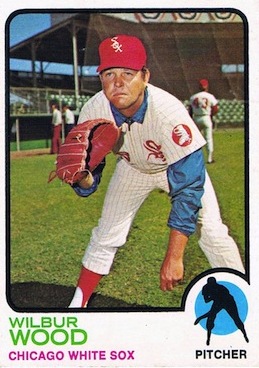

Wilbur Wood

Arguably the best left-handed knuckleball pitcher in major-league history, Wilbur Wood’s 19-year professional baseball career may be best described as a case study in patience, resiliency, and determination. Signing as a highly touted fastball-curveball pitching prospect in 1960, Wood failed five times (three times with the Boston Red Sox and twice with the Pittsburgh Pirates) to land a spot in the big leagues.

Arguably the best left-handed knuckleball pitcher in major-league history, Wilbur Wood’s 19-year professional baseball career may be best described as a case study in patience, resiliency, and determination. Signing as a highly touted fastball-curveball pitching prospect in 1960, Wood failed five times (three times with the Boston Red Sox and twice with the Pittsburgh Pirates) to land a spot in the big leagues.

Given his second outright option, in 1966, he toiled in the minor leagues and was purchased by the Chicago White Sox. Under the tutelage of future Hall of Famer Hoyt Wilhelm, Wood transformed himself into knuckleballer and enjoyed unimaginable success. After a three-year period (1968-1970) as baseball’s most durable reliever, Wood entered the starting rotation and racked up statistics reminiscent of Deadball Era pitchers during a four-year period from 1971 to 1974 winning a big-league best 90 games and averaging almost 350 innings per year.

Wilbur Forrester Wood was born on October 22, 1941 in Cambridge, Massachusetts to Wilbur Sr. and Svea (nee Swenson) Wood. Growing up in Belmont, on the northwest side of greater Boston in Middlesex County, Wilbur and his younger brother Jimmy played sports year-round –from football to hockey to baseball as the seasons changed. Employed in the wholesale food business, Wilbur Sr., was a former semipro shortstop and taught the left-handed Wilbur to throw a knuckleball when he was in junior high, though it wasn’t until years later that the pitch became his son’s trademark. At Belmont High School, Wilbur was an all-around athlete, leading his football team as a quarterback, anchoring the hockey team as a defenseman, and starring as a pitcher on the baseball team. A self-described fastball-curveball pitcher, Wilbur compiled a 24-2 record, including four no-hitters, in his high-school career, and led his team to the state championship as a junior in 1959. He also won 42 games for coach Joe Dwyer while playing for Post 99 in the local American Legion league.

“There were about 50 colleges after Wilbur for a variety of sports,” recalled Bill Stone, Wilbur’s high-school baseball coach.1 Wood wanted to play professional baseball and drew interest from a number of teams, including the Cardinals, the hometown Red Sox, and Braves who flew him to Milwaukee for a tryout. “He was a chubby little guy who didn’t throw very hard. I watched him throw batting practice (and) couldn’t get very excited,” said Roland Hemond, the Braves’ farm director at the time and later Wood’s boss as general manager of the White Sox.2 “I wanted to play for the Red Sox, but at that point I wanted the club that offered me the most amount of bonus money,” Wood said candidly.3 With Ted Williams’ impending retirement, the Red Sox were on a downward spiral at the time, in search for a new identity. Hoping to capitalize on the media coverage of the “local boy makes good story,” team owner Tom Yawkey authorized scout Neil Mahoney to offer Wood a bonus variously reported from $25,000 to $50,000. Wood signed in 1960 shortly before graduating from high school.

With great local media coverage, the 18-year-old Wood reported to the Class D Waterloo (Iowa) Hawks in the Midwestern League. After just four appearances he was reassigned to the Raleigh (North Carolina) Capitals in the Class B Carolina League where he posted a 3-5 record and 3.84 ERA in 77⅓ innings. Added to the Red Sox’ 40-man roster at the conclusion of the season, Wood participated in his first big-league spring training, in Scottsdale, Arizona, the following spring. After Wood struck out the side against the Giants in his debut, the Boston Globe prematurely predicted immediate “spectacular success” for the prospect.4 Optioned to the Winston-Salem (North Carolina) Red Sox in the Class B Carolina League at the end of spring training in 1961, Wood won eight of 13 decisions before being promoted to the parent club in mid-June to spark fan interest for a floundering team struggling at the gate (drawing just over 10,000 a game). Debuting in Fenway Park on June 30, Wood pitched the final four frames in a 10-2 loss to the Cleveland Indians, surrendering three hits and two runs while striking out three. Wood appeared in five more games as a reliever before being optioned to the Johnstown (Pennsylvania) Red Sox in the Class A Eastern League where he struggled winning just three of ten decisions.

After a successful season with the York (Pennsylvania) White Roses in the single-A Eastern League in 1962 (15-11 and a 2.84 ERA in a league-high 219 innings), Wood arrived at his third consecutive spring training in 1963 with a chance to make the team. Among the last cut, he was optioned to the Seattle Rainiers, where he was the hottest pitcher in the Pacific Coast League, winning five of seven decisions and posting a 1.12 ERA, thus earning his second midseason call-up to the Red Sox. “My bread and butter pitch is my curve,” said Wood who explained that he occasionally used a knuckler to upset and trick a batter.5 However, major-league batters were not tricked by his curve and fastball, and pummeled him for 39 hits in just 28 innings in his first six starts. With a 0-4 record and 5.49 ERA, Wood was demoted to the bullpen where he posted a 2.45 ERA over 36⅔ innings during the remainder of the season. “The little sonofagun just couldn’t throw hard enough,” said Boston manager Johnny Pesky. “But he wanted to pitch and tried his hardest.”6

Though winless thus far in his major-league career, Wood scored a big win on November 6, 1963 when he married high-school sweetheart Sandra Malcolm. They made their home in the Boston area, where Wood worked in the food industry during the offseason. They had three children (Wendy, Derron, and Christen).

Down to his last option, 1964 was a make-or-break year for Wood. “This ballpark (Fenway) hurts this lefthander,” said pitching coach Bob Turley ominously.7 Clobbered for 11 runs in just 5⅔ innings in four relief appearances, Wood’s dream to play for his hometown team came to a dramatic close when he was given his outright release to the Seattle Rainiers in mid-May. Astonishingly, he turned his season around by going 15-8 in the P.C.L. and was named to the all-star team. On September 6, the Pittsburgh Pirates purchased his contract and promoted him to the parent club. Still in search of his first big-league win after six career losses, Wood concluded the season with a heartbreaking loss to the Milwaukee Braves on October 2 by walking Woody Woodward with bases full with two out in the tenth inning to lose a complete game, 3-2.

Wood was buried deep in Pirates’ bullpen for the entire 1965 season. Soft-spoken and amiable, Wood did not get along with brash manager, Harry “the Hat” Walker, who used Wood almost exclusively in mop-up situations (the Bucs lost in 30 of Wood’s 34 appearances). Even though Wood pitched respectably (1-1 and a 3.16 ERA in 51⅓ innings) the previous season, he was cut mid-way through spring training in 1966 and was released outright to the Columbus Jets of the International League. “In the major leagues, my fast ball just wasn’t that good,” said Wood years later. “So naturally I threw curve after curve and they knew what was coming.”8 Having failed five times to make it in the major leagues, Wood was at a crossroads in his career. “He was very discouraged,” said wife Sandy after Wood was cut. “I think he might have gone into the plumbing business with my father.”9

Just 24 years old, but in his sixth year of professional baseball, Wood rallied with the hitherto best year of his career at arguably the most crucial point. Named the I.L.’s most outstanding pitcher, Wood posted a 14-8 record and led the league in innings (224), complete games (15), shutouts (8), and ERA (2.41 among pitchers with at least 20 starts). Based on team scout George Maltzberger’s glowing report, general manager Ed Short of the pitching-rich White Sox, fresh off a league-best 2.68 team ERA, acquired Wood at the end of the season (and later sent the Pirates Juan Pizarro to complete the transaction).

Wood arrived at the White Sox spring training in Sarasota, Florida, with his career in jeopardy. “[Manager] Stanky told me that there was no starting job for me and also I couldn’t be a short relief man,” said Wood.10 Despite the news, he was not discouraged. “I knew had to make up my mind one way or the other. It was getting to the point in my career where I either make it or go home.”11 But Wood had a stroke of luck. He landed on the one team with perhaps the only person who could help him: 44-year-old knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm.

Wilhelm and Wood began throwing the knuckler to each other at spring training, careful not to injure one another. Finally, Wilhelm convinced Wood, “You either throw the knuckleball all of the time or not at all. It’s not an extra pitch.”12 Though he had thrown the knuckler for close to 20 years, Wood lacked confidence in it and couldn’t control it well. The master-teacher Wilhelm taught Wood the intricacies and mysteries of the dastardly pitch. First, Wilhelm helped with his delivery. “I had a tendency to drop down with my arm when I threw the knuckler. Hoyt has me throwing it strictly overhand. [The knuckleball] breaks down more consistently,” Wood explained.13 Wood had already mastered the grip (with the tips of his fingers), so Wilhelm helped refine the follow-throw of his wrist. “[Wilhelm] has me throwing the knuckler more with a stiff wrist and with the hand up. If you twist your wrist either way, the ball will rotate and you won’t get a good break.”14

Wood’s transformation into a knuckleball pitcher paid immediate dividends. In 26 relief appearances in the first half of the season, Wood posted a microscopic 1.51 ERA. With starters Jim O’Toole injured and John Buzhardt pitching inconsistently, Wood was given a spot start in July and held the Kansas City Athletics to seven hits over 8⅓ innings to win his first game as a starter. Wood parlayed his success into seven additional starts in the ensuing five weeks and won four of them. Working out of the bullpen for the rest of the season, Wood was an integral contributor during the White Sox pennant race, pitching 11 times in the fateful last month of the season. Finishing with a 2.45 ERA over 51 appearances and 95⅓ innings, Wood commented, “I probably wouldn’t have paid as much attention to the knuckler if I thought I might wind up as a starter.”15

Firmly established as one of the team’s most important relievers, Wood began camp in 1968 with a sense of confidence and relaxation he never had before. He continued to work with Wilhelm to refine his knuckleball and make adjustments when the ball was flat or hung. Wood credited pitching coach Marv Grissom for helping him alter his wind-up. “I used a full wind-up at the start of [the 1967] season. Then in midseason, I went to a half-windup. In spring training this year,” Wood said, “Grissom talked me into not using my wind-up at all.”16 Getting rid of the windup had two immensely important effects: it made his occasional fastball and curve more effective because they were even less anticipated without a wind-up. Secondly, it gave Wood one of the best, if not the best pickoff move to first base in all of baseball. Wood’s confidence in his knuckler was boosted by his trust in his catchers, Duane Josephson and Jerry McNertney whose experience catching the pitch resulted in few passed balls.

Over the course of the next three seasons (1968-70), Wood established himself as the most durable and one of the best relievers in baseball on dismal White Sox teams that were collectively 104 games under .500. During this era, relievers’ roles were not as defined as they are in today’s game. Teams often had multiple “closers” (though the word was not commonplace at the time) and relievers were expected to be able to pitch multiple innings and serve as general “firemen,” ready to quell any rally. When Bob Locker, who often finished games, experienced problems in May 1968, manager Stanky replaced him with Wood, thereby giving him even more opportunities to pitch. Wood responded by pitching in a major-league record 88 games (broken the followed year when Wayne Granger pitched in 90 for the Reds). He posted a microscopic 1.87 ERA in 159 innings and his 13 wins led the team. In an era before the save was an official statistic, Wood paced the team with 16 (Wilhelm had 12 and Locker 10). White Sox beat reporter, Jerome Holtzman called Wood’s rise from relative obscurity to stardom “sensational” and The Sporting News named him the A.L. Fireman of the Year.17 “He’s an amazing pitcher,” said Stanky, who was fired in midseason.18

Wood’s success and rubber-arm gave rise to the discussion that he might become the first hurler to pitch in 100 games in a season. Though he didn’t approach that prediction, his 1969 and 1970 seasons are remarkable similar. He again led the American League in appearances in both seasons (76 and 77) giving him a total of 241 in three years. He logged 119⅔ and 121⅔ innings while posting earned run averages of 3.01 and 2.81. “I owe Hoyt an awful lot,” said the ever-humble Wood who was always ready to give others credit for his success. “I wouldn’t be in the major leagues, if I hadn’t been for Hoyt and the help he gave me with the knuckleball.”19

Able to stay mentally focused despite playing for weak-hitting and poor-pitching teams, Wood often pitched when the game was tied or with the White Sox behind; consequently, his record during these years (13-12, 10-11, and 9-13) may not seem spectacular. He readily and often admitted that the knuckleball was less physically stressful on his arm, but noted it didn’t make pitching easy. Wood had an unflappable and serious mound presence, and was not easily distracted. “I’m nervous every time I go out there,” Wood said. “It’s a thrill – and a challenge. If you are not exciting when you come in, you’re lost. But I don’t lose my concentration because of a hit or a wild pitch.”20 This attitude was especially helpful in 1970 when Chicago lost a franchise-record 106 games. When Chuck Tanner took over for the last 16 games of that season, Wood’s career was changed forever.

The White Sox had a dismal staff in 1970 and ranked last in the A.L. with a 4.54 team ERA; Tommy John (12-17, 3.27), Gerry Janeski (10-17, 4.77), and Joe Horlen (6-16, 4.86) were the only pitchers to make at least 20 starts. Tanner hired the outspoken, yet innovative Johnny Sain as pitching coach. Sain had worked wonders with several staffs in the 1960s (Yankees, Twins, and Tigers) but his unorthodox methods frustrated managers and team brass. During the offseason, Tanner announced his plan to make the 29-year-old Wood a starting pitcher even though success in the rotation had eluded him thus far in his career. GM Roland Hemond had other plans for Wood. He wanted to rebuild the White Sox with youth. Even before camp broke, he offered Wood to the California Angels in a package deal to acquire young pitchers Dave LaRoche and Lloyd Allen. “They turned us down,” said Hemond. “If Wilbur had gone there, or anywhere else, he might not have ever become a starting pitcher.”21 When Horlen went down with a broken leg just days before the season opened, Wood’s fate as a starter was sealed.

Pure knuckleball starting pitchers are a rare breed in the major leagues and successful ones are even rarer. In 2012, the Mets’ R.A. Dickey became the first one ever to win a Cy Young Award. Wood joined the Braves’ Phil Niekro and his younger brother Joe Niekro as the majors’ only knuckleball starters (the Dodgers’ Charlie Hough was pitching from the bullpen at the time). After a slow April (no decisions in three starts), Wood got on track in May, winning three times, including his first career shutout on May 22 when he blanked the Angels on six hits, winning 13-0. Whereas most staffs at the time consisted of four-man rotations with pitchers pitching on three days rest, Sain approached Tanner to discuss the possibility of Wood pitching regularly on short rest. Tanner agreed and so did Wood. On June 30, he pitched a complete game to defeat the Brewers, 8-3, on two days rest. With shutouts in two of in next three starts, Wood improved his record to 9-5 and lowered his ERA to 1.69 before the All-Star break. Sain was not surprised by Wood’s success. “I guess they always said, ‘Poor Wilbur, he just doesn’t have enough natural ability to pitch in the big leagues,’” said Sain. “What they call natural ability is standing six-four and being able to throw a ball 100 miles per hour. Well, it turns out that he has as much God-given ability as any man I’ve ever met. He can throw the knuckleball [and] it requires [a] natural feel.”22

Relishing in his new role as a modern pitching ironman, Wood enjoyed phenomenal success with his new routine of pitching twice per week (alternating between two- and three-days’ rest). With nine starts in August and September, Wood concluded the season with complete games in seven of his last eight starts, including three shutouts. In his last start of the season, he struck out a career-high 10 (achieved four times) to defeat the Brewers, 2-1, for his 22nd victory of the season. In 23 second-half starts, he won 13 of 21 decisions, logged 185 innings, including 15 complete games and four shutouts. Even more impressive were his results on two days rest for the season: 11 complete games in 15 starts and an 8-4 record with a 2.10 ERA. “I feel no difference, physically or mentally, between two and three days of rest,” said Wood about his workload. “Everybody thinks I should be more tired, but I am not.”23

Wood finished second in the AL in innings (334), ERA (1.91), shutouts (7), third in wins (22), and struck out a career-high 210. Great numbers, to be sure, but how good? Advanced sabrmetric statistical analysis may help. Based on Wood’s WAR24 for pitchers (11.5), his season was one of the best in major-league history after 1920, exceeded only by Roger Clemens (11.6 in 1997), Steve Carlton (11.7 in 1972), and Dwight Gooden (11.9 in 1985).

Wood’s success brought him national attention as a throw-back to another era. Described as “affable, genuine and popular,” Wood certainly did not cut an imposing figure on the mound with his 6’0” 180-frame.25 Media reports often described him portly, roly-poly, round, or rotund; award-winning writer Peter Gammons thought Wood could pass as a plumber or even a beer-taster in a brewery.26 White Sox beat reporter Edgar Munzel wrote in The Sporting News, “There isn’t anyone in the major leagues . . . who looks less like a ballplayer. He’s a chubby, pot-bellied guy with thinning blond hair, blue eyes, and a pleasant round face.”27 For the remainder of his career, Wood was dogged by these unflattering physical descriptions, along with suggestions that throwing a knuckleball was somehow less demanding than a fastball, all of which gave the impression that Wood’s success was the result of a fluke pitch and that he didn’t need to work hard or be fit to pitch. Scoffing at such notions, manager Tanner once offered a different perspective: “He’s a stubborn competitor and has ability and courage to go with it.”28 Always quick to point out that great pitching is even more difficult than hitting, Sain suggested that Wood’s success rested as much on his mental preparation as on his physical abilities, “Wilbur has tremendous poise. He has the perfect temperament [and] never gets rattled.”29 With his strong Boston accent, Wood was a player’s player who liked to joke with teammates.

In a four-year span from 1971 to 1974, Wood pitched more than anyone since the Deadball Era, and his statistics appear as though from a video-game. He won at least 20 games each season, leading the A.L. with 24 wins in 1972 and 1973, and his 90 wins were the most in baseball, two more than Catfish Hunter. He logged 1,390 innings, averaging 348 per year. In 1972, a season shortened by the players’ strike (the White Sox played 154 games), Wood logged 376⅔ innings, ⅔-inning more than Mickey Lolich the previous season, and the most in the AL since Chicago’s Ed Walsh’s 393 in 1912; and he started 49 times, tying Walsh’s mark in 1908, and the most in the A.L. since Jack Chesbro’s 51 for the Yankees in 1904. With the ability to start so frequently, sportswriters predicted that Wood would win 30 games.

Despite his accomplishments, Wood is typically overlooked as one of the best pitchers from his era, in favor of Jim Palmer, Tom Seaver, Nolan Ryan, Steve Carlton, Catfish Hunter, and Gaylord Perry, to name just six. Wood never had his moments on the big stage. He was named to the A.L. All-Star team three times (1971, 1972, and 1974), but pitched only once, a two-inning outing surrendering two hits and one run in 1972. The White Sox’ record during those years (just one winning season) contributes to the lack of attention, as does Wood’s relatively short career as a starter (and thus fewer career wins) in comparison to the afore mentioned. Wood also lost a major-league high 69 times during this stretch and in 1973 became the first pitcher since Walter Johnson in 1916 to win and lose at least 20 games in one season.

Wood’s knuckleball was slower (and thus easier to catch) than Phil Niekro’s or Hoyt Wilhelm’s. Wood’s success depended on his delivery. “You must push it,” he said, “but then you must break your wrist in a downward motion. When you throw a knuckleball properly, it makes one and one-half revolutions when traveling to the plate.”30 He held the ball with his thumb, ring finger and pinky in the same position as he did with a fastball, but his fingers did not touch the seams. If the ball rotated more than planned, the knuckler appeared as an easy-to-hit hanging curve. The pitch bewildered and aggravated batters. “I see the ball floating up and then I swing,” said the A’s Gene Tenace. “I get a feeling that the bat has made a ripple in the air and has caused the ball to wriggle.”31 Paul Blair was impressed with Wood’s uncanny control, “What makes [Wood] more effective is that he throws it over for strikes. It never goes the same way, but it is always in the strike zone.”32

Wood’s durability compensated for his lack of overpowering pitches. Once Wood demonstrated he could pitch effectively on two days’ rest the media wondered when Wood would pitch in both games of a doubleheader which had not been done since Don Newcombe shut out the Phillies in game one and then hurled another seven innings in game two, giving up just two runs in a no-decision, on September 6, 1950. Wood came close on May 28, 1973 when he pitched the final five innings of a suspended game, yielding two hits and one run (none earned) to defeat the Cleveland Indians in Comiskey Park. He then shut out the Indians on four hits the same day. Wood got his unexpected chance on July 20, 1973 at Yankee Stadium. He was chased in the first game without registering an out, clobbered for four hits and six runs. Tanner gave him a shot in the second game, but Wood pitched dismally, surrendering five hits and seven runs in 4⅓ innings and was tagged for the loss in both games.

Without a no-hitter or one-hitter in his career, Wood tossed three career two-hitters. Coincidentally, two of them were 11-inning efforts. The latter, a 1-0 victory over the Tigers on May 7, 1974 was arguably Wood’s best performance in his career; it was also one three games that season (and five in his career) in which he pitched at least ten innings, including a career-high 13-inning, complete-game loss to the Royals on May 25. Gradually losing some effectiveness by 1975, Wood won 16 and lost a league-high 20, while his ERA rose to 4.11 in 291⅓ innings; however, he led the A.L. in games started for the fourth consecutive season and had moments of baffling dominance. His last two-hitter (a shutout against the Tigers) was bookended by a three-hit shutout and a four-hit complete game victory during a three-start stretch in July.

Bill Veeck’s purchase of the White Sox in December of 1975 inaugurated a new era for the team. Wood blanked the Royals on six hits to win the Season Opener and started six of the team’s first 14 games. In his seventh start, on May 9, Wood’s career took a sudden and expected turn. With two outs in the sixth inning, the Tigers’ Ron LeFlore hit a bullet back to the mound and shattered Wood’s left knee cap. “I never saw the ball,” Wood said later.33 The hit ended Wood’s season (he had won four of seven decisions and posted a stellar 2.24 ERA), and he was never the same thereafter. Two years later he was out of baseball.

The final two years of Wood’s career were as disappointing as they were frustrating. Wood was made available in the AL expansion draft in 1976, but with his recovery uncertain and high salary (in excess of $100,000), he was not chosen. The perpetually cash-strapped Veeck tried to deal him, but there were no takers. As fate would have it, the 1977 White Sox team, aptly named the “Southside Hitmen” for their home-run hitting prowess, was the best team Wood ever played on; unfortunately, he was a shell of his former self, winning just seven times in 15 decisions, while posting a 4.99 ERA in 122⅔ innings. “I was a little gun-shy,” Wood said about his return. “I didn’t want the ball coming back over the middle again.”34

Wood returned in 1978, but with a 10-10 record and 5.20 ERA in 168 innings, was put on waivers in late August. Claimed by the Pirates and Brewers, Wood decided to remain with the White Sox, opting for free agency at the conclusion of the season. Unsigned in the offseason and not drafted in the supplemental draft for reentering free agents, in February 1979, Wood’s career came to an unglamorous close with ill feelings toward management. “I just couldn’t do what I could do before I got hurt. That took the fun out of it.”35 Wood finished his 17-year major-league career with a 164-156 record and a 3.24 ERA 2,684 innings. He also won 64 games in his six years in the minor leagues.

Wood retired from the game and returned to his home town of Belmont where he purchased a fish market. In the late 1980s, he became an account manager for a pharmaceutical company and has worked in that field ever since. He remarried in 1991, and he and his wife, Janet, reside in the Boston area. An avid fisherman, accomplished cook, and gardener, Wood still enjoys baseball, though has mentioned in interviews that he hasn’t followed it closely since he retired. Wood’s career, from local phenom and five-time bust with the Red Sox and Pirates, to star reliever then starting pitcher for the White Sox, underscores his passion for the game and willingness to change and learn. But it is also a reminder that players sometimes need a little luck, fate if you will, to be in the right place at the right time to succeed.

Last revised: December 19, 2013

Sources

Wilbur Wood player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

BaseballReference.com

New York Times

Retrosheet.com

The Sporting News

Notes

1 D. Leo Monahan, “Baseball Wood’s Childhood Ambition.” [No publication, no date]. Wilbur Wood player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

2 Peter Gammons, “The Unlikely Wilbur Wood,” Boston Globe, July 22, 1973, 6.

3 Rich Thompson, “Time was right for Wood,” Boston Herald, May 28, 1989, B23.

4 Peter Gammons, 7.

5 The Sporting News, June 1, 1963, 33.

6 Peter Gammons, 7.

7 The Sporting News, December 21, 1963, 15.

8 Jack Sheehan, Director of Publicity, Chicago White Sox Press Release. [no date]. Wilbur Wood player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

9 Tim Horgan. [no publication, no date].Wilbur Wood player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

10 Jack Sheehan, Director of Publicity, Chicago White Sox Press Release. [no date]. Wilbur Wood player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

11 Richard Thompson, Boston Herald, May 28, 1989, B23.

12 Ibid.

13 The Sporting News, May 6, 1967, 7.

14 Ibid.

15 The Sporting News, August 5, 1967, 8.

16 The Sporting News, July 13, 1968, 19.

17 Ibid.

18 The Sporting News, July 13, 1968, 19.

19 Jack Sheehan, Director of Publicity, Chicago White Sox Press Release. [no date]. Wilbur Wood player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

20 The Sporting News, May 16, 1970, 22.

21 Gammons, 12

22 Gammons, 10.

23 The Sporting News, October 2, 1971.

24 Wins Above Replacement, an advanced sabrmetric statistic, presents, in the form of a single number, the number of wins the player added to the team above what a replacement player (e.g., triple-A player) would add.

25 Elizabeth Karagianis, “Former baseball knuckler Wilbur Wood says he’s happy pitching fish and chips,” Boston Globe, April 27, 1985. [no page]. Wilbur Wood player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

26 Gammons

27 The Sporting News, June 2, 1973, 3.

28 The Sporting News, August 5, 1972, 10.

29 The Sporting News, May 13, 1972 9.

30 Jack Sheehan, Director of Publicity, Chicago White Sox Press Release. [no date]. Wilbur Wood player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

31 Sports Illustrated, June 4, 1973, 4.

32 Ibid.

33 The Sporting News, May 22, 1976, 20.

34 Tim Alan Smith, “Wilbur Wood, Knuckleballer,” Sports Illustrated, December 24, 2001. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1024587/index.htm

35 Elizabeth Karagianis, Boston Globe, April 27, 1985. [no page]. Wilbur Wood player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Full Name

Wilbur Forrester Wood

Born

October 22, 1941 at Cambridge, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.