Ben Cantwell

Considered one of the “smartest” hurlers of his era, Ben Cantwell jumped from the Class B Jacksonville Tars to debut in the major leagues with the New York Giants in 1927.1 Traded the following season to Boston, he earned his reputation as a versatile pitcher for the Braves, winning 20 games in 1933. Just two seasons later, Cantwell lost 25 games (the last major-league pitcher to lose that many) during the Braves’ forgettable 1935 season, in which they won just 38 times.

Considered one of the “smartest” hurlers of his era, Ben Cantwell jumped from the Class B Jacksonville Tars to debut in the major leagues with the New York Giants in 1927.1 Traded the following season to Boston, he earned his reputation as a versatile pitcher for the Braves, winning 20 games in 1933. Just two seasons later, Cantwell lost 25 games (the last major-league pitcher to lose that many) during the Braves’ forgettable 1935 season, in which they won just 38 times.

Born on April 13, 1902, in Milan in western Tennessee, Benjamin Caldwell Cantwell was the 12th and final child born to Orlando Festers and Elizabeth Haiden (Baron) Cantwell. A veteran of the Civil War from Indiana, Orlando married Elizabeth in 1878, and together they moved to Milan, a small railroad outpost where Orlando worked as a telegraph operator. By all accounts a quiet and studious type, Ben attended Milan High School, where he excelled in the classroom as well as on the athletic field. The tall right-hander was offered a scholarship to attend the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, which he entered in 1921. In addition to playing basketball and specializing in the long jump on the track and field team, Ben pitched and played first base for coach M.B. Banks on the baseball team for four years (1922-1925) and served as an unofficial coach in his final year. A member of the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity, he graduated in 1925 with a degree in commerce.

Cantwell’s professional baseball career began during his college days. After his sophomore year he had a successful tryout with the Paris Parisians in the Class D Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee (Kitty) League in 1923. Located about 40 miles from Cantwell’s hometown, the Parisians boasted at least two other future major leaguers, Jim Turner and Herb Welch. After a year playing semipro baseball in the coalfields of Pennsylvania in 1924, Cantwell pitched for the Jackson (Tennessee) Giants in the Class D Tri-State League in 1925.2

Cantwell’s fortunes changed when he signed with the Sanford Celeryfeds in the Class D Florida State League in 1926. At 6-feet-1 and approximately 165 pounds, Cantwell did not cut an imposing presence on the mound, but he made up for it with his cerebral and deliberate approach to pitching. He led the league with 24 wins, lost just five contests, and proved his durability by logging 285 innings, while the Celeryfeds won the league championship. Despite Cantwell success, local scouts were unimpressed, primarily because he lacked a daunting fastball. “He’s just a good bush-league pitcher who hasn’t enough stuff to deliver in the big leagues” was the consensus at the time.3 During the season Cantwell met LeClaire Jones, whom he married the following March.

Basking in the regional publicity of his outstanding season, Cantwell was drafted after the season by the Jacksonville Tars in the Class B Southeastern League. Working closely with manager Tommy McMillan, a former Brooklyn Dodger, Cantwell possessed a smooth “easy delivery,” an excellent curveball, and an assortment of off-speed pitches. “This boy looks like a real pitcher,” reported the New York Times about Cantwell’s pitching performance in a fateful exhibition game against the New York Giants in March 1927.4 With his batterymate, future Hall of Famer Al Lopez, Cantwell started the season opener for the Tars and reeled off 11 consecutive wins. By midsummer, scouts could no longer afford to overlook “Bear-Cat” Cantwell, as fans and teammates called him.5 Lopez recalled that six to eight scouts followed Cantwell wherever he pitched and team president Charles B. Greiner was inundated by inquiries about his asking price for the star pitcher.6

Several developments help explain the increased attention Cantwell received. Due to changes in baseball’s draft system in 1921, major-league teams were no longer able to draft prospects from the three highest minor leagues at a set price. An unprecedented bidding war and spending spree ensued throughout the decade, led especially by the prosperous teams, the Yankees, Giants, and Cubs. Consequently, scouts began scouring the lower minor leagues (Class A and Class B) for capable and relatively inexpensive players. Though it was uncommon for players to make the jump from Class B to the major leagues, one well-publicized success story took place in 1927, a fortuitous time for Cantwell. Thirty-year-old rookie pitcher Wilcy Moore, signed by the Yankees, was in the midst of a well-publicized career year as an invaluable reliever and spot starter. Not wanting to be outdone by their metropolitan rivals, New York Giants owner Charles Stoneham dispatched scout Dick Kinsella to see Cantwell pitch against the Montgomery Lions in Alabama. Willing to take a chance, Stoneham bought Cantwell’s contract for an estimated $25,000, reportedly the highest ever paid for a Class B player.7

Reporting to the Giants on August 6, 1927, after posting 25 wins for Jacksonville, Cantwell made his major-league debut in a loss to the Pirates on August 19, tossing 2? innings of two-hit, no-run ball in relief. With his “careful style of pitching” and “confusing” pitches, Cantwell hurled a complete game against the reigning champion Cardinals in St. Louis on September 14 to notch his first major-league victory.8

“Cantwell Corners Glory on His Day,” read a headline in the New York Times on March 13, 1928, after the 25-year-old pitcher held his former Jacksonville teammates to two hits over five innings in an exhibition game in Florida.9 It appeared as though Cantwell would carve out his niche in New York, but the depth of the Giants’ pitching staff (including eventual 20-game winners Larry Benton and Freddie Fitzsimmons and the young Carl Hubbell) made it difficult to earn the confidence of manager John McGraw. After just seven appearances and one win through June 10, Cantwell was traded to the Boston Braves on June 15 along with pitchers Virgil Barnes and Bill Clarkson and catcher Al Spohrer for pitcher Joe Genewich. Used primarily as a reliever and spot starter after the trade, Cantwell entered the starting rotation permanently on August 29 when the “Giants castoff [got] his revenge” by defeating the Giants in the Polo Grounds in an impressive complete-game victory.10 He tossed two more complete-game victories in September to finish with a 3-3 record and a 5.10 earned-run average in 90 innings with the Braves.

The Braves’ owner, Judge Emil Fuchs, an attorney with no practical baseball background, sold player-manager Rogers Hornsby after the 1928 season in order to remain financially solvent and named himself manager for the 1929 season. The results were disastrous. The Braves finished in last place with a 56-98 record and Cantwell floundered, wining just four times in 17 decisions and registering a 4.47 ERA in 157 innings as a part-time starter and reliever.

Cantwell’s career received a boost when Fuchs hired former Pirates and Cardinals manager Bill “Deacon” McKechnie, a master handler of pitchers. Prizing durability and flexibility in his moundsmen, McKechnie wanted pitchers who issued few bases on balls and surrendered few home runs. Instead of brilliance, McKechnie preferred intelligent veteran pitchers. Cantwell fit this description perfectly. In his first season under McKechnie, the 28-year-old Cantwell, starting in 21 of his 31 appearances, won 9 and lost 15 on a terrible-hitting team (seventh in the eight-team NL) and sported a 4.88 ERA, which was just a notch better than the league average in the memorable “Year of the Hitter.” Three of his victories were against the Giants.

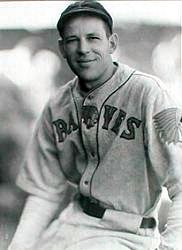

Used mainly out of the bullpen for the first half of the 1931 season, Cantwell was tabbed to start the second game of a doubleheader in Pittsburgh on July 18. “Cantwell Hurls Boston to 1-0 Shutout,” read a subhead after he tossed his first major-league shutout, cracked three singles, and scored the only run of the game.11 A capable hitter, Cantwell batted .231 in his career (116-for-503), including a career-high .302 in 1930. After suffering a tough loss to the Giants despite pitching a complete game and surrendering just seven hits on September 1, Cantwell tossed one of the best games in his career five days later, a shutout at the Polo Grounds. “Cantwell Gives only Four Hits to McGrawmen,” read the subhead in the New York Times and included an image of the hurler with his square jaw, chiseled facial features, and serious look.12

Surprising baseball by going 77-77 for their first nonlosing season since 1921, the Braves boasted the league’s second-best ERA (3.53) in 1932. Moved to the bullpen because of his ability to warm up quickly and pitch effectively with limited rest, Cantwell was the National League’s best relief pitcher, registering nine of his 13 wins while posting a 2.03 ERA in relief. Able to start on a day’s notice, Cantwell posted a career-high 12?-inning outing against the Cubs in an extra-inning loss on June 12. He replaced Socks Seibold in the starting rotation in September and concluded the season by pitching three consecutive complete-game victories, including a seven-hit shutout of the Cubs to avenge his earlier tough-luck defeat. Once described as “small but efficient looking,” Cantwell finished the season with a 13-11 record and 2.96 ERA (and a career-high 128 ERA+) in 146 innings.13

Following their franchise record-setting attendance mark of 515,005 in 1931 with 507,606 (third-best in the National League) in 1932, the Braves and their fans anticipated an even better season in 1933. “It’s not a particularly imposing team,” McKechnie admitted in spring training, “but I’ve got some pretty good pitchers. Give me four first-string pitchers and I’ll make trouble in any league.”14 The team got off to a slow start (nine games under .500 after 53 games), and one of its lone bright spots through June was Cantwell, who had accounted for ten of the Braves’ 34 victories. On July 9 the Braves evened their record at 39 wins and 39 losses behind Cantwell’s ten-inning complete-game 3-2 victory over the Cincinnati Reds. Called a “slow ball expert” and a “wizard for control,” Cantwell was a lowball pitcher who threw a deceiving screwball and fluttering knuckleball (unlike the hard knuckleballs of the time).15

With a 22-6 record in August, culminating with Cantwell’s complete-game, NL-leading 19th victory over the first-place Giants on August 31, the Braves were suddenly in a pennant race. Trailing the Giants by just five games, they were a season-high 15 games over .500, and evoked memories of George Stallings’ World Series champion “Miracle Braves” from 1914. And then September arrived.

The Braves’ surge corresponded with the best stretch in Cantwell’s career. From June 30 to August 31 he won ten games, pitched 11 complete games, and lost just four times (all consecutively, when he was provided just five total runs of support). After five unsuccessful attempts to win his 20th game of the season, Cantwell finally notched the elusive win on September 26 when he defeated the Giants, tossing his fifth consecutive complete game in three months against them. Slumping to 12-16 in September, the Braves concluded the season with an 83-71 record, their best since 1916, and set a new attendance record (517,803) that they would not break until 1946. Joining Carl Hubbell, Dizzy Dean, and Guy Bush as the senior circuit’s only 20-game winners, Cantwell finished with career highs in wins (20, including winning streaks of seven and eight games), innings pitched (254?), and complete games (18), and registered his lowest ERA (2.62).

Because of Emil Fuchs’s mounting financial difficulties, the Braves reported to their spring training site in St. Petersburg, Florida, with just 22 players in camp in 1934. The exciting atmosphere filled with dreams of another winning season changed when Cantwell noticed pain in his elbow. He had developed bone spurs (growths over the bone in his elbow) that affected his motion and delivery and caused excruciating pain. Advised to undergo potentially season-ending surgery, Cantwell chose to pitch in pain for the rest of his career.16 On May 20 he notched his first win of the campaign by pitching arguably the best game of his career, a ten-inning shutout of the Reds, surrendering just four hits. However, his success proved illusory; with increasing pain and no longer able to warm up as quickly or pitch as often, Cantwell struggled for most of the season and finished with a disappointing 5-11 record and a 4.33 ERA in 143? innings.

Perhaps unfairly, Cantwell is most remembered for his season in 1935 when he lost 25 games and won just 4 times; however, his season requires context. Unbeknownst to the Braves at the beginning of the 1935 season, Judge Fuchs was nearing bankruptcy. His acquisition of the ailing, 40-year-old Babe Ruth as player, vice president, and assistant manager to start the season was nothing more than a ruse to sell tickets. Ruth’s poor play (especially his fielding) was divisive in the clubhouse and affected the morale of the team, which was otherwise essentially the same from 1934. After winning five of 12 games to start the season, the Braves lost 20 of 24 in May when the most memorable game of their season occurred. In a loss to the Pirates on May 25 in Pittsburgh, Babe Ruth walloped three home runs. Ruth retired a week later. Somewhat befittingly, Cantwell was charged with the loss in that historic game. The losses kept mounting for the Braves and Cantwell, who lost his 13th consecutive game on July 19 after starting the season with a complete-game victory over the Brooklyn Dodgers. In nine of those losses, he was backed by a total of 13 runs as a starting pitcher.

With the club in disarray, Fuchs sold the team on July 31 to minority owner Charles Adams; however, the team’s sale and its unclear future only made matters worse. The Braves went 18-69 (.207 winning percentage) over the last three months of the season to finish with a 38-115 record and a .248 winning percentage. Cantwell lost his last six decisions in September to finish with an unenviable 4-25 record. Remarkably, he was probably the Braves’ most effective pitcher despite pitching in pain the entire year. He posted the best ERA among starters (4.61), was second on the team with 210? innings pitched (in just 24 starts and 15 relief appearances), and led the team with 13 complete games.

A new ownership group, led by Bob Quinn, former owner of the Boston Red Sox, took over the Braves in 1936. In order to start fresh and forget the disastrous 1935 season, management changed the name of the team to the Bees and Braves Field was renamed National League Park, affectionately called the Bee Hive. Primarily a relief specialist in 1936, Cantwell started occasionally, often in doubleheaders. On August 2 he went the distance to beat the Cubs 3-2 in a contest that proved to be his last victory and complete game in the major leagues. Out for five weeks in August and September, Cantwell concluded the season with a 9-9 record and a 3.04 ERA (126 ERA+) in 133? innings, including 11 starts. Impressed by Cantwell’s comeback, McKechnie anticipated that he’d be a valuable piece on the Braves staff in 1937.

Waived unexpectedly in the offseason, Cantwell was purchased by the Giants in January 1937 and assigned to their affiliate in the International League, the Jersey City Giants, where he surprisingly flourished, winning 12 of 19 decisions and posting a league-leading 1.65 ERA in 175 innings through late July and earning a call-up to the parent club. But after a disastrous start against the Cardinals, in which he surrendered four runs and six hits in four innings, the Giants sold him to the Brooklyn Dodgers, where he made his last 13 major-league appearances as a reliever without a decision.

Cantwell split the 1938 season with a Pirates’ affiliate, the Montreal Royals, where he played for former teammate Rabbit Maranville, and finished the season with the Baltimore Orioles, both in the International League, and registered a combined four wins against 15 defeats with a dismal 5.47 ERA. As a 37-year-old, he signed with the Oakland Oaks in the Pacific Coast League and experienced a rejuvenation of sorts, winning 13 games in each of 1939 and 1940 and posting 3.33 and 2.56 ERAs respectively. He retired the following season after six appearances.

Ben Cantwell, the last major leaguer to lose at least 25 games in a season, concluded his 11-year major-league career with 76 victories, 108 losses, and a 3.91 ERA in 1,534 innings. He notched another 95 wins in his eight-year minor-league career. A “heady,” smart ball player, Cantwell was considered one of the gentlemen of the game.17

Immediately after retiring from baseball, Ben settled in Oakland with his wife and daughter, Charlotte, born in 1939, and worked in the burgeoning shipbuilding industry and as a steamfitter during the war years.18 A student of the game, Cantwell began coaching in the renowned Joe Stripp’s Baseball School in its six-week winter sessions in Orlando, Florida, in 1938 and continued through the late 1940s, eventually relocating to Sanford after suffering a hand injury in a shipyard. A well-respected instructor, Cantwell thought the keys to his and other pitchers’ success were strong legs. “Sore arms are caused by bad legs and bad legs are caused by a lack of running. McGraw never had … trouble with his pitchers because he ran ’em to death,” he remarked once while coaching youngsters at Tinker Field at a Stripp’s winter camp. “If your legs aren’t in shape, they get tired. You start pitching with your arm and you put too much strain on it.”19

Cantwell died at the age of 60 on December 4, 1962, in Salem, Missouri, while preparing for a baseball camp. He was buried at North Lawn Cemetery in Salem.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Baseball Almanac

Baseball Cube

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-reference.com

New York Times

Retrosheet

The Sporting News

Notes

1 The Sporting News, February, 4, 1937, 1.

2 Newspaper reports about Cantwell’s career often noted that he started playing professional baseball with the Paris (Tennessee) Parisians in 1923. Baseball-Reference.com lists him on the team’s roster, but no statistics are provided for him. Because Cantwell was still enrolled at the University of Tennessee at the time, it is possible that he played under an alias in order to maintain his college eligibility, a practice that was common at the time.

3 Newark (Ohio) Advocate, August 24, 1927, 10.

4 New York Times, March 24, 1927, 28.

5 Masillon Evening Independent, July 20, 1927, 10.

6 Wes Singletary, Al Lopez: The Life of Baseball’s El Señor (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1999), 40.

7 New York Times, August 4, 1927, 15.

8 New York Times, August 20, 1927, 11.

9 New York Times, March 13, 1928, 25.

10 Calgary (Alberta) Daily Herald, August 30, 1928, 6.

11 New York Times, July 19, 1931, S4.

12 New York Times, September 7, 1931, 9.

13 New York Times, March 9, 1933, 1. ERA+ is earned-run average adjusted to ballpark and the league ERA. Anything over 100 is considered better than average.

14 The Sporting News, December 26, 1935, 5.

15 The Sporting News, March 9, 1933, 1.

16 The Sporting News, October 4, 1934, 5.

17 Evening Independent (Masillon, OH) July 20, 1937, 10.

18 Oakland (California) Tribune, January 2, 1942, 12.

19 Milwaukee Journal, February 7, 1939, 18.

Full Name

Benjamin Caldwell Cantwell

Born

April 13, 1902 at Milan, TN (USA)

Died

December 4, 1962 at Salem, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.