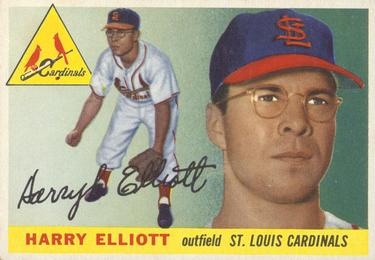

Harry Elliott

Many famous major-league players had their careers interrupted by military service in World War II, and we wonder what records men like Ted Williams, Bob Feller, Joe DiMaggio, Phil Rizzuto, Pee Wee Reese, Hank Greenberg, and others might have achieved if it hadn’t been for those lost years. Furthermore, a large group of younger men had the start of their careers postponed because of the war.

Many famous major-league players had their careers interrupted by military service in World War II, and we wonder what records men like Ted Williams, Bob Feller, Joe DiMaggio, Phil Rizzuto, Pee Wee Reese, Hank Greenberg, and others might have achieved if it hadn’t been for those lost years. Furthermore, a large group of younger men had the start of their careers postponed because of the war.

Harry Elliott is one of the latter. He graduated high school in 1942, but did not begin his pro baseball career until 1951. When he made his major league debut with the St. Louis Cardinals on August 1, 1953, he was five months shy of his 30th birthday. It is tempting to wonder what his career might have looked like if he had been able to start pro ball right out of high school.

Harry was born on December 30, 1923, in San Francisco, California to Harry Elliott Sr. and Stella Scott. According to Harry, his father and mother divorced when he was about two years old. Harry Sr. was a musician and carpenter, but Harry never really knew his father. He thought his biological father died sometime in the 1940s.1 However, Stella is listed as a widow in the 1930 United States Federal Census. Stella remarried to George Metcalf and moved to rural Winsted Township in Minnesota sometime after April 1935.2 George’s occupation in the 1940 census was listed as manager at a “Dried Milk Factory,” probably at Pure Milk Products in Winsted.

Harry attended school in Lester Prairie, Minnesota, through his sophomore year, and graduated high school in a class of 31 at Watertown in May 1942. (See the table at the end of this story for context on the population of Minnesota’s small towns.) He was an all-around athlete, starring in football, basketball, and baseball. He played third base and batted third or fourth for the Winsted town team in 1941.

Harry also played piano and formed a band, “The Royal Windjammers,” with a teacher and two other students. They played at the Platwood Club, a ballroom in nearby Norwood, and for other local occasions. Harry was a confident young man. The Winsted Class of 1942 “Senior Poem” included the line, “And what Harry can do is just about anything.”3 His entry in the “Senior Will” read, “Harry Elliott wills his big head to Robert Pierson.”4

Elliott was not making big plans after graduation. His stepfather and mother were planning to move to Shiocton, Wisconsin, but he wanted to stay in Minnesota. He moved to nearby Watertown to play with their town team, registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, and figured he would be in military service for at least the next few years. He was restless, though; answering an ad in Downbeat magazine for a pianist, he found himself playing with a quartet in North Carolina. The group eventually broke up. Harry figured two of the men were draft dodgers, and the other had had a drug rehab relapse.5

He hitchhiked across the country to live with his maternal grandmother in San Francisco. While there he enlisted in the Navy, and became an F6 Hellcat pilot, serving from 1943–45. He was stationed in California, Corpus Christi, and a couple other stateside places, but did not see combat service, and was discharged from Great Lakes Naval Station in Chicago. Elliott said he didn’t have much opportunity to play baseball while in the service, just an occasional recreational game.

Returning to Minnesota after his discharge, Elliott enrolled at the University of Minnesota, thanks to the GI Bill. With no home to come back to, he lived year-round in a campus fraternity house. He made the freshman football and baseball squads in the 1945–46 school year, earned three varsity letters in each sport, and was First-Team All-Big Ten as an outfielder in 1949.6 7 8 He graduated in 1949 with a bachelor’s degree in education.

Elliott played for a variety of town teams in summers while in college. Minnesota had a long and vibrant amateur and semipro baseball history. The organization now called the Minnesota Baseball Association was formed in 1924 to conduct a State Tournament, and still conducts annual tournaments today. There were 452 teams in the state in 1940. World War II brought the number down to 152 in 1945. The number soared to 411 in 1946 as returning servicemen returned, and the civilian population looked forward to returning to the pleasures of the pre-war era.9 Many towns, small and large, installed lights in the next five years, but in 1946 almost all league games were weekend daylight affairs.

Many teams scheduled midweek twilight exhibition games to provide more at-bats for players, and to raise money for field improvements and salaries. Towns frequently hired a top pitcher and other ringers to gain an advantage in these games. Elliott became one of these hired guns, receiving $25 to $50 per game, usually as a catcher. He pitched in a few, too. A Minneapolis tobacco shop and a popular sporting goods store served as clearing houses for teams and players looking for games. “I often met the umpires and a pitcher at a drug store south of downtown Minneapolis and we rode together to games,” Elliott recalled.10

Minnesota town baseball at that time was not strictly amateur. The rules did not prohibit paying salaries to players in its Class A and AA leagues. The only real difference between the two classes was that Double-A teams could have three players from outside the town boundaries, while Single-A teams could only have two. However, towns often “established” residency for outside players well in advance of them moving to town. Harry caught for Class-A teams in Anoka in 1947 and for Watertown, his hometown, in 1948. He pitched a few games for Watertown, and hit in the high .400s both seasons.

His reputation earned him a 1949 contract with Atwater, a small farming town 90 miles west of Minneapolis and in the middle of summer lake cabin country. The town had decided to move into the “big leagues” of Minnesota baseball and joined the West Central Minnesota League that had just moved up to Class AA. That would put them up against much bigger towns like Benson and Willmar, which had more sponsors and resources to fund and support their teams.

Based on a check register for the 1949 Atwater team, Elliott was paid $212.50 per month to catch that summer.11 His hitting and aggressive play electrified the small town. “Everyone in town knew who he was,” a teammate later recalled. “They talked about him for years. … They called the season ‘The Elliott Year.’ It was like having Babe Ruth in Atwater.”12 Harry was drafted by league champion Benson to play for them in the State Tournament. He hit three home runs in the first game of the tourney and batted 6-for-10 in three games.13

Shortly after the tournament Elliott moved to Austin, Minnesota to begin a teaching career. He was also an assistant football and head baseball coach. Austin, coincidentally, had just won the 1949 Double-A championship at the State Tournament. Harry didn’t think he was recruited to Austin because of baseball, but it is hard to believe that it was not part of the hiring discussions. Austin played in the Southern Minnesota League, acknowledged as the strongest Double-A league in the state, and promised to have a stronger team in 1950.

Austin repeated as league champions, with a roster dominated by former minor league professional players. None of the players were from Austin. Twelve of the 14 men on the 1950 State Tournament roster were former pros — two had played in Triple-A; three in Double-A; four in Single-A; and three in Class C. The other two were college players—Elliott and Bill Skowron, a sophomore football and baseball star at Purdue who had led the Big Ten in hitting in 1950. Skowron played third base for Austin, and worked for Austin manager Emil Scheid’s plumbing business during the summer, earning $400 per month. He hit .343 for the season, and his power attracted major league scouts.14

How strong was the Southern Minny League? “I think Austin would have made a good Double-A pro team,” Skowron said. “They had great pitching in that league. It was a hell of a league. It sure was a break for me to play in that league.”15 He signed a contract with Yankees scout Joe McDermott for a reported $25,000 on Emil Scheid’s living room table prior to the Minnesota State Tournament.

Skowron’s contract got Harry Elliott thinking about pro baseball. “My batting average at the time [.390] was better than Bill’s,” he later told Minneapolis Tribune columnist Sid Hartman, “and I felt I was his equal as a ball player.”16 He also thought the Korean War draft gave him an opportunity, despite his age. “I figured this was a good time to try, what with so many fellows being called into military service.”17 He talked to a few scouts, but most thought him too old—he would be 27 in December—and too small. Although he had a muscular build, his 5-foot-9 height turned many of them off.

Nevertheless, he resigned his teaching job at the end of October, and went to stay with his mother in Wisconsin, hoping to hear good news from Yankees scout Joe McDermott or Joe Mathes of the St. Louis Cardinals.18

Neither offered him a contract, but a friend from Austin contacted an acquaintance in the Panama Canal Zone, and prompted Mathes to help get Harry signed with Balboa in the winter Canal Zone League. Cardinals scout Harrison Wickel looked at him during that season, but only offered to sign him to a low minor league contract. However, veteran minor leaguer Al Kubski, who was player-manager for the league-champion Cristobal Mottas, recommended Harry to Shreveport owner Bonneau Peters, who signed him for his 1951 Double-A Texas League team.

Elliott hit 9-for-21 in six games with Shreveport, but then was optioned to Alexandria, Louisiana in the Class C Evangeline League. A Shreveport scout suggested he concentrate on playing outfield instead of catching because he said it would be a faster way to get to the majors. He led the league with 221 hits, 52 doubles, and a .391 batting average. He married Mary Louise Field after the season. They had met while he lived in Austin, and the newlyweds traveled to Venezuela. There Harry played winter ball with the Vargas team, which included six players from the Texas League. He had a solid season there, hitting .320 in 181 at bats.19

He played every game for Shreveport in 1952, racking up 104 RBIs and a league-leading 204 hits in 635 at-bats; he finished second in the league with a .321 batting average. He began wearing glasses in June because of astigmatism, and his first son was born on July 20.

The Cardinals purchased him from Shreveport for $30,000 in December, but listed him as property of their Houston, Texas League farm team. (They did not want to add him to their 40-man major league roster at that time.)20 “They could have purchased me for nothing in 1950,” Harry laughed.21 He played for Vargas again in the Venezuelan winter league. He was among the league leaders with a .316 batting average in 171 at bats.22

Elliott started slowly for Houston in 1953 but worked his way up to a .309 batting average by the end of May. When the Cardinals purchased him from Houston on July 31, he was third in the league with a .328 BA and was leading the league in hits. He had not been discouraged by his slow start, and told Houston writers he was in a hurry to get to the majors. “I’ll get going,” he said. “I know I will, and I’m going to the majors. And when I get there, I’m going to stick.”23

It seemed like Elliott might have a real opportunity to break into the starting lineup in St. Louis. The Cardinals had a good post-WWII run, winning the World Series in 1946, and finishing in second place from 1947–1949. They fell to fifth place in 1950, but recovered somewhat with third place finishes in 1951 and 1952. However, the team was growing old. The average age of the eight position players in 1952 was 31.5 years. Their three outfielders—Stan Musial, Peanuts Lowrey, and Enos Slaughter—were 31, 34, and 36 years old, respectively.

When Elliott joined the team at the end of July, the Cardinals were in a virtual tie for fourth place with the Giants, and were not competitive against the league-leading Dodgers. The Cards had lost four straight to the Dodgers at Ebbets Field on July 16-18, and were outscored 44–12 in the series. New team owner August A. Busch Jr. emerged from emergency organizational meetings in the last week of July to issue a new three-year contract to player-manager Eddie Stanky. “I want to start rebuilding right now,” Busch said. “I can take the criticism if we fall back before going up, but I want my manager to have guts, too, and the thing to do is give him security.”24

Elliott made his first major league appearance on August 1, striking out as a pinch hitter against the Dodgers’ Preacher Roe. He started ten consecutive games from August 14–23. He hit 6-for-17 in the first four games at Cincinnati, but only 1-for-15 in the next six games. Manager Stanky was optimistic about Elliott’s chances to be Enos Slaughter’s replacement. “He came up with a better reputation as a hitter than a fielder, but he has showed me more in the field,” Stanky commented. “And that’s good, because I’m sure he’ll hit. He knows the strike zone, but he just has been over-eager.”25

However, Harry was used sparingly the rest of the season. He played in 12 of the team’s last 34 games, but only five as a starter. He finished the season with a .254 BA in 59 at bats. His best game was on September 1 when he went 3-for-4 in Brooklyn, including a payback homerun off Preacher Roe.

Though disappointed that he had not played more in St. Louis, Elliott was looking forward to 1954. He thought he would be with the Cardinals for a while, and decided to forgo playing winter ball and do public relations work for Budweiser in Minnesota. “I played winter ball for the money and to keep in shape as much as for the experience,” he said.26

He reunited with Bill Skowron and his 1950 Austin, Minnesota teammates to play an exhibition game against Russ Meyer’s National League All-Stars on October 11 in Rochester, Minnesota. Meyer’s roster included Rip Repulski, Ted Kluszewski, Roy McMillan, John Wyrostek, Carl Erskine, and others. Austin, the 1953 Minnesota Double-A champs, beat the All-Stars 11–10, with Skowron hitting two home runs and Elliott hitting one.27

Elliott signed his contract early and asked to join the Cardinals’ special early training camp when it began on February 12, 1954 in DeLand, Florida. Pitchers and catchers were not scheduled to report to the team’s regular training camp in St. Petersburg until February 19, while the others reported on February 26.

Elliott didn’t get much of a chance in spring training, however. Manager Stanky was taking a close look at rookie outfielder Wally Moon as the eventual replacement for Enos Slaughter, who would turn 38 in April. Harry played in only one of 30 exhibition games—with only one at bat. He admitted he did not get along very well with Stanky. “Maybe I was too much like him, he said.”28 And when Stanky told him he was going to option him down to the minors, Harry got angry and complained about his lack of playing time. “What good is it going to do for me to lead another minor league in hitting?” he asked Stanky, who replied, “You had your chance when you had 59 at-bats last fall.”29

Elliott reported to San Diego just two days before the start of the Pacific Coast League season, and Padres manager Lefty O’Doul figured he might need a lot of batting practice. “Do you want to sit on the bench for a few days at the start?” O’Doul asked. “No, I came here to play and that’s what I’d like to do,” Harry told his new boss.30

“So the day before the season started Elliott got one of the pitchers to hurl to him for a couple of hours, and he got in a lot of hitting practice.”31 Even though he had had only one at-bat under game conditions since the exhibition game back in October, Harry showed no rust the next day, hitting 2-for-4 in each game of the season-opening doubleheader on April 6. He hit 15-for-32 the first week.

His hitting and aggressive play immediately made him a crowd favorite. San Diego Evening Tribune sportswriter Earl Keller wrote in The Sporting News that “He promises to join Max West, Jack Graham, Orestes Minoso and Harry Simpson on the list of greatest crowd-pleasers ever to wear San Diego uniforms.”32 He also impressed manager O’Doul by volunteering to catch in three games when an injury left the team with no backup for a short time.

Elliott led the league with a .350 batting average, and he also topped the league with 224 hits, 319 total bases, and 42 doubles. He also drove in 110 runs. The Padres tied the Hollywood Stars with a 101–67 record and won a one-game playoff, 7–2, to earn their first pennant since joining the league in 1936. (The team had won the playoffs in 1937 after finishing the regular season in third place.)

Crowds returned to Lane Field, too. The team drew 439,646 when they finished in second place back in 1950, but attendance dropped dramatically when the team finished sixth, fifth, and sixth, respectively, in 1951–1953. The Padres’ 1954 season attendance of 292,487 topped 1953 by 123,870. More than 11,000 fans had packed Lane Field for the playoff game. Capacity at the time was about 8,000. Padres pitcher Ed Erautt remembered fans standing along the outfield wall. “They had to rope the field off,” he said in a 2004 interview. “Anything hit over the rope was a double.”33 The city celebrated with a parade down Broadway to Horton Plaza. The playoffs were a letdown after the excitement of the pennant run, and the Padres lost two straight to Oakland in the best-of-three first round.

Elliott was ready to move and decided to keep sharp by playing winter ball again, this time in Cuba. He felt good about his chances with the Cardinals in 1955. Enos Slaughter had been traded to the Yankees in early 1954, and there was talk about moving Stan Musial (who was just turning 34) to first base. A third outfield position seemed open, assuming Rip Repulski and Rookie-of-the-Year Wally Moon had two slots sewn up. Elliott’s competition would be left-handed-hitting Bill Virdon, who was obtained from the Yankees in the Slaughter trade. Virdon led the Triple-A International League with a .333 BA and was praised for his speed and defense.

Cards’ manager Eddie Stanky had been no fan of platoon baseball. The 1954 outfield—Repulski, Moon, and Musial—started 149, 148, and 153 games, respectively. However, in a post-season review, Stanky said he was considering a two-platoon system, and listed Elliott as part of a right-handed-hitting team. “I didn’t give Harry much of a shot last spring, but he certainly merits one now,” Stanky explained. “The guy has hit in every league he has played in.”34

The Cardinals sent top prospects Bill Virdon, Ken Boyer, Don Blasingame, and three others to play for Havana in the four-team Cuban League, where they would be tutored by two Cuban legends, Miguel Gonzalez and Dolf Luque. Elliott was apparently not invited to play for Havana, but signed with Cienfuegos. He got off to a good start, hitting in the low .300s, but dropped out of the league’s top ten by the end of the season. Virdon, at .340, ranked third on the list.35

Cardinal scout Gus Mancuso made a trip to Havana and was impressed by Virdon.36 Bobby Bragan, manager of first-place Almendares, may have influenced Mancuso when he told him that “Bill is of major league caliber ‘right now.’ ”37 Bragan had managed the Hollywood Stars in the Pacific Coast League in 1954, who played 25 games against San Diego. You would think Bragan might have said something about Elliott, too, but if he did, Mancuso chose not to mention it.

However, The Sporting News staff writer Clifford Kachline listed Harry as one of the Cuban League standouts expected to make major league jobs in 1955 in his January 12 article on winter leagues.38

Elliott, unlike 1954, was now on the Cards’ spring training roster. He signed his 1955 contract as soon as he got back from Cuba, and reported to camp early. Manager Eddie Stanky gave Harry playing time in exhibitions, but it was obvious that he was grooming Bill Virdon to be his starting center fielder. Elliott was a steady hitter throughout spring training, while Virdon was struggling.

Nevertheless, when the team broke camp to begin a 10-game barnstorming trip—eight games with the White Sox and two with the Tigers—on their way to St. Louis, Stanky announced that Stan Musial was moving to first base and that Virdon would be his center fielder, with Rip Repulski in left and Wally Moon in right. At that time Elliott was hitting .333 (8-for-24 in 12 games) compared to Virdon’s .143 (4-for-28 in 12 games). Stanky explained that Virdon had a reputation as a slow starter, and he expected him to hit. “If he doesn’t,” Eddie said, “I’m prepared to two-platoon.”39

Virdon’s bat came alive somewhat in those last games. Elliott entered one game late as a defensive replacement, pinch hit four times, and remained in the game for two more at-bats after the fourth pinch-hitting appearance. He had two hits in the six-at-bats, but Stanky was trying to get the team ready for opening day. He started Moon, Virdon, and Repulski in the outfield every game and it was obvious that Elliott’s role with the team would primarily be as a right-handed pinch hitter and spot starter.

Virdon started the season by going 6-for-15 in the first three games, but then was sidelined by a throat infection. Elliott replaced him for the next six games, starting with 4-for-4 and 3-for-4 in an April 17 doubleheader with Chicago. Harry hit 9-for-22 in the six games, but pulled a muscle late in a game on April 23. Virdon ran for him in that game, and moved back into the starting lineup. He kept hitting well and doomed any chance for Harry to get more action in a righty-lefty platoon system. Virdon was hitting .307 at the All-Star break, finished the season at .281 and was voted Rookie of the Year. Harry was hitting .288 at the break—21-for-73 in 42 games, 15 of them as a starter.

Stanky was fired after the May 27 game and replaced by Harry Walker. The managerial change did not help: the team was 17–19 under Stanky, and 51–67 under Walker. The change seemed to benefit Elliott at first. The Cards faced left-handed pitchers six times in a 13-game stretch from May 30 to June 12. Walker started Harry in right field in all six games against lefties—five in place of the lefty-swinging Virdon and once in place of Moon, who also batted left.

Elliott hit 6-for-18 in the six games, but the platooning essentially ended there. He started in only nine of 102 games the rest of the season. He had played in 21 of the team’s 36 games under Stanky, but only 47 of 118 under Walker. Elliott finished with a .256 batting average, 30-for-117 in 68 games. He hit .311 in the 22 games he started, 23-for-70, but only .179 as a pinch hitter.

“Stanky promised me he’d find another team for me,” Harry said. “But when he got fired that didn’t happen.”40 The team’s farm director, Walter Shannon, hinted at the plan for Elliott in an August visit to Minneapolis. “Harry Elliott is a great Triple-A player, but he’s getting old and we’re building with youth,” he told columnist Sid Hartman. “We may trade or sell him.”41

Elliott took a job after the season to teach physical education and coach basketball at Soldan High School in St. Louis. He decided not to play winter ball, but planned to quit the teaching job in time to report to spring training. He appeared on the March 5, 1956 cover of the Sports Illustrated “Spring Training” issue. The photo showed cameramen in the foreground, and five Cardinals pantomiming leaping for a ball—Elliott, Virdon, Repulski, Moon, and Musial. However, by the time the magazine hit the stands Elliott had been sold to San Diego. He had not been on the Cardinals spring training roster and did not play with them in any exhibition games.

Elliott got off to a very slow start with the Padres. He was hitting just .231 after five weeks. Pacific Coast League writers thought he “has become a victim of ‘big league thinking.’”42 When he won the league batting title in 1954 he had sprayed hits—224 of them—to all fields, but Cardinals managers Stanky and Walker tried to get him to become a pull hitter. They told him “he’d never be a major leaguer until he learned to pull the ball.”43 New Padres general manager Ralph Kiner began to work with him to find his old style. Elliott eventually recovered his touch and finished the season at .291, but that ranked only 33rd in a league that had a composite .273 batting average.

Harry signed to play winter ball with Oriente of the Venezuelan Association. He was one of eight Triple-A and Double-A players on the roster, and one of 40 players in the four-team league with experience in Organized Baseball. He was not on the list of the top 14 hitters published in the March 13, 1957 issue of The Sporting News, and it is not known how many games Elliott may have played during the season.

Elliott’s 1957 season was a disaster. He fractured his left ankle during spring training with San Diego, and was still in a cast when his contract was sold to Pacific Coast League rival Vancouver. He played his first game on June 21, but was shipped to San Antonio of the Double-A Texas League in late July. He hit only .245 for Vancouver in 18 games, and .238 for San Antonio in 45 games.

He made the decision to retire in 1958, after his contract yo-yoed from San Antonio to Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League, and then to Little Rock and Chattanooga of the Double-A Southern Association. He played 40 games at Little Rock and 17 at Chattanooga.

Elliott began teaching in 1959 at El Cajon Valley High School, in the northeastern suburbs of San Diego. He coached baseball until he retired in 1986, and also coached football, soccer, and freshman basketball for many years.

When asked to reflect on his baseball career in an interview in 2008, he hesitated. “That’s a tough one,” he said. “I feel I lost my big chance in 1954. If I could have played that year with the Cards, I think I would have done well enough to stick in the majors for four or five more years.”44

Could he have done anything differently, like starting pro ball earlier? “I don’t know,” he said. “I just don’t know . . . There was a war going on when I graduated high school in 1942 . . . and I just didn’t think about the future. I figured I would be in military service.”45

Didn’t anyone approach him about playing pro ball? “I was a pretty cocky guy and a pretty good athlete,” he said, “but no one ever told me I should be a pro ballplayer. I did not see a scout until one from Pittsburgh talked to me at the 1949 Minnesota State Tournament, but he didn’t make me an offer.”46

What if Elliott had started his baseball career earlier and hit .350 in the Pacific Coast League, say, in 1949 instead of 1954? He would have finished ahead of three players who made the major leagues in 1950—Walt Dropo, who became the Rookie of the year with the Boston Red Sox; Al Rosen, who hit 37 home runs for Cleveland; and Irv Noren, who hit .295 for Washington; as well as Minnie Minoso, a nine-time All-Star who broke into the majors in 1951.

Of course, we can never know. What we do know is that he was a pretty good ball player, but is on the big list of countless other Americans who had their lives drastically altered by WWII.

Elliott retired in Yuma, Arizona, and had been active there for years, playing tennis and bowling. He’d had several surgeries, however, and at the time of the interview said he was having trouble getting around. He died on August 9, 2013 at a nursing home in Little River, Kansas, with his family by his side. He was survived by five sons and one daughter. He was preceded in death by one son and former wife, Mary Louise.47

Minnesota towns mentioned in this biography and their population

|

Lester Prairie |

423 (1940) |

|

Watertown |

737 (1940) |

|

Anoka |

7,396 (1950) |

|

Atwater |

880 (1950) |

|

Benson |

3,398 (1950) |

|

Willmar |

9,410 (1950) |

|

Austin |

23,100 (1950) |

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Chris Rainey and Rory Costello, and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Johnson, Lloyd and Miles Wolff, ed. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Baseball America, 1997).

Peterson, Armand and Tom Tomashek. Town Ball: The Glory Days of Minnesota Amateur Baseball (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

Austin (Minnesota) Daily Herald

Brainerd (Minnesota) Dispatch

Carver County (Minnesota) News

Minneapolis Tribune

San Diego Union-Tribune

Sports Illustrated

The Sporting News

Baseball-reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Hennepin County (Minnesota) Library; Ancestry Library Edition.

US Bureau of the Census, “Census of the Population,” 1930, 1940, and 1960.

Harry Elliott, telephone interviews with author, April 22 and 27, 2008.

Bill Skowron, telephone interview with author, May 7, 2003.

Notes

1 Harry Elliott, telephone interviews with author, April 22 and 27, 2008.

2 The family’s residence on April 1, 1935 was listed as Sonoma, California in the 1940 Federal Census.

3 Carver County [Minnesota] News, May 28, 1942.

4 Ibid.

5 Harry Elliott interview.

6 “Baseball Archives,” gophersports.com, https://gophersports.com/sports/2018/5/21/sports-m-basebl-archive-minn-m-basebl-archive-html.aspx, accessed June 24, 2019.

7 “2018 Football Media Guide,” gophersports.com, https://gophersports.com/documents/2018/7/27/2018_FB_Media_Guide_web.pdf, accessed June 24, 2019.

8 “All-Time Letterwinners,” Baseball Archives, gophersports.com, https://gophersports.com/sports/2018/5/21/sports-m-basebl-spec-rel-minn-m-basebl-letterwinners-html.aspx, accessed June 24, 2019.

9 Peterson, Armand and Tom Tomashek. Town Ball: The Glory Days of Minnesota Amateur Baseball (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 128.

10 Harry Elliott interview.

11 Kandiyohi County (Minnesota) Historical Society.

12 Peterson and Tomashek, Town Ball, 254.

13 “1950 Northwest Umpires Association Official Handbook,” author personal copy.

14 Peterson and Tomashek, Town Ball, 249.

15 Bill Skowron, telephone interview with author, May 7, 2003.

16 Sid Hartman, “Skowron’s Big Bonus Spurs Elliott into Pro Baseball,” Minneapolis Tribune, August 22, 1953.

17 John Lyons, “Elliott Helping Cards Correct a Mistake of ’50,” The Sporting News, May 20, 1953, 29.

18 Tom Koeck, “In the Press Box,” Austin [Minnesota] Daily Herald, November 4, 1950, 5.

19 “Venezuelan Leaders,” The Sporting News, February 13, 1952, 29.

20 “Cards Buy Grant Dunlap, Texas League’s Bat Leader,” The Sporting News, December 10, 1952, 15.

21 Hartman, “Skowron’s Big Bonus.”

22 “Venezuelan Leaders,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1953, 25.

23 Lyons, “Elliott Helping Cards.”

24 Bob Broeg, “’Rebuild With Youth,’ Stanky’s Long-Term Card Assignment,” The Sporting News, August 12, 1953, 4.

25 Bob Broeg, “It’s an Old Cardinal Custom – ‘Leaning on Their Lefties,’ ” The Sporting News, September 2, 1953, 9.

26 Harry Elliott interview.

27 “Austin Nips Major Leaguers, 11–10,” Austin [Minnesota] Daily Herald, October 12, 1953, 1

28 Harry Elliott interview.

29 Harry Elliott interview.

30 Earl Keller, “Harry Elliott Wins a Warm Welcome With Hot Hitting,” The Sporting News, April 28, 1954, 23.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 Anthony Tarantino, “Five decades ago, the PCL Padres won a one-game playoff to finish on top of the minor league world,” San Diego Union-Tribune, September 13, 2004, http://signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20040913/news_1s1dtown.html, accessed March 25, 2005.

34 Bob Broeg, “Brat Sees Platoons as Likely Cure for What Ails Redbirds,” The Sporting News, October 6, 1954, 15.

35 “Cuban Season Leaders,” The Sporting News, February 16, 1955, 27.

36 Pedro Galiana, “Mancuso Labels Card Rookie Trio in Cuba ‘Ready,’” The Sporting News, December 29, 1954, 25.

37 Ibid.

38 Clifford Kachline, “Winter Leagues Boast Fine Crop of Prospects,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1955, 21.

39 Bob Broeg, “Stan the Team-Man Makes Way for Virdon in Outfield,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1955, 5.

40 Harry Elliott interview.

41 Sid Hartman, “The Roundup,” Minneapolis Tribune, August 31, 1955, 20.

42 “Big Time Coaching Blamed for Harry Elliott’s Slump,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1956, 25.

43 Ibid.

44 Harry Elliott interview.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 Harry Lewis Elliott Memorial Page, Birzer Funeral Homes, Lyons, Kansas; https://www.birzerfuneralhomes.com/notices/Harry-Elliott, accessed August 3, 2014.

Full Name

Harry Lewis Elliott

Born

December 30, 1923 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

August 9, 2013 at Little River, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.