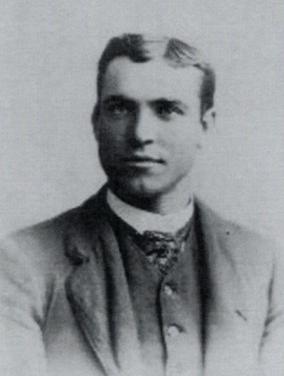

Mickey Welch

A far-from-giant Giant, pitcher Mickey Welch formed a cornerstone of the celebrated National League franchise founded in New York. Generously listed in baseball reference works as 5-feet-8 and 160 pounds, the undersized right-hander pitched and won the Giants’ [then Gothams’] inaugural NL game in 1883. Two years later, he compiled 17 consecutive pitching victories on the way to posting a 44-win season, still the all-time franchise record. By the time he departed the major league scene in early 1892, Welch had become only the third pitcher in big-league history to record 300 wins. He spent the remainder of his long life at the margins of the game, serving as a ballpark attendant at the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium, and regularly regaling New York sportswriters with tales from baseball’s early years. Some three decades after his passing in 1941 – and more than 80 years after he had appeared in his final major-league game – the memory of Mickey Welch was forever preserved by his induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Mickey Welch was born Michael Francis Walsh in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn on July 4, 1859. He was the oldest of the three siblings surviving childhood born to horseshoer John Joseph Walsh (1835-1900) and his wife, Bridget (née Guinan, c.1833-1887).1 The elder Walshes were Irish-Catholic immigrants from Tipperary about whom little else is known, except that by the time of the 1865 New York State Census, they had adopted, again for reasons unknown, the surname Welch.2 Upon entering public life, Mickey would use that as his last name, rather than Walsh, whenever dealing with baseball club owners, sportswriters, and fans, as well with as government and local officials.3

Small but athletic, Mickey spent much of his youth on the sandlots of Brooklyn, a hotbed of the pioneer-era game and home of the champion Atlantic, Excelsior, and Eckford clubs. At age 18, he journeyed upstate to accept his first professional engagement, earning $45 per month as an outfielder-pitcher for the Volunteers club of Poughkeepsie, an independent professional nine. In the box, he reportedly went 16-6 in 23 games.4

Welch began the following season with a pro club in Auburn, New York, but departed early to join the Holyoke (Massachusetts) Shamrocks in faster competition.5 He returned in 1879 to a Holyoke team upgraded by the acquisition of future Hall of Famer Roger Connor, and later major-league stalwarts Larry Corcoran, Fergy Malone, Jerry Dorgan, and Pete Gillespie. Appearing primarily as a pitcher, Welch used no windup for the mandated underhand delivery of a serviceable fastball and an effective array of breaking pitches and fashioned a 23-14 record.6 A highlight of the campaign was a 10-inning, 1-0 victory against Springfield, posted over opposing manager Bob Ferguson’s protest that Welch’s pitching motion was illegal. A competent batsman used as a backup outfielder, Mickey also hit .266 in 184 at-bats for the Shamrocks. A more enduring Welch highlight occurred off the diamond. On November 16, 1879, 20-year-old Mickey and his 18-year-old sweetheart, Mary Whelihan, were joined in marriage at St. Jerome Church in Holyoke. Their union would last 56 years and produce nine children.7

Suspect pitching motion notwithstanding, Welch had made a favorable impression on Bob Ferguson, and when the crusty veteran was appointed manager of the National League Troy Trojans in early 1880, he immediately acquired Mickey for his pitching staff. Welch was joining a middle-of-the pack club, but one loaded with young talent. No fewer than five Trojans (Buck Ewing, Tim Keefe, a hastily-released Dan Brouthers, Connor, and Welch) were destined for Cooperstown. But the club would have to endure its roster’s growing pains. Welch’s major league debut could not have gone much worse: a 13-1 loss to Worcester on May 1. Four days later, he broke into the win column, besting Worcester 3-1, and he soon justified Ferguson’s faith in him. Appearing in 65 games total, Mickey logged a 34-30 record in a yeoman 574 innings pitched for the fourth-place (41-42) Trojans. Hitting from the right side, he also batted a solid .287 in 251 at-bats, third highest on the club. But standing in the pitcher’s box a mere 45 feet from enemy batsman, Welch was shaky in the field, with a .841 fielding average.

Beginning in August, Welch occasionally was spelled in the box by a fellow rookie right-hander named Tim Keefe. Keefe went only 6-6 for Troy in 1880, but he and Welch had begun a decade-long collaboration as baseball’s most dominant pitching duo. But first, the two would have to take some lumps. Troy headed for a (39-45) fifth-place finish in 1881. That season, Keefe assumed the number-one starter role that he would maintain for most of the partnership with Welch, getting the ball in 45 games (compared to Welch’s 40 starts), but suffering an 18-27 record in 403 innings pitched. Mickey had more success, going 21-18 in 368 frames. The 2.67 Welch ERA was also better than Keefe’s 3.24. The pattern continued in 1882. Keefe drew the starting assignment more often than Welch (42 times to 33), but posted the poorer record (Keefe: 17-26; Welch 14-16). But that season the win-loss records were misleading; Keefe (367 hits surrendered in 376 innings pitched) was far more difficult to hit than Welch (334 hits given up in only 281 innings pitched). But the disparity in their win-loss records was apparently dispositive to a future employer and produced immediate consequences for Tim Keefe and Mickey Welch. And for major-league baseball in New York.

Since the expulsion of their clubs after the 1876 season, New York and Philadelphia, the nation’s two largest cities, had been without a National League team. But in 1882, the death of NL commandant William Hulbert and the emergence of the American Association, a rival major league, prompted reconsideration of the circuit’s structure. In short order, the NL liquidated the small-market franchises in Troy and Worcester, creating the needed vacancies for league reentry into New York and Philadelphia. Thereafter, both the NL and the AA began courting John B. Day, the well-heeled cigar manufacturer who controlled the New York Metropolitans, an independent, professional nine that had proved highly competitive in exhibition game play against NL and AA clubs. In time, the NL and AA each offered Day a place in their organization. Audaciously, Day accepted both offers, assigning the already-established Mets to the Association. His National League club was constructed from scratch but built around player material acquired via the fire sale of the Troy Trojans. Day plainly intended his NL team, originally called the Gothams or simply the New-Yorks, to be the favored one, and stocked it with most of Troy’s best ex-players: Buck Ewing, Roger Connor, Mickey Welch, and Pete Gillespie – but not Tim Keefe, who, in a painful misjudgment, was consigned to the Mets.

Keefe pitched brilliantly in 1883, going 41-27, with a 2.41 ERA and a league-leading 359 strikeouts in a staggering 619 innings pitched. And under the direction of wily manager Jim Mutrie, the Mets posted a more-than-respectable 54-42 record. Meanwhile, the Gothams got off to an auspicious start. With the Polo Grounds packed with 12,000 fans (including former president Ulysses S. Grant) for Opening Day, Mickey Welch pitched the home side to a 7-5 victory over Boston. But much to Day’s chagrin, his pet club underperformed, posting a sixth-place (46-50) finish in NL standings. The individual matchup between Keefe and Welch came out much the same, with Mickey’s stats, 25-23, with a 2.73 ERA and 144 strikeouts in 426 innings pitched, no way comparable to those of his old Troy comrade. The next season was more of the same – at least as far as the co-owned New York clubs went. With Keefe (37-17) and Jack Lynch (37-15) splitting hurling duties evenly, the 75-32 Mets captured the AA pennant handily. Meanwhile, the Gothams’ improved 62-50 log was good for no better than fourth place in the senior circuit. But the imbalance in Mets-Gothams fortunes could no longer be attributed to Mickey Welch. Like Tim Keefe, he was entering the prime of his major-league career. For the 1884 season, he arguably outperformed Keefe, going 39-21, with a 2.50 ERA and 345 strikeouts in 557 1/3 innings pitched. In the process, he set a long-overlooked NL record that stood for nearly a century. On August 28, Welch began a game against Cleveland by striking out the first nine batters who faced him.8 But Welch’s standout individual performance did not lessen John B. Day’s unhappiness about the Gothams mediocre standing in the NL, and drastic measures were about to be taken.

During the off-season, Day reassigned Mets manager Mutrie to the Gothams. Then, via some artful rule-bending, Tim Keefe and star third baseman Dude Esterbrook were transferred to the Gothams, as well.9 With Cooperstown-bound John Montgomery Ward and Jim O’Rourke also in the New York lineup, the club was now the powerhouse Day desired.

The 1885 campaign found Mickey Welch at the zenith of his career. Sharing pitching duties with Keefe, Mickey went a franchise record-setting 44-11, with a 1.66 ERA and 258 strikeouts in 492 innings pitched, a performance punctuated by a 17-consecutive-game winning streak. Nor was Keefe a slouch that season, going 32-13, with a 1.58 ERA and 227 strikeouts in 400 innings. Both hurlers had successfully adapted to the rule changes of the mid-1880s (regarding balls and strikes; the lengthening of the pitching distance; the sanction of overhand pitching; etc.) by throwing from varying arm angles and adding put-away pitches to their repertoires: for Welch, the in-shoot (screwball), and for Keefe, the changeup. The two were also dead-earnest workers in the box, with a distinct aversion to losing.

But away from the field, Welch and Keefe were polar opposites. Keefe was a quiet, serious man, reserved, almost aloof in manner, and he sported the handlebar mustache near-ubiquitous among the ballplayers of the 1880s. In contrast, the clean-shaven Welch was a fun-lover. Although he reputedly refrained from tobacco, swearing, and hard liquor, Mickey was a fabled beer drinker, given to composing impromptu ditties about his favorite beverage.10 He also frequently entertained teammates, companions, and other bar-goers with a fine Irish tenor singing voice. Notwithstanding their divergent personalities (and later differences over the Players League), Mickey Welch and Tim Keefe were good teammates and maintained a lifelong friendship.

For the 1885 campaign, the New York team performed up to expectations. But an exceptional 85-27 record was good for only second place that season, as the Chicago White Stockings, with Cap Anson, King Kelly, and John Clarkson at their playing peak, came in two games better in final NL standings. During the season, the New York team acquired the nickname that would accompany the club to later baseball glory: “Giants.”11 Star pitcher Welch also received an enduring sobriquet: “Smiling Mickey,” a tribute to his even-temperedness in the pitching box – he never argued a call and was said to be the favorite pitcher of NL umpires – and the bemused grin that seemed plastered on his face.12

With an ever-growing family to support, Welch held out briefly during the offseason of 1885-1886, but club owner Day refused to yield to his “exorbitant” demands.13 Welch later signed quietly, probably for about $3,000. He pitched well during the 1886 and 1887 seasons, but a nagging back and occasional arm miseries reduced his numbers: 33-22 in 500 innings pitched (1886), and 22-15 in 346 innings (1887). Meanwhile, Tim Keefe had gone a combined 75-39 in over 1,000 innings pitched and had assumed the mantle of staff ace.

Following two also-ran finishes, the 84-47 Giants surged to the 1888 NL pennant, a full nine games ahead of second-place Chicago. Welch (26-19) ably seconded Keefe (35-12) during the season, and again assumed a support role when the Giants faced the AA champion St. Louis Browns in the post-season precursor of the modern World Series. With Keefe (4-0) going undefeated and Welch and right-hander Cannonball Crane splitting their four decisions, the Giants prevailed in the 10-game series, 6-4, and took home their first baseball championship.

The 1889 season was a virtual repeat. New York (83-43) nipped the Boston Beaneaters (83-45) at the wire for the NL crown and then bested the AA Brooklyn Bridegrooms in the postseason. Although troubled by back problems, a thumb injury, and illness in the family, Welch pitched capably for the champions, going 27-12 in 375 innings pitched. But he was ineffective during the Series, being shelled by the Bridegrooms in his only outing. Keefe also went winless, being hit hard in his two post-season starts. Only unexpected pitching heroics by Crane (4-1) and Hank O’Day (2-0) allowed New York to prevail, 6-3.

While 1889 had seen the Giants successfully defend their world champions’ crown, the season had been conducted amidst rising owner-player tension, with long-standing player resentment of the reserve clause in the standard major-league contract exacerbated by newly-adopted limitations on player salaries. Notwithstanding the fact that John B. Day was well-liked by his players, the New York Giants were the springboard of the coming insurrection, with union visionary John Montgomery Ward busily organizing a new, player-controlled major-league circuit for the 1890 season.

Although Welch had been a member of the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players since its founding in 1885,14 he did not join the exodus of Giants headed for the new league. Club owner Day, intent on holding onto at least a few members of his championship nine, tendered Welch a guaranteed, three-year contract at $4,000 per season, a pact which the Players League declined to match. Welch explained his decision to reject a lesser offer from the PL bluntly: “I am in the business for dollars and cents, and as the offer made by the old League was the better one, I accepted it.”15 Days later, he resigned from the Brotherhood.

In the end, only Welch and outfielder Mike Tiernan remained with the NL (Real) Giants. The rest joined Buck Ewing and the PL (Big) Giants. Fortified by an infusion of playing talent purchased from the defunct Indianapolis Hoosiers – Amos Rusie, Jack Glasscock, Jerry Denny, and others – the Real Giants fared better than expected on the field. The club’s pitching mainstay was the 19-year-old Rusie, who went 29-34, with 341 strikeouts (and 289 walks) in 548 2/3 innings pitched. In more limited action, Welch chipped in a respectable 17-14 record, which included a 1-0 shutout of Pittsburgh on August 29. It was Welch’s 300th major league win. In keeping with the times, the accomplishment went unnoted in the press.16

All things considered, the club’s 63-68 final record was a relative triumph. But with the Big Giants playing their games next door to the Polo Grounds in newly erected Brotherhood Park, the competition for fans had been cutthroat, and both teams hemorrhaged red ink. Shortly after the financially ruinous season ended, the NL and PL Giants merged, heralding the demise of the Players League. Tim Keefe, Buck Ewing, Roger Connor, and Jim O’Rourke returned to the Giants fold for the 1891 season, but were now on the downside of storied careers.

So, too, was Mickey Welch. He appeared in only 22 games in 1891, going 5-9 with an inflated 4.28 ERA in 160 innings pitched, for a 71-61 Giants club.17 In the final year of the guaranteed contract that he had signed in 1890, Welch returned to the club for the 1892 season. But his stay was short. Inactive for the first five weeks of the campaign, Mickey was handed the ball on May 17 for a game against the Baltimore Orioles. He lasted five innings and was removed after surrendering nine runs. Shortly thereafter, the Giants released the 32-year-old Welch, bringing his major league career to an end.

In 13 seasons, Smiling Mickey Welch posted a 307-210 (.594) record, with a 2.71 career ERA. He pitched 4,802 innings, completing 525 of his 549 starts, while hurling 41 shutouts. In 4,802 innings pitched, he yielded 4,588 hits (.246 OBA), but his strikeouts (1,850) to walks (1,297) ratio was subpar. To counterbalance that, he had often helped himself with the bat. A modest .224 batting average included some pop: 121 extra-base hits, including 12 homers. Welch scored 268 runs, and drove in 202 more. He had also been an occasional position player, making 59 appearances in the outfield (albeit with a dismal .740 FA).

In all, Mickey Welch had been a ballplayer of the first rank. And he wanted to continue. Following his release by New York, Welch returned to familiar terrain, signing with the Troy Trojans, now a member of the Eastern League. In 31 EL games, he posted a 16-14 record, with a scintillating 0.87 ERA in 267 2/3 innings pitched. But with his family growing ever larger, Mickey desired to play closer to his home, in Holyoke. For 1893, he joined a local semipro club and, with hard feelings over the Players League forgotten, arranged a preseason exhibition game with the John Montgomery Ward-led New York Giants. Pitching for the first time from the newly established 60’-6” pitching distance, Welch was hammered, surrendering 11 runs before he could get out of the first inning. He then retreated to right field for the remainder of the 23-8 laugher.18 That summer, Mickey toed the slab a few more times for the Holyoke club, before hanging his spikes up for good at season’s end.19

His playing days now behind him, Welch gave his full attention to the Holyoke businesses, a hotel-saloon and a cigar shop that he had long owned an interest in. Later, he went into the milk production business with his sons.20 In time, Welch found more reliable employment as steward of the Elks Lodge in Holyoke. Always trim and in good shape, he spent off-days hiking local hills. Or swapping yarns with Dirty Jack Doyle, a 17-year major-league veteran and long-time resident of Holyoke.21 But his favorite leisure activity was taking in Boston and New York ball games, his enjoyment always enhanced on those occasions when he was seated with his old friend, Tim Keefe. One such trip, in 1912, resulted in a meeting with Giants manager John McGraw, and a new job as a night watchman at the Polo Grounds.22 For the next 20 summers, Mickey and wife Mary would be summertime residents of Manhattan.

When Yankee Stadium was put into service in 1923, Welch doubled his ballpark duties, serving as a gatekeeper and press box attendant there. The latter position was a perfect fit for a storyteller like Mickey. On slow sports news days, reporters often filled column space with Welch reminiscences about a bygone baseball era, or his unshakeable opinion that the players of his day were the equal of, if not better than, the moderns, whose bashing offensive style of play Welch disdained. Late in his life, a delightfully eccentric Mickey Welch all-time team – Jack Doyle (not Lou Gehrig or Jimmie Foxx) at first; Ed Williamson over Honus Wagner at short; and an outfield with Hugh Duffy and Willie Keeler, but no Babe Ruth – was published in the New York press.23 New York Times sportswriter John Kiernan, who often waxed nostalgic in print, described the now-elderly Welch as “hale and hearty and lively as a cricket.”24

The passage of time may have been kind to Welch, but it was less so to his contemporaries. In April 1933, Mickey was saddened by the passing of Tim Keefe. He served as a pallbearer at the Keefe funeral. But the real blow came in October 1935 when his wife, Mary Welch, died unexpectedly at their new residence in Corona (Queens), New York. With his children long out of the house, Mickey was living on his own for the first time in decades. And when Dasher Troy – whose five errors at shortstop had nearly cost Welch the 1883 season opener – died in 1938, Mickey became the final survivor of the original New York Gothams/Giants.

By now, Welch’s own days were numbered. Suffering from heart disease, he relocated to the home of grandson Bill Welch, Jr., in Nashua, New Hampshire. In late-spring 1941, Mickey was removed to New Hampshire State Hospital in Concord, where doctors discovered that his left foot had become gangrenous.25 He died there of congestive heart failure on July 30, 1941. Smiling Mickey Welch was 82. Returned to his Brooklyn birthplace for funeral services, the deceased reverted to being Michael Walsh, the name placed on his funeral card and inscribed on his gravestone. He was interred in the Walsh family plot at Calvary Cemetery in Woodside (Queens), New York.26

While Buck Ewing (1939) and Jim O’Rourke (1945) were early Hall of Fame inductees, the other early New York greats remained neglected until the mid-1960s. John Montgomery Ward and Tim Keefe received their due in 1964. And finally, in 1973, the call to Cooperstown was sounded for Mickey Welch.27 At the enshrinement ceremony, his 84-year-old daughter Julia Welch Weiss acknowledged the plaque on behalf of the family. Long after his death, and more than 80 years after his final major-league game, Smiling Mickey Welch had become a baseball immortal.

Sources

Sources for the biographical detail contained herein include the Mickey Welch file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US and New York State Census data, family tree information accessed via Ancestry.com, and certain of the newspaper articles cited below. Unless otherwise noted, statistics have been taken from Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet.

Notes

1 The 1865 New York State Census lists Bridget Welch as the mother of seven children, with Michael (age 6), Mary (4), and infant Julia residing in Brooklyn with their parents.

2 See the 1865 New York State Census. A century later, Mickey’s daughter advised the Hall of Fame that her father’s correct surname was Walsh, and that the family had never legally changed it to Welch. See May 24, 1973 letter of Julia Welch Weiss to Cliff Kachline in the Mickey Welch file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

3 According to a respected baseball historian, “he was Michael Walsh off the field for the rest of his life. His friends called him Mike.” See David L. Fleitz, The Irish in Baseball: An Early History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2009), 29. When he erected a cemetery monument in his late parents’ honor, Mickey commemorated them and other family members under the name Walsh, and he himself was later interred there as Smiling Mickey Walsh. See the posting with photo for Michael “Smiling Mickey” Welch on the Find-a-Grave website.

4 As per Baseball’s First Stars, Frederick Ivor-Campbell, Robert L. Tiemann, and Mark Rucker, eds. (Cleveland: SABR, 1996), 170. See also Rich Westcott, Winningest Pitchers: Baseball’s 300 Game Winners (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002), 20.

5 The departure of Michael Welch from the Auburn club was noted in the New York Tribune, May 9, 1878. See also, the Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Q-Z, David L. Porter, ed. (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1990), 1646, which maintains that Welch “began his pro career with Auburn in 1878,” and an undated circa 1881 New York Clipper profile of Welch putting him with the Auburn club contained in the Hall of Fame’s Welch file.

Baseball-Reference places Welch with the Pittsburg Alleghenys of the International League in 1878, with no stats provided. The only arguable Welch connection to that club found by the writer appeared in the Boston Daily Advertiser, May 6, 1878: “Welch, a young amateur belonging to the Lynn [Massachusetts] Emmets, pitched very well for the Alleghenys in place of Lafferty who is laid up with rheumatism.” Whether this Welch was our subject or someone else, he lost to the Live Oak club, 10-1, although only three of the runs surrendered were earned. That our Mickey Welch spent the latter part of the 1878 season playing for Holyoke was reported by the Cleveland Leader, August 2, 1878, and confirmed by various published Holyoke box scores. See e.g., the Worcester Daily Spy, August 12, 1878.

6 As per Baseball’s First Stars, 170. Baseball-Reference provides no won-loss record for Welch in 1879.

7 The Welch children were John (born c. 1880), Nora (1882), Mary (1885), William (1887), Julia (1889), Helen (1892), Lydia (c. 1893), Margaret Theresa (1895), and Mabel (c. 1897), as per the May 1973 letter of Julia Welch Weiss to Cliff Kachline, and various US Census reports.

8 Perhaps because the ninth Cleveland strikeout victim reached first base on a passed ball, the Welch record went unrecognized until after Mickey’s death in 1941. See “An Overlooked Feat,” an unidentified October 23, 1941 news item in the Mickey Welch file at the Hall of Fame. In the August 28, 1884 game, Welch struck out 14 Cleveland batters in all.

9 For more detail on the maneuvers that secured Mutrie, Keefe, and Esterbrook, see the SABR BioProject profile of John B. Day. The loss of the three gutted the pennant-winning Mets. In 1885, the club fell to seventh place in AA standings. The Mets were then sold to Staten Island entrepreneur Erasmus Wiman. Two unsuccessful seasons later, the New York Metropolitans were disbanded.

10 The most remembered of these went: “Pure elixir of malt and hops, Beats all the drugs and all the drops.”

11 Popularly attributed to Mutrie, the nickname “Giants” may actually have been coined by New York Evening World reporter P.J. Donahue. For more, see the SABR BioProject profile of James Mutrie.

12 The “Smiling Mickey” nickname is usually attributed to R.V. Munkittrick, a writer-cartoonist for the satirical magazine Puck and the New York Evening Journal.

13 As per Sporting Life, April 21, 1886. Welch had signed an improvident three-year deal in 1883, and had made only half of Tim Keefe’s $3,000 salary for the 1885 season.

14 Noel Hynd, The Giants of the Polo Grounds: The Glorious Baseball Days of the New York Giants (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 26.

15 New York Times, January 14, 1890.

16 Welch was the third major-league pitcher to record 300 wins, preceded by Pud Galvin (in late 1888) and Tim Keefe (earlier in 1890).

17 Tim Keefe went 2-5 for the 1891 Giants before being released in July. He then signed with the Philadelphia Phillies. He retired after being cut loose by the Phillies in August 1893. Keefe’s lifetime major-league record was 342-225.

18 New York Times, April 7, 1893.

19 David L. Fleitz, More Ghosts in the Gallery: Another Sixteen Little-Known Greats at Cooperstown (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2007), 148.

20 Ibid., 149.

21 Welch and Doyle enjoyed hoodwinking local reporters with an apocryphal tale about how the younger Doyle had caught Mickey’s final major-league victory in 1892. See e.g., “Doyle Caught Welch in Mickey’s Last Victory,” Holyoke (Massachusetts) Daily Transcript, August 5, 1941. In fact, Mickey’s last win was posted during the 1891 season, and he and Doyle were never members of the New York Giants at the same time.

22 McGraw had a soft spot for baseball old-timers, finding ballpark sinecures for Amos Rusie and Dan Brouthers as well.

23 Jimmy Powers, “Welch Omits Ruth in All-Time Team,” New York Sunday News, April 2, 1939.

24 New York Times, January 25, 1938.

25 As per the death certificate in the Mickey Welch file at the Giamatti Research Center.

26 A color photo of the Calvary Cemetery headstone taken by SABR’s Stew Thornley is posted on the Find-A-Grave website. Note should be taken, however, of second, erroneous Find-A-Grave posting that places the Walsh/Welch grave site in Lake Forest, California. Unhappily, this bogus California gravesite is the one listed by the Baseball-Reference entry for Mickey Welch.

27 Teammate Roger Connor had to wait until 1976 for his posthumous Hall of Fame induction.

Full Name

Michael Francis Welch

Born

July 4, 1859 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

July 30, 1941 at Concord, NH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.