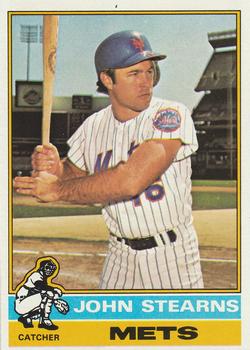

John Stearns

John Stearns was a stalwart on some of the worst New York Mets teams of the late 1970s and early 1980s. He earned the nickname Bad Dude, which he picked up while talking to a reporter in 1970.1 It stuck with him throughout his playing days. The nickname was indicative of Stearns’s toughness and confidence.

John Stearns was a stalwart on some of the worst New York Mets teams of the late 1970s and early 1980s. He earned the nickname Bad Dude, which he picked up while talking to a reporter in 1970.1 It stuck with him throughout his playing days. The nickname was indicative of Stearns’s toughness and confidence.

John Hardin Stearns was born on August 21, 1951, in Denver. His parents, Carle and Joan, encouraged him to play sports from an early age. “I grew up in a family where sports were just part of our culture,” he said.2 Carle Stearns played football at the University of Colorado (CU) and the University of Denver. He went on to a teaching career in the Denver school system, including a long tenure as coach at Denver East High School.3 John’s older brother Bill was also a pro baseball player, catching in the New York Yankees organization from 1971 through 1977, including the last four years at Class AAA. He later coached and managed in the minors. Their younger brother Rick was a linebacker for the CU Buffaloes, and their younger sister Carla was a star catcher in softball at the University of Northern Colorado.4

John Stearns graduated from Thomas Jefferson High School in Denver. He was a three-sport star, leading his football and baseball teams to state championships in 1967.5 Stearns did not start out as a catcher. “I was an all-league shortstop at high school in Denver,” he said in a 1978 interview. “During my senior year the catcher got kicked off the team, and the coach said, ‘It’s got to be you, John. You’re the best athlete on the team.”6 Stearns’s achievements in high school eventually earned him a place in the Colorado High School Athletic Association Hall of Fame.

In 1969, at the age of 17, Stearns was drafted in the 13th round by the Oakland Athletics. He did not sign with the A’s and instead attended CU on an athletic scholarship. Stearns became a two-sport star with the Buffaloes and set several university records as a safety and punter on the football team.7 Stearns made 16 interceptions in 1972, which as of 2017 was still the single-season record at the university. He caught for the baseball team. Stearns led the NCAA with 15 home runs during his senior year.8

In the 1973 NFL draft, Stearns was selected by the Buffalo Bills as a defensive back in the 17th round. In the MLB draft the same year, the Philadelphia Phillies made him the second overall pick after pitcher David Clyde. Stearns decided to pursue baseball and signed a contract with the Phillies on June 15, 1973.

The Phillies sent Stearns to the Reading Phillies of the Double-A Eastern League. He played in 67 games and his numbers were not tremendous: .241 with 3 home runs and 24 RBIs. The next season Stearns started with Rocky Mount of the high-A Carolina League. He improved significantly (.343 in 64 games) and the Phillies promoted him in midseason to Triple-A Toledo (International League), where he batted .266. For the two teams Stearns had 66 RBIs and 12 stolen bases.

The Phillies added Stearns to their major-league roster in September and he made his major-league debut on September 22, 1974, against the Montreal Expos in Montreal. He pinch-hit in the fifth inning and singled off Mike Torrez, then replaced Bob Boone as the catcher and finished the game behind the plate.

Stearns’s first hit with the Phillies turned out to be his last one. Bob Boone had become the Phillies’ everyday catcher and the team decided it did not need two young catchers on the roster. (Boone was four years older than Stearns.) On December 5, 1974, the Phillies traded Stearns with Mac Scarce and Del Unser to the New York Mets for Don Hahn, Tug McGraw, and Dave Schneck.

Stearns arrived on a Mets team that was on a downhill slide after its successes in the early 1970s, fielding mediocre teams for nearly a decade. Stearns spent his first season with the Mets, 1975, backing up catcher Jerry Grote. Stearns played in 59 games and batted .189. He continued to serve in a backup role when the 1976 season began. Stearns was unable to improve his offensive statistics and eventually was replaced by Ron Hodges. He was unhappy sitting on the bench and asked to be sent to the minors. The Mets agreed and Stearns played 102 games with Triple-A Tidewater (Norfolk)9 and batted.310 with 10 home runs, 45 RBIs, and 11 stolen bases as the starting catcher. The Mets recalled Stearns in September after Hodges struggled offensively, and Stearns replaced Hodges as Grote’s backup.

Stearns earned the starting catcher role in 1977, with Grote and Hodges as his backups. With a regular role, his offense improved. He had two four-RBI games in June, including the only grand slam of his career, against Montreal in a 6-4 Mets win on June 1. At the end of June he was batting .310 with a slugging percentage of .569. Stearns’s efforts were one of the few bright spots on a last-place Mets team. He was the lone Mets player chosen to play in the All-Star Game. (He caught in the bottom of the ninth inning.)

The second half of the 1977 season was not kind to Stearns. He batted .125 in August and.167 in September. Even with his difficulties at the plate, Stearns led the team in doubles with 25 and his 12 home runs tied him with Steve Henderson and John Milner for the team lead.

Stearns made the news that season when he laid his own “Tomahawk Chop” on the Braves’ mascot, Chief Noc-A-Homa. Stearns ran onto the field and tackled the mascot as he pranced through his pregame war dance. “I watched him for three or four years and I said, ‘Someday I’m going to clothesline this guy,’” Stearns recalled in 2010. “One day I took off, running at him like a defensive back. He looked at me like, ‘What is this guy going to do?’ I didn’t really hit him. I kind of dragged him down. It was just a fun thing but Joe Torre was our manager and he didn’t like it.”10 Torre said later that “[it] was just the Dude being the Dude.”11

Stearns’s slump continued as the 1978 season began. He hit .197 with two RBIs in April. But by May, he had turned things around. Stearns wound up having his best season offensively, setting several career marks. He finished the season with a .264 batting average, 15 home runs, and 73 RBIs, but his most notable achievement was stealing 25 bases. It broke the major-league record for stolen bases by a catcher, set in 1916 by Ray Schalk, who had 30.

The 185-pound Stearns’s hard physical play, much like a defensive back, made him a fan favorite. In the Mets’ 6-5 victory over Pittsburgh on June 30, 1978, Stearns made the final out of the game when he tagged out the much larger Dave Parker, who tried to steamroll the Mets catcher. Stearns kept his mask on during the play and held on to the ball, even though the force of the collision sent him flying. Parker suffered a broken cheekbone. When Parker returned after his jaw healed, he wore two pieces of hybrid protective gear – one that had a mask like a hockey goalie’s and another that looked like a football helmet – that helped him finish his MVP season.12

Early in the 1979 season, on April 11, Stearns triggered a bases-clearing brawl in a game against the Montreal Expos. Montreal’s Gary Carter singled in the ninth inning and tried to score when Mets pitcher Pete Falcone threw the ball into the outfield. Carter and Stearns collided at home plate as the throw arrived from the second baseman. Carter was called out but Stearns felt that he had elbowed him unnecessarily. They started trading punches and soon the two benches cleared.13 Both players were ejected.

During these years, Stearns was recognized by his teammates and opposing players for his toughness. Torre, his manager on the Mets teams of the late 1970s, said of Stearns: “He wants so bad to be so good.”14 Mets pitcher Jerry Koosman made note of Stearns’s work ethic and tenacity when he said of his batterymate, “He’s shown as much improvement as any catcher I’ve known, especially in his aggressiveness and thinking. He still tries to catch pitches in the dirt instead of blocking them.”15

Stearns played in 155 games in 1979, a career high. He struggled at the plate in the early part of the season, but rebounded in June, batting .308 with six stolen bases. He made his second All-Star Game appearance. As the Mets struggled through one of the franchise’s worst seasons (63-99), Stearns ended up playing a variety of positions. The team experimented with him at first base, third base, and in the outfield. He finished the season back behind the plate as those experiments failed to bear fruit.

After the season ended, on October 27, Stearns married his fiancée, Martha Jo, in Boulder, Colorado (home of CU). They honeymooned in Japan, where Stearns was part of a touring group of big-league all-stars.16 Marti, as she was also known, and John had a son named Justin.17

When 1980 arrived, Stearns stopped trying to be a power hitter, and his batting average rose. He batted .316 in April and .322 in May with no home runs. While the Mets continued to struggle, Stearns’s hard work led to his third All-Star Game appearance. (He replaced Johnny Bench in the fourth inning.)

Before his season ended, Stearns continued to remind fans why he had earned the moniker Bad Dude. On June 12, two drunken fans jumped onto the playing field. When they eluded security, Stearns ran from behind the plate down the third-base side of the infield. He caught up with one of the spectators, tackled him, and held him until the police arrived.18

During the late 1970s, the Mets were losing close to 100 games every year and Shea Stadium was never filled to capacity. Yet Stearns continued to play hard every day even though the fans were not there to appreciate his efforts. “I didn’t even notice the crowd. I played for the respect of my peers,” he said years after retiring. “I wanted to be one of the best players in the league and a guy who really competed. I think I accomplished that.”19

On July 4, 1980, Stearns showed why he was an outstanding defensive back in college. Expos rookie pitcher Bill Gullickson sailed a pitch over the head of Mike Jorgensen, who took umbrage at the pitch. (He had been seriously injured by a beanball while playing for the Texas Rangers.) Stearns, who wasn’t playing that day, charged out of the dugout, grabbed Gullickson from behind by the neck, and threw him to the ground. Gullickson responded by hitting Stearns with three solid punches.20

Stearns had four multi-hit games before his season abruptly came to an end on July 26 when his finger was broken by a foul tip by Dave Collins of the Cincinnati Reds. At the time he was batting .285 with 25 doubles and 45 RBIs in 91 games.

That injury was a harbinger of things to come. Stearns missed the first two weeks of the 1981 season after twisting his right ankle when he stepped on a baseball at Wrigley Field in a team workout just before Opening Day.21 When he returned, he pinch-hit and played first and third for several weeks before resuming his catching duties. He was hitting well at the time of the 1981 baseball strike that canceled most of the games in June and July. He finished the season with a .271 batting average and 12 stolen bases, but just 24 RBIs.

Stearns appeared to get his career back on track in 1982. He batted .313 in April and .337 in May while stealing seven bases. He was picked for his fourth All-Star Game, the first Mets position player to earn four All-Star selections.22 (He caught the ninth inning of the game.)

Stearns continued to hit well after the break, but was sidelined with elbow tendinitis in August. He went on the disabled list and had only three pinch-running appearances the rest of the season. Stearns still managed to finish with a career-best .293 average, and his 25 doubles tied for the team lead with Mookie Wilson.

In 1983 Stearns continued to battle injuries. He told management that he was ready to return but his elbow injury sent him to the disabled list on April 16. Stearns’s inability to throw the ball due to strained or torn muscles around his elbow kept him out of the lineup all season. The injury stemmed from damage in a game on August 12, 1982. Although he thought he was prepared to return, he still could not throw the ball. He appeared in just four games, all as a pinch-runner.

Stearns’s injuries frustrated him tremendously. He had played hard all of his life and suddenly he was unable to do that. In an article Stearns wrote for the New York Times, he described his thoughts when he first hurt his arm: “Every ballplayer has had a sore arm, and I thought that this was nothing to get upset about. By the sixth inning [of a game on July 5, 1982], I was having trouble just tossing the ball to the pitcher. I figured that a couple of days out of the lineup with some therapy and I would be just fine. I wasn’t worried.”23

After spending 1983 working with doctors, Stearns was hoping that he might make a comeback. He had two surgeries to repair his elbow, which had not healed from the injury back in July 1982, and doctors were optimistic. In the 1984 article Stearns wrote, “My life literally revolved around my arm. I became obsessed with getting it well.”24

But Stearns never regained his ability to throw hard. He played 10 games for Triple-A Tidewater in 1984, then returned to the Mets. He played in only one game in the first five months of the season. When he was finally healthy, in September, the Mets used him in parts of seven games. Stearns played in his last major-league game on the final day of the season. He had a run-scoring single off Gullickson, his fighting partner from 1980, in a 5-4 Mets loss.

The Mets released Stearns on November 3, 1984. The team had traded Hubie Brooks, Mike Fitzgerald, Herm Winningham and Floyd Youmans to the Montreal Expos for Gary Carter, who became the regular catcher. “I was kind of numb rather than angry. I couldn’t admit that it might be over.”25

Stearns said in a 2015 interview that he believed his elbow injury cut his playing career short by 10 years. “If you can’t throw, you can’t be a catcher,” he said. “I faced the Tommy John surgery thing. Even with the surgery, they said I might not play again. It was difficult for me. I was 30 years old and thought I could have played another nine, 10 years.”26

Stearns attempted a comeback in the fall of 1984 with the Puerto Rico Winter League’s Ponce Lions but he injured his elbow in the first game of the season and returned home to recuperate.27 Another comeback, with the Cincinnati Reds’ Triple-A Denver Zephyrs in 1985, was going well until he was hit by a pitch in mid-May. Stearns played in 72 games and batted .264 for the Zephyrs but the Reds never called him up to the majors. He made one final attempt at a comeback with the Texas Rangers in 1986. When the club released him at the end of spring training, Stearns retired.

Stearns did not stay away from baseball for very long. In 1986 he was named a minor-league catching instructor and scout for the Milwaukee Brewers.28 After three years with the Brewers, Stearns joined the New York Yankees in 1989 as their bullpen coach.

In 1990 Stearns was hired by the Toronto Blue Jays to manage Double-A Knoxville for 1990 and 1991. Knoxville had a 67-77 record in both seasons with Stearns at the helm.

Stearns spent 1992 as a Cincinnati Reds scout before entering the broadcast booth with ESPN in 1993. He left broadcasting after a year and returned to the Reds in 1994. He managed the rookie-level Princeton Reds in the Appalachian League. His team won the championship with a 41-25 record and Stearns was named Manager of the Year. Later that year, Stearns managed the Peoria Javelinas of the Arizona Fall League. The Javelinas won the championship and Stearns won his second minor-league championship of the year.

Stearns moved to the Baltimore Orioles organization in 1996. He worked as a scout and then as first-base coach through 1998. After two years with the Orioles, Stearns returned to the Mets. He briefly served as an advance scout before becoming bench coach for manager Bobby Valentine in 2000. After the season, he was fired but Valentine rehired him as the third-base coach when he reorganized his coaching staff.29

When the Mets made the playoffs in 2000, Stearns’s broadcasting work led him to wear a microphone during the playoffs. Mets catcher Mike Piazza struggled at the plate in September, batting just .222. In the Division Series against San Francisco, Piazza was 3-for-14. But all that changed in the first inning of the first game of the Championship Series against St. Louis. Piazza hit a run-scoring double. As he cruised into second, Stearns was heard by the millions watching the game shouting, “The monster’s out of the cage, the monster’s out of the cage.”30 Mets fans used that as a rallying cry for the rest of the series.

As a minor-league manager, Stearns tried to model his managerial style after Joe Torre. He shared the influence that Torre had on him in a 2004 interview: “He was really good at communicating with players. He was honest, laid back, and just himself.”31 Of his own philosophy of managing, he said: “I think the manager has to be a rock. He has to be the same every single day when you go in; try to bring positive energy and be the same day in and day out to everybody. I think if you are that way, a player can lean on that because he knows how the manager is going to be and he can get the best out of his ability.”32

Stearns was relieved of his coaching duties after the 2001 season. He stayed with the Mets as a scout before being hired to manage the Double-A Binghamton Mets in 2003. The team finished fifth in the Eastern League that year with a 63-78 record. The Mets were so impressed with Stearns’s coaching skills that they promoted him to Triple-A Norfolk Tides, in 2004. The Tides went 72-72 and finished third in the International League’s Southern Division.

After Stearns spent the 2005 season as a roving catching instructor for the Mets, he moved to the Washington Nationals organization. He managed Double-A Harrisburg (Eastern League) in 2006. In 2007 he managed the Triple-A Columbus Clippers (International League). He returned to Harrisburg for 2008.

After several years out of baseball, Stearns joined the Seattle Mariners as minor-league catching coordinator. It was a position that he held for the 2011 and 2012 seasons. He was also a professional scout for the team in 2012. Stearns was named the interim manager for the Triple-A Tacoma Rainiers on May 2, 2013, after manager Daren Brown was named the third-base coach for the Mariners.33 He led the team to a 76-68 record, second in the Pacific Coast League Northern Division.

Stearns was named the Mariners’ third-base coach for the 2014 season. Before spring training he had surgery to repair a hiatal hernia. When he had difficulty recovering from the surgery, he stepped down as coach. He felt it wouldn’t be fair to the team to disrupt the start of their season by forcing a change in the third-base coaching position at a later date. “It kills me because the thing we all want to do in this business is be in the big leagues. I want to come back at my age and have another shot, but I didn’t want to do it at the expense of the players and the organization. I think I can get healthy, but it’s going to be later on.”34 Seattle used Stearns as a scout when his health improved later that year.

As of 2017, Stearns has been out of baseball since 2015, although he hoped to find a team that could use his skills. “I’ve been in the game 40-some years, and that’s incredible. But the most fun is when you’re playing,” he said.35 He was spending winters at his home in West Palm Beach, Florida, but also tried to spend as much time as possible in Colorado, where his mother lived.36

Stearns died on September 15, 2022, after a battle with cancer. One of his last public appearances came on August 27, 2022, when he attended Old Timers Day at Citi Field. “No one played the game with more spirit or determination than John Stearns,” said Mets president, Sandy Alderson. “He literally willed himself to attend Old-Timers’ Day last month so he could visit friends and old teammates.”37 Former teammate and manager Joe Torre said “No one played the game harder than John. He never came to the park in a bad mood. All he wanted to do was win.”38

In a 2013 interview, Stearns said he regretted that he might be remembered as the “Bad Dude.” “I wish that name had never happened,” he said. “A writer from Sports Illustrated asked me how I wanted to be remembered at [the University of Colorado]. I think I had heard those words just a couple of times, but I said ‘bad dude.’ I regret that.”39 But it is not likely that his nickname will be forgotten.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also utilized the Baseball-Reference.com, Baseball-Almanac.com, and Retrosheet.org websites for box scores, player, team, and season pages, pitching and batting game logs, and other material pertinent to this biography.

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Chris Rainey. Rory Costello provided additional research on the family of John Stearns.

Notes

1 Kevin Kernan, “Former Mets Catcher Stearns Shedding ‘Bad’ Name,” New York Post, January 16, 2010.

2 Irv Moss, “Old Tag No Longer Fits: John Stearns,” Denver Post, July 8, 2007.

3 Terry Frei, Playing Piano in a Brothel: A Sports Journalist’s Odyssey, Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2010: 119-120.

4 Thomas Rogers, “Sports World Specials: Sister Stearns,” New York Times, August 2, 1982.

5 Irv Moss, “John Stearns Continues to Contribute in Baseball at Age 61,” Denver Post, June 9, 2013.

6 Jim Kaplan, “A Hard Catcher to Nab,” Sports Illustrated, September 25, 1978.

7 Ibid.

8 Colorado Sports Hall of Fame, coloradosports.org/index.php/who-s-in-the-hall/inductees/item/204-john-stearns, Accessed May 15, 2017.

9 Kaplan.

10 Kernan.

11 Michael Malone, “Wishing Upon a Star,” ESPN.com, January 7, 2011.

12 Mike Bass, “Dave Parker Fights Parkinson’s and Makes Peace With His Baseball Past,” Bleacher Report.com, April 1, 2014.

13 John Snyder, Mets Journal: Year by Year and Day by Day With the New York Mets Since 1962 (Cincinnati: Clerissy Press, 2011), 124.

14 Howard Bloom, “Torre So Much More Than a Player and Manager,” Sports Business News.com, August 23, 2014.

15 Kaplan.

16 Milton Richman, “Yankees’ Dent Would Like to Play Nall for Angels,” United Press International, October 24, 1979.

17 John Stearns, “The Long Comeback of John Stearns,” New York Times, September 16, 1984.

18 “Remembering Mets History: (1978) John Stearns Sets NL Stolen Base Record For Catchers,” Centerfield Maz.com, September 16, 2016.

19 Joe McDonald, “The MOFO Sports Interview: John Stearns,” NY Sports Today.com, August 1, 2004.

20 Ibid.

21 Ed Leyro, “M.U.M.’s the Word (Most Underrated Mets): John Stearns,” Studious Metsimus Blogspot.com, February 7, 2011.

22 Ibid.

23 Stearns, “The Long Comeback of John Stearns.”

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Irv Moss, “Colorado Classics: John Stearns, Former Major-League Player and Coach, Denver Post, June 10, 2015.

27 “Stearns Reinjures Elbow,” New York Times, November 14, 1984.

28 “Brewers Hire Stearns,” New York Times, November 15, 1986.

29 “Stearns to Return as a Mets Coach,” New York Times, December 17, 2000.

30 Tracy Ringolsby, “Piazza Powers Mets,” Cincinnati Post, October 12, 2000.

31 McDonald.

32 Ibid.

33 “Mariners Add Brown to Coaching Staff,” Skagit Valley (Washington) Herald, May 2, 2013.

34 Greg Johns, “Citing Recovery, Stearns Resigns as Third-Base Coach,” MLB.com, March 7, 2014.

35 Moss, “Colorado Classics.”

36 Irv Moss, “John Stearns Continues to Contribute.”

37 (Associated Press), “John Stearns, Feisty Met Catcher for a Decade, Is Dead at 71,” New York Times, September 16, 2022.

38 Anthony DiComo, “Former Mets catcher John Stearns passes away at 71,” MLB.com, September 16, 2022 https://www.mlb.com/news/john-stearns-passes-away

39 Ibid.

Full Name

John Hardin Stearns

Born

August 21, 1951 at Denver, CO (USA)

Died

September 15, 2022 at Denver, CO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.