker collaborated with Jim Bouton to create ThanksMarvin.com, a website in tribute to Marvin Miller.

Throughout his career, Locker played equally well for four organizations, no matter what kind of offense or defense he had around him, regardless of whether he was in a hitter’s or pitcher’s park. Consider this: His ERA was 2.68 for the White Sox, 2.54 for the Pilots and Brewers, 2.79 for the A’s, and (excluding his abortive comeback in 1975) 2.54 for the Cubs. He frequently pitched in pain, but until his final year he never lost significant time to injury. He threw at least 88 innings in seven out of nine seasons between 1965 and 1973. Three organizations gave up on him, and he bounced back each time. Consistency, durability, resiliency — these traits, not just the sinker, made Locker an asset wherever he went. “The reality is that I was never a star, but when I got to the end of a career spent running scared, looking back I had good stats. The reason I was successful is that I avoided slumps. Other than the start of 1969, when I couldn’t find my sinker, I never had a bad year. I never let a bad outing become a bad week, or a bad week become a bad month, or a bad month to become a bad year. I always fought back.”

Last revised: August 28, 2022 (zp)

Notes

1 All quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from interviews with Bob Locker in May 2014.

2 Edgar Munzel, “Rookie Dares to be Different —He Works Out in a Weighted Vest,” The Sporting News, March 20, 1965.

3 Jim Bouton, Ball Four Plus Ball Five: An Update 1970-1980 (New York: Stein and Day, 1980), 211.

3 Bob Locker, telephone interview, May 15, 2014.

4 Jerome Holtzman, “Bob Locker,” The Sporting News, May 28, 1966.

5 Bouton, 210.

6 Bouton, 156.

7 Dick Williams and Bill Plaschke, No More Mr. Nice Guy: A Life in Hardball (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1990), 132.

8 Ron Bergman, “No Wonder A’s Are Tough: Their Bullpen Unbeatable,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1972.

9 Ed and Meat’s Sports on the Street, “My Interview With Bob Locker,” November 17, 2009, sportsonthestreet.blogspot.com/2009/11/my-interview-with-bob-locker.html.

10 Jerome Holtzman, “Cubs Look to Locker to Turn Bullpen Key,” The Sporting News, December 9, 1972.

11 Jerome Holtzman, “Suddenly Locker Likes Cubs —‘No Reason Why We Can’t Win,’” The Sporting News, April 28, 1973.

12 Holtzman, “Suddenly Locker Likes Cubs.”

13 Holtzman, “Suddenly Locker Likes Cubs.”

Full Name

Robert Awtry Locker

Born

March 15, 1938 at George, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.