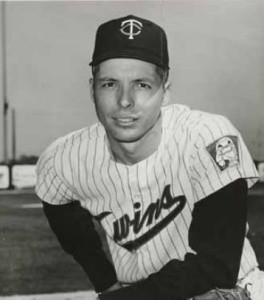

Jimmie Hall

It’s an old story. A player comes on the scene, dazzles in his rookie year, and is gone seemingly as fast as he came. Then there’s Jimmie Hall.

It’s an old story. A player comes on the scene, dazzles in his rookie year, and is gone seemingly as fast as he came. Then there’s Jimmie Hall.

Hall burst on the scene with a bang with the Minnesota Twins in 1963. Actually, he had 33 of them, which broke Ted Williams’s AL record for home runs by a first-year player who had never batted in his rookie year. Yes, THAT Ted Williams! But after five seasons that ranged from respectable to excellent, Hall hit seven home runs in his last three campaigns, and then disappeared from the game.

Hall was born on March 17, 1938, in Mount Holly, North Carolina to James R. and Velma (Williamson) Hall. He was one of 11 children, three of whom died in childhood. His father was a farmer and his mother a housekeeper.

As a youngster Hall batted .564 in his senior year at Belmont High School in Belmont, North Carolina. His father advised him not to imitate anyone else’s batting style but to develop his own. James (Jimmie’s legal name is Jimmie, not James Jr.) also persuaded his son to stay with baseball instead of working in a cotton mill.

“In my last year of high school, I wanted to go work in the cotton mill or a service station,” said Hall. “I wanted to make money to buy a car like most kids. But dad wanted me to play [American] Legion ball.”1

That extra playing time led to a minor bidding war among the Cleveland Indians, Pittsburgh Pirates, New York Yankees, Chicago Cubs, Baltimore Orioles, and Washington Senators. Senators scout Chick Suggs signed Hall for $4,000 in 1956, although the club was much more impressed with his hitting capabilities than his fielding.

“The only thing they liked about him was that whiplash batting stroke he could generate with his skinny 175 pounds,” wrote Shirley Povich. “He butchered every infield job they tried him at.”2

The 18-year-old Hall began a long, circuitous journey to the majors that was interrupted by injury, illness, and military service. His first stop was with the Superior Senators of the Class D Nebraska State League as a second baseman. He showed some of the batting stroke that he displayed more consistently later on, hitting .385 with 15 home runs in only 226 at-bats.

Those numbers impressed the Senators enough for them to bump Hall up two levels to Class B for 1957 with the Kinston Eagles of the Carolina League, which moved to Wilson, North Carolina, early in the season and were renamed the Tobs.3 By Hall’s own admission, that move proved a bit hasty as his offensive numbers showed he wasn’t ready to face the pitching at that level. In 128 games he batted only .233 and hit just six home runs in 404 at-bats. He also was adjusting to a new position. He was originally signed as a second baseman, but because Wilson was short on outfielders, Hall volunteered to go out there so he could get some playing time.

“I was a year out of high school. The [Washington] Senators were hard up for players, and they sent me here,” said Hall when visiting Wilson in 2005. “The Carolina League was good baseball. I was so overmatched. I was fighting for my life all summer.”4

Although he was “overmatched,” as he put it, Hall began the 1958 season with a promotion to the Charlotte Hornets of the Class A South Atlantic League. He played in only nine games there before he required a tonsillectomy. After he recovered the Senators sent him to the Fox City Foxes of the Class B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa (Three-I) League. He was better equipped to handle Class B pitching this time, as his average rose to .267 with 15 home runs and 38 RBIs in only 255 at-bats.

Despite the limited playing time in Class A, Hall choo-chooed off to the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Double-A Southern Association in 1959, where he played in 133 games, 78 of them at shortstop. He also spent some time at second base and the outfield. At the plate he complemented a .245 batting average with 11 home runs and 57 RBIs. In 1960, Hall played for the Charleston Senators of the Triple-A International League. His numbers weren’t overly impressive there either: a .227 average, 9 home runs and 30 RBIs in 336 at-bats.

Hall also married his wife, Judy, in 1960. They went on to have two daughters, Donna and Kimberly, and two sons, Michael and Jeffrey.

None of Hall’s totals left the Twins thinking they had a budding star on their hands. Uncle Sam didn’t help his case either. In 1961 Hall missed some time due to a hernia operation, after which he did a six-month hitch with the Army, followed by a 10-month stretch as a grunt in 1962. For the two seasons combined (1961 with the International League’s Toronto Maple Leafs and Syracuse Chiefs and 1962 with the Triple-A Pacific Coast League’s Vancouver Mounties) he had 141 at-bats in 54 games, and batted .234 with three home runs. These numbers were hardly a harbinger for what happened next.

The Minnesota Twins were a team on the rise in 1963. After they went 70-90 in 1961, manager Sam Mele guided them to a 91-71 record in 1962, just five games behind the World Series champion New York Yankees. They were loaded with young, quality players like Jim Kaat, Harmon Killebrew, and Zoilo Versalles. In fact, the 1962 squad was the youngest team in the American League.

Hall faced a rather daunting challenge when he went to the Twins’ 1963 spring-training camp. To get a job on the major-league roster, he would have to crack a well-established outfield that had great numbers in 1962. It included Killebrew (an All-Star who had led the league with 48 home runs and 126 RBIs in 1962), Lenny Green (.271 batting average, 14 home runs, and 63 runs batted in), and Bob Allison (who had hit .266 with 29 home runs and 102 RBIs).

“And I read a lot during the winter about Tony Oliva, too,” said Hall.5 “I knew it was going to be tough to stick with the club. But I figured it was now or never.”6

Two things went Hall’s way that spring training. First, he did all he could do, which was hit .293 in 22 exhibition games. Then he got a lucky wrench, er, break, when Killebrew wrenched his left knee, which allowed Hall to make the team, but even then that was a last-minute decision on the part of the Twins. They offered him a contract for the major-league minimum of $6,000 at 11:00 P.M. on the last day of spring-training cuts, just an hour before rosters had to be finalized. He started the season well, hitting a double and triple with four runs scored in seven plate appearances in his first start, an 11-10 win over Los Angeles on April 16. By mid-May, however, Hall was hitting only .167 and Mele soon relegated him to the bench.

That may have been the best thing for Hall, because he started showing signs of improvement when he got the opportunity. He hit his first major-league home run on May 19 in Cleveland. On May 24 his walk-off home run against the Chicago White Sox gave the Twins an 8-6 victory and kept alive a winning streak that eventually reached 10 games. These feats were just a tuneup for the hot streak that began June 1. Between that date and July 15, Hall batted .303 with 8 doubles, 3 triples, 10 homers, and 25 RBIs. As if they needed it, the Twins suddenly had another power bat in their lineup.

The streak continued throughout the summer. Hall hit five homers between June 30 and July 4. He homered in four consecutive games starting July 31 in games against the Red Sox and Kansas City Athletics. He hit 13 dingers in the month of August. All of a sudden he was a home-run hitter. No one was more confounded by the turn of events than Hall himself.

“I feel stronger in the majors,” he said. “I’ve surprised myself. I hit only three in Vancouver in 1962 and all were to dead left field.”7

A lot of that improvement could be attributed to the time Hall spent in the Florida Instructional League the previous winter. Del Wilber, who was Hall’s manager in Charleston, managed the Twins’ club in the FIL and spent a lot of time working with Hall. The result was a hitter who learned to spray the ball to all fields, and with power. His final totals were a .260 batting average with 33 home runs and 80 RBIs and a third-place finish in Rookie of the Year voting, behind Gary Peters and Pete Ward, both of the White Sox.

The Twins had a down year in 1964. After two consecutive 91-win seasons, they went 79-83, tied for sixth with Cleveland. No one could blame Hall for the team’s decline, as his average shot up to .282, with 25 home runs and 75 RBIs. He played in his first All-Star Game, at Shea Stadium in New York; he didn’t bat, but replaced Mickey Mantle in center field in the bottom of the ninth of a 7-4 National League win.

The All-Star Game was just about the only action Hall saw in early July, as he was benched for the first two weeks of the month after a poor performance at the plate in June. The slump came after he was hit in the cheek by a pitch from Bo Belinsky of the California Angels on May 27. He was out for only a week, but he lost weight and strength during that time and was slow in getting his timing back. The rest did Hall good, for he soon embarked on a 15-game hitting streak that lifted his average 28 points.

Before the beaning Hall reached a milestone when he hit the major leagues’ 75,000th home run since 1900, a solo shot in the second game of a May 3 doubleheader at Kansas City that the Twins lost 8-7.

After the disappointing 1964 season, Twins owner/general manager Calvin Griffith attended the winter meetings intent on making a big trade. And after two days of negotiations he almost made a blockbuster deal with Mets general manager George Weiss – Hall, catcher Earl Battey, pitcher Jim Perry, and either second baseman Bernie Allen or third baseman Rich Rollins in exchange for second baseman Ron Hunt (an All-Star in 1964), catcher Chris Cannizzaro and pitcher Alvin Jackson. Fortunately for the Twins, Weiss ended up nixing the trade. Minnesota went on to win the American League pennant and Griffith was pleased that the Mets deal, as well as another one with the Athletics, had fallen through.

“I can’t trade Hall now,” he said. “We might get something to help us but it would sure hurt us to give him up.”8

It turned out to be a career year for Hall; although his home-run total dipped to 20, he set career highs in hits (149), RBIs (86), and stolen bases (14). He played in the 1965 All-Star Game in front of the hometown fans in Bloomington, Minnesota, going 0-for-2 with a walk and a run scored as the American League lost again to the National League, 6-5.

But for all of Griffith’s praise and Hall’s career-high numbers, he was primarily a spectator as the Twins reached the World Series. Hall, a left-handed hitter, could not hit left-handed pitching very well (only four of his 121 career home runs came against left-handers), and Mele felt that he would struggle against Dodger left-handers Sandy Koufax and Claude Osteen. Hall appeared in only two games and had one single in seven at-bats with five strikeouts as the Twins lost to the Dodgers in seven games.

The 1966 Twins got off to a rough start and were 38-43 at the halfway point in the season. Mele began platooning Hall in June. He finished the season, and his career with the Twins as it turned out, with a .239 batting average, 20 home runs, and only 47 RBIs.

In December 1966 Griffith pulled off the big trade that he didn’t make prior to the 1965 season, sending Hall, pitcher Pete Cimino, and first baseman Don Mincher to the California Angels for 1964 Cy Young Award winner Dean Chance and infielder Jackie Hernandez. Hall’s average improved slightly to .249 in California, but with only 16 home runs and 55 RBIs.

While Hall’s numbers diminished in 1966 and 1967, they hit rock bottom in the last three years of his career. From 1968 to 1970 he played for the Angels, Indians, Yankees, Cubs, and Braves, hitting a total of seven home runs as a part-time player, with 69 RBIs. The Atlanta Braves released him after the 1970 season. He signed on with the Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League for 1971 but was released in June after appearing in 21 games with no home runs and only five RBIs.

The cause of Hall’s precipitous decline is a mystery. Sportswriter Jim Murray speculated that he never fully recovered from the beaning he suffered in 1964.

“Some lefthanders got the idea Jimmie may have developed an instinct for survival in the rest of his anatomy, too [in addition to his right cheek, which he protected at the plate with an earflap before they were common],” wrote Murray, “and from that day they tend to try a route to the catcher with a curveball that will orbit his right ear on the way.”9

That explanation isn’t likely, as Hall was an All-Star in both 1964 and 1965, and he was still reaching double figures in home runs as late as 1967.

Another possibility mentioned in the BR Bullpen section about Hall in baseball-reference.com was that he, like all other hitters, was victimized by the increasing domination of pitchers in the late 1960s.10 That is doubtful because Hall’s statistics didn’t improve even after the pitching mound was lowered from 15 inches to 10 inches in 1969, when Hall was still young enough at 31 to produce solid numbers.

Little is known about Hall’s life after his baseball career ended. He returned to Elm City, North Carolina, and made his living as both a woodworker and long-haul truck driver. When he wasn’t working, he was an outdoorsman who liked to hunt and fish. He also enjoyed spending time with his children and grandchildren.

Hall stayed away from the game entirely, even refusing to return to Minneapolis in 2005 for a 40th-anniversary reunion of the 1965 team. When he heard that Hall wasn’t attending the reunion, former teammate Jim Kaat responded with a remark that perhaps gave insight into why Hall never reached his full potential as a player.

“That sounds like Jimmie,” Kaat said. “He was so talented, but the glass always seemed to be half empty for him.”11

Sources

Ancestry.com

St. Petersburg Times

The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois)

Baseball-reference.com

The Sporting News

Urbandictionary.com

Sports Illustrated

Florence (Alabama) Times

Milwaukee Sentinel

Cooloftheevening.com

Notes

1 “Jimmie’s Dad, Red-Hot Fan, Gave Son Sound Batting Tip,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1963.

2 Shirley Povich, “Twins Hope Jimmie Hallmark of Victory,” St. Petersburg Times, March 19, 1964.

3 Tobs is short for tobacco.

4 Patrick Reusse, “Keeping his distance; Jimmie Hall was a sweet-swinging outfielder, one of the Twins’ early heroes. But he won’t be back for a reunion of the 1965 American League champs,” Minneapolis Star-Tribune, July 17, 2005.

5 Tony Oliva was a hot prospect who went on to a 15-year career with the Twins that included eight All-Star selections.

6 Arno Goethel, “Wasp-Waisted Frosh Hall Ads Big Stinger to Twins’ RBI Punch,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1963.

7 Goethel, “Quiet Rookie Hall Carries Cannon to Plate,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1963.

8 Murray Chass, “Twins’ Jimmie Hall Is On Real Slugging Binge,” Florence (Alabama) Times, July 7, 1965.

9 Jim Murray, “Angels Hope Jimmie Hall Bounces Back,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 23, 1967.

10 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Jimmie_Hall.

11 Reusse.

Full Name

Jimmie Randolph Hall

Born

March 17, 1938 at Mount Holly, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.